Imagine yourself in the rural Sussex of 1972; Hastings to be precise, in the house of the watercolour painter Edward Burra. You’re in the wings, witness to a televised interview in which Burra is supposed to reveal what makes his art tick. It’s noticeable that, though courteous, Burra is happy to stonewall any questions about his work and seems to positively revel in the long, uncomfortable silences that follow. Asked why he doesn’t attend the opening nights of his exhibitions, Burra replies: “No, I shan’t dream of telling you why I don’t go.” A long pause ensues, where Burra appears to have remembered something he thinks worth saying. “I never tell anybody anything. So they just make it up.” He pauses again to have a sip of something or other. “I don’t see that it matters.” The interviewer, finally sensing there is a lead after a wearying day’s worth of polite rebuttal, asks: “What does matter?” Burra snaps into life and replies, “Nothing.”

I have often thought about Burra’s public indifference to being seen as successful. His unbending work ethic was often a battle of wills with his arthritis and maybe his sexuality, but it was primarily the manifestation of his determination to do things his own way. Burra sees his conversation with the viewer as one that is in the paintings alone. Happy to tease, to plant signs to pathways where the viewer can guess meaning, Burra’s communication stops where the art ends.

To find a contrasting way of saying nothing, we transport ourselves to another Sussex, thirty years later. Where we find a young northern psychedelic rock band called British Sea Power equally determined to do things their own way. Their “wunt be druv” attitude is still a core element of their collective being: later extending to a brave and principled name change, to counter an increasingly hostile and aggrandising nativism, post-Brexit. But that story is for another time. For now, unlike like Eddie Burra, they are happy to play footsie with the media and a nascent fanbase, (both settling into a new world of internet communication), with talk of map references, wildlife – both at their own club shows and that found in nature – Soldier Svejk-style booze ups and obscure cultural histories. Unlike Burra’s, British Sea Power’s silence is there to act like an open door for a curious rock press. That’s what’s expected of it, and them. That’s still the pop music game at the dawn of the digital revolution.

How old this stuff about teasing fans and media sounds, just twenty years down the line. Looking back we see the antics of Sea Power as the first step in straddling the two worlds of contemporary pop music: the traditional – physical production and the new – digital consumption. Over the years they have often done this brilliantly, at other times uneasily and even rather clunkily. But, regardless of later work and actions, their early ideas around presenting mystery, and the accumulation of hard-to-find cultural lore as a passport to some greater feeling can feel garnered from another time. Counterintuitively, Burra’s mode of communication seems more attuned to the here and now; the “listen, but don’t reply” attitudes of the old imperial establishment mirroring our own online narcissisms.

The game leading up to Sea Power’s magnificent debut, The Decline Of British Sea Power, was a story of a splendid art being used to bolster a sad profession that stood on the threshold of impecuniary times. Powered by Rough Trade’s money and enthusiasm, (and doubtless the label’s new concerns about file sharing and CD burning), a narrative of the band was built up towards the album release. Each single boasted multiple CD and vinyl formats. By the release of the single ‘Carrion’ in late June 2003, Sea Power had released an album’s worth of non-album material. Fans had twelve original tracks to hunt down, excluding remixes and early mixes of single and album tracks. Buying the 2001 ‘Remember Me’ single, for instance, was akin to spotting every species of resident finch during nesting time. Spread over three CD and two vinyl releases, there are six b-sides to collect alongside the “standard” b-side, ‘A Lovely Day Tomorrow’ and two differently timed versions of the lead single. Falling in with this kind of activity was fun, though, and most songs on the singles were of remarkable quality and presence. ‘Albert’s Eyes’, ‘The Smallest Church In Sussex’, ‘The Spirit of St. Louis’ and ‘Salty Water’ could have easily graced The Decline.

Accompanying these releases were the demented live shows, a phenomenon that is now entrenched in the wider Sea Power myth. To the uninitiated, a Sea Power gig in 2002 and 2003 could seem like a confusing mix of spectacular eccentricity bordering on genius (or idiocy), soundtracked by a set of powerful, mysterious songs. Compared with the stoner mild and electro-boogie of many late nineties and early noughties gigs, Sea Power’s punk vaudeville was a shock. The shows also encoded a striking set of visual semantics that initially baffled, became ritualised and were inevitably codified into idiot’s shorthand by the music press. The onstage props encompassed all that was hinted at in the songs and in the press cuttings: foliage and wildlife, bacchic chaos, and nods to the brutal history of twentieth century Europe.

These happenings are all testament to Sea Power’s sense of occasion, creativity and drive. The band also knew how to play their semiotic games at arm’s length, heightening the drama. Named Yan, Hamilton, Noble and Wood; they sounded like they were guardians of a monkish secret order, living in some old forest. It certainly worked: I remember a friend, like me in his early thirties, telling me about “this amazing weird band,” whose first single he’d bought. He’d snapped it up for the incredible artwork alone; the font-based designs reminded him of New Order’s early covers. That was the bait for me, and many others, the nods to the musical glories of the early 1980s; for those who had just about missed them. It felt that new socio-cultural codes were being formed, evoking all the gloomy cod-portentousness of that previous era to shake something new awake.

