It would have been at some point in late 1987, my senior year of high school, and it would have been in one of the two English literature courses I was taking that year. (Because I sure as hell didn’t want to do phys ed classes after I didn’t have to any more.) I had heard this song ‘Just Like Heaven’ on the radio and was randomly enthusing about it, because it was really good and all. I remember my classmate Susan Orozco – who regularly preferred to dress all in black, like a small coterie of people at our high school – saying in response “Yeah, but I think they sold out.” My reaction was essentially confusion – the class was about to start and I just wasn’t sure what to make of it. What was there to sell out from? And if it sounded this good, why complain?

A couple of years back I celebrated The Head On The Door’s 30th anniversary for tQ and so here I am again a couple of years later with the next album along the way. So I won’t try to add anything further to the potted band history I already gave in that feature, except to note an extension. After that album’s well-deserved success in the UK and elsewhere (especially on incipient alternative radio in the US) the temporarily stable lineup of Robert Smith, Simon Gallup, Lol Tolhurst, Porl Thompson and Boris Williams, spent 1986 dealing with retrospection colliding with the present. The Standing On The Beach singles collection – easily one of the best of its era, hands down, a perfect illustration of just how Smith and company’s pop instincts had been on since the start – served as both a good reason to hit the road some more and create a great concert film in The Cure In Orange while they were at it.

I’d heard the band once by this point – in an English class that year, someone had brought in ‘Killing An Arab’ because we’d all read The Outsider. That might have been the first time I truly got to grips with unintended consequences on an artistic level, as that year was a particularly fraught one when it came to the Reagan government and the Arab world, notably a series of clashes between US Navy forces and Gaddafi’s in and near Libya. Smith’s summation of the key incident in Albert Camus’s novel – however much said text itself was its own form of Orientalism and projection – got misread as an endorsement of such responses, leading to points of clarification, stickers on the singles compilation and so forth.

But I hadn’t really heard anything else by the band – even living where I was, near San Diego, and thus in a real hotbed of Cure fandom and alternative music in general. So when I heard it in 1987, ‘Just Like Heaven’ seemed to come almost out of nowhere. It was a strange, silvery, unusual song, with an unusual but absolutely compelling singer.

Ultimately I didn’t pursue the Cure any further than that beyond noting it away – it was just one pop breakthrough in America, and even then was low on the top 40; instead I was just starting to get to grips more with Depeche Mode and New Order among others, thanks in turn to their own higher profiles. It took ‘Fascination Street’ and Disintegration in 1989 for me to fully go “Okay… there’s really something here, something big”, and after that I haven’t stopped. I do wonder how my younger self would have reacted to Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me in 1987 if I’d taken the plunge in full then. And plunge is an appropriate world, because that’s an album to drown in.

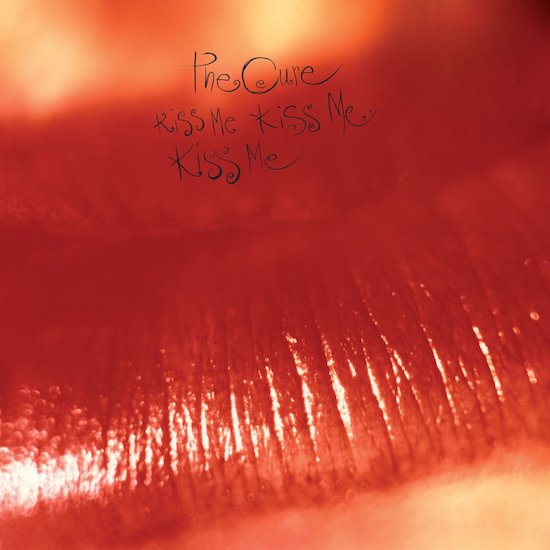

Or maybe more accurately be consumed by, thanks to the image of Smith’s lips in vivid red closeup in cover, turning what had become one of his central signifiers into an overwhelming image of moistness and skin. But having spun out a series of ‘regular’ albums for almost a decade – around forty minutes or so each, however differing the sonic approaches might be from album to album – The Cure, again assisted excellently by Head On The Door producer Dave Allen, went for it and produced a sprawling double album, not to mention a slew of B-sides on the various singles. It was a perfect complement to the similar sprawl one could find on Standing On The Beach, really, except instead of it being the chance and trace of time, it was a statement of purpose, fresh and immediate, combined with that ineluctable feeling that any artist in any field might have that they’re really on the right path, able to be uniquely themselves but increasingly being rewarded for doing exactly that. And they went for it.

