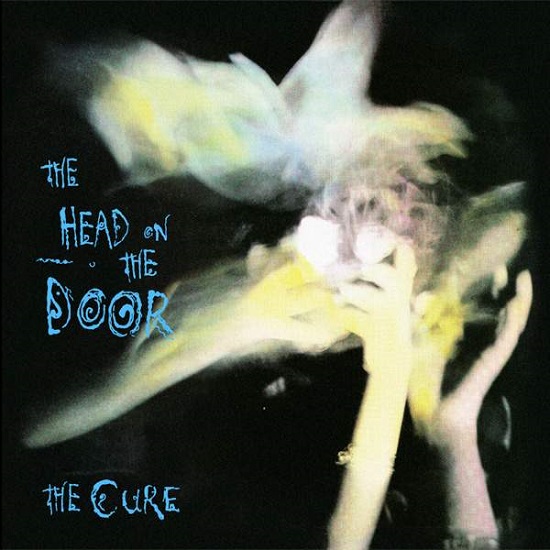

It only occurred to me in recent times that there’s something more than a little remarkable about The Cure’s The Head On The Door, celebrating its 35th anniversary this year. It’s short.

Then again it’s not that remarkable, really. Up until then every Cure album was about the same length as this one, two sides of vinyl, around forty minutes. The Head On The Door itself is around thirty-eight minutes. That’s not per se remarkable, until you think about the band’s career since then. Every album they’ve released since – singles compilations, remix collections, live releases, not to mention actual full studio albums – has been notably longer. Even the original Standing On A Beach: The Singles, released one year later in 1986, was longer, and then longer again thanks to both an expanded CD release and a cassette release that had a slew of B-sides making up the second half. The Cure have come to stand for packed to the brim efforts, and The Head On The Door was the last time you could talk about one of their albums in terms of briskness and brevity.

That isn’t to complain about what followed. (Not in the least: you will take my copy of Disintegration from me from my cold dead hands and one day, ONE DAY, Robert Smith will finally get around to authorizing those Mixed Up and Wish remasters, for a start.) As for what immediately followed in terms of a proper album, Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me put everything the band had done together up until that point, made it even more kaleidoscopic and had an actual American breakthrough into the Top 40 to boot. But The Head On The Door is almost what I might choose for someone who wanted to know ‘what’s a good Cure album to start with’, beyond a singles comp or a mixtape or a playlist (you’ll never seem to find someone saying what Cure song to start with, there are too many to choose from, in the best sense; if there’s a Cure song that accurately and absolutely sums them up…well, I wouldn’t know what to pick, would you?). Ten songs, just so.

It’s an album that feels like what it was – a full fresh start and raring to go. Not that they had suddenly returned, but ever since the band’s collapse in 1982 after the Pornography tour, what had occurred felt like a slow but sure reassembling amid Smith’s various stints and collaborations and production work elsewhere. First it was Smith and drummer-turned-keyboardist Lol Tolhurst getting down to brass tacks and coming up with an unexpected pop hit in ‘Let’s Go To Bed’, also their in-retrospect crucial start of their long-running video collaboration with Tim Pope, with subsequent singles continuing that path. Then it was The Top, almost a solo album in all but name, extreme and fraught at many points but also with a sweet confection in ‘The Caterpillar’, along with a full tour with a bigger line-up than ever that included album guest and now second guitarist Porl Thompson, who had originally been in the group in the Easy Cure days. Drummer Boris Williams was drafted in towards the tour’s end and after that Simon Gallup returned on bass – and all of a sudden, that was it, and everything seemed to click.

History of course showed that this was still temporary as within a few years Tolhurst was out, Roger O’Donnell was in and out again for one of his irregular stints with the group, and by 1990 Perry Bamonte was on board, and things progressed from there. But the conception of the group growing out of The Top tour as a quintet or at least as something expanded was solidified, something that arguably reflected both the wider range of music Smith and his cohorts were creating and their own increasing success. Less the defunct Jam, despite the Chris Parry connection, and more Depeche Mode or even Iron Maiden – an increasingly entrenched, stalwart UK act that racked up US pop hits to the consternation of those who couldn’t imagine it, with an already memorable backstory and back catalogue, an obsessed and easily identifiable fanbase and a willingness to tour America and Europe that was producing bigger dividends the more they hit the road. Little surprise all three acts still thrive to this day, on their own respective terms.

That said, much like The Top, The Head On The Door has the feeling of a solo effort in that Smith holds all the music credits, something that wouldn’t recur. But unlike The Top’s near total isolation and inward drama, The Head On The Door looks outward and brims with confidence, not least in the respective choices of opening songs – no ‘Shake Dog Shake’ and wailing anger, instead, New Order. Well, not really, but ‘In Between Days’ may be as famous for a bit of Peter Hook-style bass as for its video of dancing socks, swinging camera and black-light makeup. Above all else, it’s just a good song, sprightly, immediate, contrasting with the lyrical sentiments about feeling old and a love triangle’s aftermath with rushed acoustic guitar, musical hooks for days and a simple but perfect keyboard part that was the cherry on the cake. It feels like summer, a ruinous summer perhaps of mixed weather and mixed emotions, but summer nonetheless. All that and it starts with a perfect drum fill by Williams, who as the one truly new member was at once the wild card and the secret weapon for the next seven years; The Head On The Door is as much his introductory showcase as anything else.