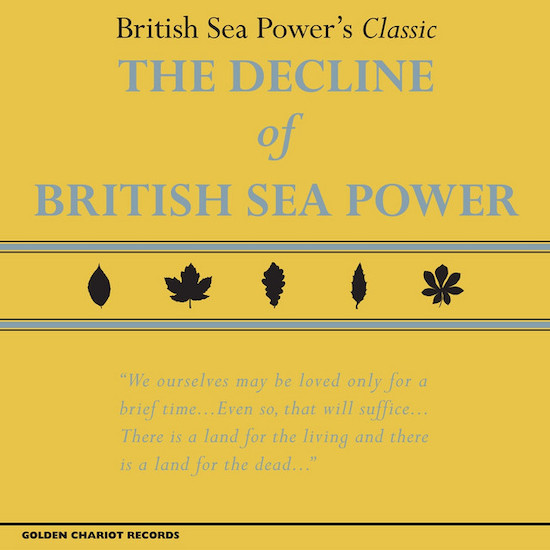

On to the record. We start, as many did back then, by pouring over an album cover that conveys considerable emotional power. It’s an extremely confident gambit to crib your own epitaph, to fuck with notions of who values your work, or time itself, and to invite all manner of criticism by stating your debut album is a classic. Especially when you’ve called your band British Sea Power. This is how you say nothing matters.

Evocations of death, unconsciousness and decay are also easily found in the song titles displayed on the reverse. Drownings, carrion, horror, loneliness, blackouts and remembrance of the dead… Burra, who often painted skeletons or ghostly figures in the landscape, would have approved of this macabre element. Yet the cover of Decline doesn’t advertise a collection of desiccated sonic grimoire obsessed with its own mortality. The primrose yellow cover is primarily about hope, new starts and life; with the beech, oak, maple, horse chestnut and elm leaves dovetailing with the hunting rifles reworked as ploughshares, symbolising Isaiah’s swords. The paraphrasing of Thornton Wilder’s lines is also uplifting – elegiac, even.

The music contained within the sleeves is the right hook to the parries performed by the cover. After the sacerdotal polyphonies of opener, ‘Men Together Today’, the brashness of ‘Apologies To Insect Life’ and ‘Favours In The Beetroot Fields’ can still jolt the senses. With their restless subject matter and hints at conquest, sex and bad trips, this pair of scrapping twins collectively sound like the scraping of fingers down the chalkboard. A track or so later the chainsaw growl of the opening riff to ‘Remember Me’ tosses off bucketloads of male energy, despite the song’s subject matter dealing with old age and infirmity. ‘Dark Ages’ boys games in ‘House Mother Normal’.

Mystery is found with three haunting and deceptively simple tracks like, ‘The Lonely’, ‘Blackout’ and ‘Something Wicked’. Collectively their gnomic lyrics and plaintive, sometimes foreboding music brings to mind Edward Burra’s incredibly unsettling work, ‘The Straw Man’ to mind. Painted in 1963, the picture shows five men silently kicking a straw man around in some unexplained ritual near a bridge. Both painting and tracks set up many cues but few explanations; emitting “the strangest” feelings and emotions, imaginings that open up further hinterlands to explore. What do they signify, these song lyrics that smuggle thought bubbles into the listener’s consciousness: of vacuum sealed jars and death’s-head hawkmoths, and Liberace serenading us from beyond the grave? To nick a line from another track, the majestic ‘The Lonely’, it all seems like another language. Here, Burra’s straw man can be us, the listener, slowly unravelling with every kick the music gives, absorbing the emotional punch with the knowledge we gain.

It’s striking just how theatrical the record feels: a theatricality that surely reaches its apogee with the last two tracks: ‘A Wooden Horse’ and the titanic ‘Lately’, which, with its loud and quiet parts, always struck me as a number that could be belted out in a West End musical. ‘Lately’ still plays out as a fabulous conceit; a lumbering behemoth that references mythical Greek heroes, putsches and George Formby; whose face stares back at us in our mind’s eye, like a grinning Brylcreemed doll. Played live, it would dissolve into the cauldron of metallic noise that was ‘Rock In A’: the band members capering about like Little Gwyon after he’d dipped his finger into the cauldron of Ceridwen. ‘A Wooden Horse’ solemnly takes up the role of epilogue; its melancholy tone set by the morse code, and piano riff mirroring the ‘London Calling’ signal.

All these psychicke games are played out on land, even if that land is sometimes the underworld. By sharp contrast, and maybe a reason for their power, two keynote tracks on Decline, ‘Fear of Drowning’ and ‘Carrion’ deal with the British coastline. The imagery invoked by them, whilst as gnomic and referential as the other tracks, somehow has a sharper focus and a slightly different, maybe more legible narrative. There’s certainly a clear destination; as both seem to want to drag us down to the ocean’s floor, whether to drown or to lie 8,000 feet below, covered in kelp, maybe waiting for your sweetheart’s call. They also possess formidable pop hooks; the gasp in ‘Fear Of Drowning’ has echoes of Lennon’s falsetto on ‘Fame’ and the ‘Carrion’ impishly rewires a Pixies track or two: stadium rock for dreamers in bedsit land.

What to think of The Decline Of British Sea Power twenty years on? It was a debut that, due to its own near-mythical qualities, immediately threatened to pin the band down like butterfly specimens on a board. I can’t think of many British rock debuts, aside from Piper At The Gates Of Dawn and Unknown Pleasures that possess the same time-bending qualities and unique character. The follow up, 2005’s beautiful Open Season, couldn’t match the sense of occasion Decline conjured up, despite it containing some of the band’s most brilliant numbers. But time catches up with all of our best plans in ways we never expect. The last twenty years have seen Sea Power navigate a rapidly changing cultural landscape, invoking public and industry bafflement and “National Treasure” status. Along the way they’ve made some brilliant, mildly disappointing, and downright odd records; continually reinventing themselves whilst carving out a clear place on the musical map. No act is quite like them. So how to reevaluate their debut right now, when all the cultural and commercial trappings that meant so much back then are compressed into digital form, and tailored for an indifferent scroll of the thumb? The Decline Of British Sea Power is still a magnificent rock record: deceptive and addictive and one that feels of no particular time. So why tell anybody anything?