Disintegration’s monumental and near monolithic chill and angst and sweep casts Kiss Me into a bit of a shadow now, perhaps more in America than elsewhere – but Disintegration was the bigger hit, fully cemented them for stadium/arena level here from that point forward, and so forth. But the band that recorded Kiss Me didn’t know about Disintegration yet, similar to the way that the band that recorded Music For The Masses didn’t know about Violator yet, but Depeche Mode ended up with the 101 film underscoring that they were well on their way, as arguably The Cure In Orange did more straightforwardly. Throughout Kiss Me, The Cure feel like they know something good’s going to happen, that the wind is clearly at their backs.

Without simply doing a track by track breakdown, noting how the first two tracks work helps clarify the album’s feeling and impact. ‘The Kiss’ opens the album and arguably sets the tone for much to come in a particular way – namely, that there’s a focus on the music first and foremost, that Smith’s own voice often comes in much later than expected, in this case more than halfway through the song. They had pursued this approach any number of times before – ‘All Cats Are Grey’ on Faith and ‘Push’ on The Head On The Door are two particular examples among many.

There’s almost a sense throughout Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me that Smith is comfortable enough to showcase the collective work of the musicians – like a handy dare to the world, saying without saying it, “Hey, check out who I’VE got working with me.” (As is well known now, Tolhurst had essentially surrendered a fully creative position in the group due to his vicious alcoholism, leaving Thompson to do the keyboard work to a large degree – but if it’s only a functional quartet, it’s still an amazingly great quartet.) Having toured regularly with that lineup for a couple of years at a time of increasingly greater attention, it underscores the sense of confidence at play.

Which, of course, is slightly ironic given what ‘The Kiss’ is about – and it’s not easy confidence. Anyone familiar with the band’s work would be forgiven for thinking they’d gone back in time a little with ‘The Kiss’ – the oppressive feeling immediately harkens back just five years to the glowering blast of Pornography. But there’s something to the build of the audio drama here that’s uniquely its own, the way it starts big and tense and slow from the rhythm section, how the twisted rising snarl of the guitar feels like something being pushed through a never-ending series of breaking points, how when Smith sings the album’s title phrase to kick off the lyric, he’s not resigned but explosive. If ‘Sinking’, the last ‘new’ song aside from a couple of B-sides that anyone had heard from the band prior to this album, had ended The Head On The Door with an elegant sway and descent, this is the same song as undead revenant back for angry, bloody revenge. In fact, this song almost defines the term ‘hate fuck’ before it was even popular – the fact that Smith, in a very rare studio moment when it comes to profanity, actually says "get your fucking voice out of my head" is almost shocking. When the song ends in an open-ended blast of feedback and cymbal shimmers and general dourness, it could be easy to assume that the rest of the album would follow the tone set.

And it absolutely doesn’t. It’s not that there hadn’t been variety or unexpected shifts on a Cure album before – 1984’s The Top is a good example, with the similarly sprawling and on the edge punch of ‘Shake Dog Shake’ leading into the reflective yearning of ‘Bird Mad Girl’. But following ‘The Kiss’ with ‘Catch’ is almost the perfect definition of a 180 turn, and again, if the idea was to project confidence in the band doing whatever the heck it wanted to, the group nailed it. Unsurprisingly a single, one of the album’s four, and less than half as short as ‘The Kiss’ was, ‘Catch’ seemingly exists as a perfect fillip, light and breezy sounding, Smith in regret and reflection mode rather than rage. Williams’s drumming, his skilled and just-so intros now a firm part of what the band could do, kicks it off and sets a gentle tone, and from there it’s also sweet sorrow in the gentle sway of the singing, the bursts of acoustic guitar here and there, the violin keyboard part. Tim Pope’s video for the song so excellently captures the feeling of the song, the idea of something delicate and sun-kissed playing while wandering the Mediterranean coast of France.

There’s also an elegant, if potentially twisted, trick in that the song’s about someone in the narrator’s past, but is also directed about someone new and present, the type of thing where the song is so instantly captivating that the impact of the opening line – “Yeah I know who you remind me of” – can slip by if you’re not careful. In the same way as The Head On The Door’s ‘A Night Like This’ almost implies, there’s almost the hint of the unreliable narrator here, or that there’s an incomplete story told where there are three figures involved but only one is heard from directly. It’s not something unique to Smith of course, but it’s also a sign of a just careful enough lyricist, able to move beyond strict personal/autobiographical depictions or I/you interactions to consider something a little more complicated, perhaps a touch more ‘real’ if you like.

