What is there left to say about The Fall? Even as a life-long fan and critic, it’s often impossible not to yield the usual tropes: references to Wyndham Lewis, Arthur Machen, the phrase repetition, repetition, repetition, and a threadbare observation of Mark E. Smith’s surly temperament. As with most clichés, there is some truth buried within them. In a post-truth, neo-liberal landscape, excavating the familiar can actually be a source of comfort. In a world where information is bias and inflammatory, having these firm foundations of criticisms in place when discussing a group like The Fall, allow us to access the work’s genuine impact and contemporary cultural relevance.

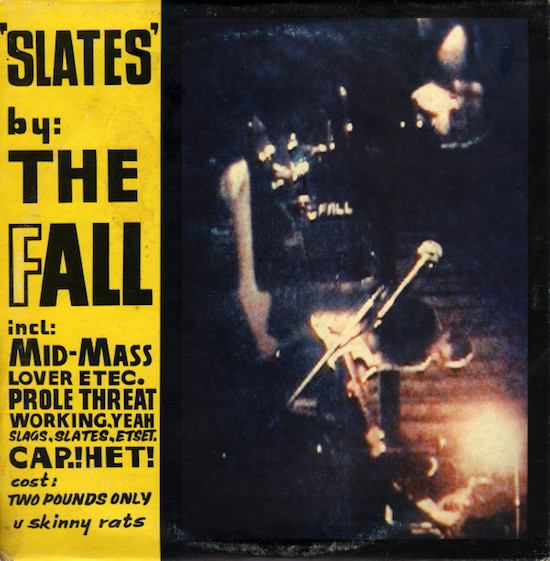

Discussing The Fall’s music retrospectively feels counterintuitive because they were so forward thinking. But if we revisit their 1981 EP (or album, depending on your stance), Slates, it becomes very transparent that it was a significant moment in The Fall’s trajectory. Along with their 1980 LP Grotesque (After the Gramme), this is when The Fall became a fully formed artistic vision with its own nuances, characters, worlds and uniquely Lancastrian insights.

Any quick YouTube search of Nick Cave and Mark E. Smith will lead you to a video of them being overtly complimentary towards each other’s work as they stumble over their amphetamine-laced words. As we know, Smith wasn’t exactly the effusive type, so what can we can decipher from this conversation? The Fall wanted to match primal music with a literary frontman. It’s the collision of these two worlds – the animal and the intellectual – that makes Slates such an effectual body of work. Both the music and the lyrical content on Slates derives from working-class auto didacticism, which is self-acknowledged and proud. Smith proclaims that he is a Prole Art Threat, whilst discrediting with contempt the poised pretentiousness of his contemporaries.

Full bias content guaranteed

Plagiarism infests the land

Academic thingys ream off names of

Books and band

Here we see Smith being conscious of his band’s own indelible formula. Plagiarism was famously a concern for him. For better or worse, his music continues to inform contemporary guitar music now more than ever. Indeed, he isn’t around to destroy their confidence with an astutely backhanded remark, which might explain the sudden surge of so-called imitators.

What The Fall did with Slates – and also around the time of Hex Enduction Hour and Grotesque – was coalesce high literary modernism with the supposed low culture of Lovecraftian pulp weirdness, filtered through the lens of half-supped pints of Joseph Holts bitter.

Mark Fisher explores this in his essay ‘Memorex For The Kraken: The Fall’s Pulp Modernism’. Here, Fisher discusses Smith’s postmodernist bent, in particular his propensity for melding intellectual influences with commonplace rhetoric and banal observations, inverting what is culturally valued – in a sense making the low (Coronation Street, working men’s club comedians, dock yard banter) respected and the pseudo-intellectual forms of authority (showbiz whines, music teachers, “academic thingys”) ridiculed. Smith created a form of anti-intellectual intellectualism by not shying away from his literary influences, but not overstating them either. In a weird way, he seemed simultaneously ashamed but proud of being well read. He was bookish without being erudite.

Slates was a crucial turning point because it defies working class stereotypes, specifically in relation to art. The Fall’s lyrics aren’t restricted to the usual kitchen sink realism in the vein of ‘That’s Entertainment’ by The Jam. Rather than having a “woe is me” perspective on life, Smith liberates himself using working class intellectualism to reclaim art as a thing for the people, not academics. This teaches us a vital life-lesson: you don’t need to be privileged to be cultured. You can be into Ezra Pound and Philip K. Dick but also get shit-faced and neck a couple of double dippers on match-day afternoon. He created work that matches the smart intensity of his literary influences, but it’s still firmly grounded in Prestwich.

It’s important to note that Mark E. Smith’s virtuosic eye for making the ordinary weird isn’t an anomaly. Look at the Russian formalists’ work on estrangement for evidence of a literary tradition of this: the term defamiliarization was first coined in 1917 by Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky in his essay ‘Art, As Device’. French Cuban novelist and master of erotica Anaïs Nin summarises it with typical astuteness in her 1968 book The Novel Of The Future:

“It is the function of art to renew our perception. What we are familiar with we cease to see. The writer shakes up the familiar scene, and as if by magic, we see a new meaning in it.”

Slates is littered with examples of this. Smith utilises everyday commonplace things and elevates the language by altering the syntax. By putting a poetic stamp on the ordinary form, he estranges us from our own concepts of the everyday and makes them uncanny and, essentially, unfamiliar:

Starring ‘gent’ and ‘man’ in Asda mix-up

Spy thriller

The quality of Smith’s estrangement places him in a canon with other great proprietors of the literary and artistic technique such as Bertolt Brecht, Jean-Luc Godard, Yvonne Rainer and Laurie Anderson. Smith, however, was the first person to mix it with a primal musical energy, a combination that is colossally influential to this day. The legacy of which can be seen in bands such as Black Country, New Road and Dry Cleaning. The way contemporary post punk estranges the everyday illuminates the absurdity of the world around us.

It’s no surprise that the restrictiveness of highbrow modernism facilitated a renewed perspective on the way in which we grasp and create art. Now, artists feel even more compelled to incorporate disparate aspects of high and low art to make new things. Black Country, New Road assimilate high culture using musicality – jazz and classical music – and integrate it with lowbrow celebrity rolling news culture: "Leave Kanye out of this!”

Because of this you can spot the economic trend of the end of late stage capitalism: what felt distinctly Prestwich in the 1970s is now a shared experience. The rapid acceleration of late stage capitalism and neoliberal economics have forced the middle class to share many of the same concerns as the working class, perhaps denoting further evidence of the growing economic gap between the 1% and us.

40 years on, Slates is still remarkably pertinent. For something that was, according to Mark E. Smith himself, aimed at people who didn’t buy records, it has a lot to answer for. You could view the EP’s permanence as a negative – after all, guitar music hasn’t changed that much in 40 years – but you could also marvel at just how progressive and fantastically strange it was in 1981. Most of the output from this particular Fall era continues to be profoundly culturally relevant to this day, but Slates is the one that changed everything.