The guilt of not “getting the Fall” is the same guilt one feels after masturbating twice in one day. I mean that sincerely – you feel like you have been left out and are missing something in your life. The rabid fandom and mythologisation surrounding The Fall can be disconcerting. They are the kind of band where you could hear the ‘wrong’ album from them. An album that puts you off from investigating them any further – which for a band that are notoriously ‘difficult’ anyway, is highly likely.

When getting into The Fall, their music is a total unknown – and totally hostile. I have rarely felt more heavily attacked or defeated than when trying, and failing, to understand their music. And this was how a lot of people felt throughout the 80s – especially during their “classic” lineup which produced some of the most tormenting and uncanny guitar music ever.

The instrumentation was strange, but what really pushed The Fall into the fringes was their frontman, the late Mark E. Smith. Famously prickly, with an unmatched stage presence; he seemingly had the ability to control others at a glance. He was clean-cut, but there was something curiously diseased about him. In the beginning, you would see him a fresh-faced lad, but by the end of the 80s and beginning of the 90s he would turn up so thin, sallow and odd-looking, you would have to look twice to recognise him.

This strictly impenetrable and anti-commercial stance came to a sharp end however in 1983, with the arrival of Brix Smith. The music became more tuneful, and the band even had a sense of rockstar swagger about them – even though MES still inhabited that grey anonymously ill-intentioned look all writers have. They even produced a few moderate UK hits with covers of, ‘There’s A Ghost In My House’ and ‘Victoria’ . A change for The Fall, but certainly not a change for the worse. There is lots to be said said about the albums released during the period 1979 to 1986, but here is the crux of the matter – they are all brilliant and exemplify why they earned the label of “The Best Band In The World”.

And then came the late 80s which brought on multiple problems for the group. There were inter-band relationship problems as well as troubles in Mark and Brix’s relationship. This culminated in the release of The Frenz Experiment (1988), The Fall’s first sub-par album. Not bad, but not up to scratch with their near-perfect eight album run prior to it.

These problems came to a head in 1989 and MES found out, it’s a lot easier to start trouble than to stop it. The departure and divorce from Brix, unstable lineups and an ever increasing drink and drug problem, The Fall headed into the 90s with an uncertain future.

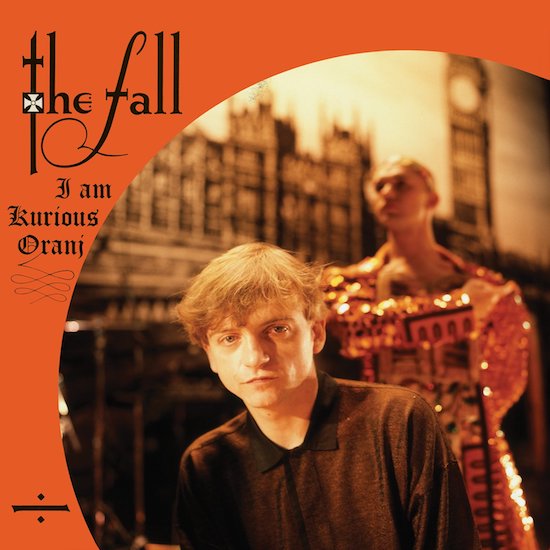

However, there was another album released in 1988. Oft overlooked, I Am Kurious Oranj is one of The Fall’s most inspired, strange and original works. What sets it apart from the rest of The Fall’s discography is that it was intended as the soundtrack for the ballet I Am Curious, Orange, a collaboration with the dancer Michael Clark, loosely based on the 300th anniversary of William Of Orange’s ascension to the English throne.

It may ‘only’ be a soundtrack to Michael Clark’s ballet, I Am Curious Orange, but it is in truth one of the most singular and packed works by The Fall. From the deconstruction of the Armagh disturbances to the pseudo-science of Jung’s “Uncollective Consciousness”, It’s MES at his most volatile and disjointed – sputtering with no inhibition.

At this time MES’ infatuation with grotesque horror (Lovecraft, Poe etc.), was largely absent from his writing. Instead, it was the English mysticism of William Blake who MES looked to. And his presence can be felt all over the album. This is most obvious in the version of the hymn, ‘Jerusalem’. Smith doesn’t simply take influence from Blake, but instead places himself as a spiritual successor to the visionary poet – almost embodying him at times. Treading in these large footprints, the songs on the album see MES treat the landscape as not just what you see but instead, an alternate reality, which if you are in the right state of mind, you can visit. Indeed, the similarities between the two aren’t reserved to their writing. MES and Blake shared a mystical character and creative process with one another. Both making great use of half or undigested knowledge – resulting in what can appear like messy writing, which then reveals itself to be filled with scrambled messages.

This technique is elevated my Mark’s drawl – the original words can be relatively unintelligible but new ones emerge (to the listener) in their place. Smith’s writing from this point onwards became increasingly unconcerned with whether the actual content of the message was received in its original form or not. But rather, a need for unscrambling messages in unique ways became the intent. This rejection of a cohesive reality in his writing laid way towards a kind of hyper-reality.