Breaking down the sequencing and the song-by-song flow from here would be too much for a shorter piece like this, but by considering this start, much of the rest of the album’s unexpected logic reveals itself – it is not one thing, it will resist being one thing. To reiterate, this was never new to The Cure, much less to the world of music, but the position the group had found itself in – as a veteran act almost to their surprise, able to draw on an already deep catalogue while revealing themselves to be just as present and energetic in their current moment – underscores the sense of statement of purpose at work. By the late eighties the double album had become a cliche several times over in any number of musical fields, and the feeling was that if you had one for release, it had better be really good. As it turned out, 1987 really was a great year for double albums – just ask Prince. And Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me is right up there.

It’s not without flaw, per se. At times in relistening to the album now, you can start to sense particular patterns – there’s a variety throughout, but there are still general types of songs at work. There are plenty of examples of the split between the deep, longer album cuts and the concise, immediate singles at work, and more on both later. But it could be argued in turn that there’s a happy slumgullion of approaches being tested out – almost as if the band aren’t so much musicians as, indeed, cooks, refining or exploring a few recipes and making all results available to the public for their judgment. The Cure had already self-defined an intentionally mutable space – why not stake it out further, on all fronts?

Some time should be spent on the songs that were neither singles nor the long epics, though – if not every one, then some notable examples. ‘One More Time’ explores a slow and dreamy side but there’s a sense of bright focus here, underscored of course by what can simply be called one of Smith’s most beautiful, lovely guitar parts ever. It’s one of those simple things that just SOUNDS so perfect, and you want to do a slow dance. (Well, you do if you’re me.) Then there’s the equally sweet and stately keyboards throughout, one part after another providing texture, shape and light. And again, when Smith emerges, it’s after half the song has gone and with another in his spot-on opening gambits: “I’d like to touch the sky tonight.” (It’s also well worth noting how for all the parodies and complaints from some about his voice, Smith never sounds less that wonderful throughout the album. Even on this song when he launches to a higher register towards the end, his voice never breaks, arcing up then settling down as the keyboards follow him.

There’s ‘How Beautiful You Are’, the most self-consciously French song given that the album was recorded in that country, almost verging on the stereotypical thanks to the mock accordion with its suggestion of the boulevardier, as well as the opening lyrical reference to, well, Paris in the rain. (There’s also something to be said that, heard from all this distance of years away, said accordion’s gentle drones and the quick steady clip of the song as a whole sounds like a slightly peppier version of Disintegration’s ‘Lovesong’, perhaps an unexpected dry run for that smash hit in two years’ time.) This time around the tangle of perceptions and assumptions about a romantic other comes partially from a trio of poor Parisians proclaiming the object of desire’s beauty, silently, only for the narrator to be taken aback by how said romantic other reacts angrily to being stared at – or, if you like, at having to put up with the unwanted male gaze in triplicate. A further musical note: this is another one of those example in the Cure’s body of work where guitar doesn’t define the song – it’s the lyric, the piano, the accordion elements which are the foreground.

Then there’s ‘Like Cockatoos’, opening with a clattering swirl of notes that could be a strange birdsong, or perhaps a musical representation of a murmuration. With Williams’ count-off on the drums coming after a moodily mysterious guitar figure, it shifts into a particular exotica that Smith has an ear and obsession for, one of several examples on the album. It’s less the feeling of something specifically ‘Indian’ or ‘Middle Eastern’ or other, too easily stereotypical summations of what whole ranges of music are like through a Western ear, and more like aiming for a suggestion of feeling that can’t be pinned down. (Almost like how the sixties psychedelia that underpins so much of what The Cure has done doesn’t return directly to the source material in turn but wanted to work in the spaces that it opened up instead. A great, dark Gallup bassline, persistently matching the guitar, drives the song and almost overshadow – again, once they arrive – Smith’s muffled vocals, like he’s talking through a bit of gauze, almost in sing-speak. As for the lyrics, they detail what seems like a suburban breakup on the street, but all the descriptive moments and the weird twists turn into real psychodrama, something the string synths and the returning swirl at the end underscore. Rain falls like blood, houses seem to stare "like all the faces that quiz you when you smile", all while the night "sang out" like cockatoos. If it’s melodrama, it’s melodrama oppressed and compressed, a slow flow that culminates in an overwhelming keyboard part and one last blast of mock birdsong.

