“Scratch the surface of English suburbia and you’ll see a bored bloke looking back at you and asking what you’re up to. We’re not talking David Lynch here, it’s not as lurid as that. But that makes it all the more interesting. Like, why is that person peering out of his window so early in the morning anyway?”

Mark E. Smith, Renegade

In suburban folklore, the curtain twitcher is a key figure. What does that say about the aspirational dream of the suburbs, once so coveted by the middle and upwardly mobile working class? Can that desire be satisfied or is paranoia all that’s left outside of the busy work of hedge trimming? Is this the prize in wait?

A nagging tune in the back of your head: “I just got to heaven and I can’t sit down…” not an overwhelming eagerness, but a restless unease.

The suburban dream was unlikely to impress The Fall’s Mark E. Smith. For one thing, Manchester and the North West were historic exporters in town planning, and Smith did have his own rebel-strain of civic pride, which was very different to the swanky vision of Tony Wilson, which was antagonistic in his own way but ultimately compatible with New Labour philosophies of urban renewal. Smith’s love for the dilapidated architecture of Prestwich stood in opposition to the American ideal of suburbia – with all its imported aspirations. There’s a gleeful killjoy side to his character as well; a utopia-cynic who slashed balloons with self-satisfied relish; whether it be some idealised time of yesteryear, suburban/ rural escape, or the hope of egalitarian retribution at some ever-postponed date.

In 2008, poet Paul Farley went on BBC Radio 4’s Saturday Review and chose 1982’s Hex Enduction Hour as the album of discussion. During the debate, TV and radio executive Liz Forgan gave as her rationale for disliking the album, presented the idea that it was a demonstration of The Fall’s capacity to dampen naive hope. At the time of its release, Forgan was working for the newly operative Channel 4: “In my life it was a time of unbelievable hope”, she tells the panel, “a belief that there was a new cultural dawn. We were all rushing around wagging our tails, and out comes this group who everyone in the world says is simply wonderful, and they pour buckets of audio over every single green shoot of hope, including, I think, explicitly Channel 4. So I absolutely hated them.”

Fair enough.

Suburbia dates back to the 18th century, but it grew on a mass scale in the new formations of a post-war world, going hand in hand with an acceleration in consumer culture and mass media. These zones were presented as a new mode of life that might liberate us from the fixed class positions of old. So says aspirational politics. But ideals… Well, they fall short. By design there are only so many lifeboats. We’re not all meant to make it.

Sold to us as self-contained communities, it’s no surprise that what persists is a fear of the big old world out there. After all, once you have your castle it must be fortified – a rather shaky kind of domestic nirvana. On the one hand, we should not discount the voyeurism of idle boredom, but that more conspiratorial fear is present as well. It’s a fear both of intruders and saboteur neighbours – even if the saboteur’s great crime is to not promptly remove their bins on collection day.

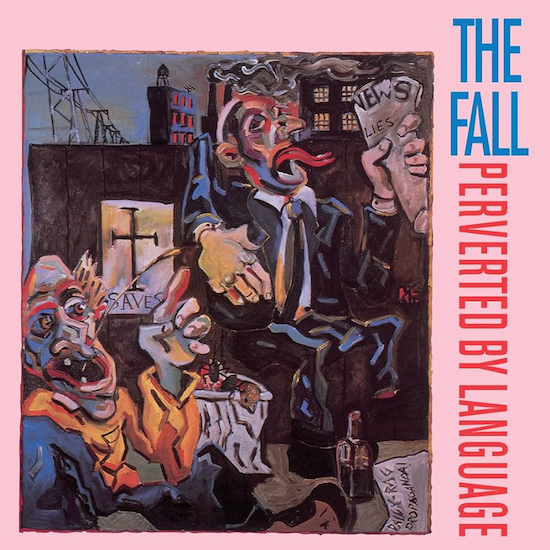

This is the space occupied by 1983’s Perverted By Language, but what separates Smith’s take on the suburbs from that of Lynch? Detectives feature in both their works, but in the case of suburbia, where Lynch sees a great mystery, for Smith it seems more of an open and shut case.