The track, ‘Kurious Oranj’ portrays this at its most extreme on the album. As he laid out in his memoir Renegade:

"We adapted the title from a Swedish porno film, I am Curious, Yellow. I was trying to make the point that we all share some kind of common knowledge that’s within ourselves; that comes out in all sorts of things. Some people call it a gene pool. It’s as if you already know subconsciously about historical incidents. You don’t have to have been taught it. It’s in-built. At the time I wanted to put this across, basically as a loose explanation of what was happening in Belfast: it’s in the head and bones and there’s nothing you can do about it."

MES may have called it the "gene pool", but his explanation lies closer to Jung’s "collective unconscious" theory. The song upon close inspection of the lyrics, is more of a satire of the idea of genetic memory, taking it to an absurd extreme. Did Orangeism pave the way to the atom bomb? Perhaps, but it would be a strange claim to make of genetic memory. It seems that the genetic memory slant is more of an excuse for free-associative ramble – with a heavy element of parody. It’s important to remember that MES was a fan of sci-fi, alternate history, and flat-out pseudo-science – he got a kick out it. It freed the imagination and opened up an alternate take on history.

This idea of alternate history continues on the track, ‘Guide Me Soft’ – a thematic song in the context of I Am Curious Orange. A simple prayer spoken by William for success in his endeavours. As MES explains, "When I was working on ‘Curious Orange’, I heard or read about the theory that William Of Orange brought Venereal Disease to England. Ridiculous of course, probably originating from mad Catholics, but it inspired me to writing a song about the question where AIDS originated from."

These strange theories and sayings pop up all over the album and are seemingly unintelligible. Evidently, the album is messy. So messy it seems purposeful. Half-ingested, disparate ideas meet in songs almost like the convergence of ley lines.

“Mark was fascinated by ley lines. He was a bit of a witch, a psychic, a warlock – he understood energy intuitively", said Brix Smith.

It was during this time that the rumour of MES being psychic began to really kick off – something that was only encouraged by his embracing and self-mythologising of it. “Mark is psychic and he knows it. He’s a precognitive psychic, able to pick up snatches of future incidents before they happen", said Brix.

So, looking at it from a new perspective, MES’ scrambled messages reveal themselves. Kurious Oranj isn’t just a soundtrack to a ballet, but instead the most personal yet far-reaching Fall album. Underneath the MacGuffin of collective unconscious lies frank discussions of MES and Brix Smith’s relationship, as well as his feelings about the Cold War. Maybe this was the most upfront MES ever was in regards to politics.

Take ‘Cab It Up’, on the surface a song about living it up in London, but with close reading of the lyrics it reveals itself. “Götterdämmerung” utters MES, which in German means, “twilight of the gods” or, Ragnarok – the end of the cycle of world history. A very MES concept no doubt, and could easily be thrown away as an ad-lib. However, using this idea of ley lines, we must take ideas from different songs and cross them to find their meaning. Atom bombs and Götterdämmerung – The Cold War, which was still very much in swing in 1988. His humour again shines through here however, as the use of Götterdämmerung again feels exaggerated to the point of parody.

On the flip side of this lies ‘Bad News Girl’ – MES’ most personal pieces ever committed to song. In the song, two unnamed characters, our narrator and the “bad news girl” are going through the process of separating. The narrator finds that via this process he is in a "troubled place" even though he is "acclimatised to [her] mind". He says that what the "bad news girl" says is true but that "jaded lust and tiresomeness" are not what he wants to look at. He is bored with her.

However, "plenty of people will keep [her] occupied" and "wet sex’ll keep [her] anaesthetised". It is OK for her to be a "hot stuff girl" but she is also "bad news" too. He’s happy to say to her, "Goodbye my dear." As Brix says in her memoir, The Rise, The Fall, And The Rise:

“I wrote one tune that started off like a slow lament and built into a fast-paced punchy song. Mark turned it into ‘Bad News Girl’. It was clearly about me; this wasn’t some kind of riddle, he was putting our problems to the forefront. I knew it. I demanded, ‘Is this song about me?’ At first he told me it was about one of Michael’s dancers, a very sweet, gentle, woman. We all loved her. We’d done a studio performance of ‘Deadbeat Descendant’ for television and she’d danced with us, in a leotard and furry boots. I was later told she was allegedly having an affair with Mark and would be taken on tour to dance with the band… Finally, Mark admitted to me that I was ‘Bad News Girl’. It was a real slap in the face. Humiliatingly, I would have to actually perform the song in the ballet on stage in Amsterdam, a five-day residency in Edinburgh and a two-week stint in London.”

A year later MES left Brix and so came the end of the golden age of The Fall. MES and whatever bunch of people he had left in toe headed into the 90s, where things only got worse. But I Am Kurious Oranj remains as one of their most defining works. A convoluted mess, impossible to pin down for more than a second. But that is what made The Fall, The Fall.

It is impossible to pin them down.