And so on – I could explore most of the songs, really, and I already can imagine friends of long standing asking why I didn’t talk about ‘Fight’ (the crushing and strident album closer) or ‘Torture’ or ‘The Perfect Girl’, but people have their favourites. Let me also salute Arthur Brennan, whose guest saxophone turns on ‘Hey You!!!’ and ‘Icing Sugar’ help make those two very different but equally great songs even better. But instead let me go back to that initial split, talking about the really long drawn out songs and the singles. The other two key examples of the former approach are just as great as ‘The Kiss’, on some days they might even be better. ‘If Only Tonight We Could Sleep’ is one of those deep cuts that people end up covering a lot – I can think of several off the top of my head, from the Deftones to at least two different Spanish-language versions. The sitar keyboards and one of Williams’ most creatively snaky drum performances, the crackling descent of the guitars, the first wordless moan of the vocal, all that and more leading up to Smith’s introduction of impossible scenarios and dreams. The sleep he wishes for is on a bed made of flowers, but he also wants himself and his partner to "fall into a deathless spell", to "slide into deep black water’. The latter is perhaps akin to the scenario from ‘The Drowning Man’ from Faith, only here he punctuates the wish with “and BREATHE!” Add in angels with burning eyes and more, Smith’s irregular use of a flute adding even more to the mystery, and honestly I could listen to that song forever.

‘The Snakepit’ is another of the longest of the album’s songs and the third in the set of slow, murky entrancers, almost halfway between the blistering anger of ‘The Kiss’ and ‘If Only’s swirling collapse, if tending a hair towards the latter musically. But with a title like ‘The Snakepit’ one can imagine it’s not exactly a happy reverie. Unsurprisingly, like the other two, like so many other songs on the album, the words aren’t immediate, with over two minutes of circular, obsessive musical scene setting playing out, first, and then, once again, a hell of an opening lyric: “Lying on the ground and thinking that it’s Christmas.” At his best, Smith has an eye and ear for a moment that might normally close a song, a story, something, and have it be the starting point for whatever might happen next, or might have already happened that needs telling. Flutes suddenly leap up and fade, Smith’s voice is at its most surrendered to the flow, where it seems almost like the echo is much more dominant than the actual singing. When those flutes reemerge to become the lead element in the song, then the sole one as the song, almost like a procession, moves towards its end, it almost could be waking up from a dream.