But first, some context. How were things going in camp Fall?

“A lot of stuff on Perverted By Language came out of one of those low periods that I tend to have,” says Smith in his memoir Renegade. “Kay had left and the band had changed again. That’s not to say I wasn’t excited by it.”

By 1983, The Fall were undergoing one of many upheavals. They’d lost the focus and antagonism of manager Kay Carroll, and Smith had only recently fired guitarist and keyboardist Marc Riley – critical of his playing, yes, but seemingly as a ploy to strengthen his control of the ranks.

They’d made what was widely held as a masterpiece with 1982’s Hex Enduction Hour and followed it with Room To Live that same year. Where Hex was a moment of triumph, Room To Live found the group on a much more destructive mission. Smith deployed a divide and conquer managerial ethos, not above deceit, sabotage, and the isolating of personal. Immolation and implosion, that was the aim.

But what follows a detonation?

Post punk, the movement they were nominally tied to, was faltering, more hardened experimental groups lost to a changing tide of new pop and New Romantics. In the build up to Hex, Smith had convinced himself it could well be their last record. This was obviously not to be the case, but that meant a new problem to be grappled with… What would longevity look like for a group like The Fall?

Here’s another dilemma: Kamera – the label which put out both Hex and Room To Live – had gone into administration. This meant the group had to return to Rough Trade.

As a label, Rough Trade’s independence may give the superficial impression of a shared ethos with The Fall, but there were major points of contention. Smith had little time for the didactic agitprop of groups like Scritti Politti, the communalism of squat life, or record company employees who took issue with his use of politically incorrect language.

But they had little choice in the matter.

Back they were.

We don’t like The Fall in such predicaments. Moments that call for a faltering of will, for concessions. Just think how distressing it must have been to return to Rough Trade. Not only did it represent a failure, but look at what the label had been up to in their absence. Robert Wyatt’s ‘Shipbuilding’ was put out the year prior, an anti-war song written by Elvis Costello of all people. It became a surprise hit, chiming with popular left opposition to the Falklands War. Smith at this time was having major disagreements with the socialist left. He would end his membership of the Foot-led Labour Party and even voted for Thatcher in support of her military retaliation to Argentina’s invasion. For someone of his persuasions, Rough Trade must have felt like the belly of the beast.

Perverted would be their last record for the label. But the album is a milestone for another reason: it is the first Fall LP to feature American guitarist and songwriter – later fashion retailer and presenter – Laura Elisse Salenger, known to us as Brix.

Much of the album was recorded prior to her arrival on British shores and marriage to Smith, so the jolt of her presence was yet to be felt musically. However, the album does contain one of her tunes: ‘Hotel Bloedel’. Smith’s delivery on the track is authoritative, but his words are at times uninspired – talk of “southern spectres with disease ridden, dusty, organic and psychic”, like Chat GPT turning in Fall lyrics. It’s Brix’s tune and she steals the show, her earnest melodies fighting for a place in this sound of scrapes and shudders.

In spite of her brief time in the studio, members of the group could already detect signs of an altered course. As Steve Hanley writes in his memoir The Big Midweek, upon hearing her "psychedelic inflections" on opener ‘Eat Y’Self Fitter’: “It’s clear that this LA woman, who is injecting so much enthusiasm into our miserable little band of Mancs – is going to have some sort of effect.”

Much has been made of the added pop element she brought to The Fall. In The Wire’s Fall issue, Claire Biddles writes: “The Fall had always prioritised repetition, but Brix twisted this tendency into something supernaturally bewitching, with her irresistible hooks and hypnotic playing style”, describing her guitar sound as “a stretch of satin laid across a bed of splinters.”

But these were stirrings yet to manifest. In the meantime, an unresolved matter: What’s the point of breaking something down only to rebuild to its exact specifications?

Smith knew that a change of tack was needed, discontent with inertia. You get the sense one of his biggest bugbears is people having too much time on their hands and no real plan of action, that, fundamentally, it’s bad for the soul, breeds peculiar dead end habits at best, and derangement at worst. Perhaps his focus on suburbia can be traced to the listless place he found himself. He describes his days as “walking the same places, skint”, noting how in times like these: “You see a lot more hidden sores… Your eyes have changed and the simple actions of other persons take on a significance that may or may not be there. These are extreme moments. That’s the feeling behind the album.”

Its amusing when Smith invites us to “scratch the surface of suburbia”, as that’s just the sort of language you see used to describe Lynch’s process in Blue Velvet; teeming ant kingdoms below florescent green lawns; the sense that every picket fence has its corresponding shadow; these threshold points tucked away, like the apartment of lounge singer Dorothy Vallens.

While his father is hospitalised, protagonist Jeffrey Beaumont has a lot of free time on his hands. He is a more motivated curtain twitcher, caught somewhere between peeping tom and vigilante detective. He must come to terms with those sides of his being which mirror the diabolical antagonist Frank; and in doing so might become whole.

It’s easy to see why such dynamics might haunt Lynch, a practicer of Transcendental Meditation and follower of the unified field theory, so many of his core images are notable for their stark use of counterpoint – according to the theory, once reality breaks down at a subatomic level, the two precedes oneness, the field of unity from which all reality sprouts.

On Perverted, Smith is less concerned with notions of cosmic dissolution; the themes and emotional bearings on the record are quite quotidian, even if they are explored via his oblique methods. He finds kinship with Mike Leigh, in particular 1983’s Meantime, which deals with an extended family split between the suburbs and the estates. We see the aching pain of unfulfilled lives, the steady ostracisation of ‘progress’.

The character of Mark, played by Phil Daniels, becomes a recurring type for Leigh – similar to Johnny in Naked – a bright lad with no prospects or meaningful way to fill their days. You can see his fury, the indignity of his privation; he’s made efforts to distance himself from a hooligan past but has little to show for it. Then there’s the upwardly mobile aunt Barbara, who in her habit of perfunctory busy work fits with Smith’s observation that “people started spending an unusual amount of hours meddling with their lawns and privets. Rinsing the paving and touching up the paintwork on their window frames… Killing time.”

Mark resents her, even views her as a class traitor, though it is key to point out that in spite of the comfort and abundance of her life in the suburbs, she too is discontent, her life mirroring Mark’s own aimless lack of fulfilment. Granted it’s not the same – the difference between dissatisfaction and desperation – but a symmetry nonetheless.

Smith does not approach unemployment and suburban unrest in a literal manner. These are, however, the psychic conditions that ground the album.

How to respond to such dire circumstances?

Smith may have been suspicious of hope, but he had no more time for wallowing in hopelessness. “Don’t wanna be a victim”, he sang on ‘Eat Y’Self Fitter’, his tone deranged but determined. “It’s better than Echo and the Bunnymen and all the other gonks around at the time,” he complained in Renegade, “Indulging in depression, like it’s a lifestyle choice… I hated that. I’ve always wanted The Fall to be the group that represents people who are sick of being dicked around; those that have a bit of fight in them.”

That’s the engine of The Fall. He thumbed his nose at the technocratic domination of people’s lives. To jeer in the face of futility. Pissing in the wind can evidently be a source of great amusement; still an act, a stance, a refusal to assimilate.

That spark of refusal ignites the songs on Perverted, taking the attack of early Fall to its logical extreme. These songs have a real cusp-of-oblivion nerve to them. Smith may have feared an unproductive monotony, but there’s a tension here, a home made on the precipice of laughter and mania.

‘Eat Y’self Fitter’ is maniacally insistent that yes, we are The Fall, and yes, we’re still here; nursery rhyme used as taunt, or a sibling who parrots your every word back at you. Smith uses the slogan from a range of Kellogg’s All-Bran cereal, a repurposing of the ad speak we might find in the morning paper while sat at the kitchen table. It’s made into a call and response for cackling carnivores. Gone is any sense of organic wellness.