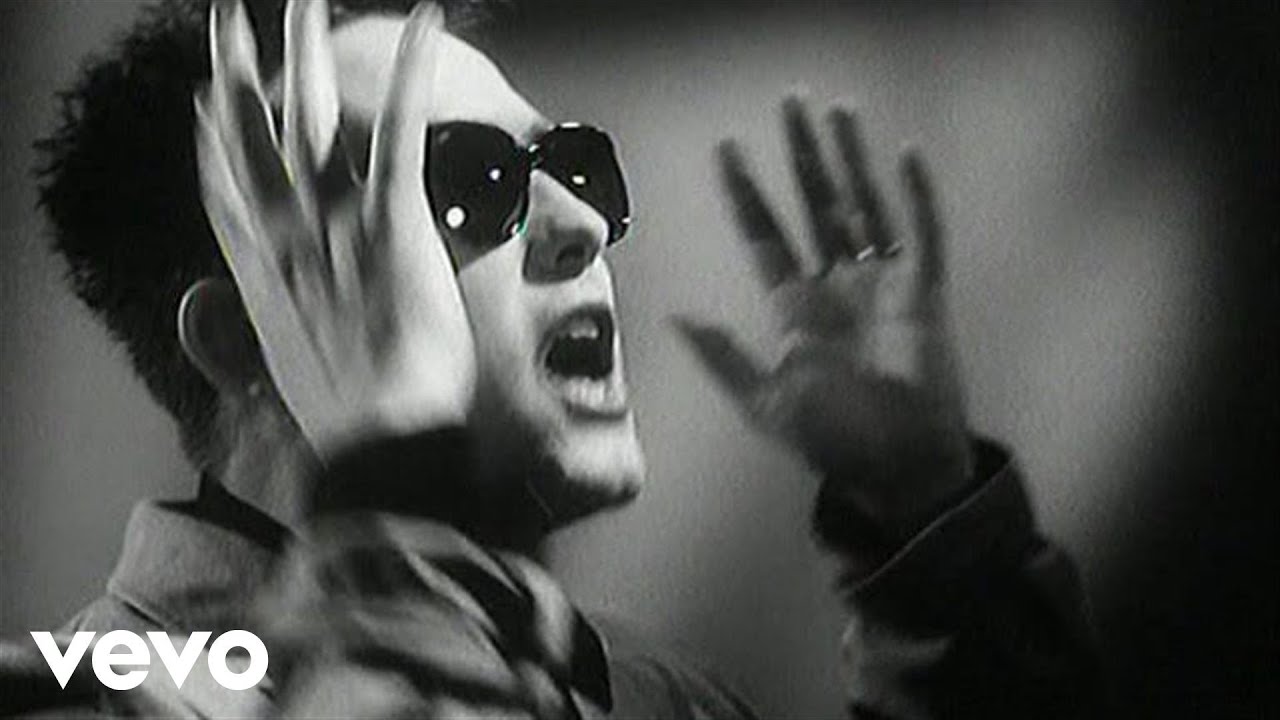

And the rest of the singles? Once again we can thank video director Tim Pope for cementing certain images in our head to go with the music, and having the two play off each other perfectly, as already noted with the “Catch” video. Whatever bit of genius caused him to think of putting Smith into a headless bear costume in the ‘Why Can’t I Be You?’ video, or to dress up Williams as a vampire or just to have the whole band spell out something in their own version of The Village People’s ‘YMCA’ dance, it all resulted in a perfect party. Is it the closest The Cure got to doing The Smiths doing Motown? (And would they be pleased at the comparison?) It’s so bright, almost brittle, but what a hop, and the contrast to the lyrics is an accomplished switcheroo, Smith as an avatar of romantic obsession/desperation and maybe just a little bit of evil or recurrent desire with the bit about being hungry…again! Points also for coming up with the “delicate/angelicate” couplet, because why force a rhyme when you can just make up the word?

Then there’s ‘Hot Hot Hot!!!’ the second three exclamation point song after ‘Hey You!!!’ but this was the one that got the wider nod (as opposed to being excised from the American CD for years). If ‘Hot Hot Hot!!!’ was the most self-consciously funky, in a classic pop sense at least, that The Cure ever got, well, why not? In a time where there was a lot of really, really bad (and dare I say really white) late 80s funk on the pop charts – if you didn’t live through it, you have no idea how bad it could get, but at least the good stuff stood out all the more – this feels like a not-too-heavily-laboured-over effort that’s actually quite good. The way that Smith wraps up choruses and then draws out ‘hot’ into more syllables and sounds is a treat, but there’s also his lead ups to the verses, even the start of the song. It’s almost like there’s something in him that had to escape a bit vocally, a fevered feeling indeed.

But still, it all comes back to ‘Just Like Heaven’ in the end. It’s the one that seemingly everyone knows thanks to any number of covers and live remakes and 80s retro radio and more. It really has easily and simply become a real pop classic, almost certainly the one song that everyone probably knows by The Cure to this day. It’s three and a half minutes of brilliance where absolutely nothing is wasted and everything is necessary.

In many ways, it summarises this kaleidoscopic album as well. Smith not taking a vocal straight from the start? Check. Williams kicking it off instead with a great drum fill, one which Smith says inspired him to do that lovely instrument-by-instrument build of the opening arrangement? Check. The way said build, again, instantly showcases to anyone who’d care to listen that there’s a tight ensemble fully at work here, whether it’s Gallup’s bassline, Thompson’s backing guitar, whoever it was that played that couldn’t-be-any-better descending keyboard line, Smith’s own exuberant and now near trademark guitar part in turn? Check. A killer, immediately attention grabbing opening line? Show me show me show me indeed.

How many moments can I single out in this song, when it seems to be nothing BUT exquisite moments. (And again, what a great video, one of the most straightforward ones from Pope perhaps but so beautifully shot – almost nothing else like it at the time, with a real sense of how to use light and shadow and even a guest appearance from the soon to become Mrs. Smith herself, Mary, the song’s inspiration.) So here’s a moment: the bridge leading out of the first chorus, and even more specifically, right after that excellent bridge. Even the way he repeats “just like a dream” is a lovely, spot-on touch, and having the piano take lead from there adds a new sprightliness and a bit of melancholy in turn. And that’s the thing: for all the exuberance, it’s not a happy song! Or at least, I can’t think of many happy songs where the final verse ends with a note of sad regret like: “And found myself alone, alone, alone above a raging sea/That stole the only girl I loved/and drowned her deep inside of me.”

I very suddenly, quite literally as I’m typing this final paragraph, remembered a moment the following year after I first heard ‘Just Like Heaven’, at my high school graduation party, dancing to this song, and a couple of more tangled memories with that. Maybe it was always meant to be a kind of anthem for any number of moments like that, where bliss and melancholy wrapped together tight, all with really good music to underscore it and set the tone. I guess I was just lucky enough to get that moment, at least, when it first hit. Susan’s still a friend and agrees she might have been a bit hasty – ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ is still her favourite – but if ‘Just Like Heaven’ was a sellout, teenage me didn’t know the difference, and adult me is glad it was. It, like the band, like the album it came from, is one truly singular prospect, and I couldn’t wish it to be any other way.