In The Big Midweek, Hanley reveals that Smith’s instructions for the tune went so far as, “I’ve got a new song. I want der-de-der-de-de-der-de.” This shows that in a musical setting, it can be quite liberating to have an incompetent dictator. He might be telling you what to do but he doesn’t know exactly what that is. On the one hand this leaves you a lot of freedom, but never the luxury of the blank page or time to second guess. Consistent spontaneous creation is a must. You can see how, in the case of Hanley, years can pass you by on such taxing yet fulfilling demands.

‘Eat Y’Self Fitter’ is typical of Perverted in that it hinges on the work of guitarist Craig Scanlon. We still have the tag team drumming of Paul Hanley and Karl Burns, and Steve Hanley’s unmistakable anchoring bass, but it’s Scanlon that reigns supreme. He has this focus on gnawing repetition, often fixated on two or three notes at a time. He’ll needle these base elements for minutes on end, as if in search of some dour truth. Smith was critical, believing the style had run its course – “plain monotony can get fucking tedious” – but on highlights like ‘Garden’ and ‘Smile’, Scanlon reaches some sort of downer transcendence.

Smith is not alone in his hesitance toward the record. Perverted is notably absent from Mark Fisher’s much cited essay on the group’s pulp modernism. He writes that by 1983 “The Fall’s greatest work was behind them. No doubt the later albums have their merits but it is on Grotesque (1980), Slates (1981) and Hex Enduction Hour (1982) where the group reached a pitch of sustained abstract invention that they – and few others – are unlikely to surpass.”

Yet surely Perverted sustains that abstract pitcht; lyrically as cut-up as ever, musically even more insistent – and let’s not forget the astonishing singles of that time like ‘Wings’; a back alley, time travel saga on par with Philip K. Dick.

‘Tempo House’ is a blinder; an absurdist Bernard Manning set full of sputters, flem and non-sequitur punchlines. ‘Garden’, meanwhile, might be the most unfathomable thing they ever put out – heavier than those hulking dead-eyed giants ‘Winter’ and ‘The NWRA’. Just listen to the sound on ‘Garden’ – drums and dirge and little else. We’re locked in for Fall eternal, where propulsion and stasis uneasily cohabit – not unlike Tony Conrad and Faust’s Outside The Dream Syndicate. The lyrics are a maze of scenes and symbols; in a god’s domestic sanctuary is revealed a monstrous "three-legged black-grey hog", a pulpy horror novel is stacked below a tome of German history, schlocky television dance troupes share a song with biblical incantations, all intercut with this strange monologue where a Mr Reg Varney of On The Buses fame finds an explosive solution to telephone noise pollution – suburbia not the social pacifier it’s cracked up to be.

In contrast there are cuts Hanley would deride as "Fall by numbers"; ‘Neighbourhood Of Infinity’; ‘Hexen Definitive/Strife Knot’, songs that made him wonder: “Is the record-buying public’s appetite for seven-minute songs with one riff ever going to be satisfied?” Yet even these are unjustly maligned. ‘Neighbourhood’ has a real weight-and-thwack to its escalating grind, while as ‘Hexen’s title suggests, it may be an off-cut from the Hex-era, but it seems to function as a despondent eulogy of a certain Fall mode, a fitting epitaph.

Now let’s get one thing clear, despite the hesitancy of those involved, Perverted is a great album. The issue is that in the grand Fall saga, it’s a tad narratively unsatisfying. Imagine if after the demolition of Room To Live we go straight to the birdseye soar of Wonderful And Frightening opener ‘Lay of The Land’. Perverted complicates things. Indeed, the very form of the album – marathon behemoths and strange little asides, drastic fluctuations in audio quality – seems structurally resistant to canonisation.

Is it an awkward stop gap, a fruitful relapse, or a culmination? Hard to say. Then again, as Pat Nevin said on Paul and Steve Hanley’s Oh Brother podcast: “I cannot give you a graph of The Fall, it’s impossible.”

Perverted is a window into social and psychological derangement, the hysteria of a nation in limbo. The Fall might not offer us answers or happiness in return, but they’re an enlivening force. We’re more alert for our contact with The Fall, even if we can’t put into words exactly what we’re alert to.

The Fall carved a hole in the rain for us.

Right on the cusp of nihilistic withdrawal, a sudden jolt of the spark inside.