From there the album takes its turns, feeling like a stage show, balancing the opening giddiness with the slow, elegant descent of the closing ‘Sinking’, turning the distanced, lost feeling of Faith’s ‘The Drowning Man’’s harrowing personal apocalypse into a lush, murmuring sigh with an especially beautiful break, the longest song on the album at five minutes and still short compared to a number of songs they’d done previously. And quite literally in between, eight further songs of moods and shifts. Some of which seemed weightier than they are – ‘The Blood’, as in “I am paralysed by the blood of Christ”, sure seems like a sudden turn for a band not exactly known for religious belief, but when Smith explained in interviews he was referring to a Portuguese red called Porto Lagrima, referring to Christ’s tears, then both the hints of flamenco and the reeling stop-start feeling of the song make perfect sense.

Other hints of their increasing worldliness in a literal sense crop up elsewhere – ‘Kyoto Song’ doesn’t explicitly discuss the Japanese city but the arrangement hints, at least in a general fashion, of a performance on a stringed instrument like the koto mashed up with a contemporary Cocteau Twins arrangement, all while Smith sings a lyric about a disturbed sleep and vivid, almost visceral dream imagery. It’s also another point where his lightly treated vocals don’t quite sound the same as before or after on the album – there’s a lot of understated vocal experimentation from Smith throughout this album, either in his delivery or how his vocals are treated, a further expansion of his previous ranges (compare him here with how he was just six years previously on Three Imaginary Boys and you can sense both the confidence and, quite literally, how he had grown up).

His commanding sweep on ‘The Baby Screams’, a dramatic flow of a song in the vein of ‘The Walk’ accentuated by both relentless electronic pulses and ghostly piano parts, differs again from his up-and-down lope on the staccato and idiosyncratic ‘Six Different Ways’ – a song that seems like it’s going to live up its name within the opening thirty seconds before settling into its own engaging groove. The soaring ‘Push’, featuring a beautiful descending lead guitar melody that Smith only joins in on halfway through the song and then takes an echoed spotlight turn over, is much different again from the taut, almost crabbed punch of ‘Screw’, Gallup’s distorted bass a tortured thing that Smith almost seems to mockingly breeze past as keyboards bubble in his wake. In all these cases too, it’s not just Smith for all that he wrote everything – there’s something about sensing the quintet at work, Smith primus inter pares in the end, throughout the album. Everyone seems to have at least one sudden standout moment per song, just the right hit; hitting the unexpected money note. Credit David Allen’s production as well, the first of several such collaborations he did with the band; here still some years away from the near cinematic sweep of Disintegration he’s already shown the facility in many modes that would flower even further on Kiss Me.

And then there’s the other singles. The other day, writer Douglas Wolk said on Twitter, “JUST realized that the album version of "Close to Me" does not include the brass-band part at the end. WHAT WERE THEY THINKINNNNNG.” It is a little weird not to hear that extra explosion of horns at the end and at points throughout the song – so popular and memorable was that single remix – but even in its original form, ‘Close To Me’ is a perfect little delight, as minimal a pop song as the band had done at that point, but almost literally so. It’s almost all Williams and Gallup’s rhythm section, the latter’s part a ridiculously catchy moment in its own right, punctuating handclaps and another twinkly little keyboard melody or two, Smith singing both lead and a little backing rhythm of his own, a breathless winsome anticipation with just a bit of raw desire via sighs and slurps. It might almost be their purest synth-pop song as such, and it’s not too hard to hear a later indie-rock take on that, from the Magnetic Fields to the Postal Service and more, getting some inspiration here. Not for nothing did Tim Pope pull another visual rabbit out of his hat for this one, taking both the intimate feeling and the titular image to present a setting purportedly showing the group stuffed in a wardrobe on a cliff, then going over the edge in said wardrobe and apparently drowning, all while still playing as best they could on such things as combs.

Meanwhile, ‘A Night Like This’ wasn’t a formally issued single per se, but it too got the Tim Pope video treatment – and it’s one of his most straightforward efforts, perhaps suiting the song itself. There’s nothing quirky, goofy or the like about it, and on an album where there’s a lot of space in the arrangements, just a little silence and restraint letting all the instruments lock in around each other, ‘A Night Like This’ is one of the fullest sounding numbers, sweeping and strong while retaining a mournful undertow, guest saxophone by Ron Howe making for a perfect extra touch, something seemingly very eighties but much removed from the oily associations that instrument had often gathered by that point in mainstream pop. Smith’s lyric, another portrayal of romantic collapse, is a tangled mess of emotion; despairing, angry and regretful. He delivers it winningly, vocals sometimes spiteful, sometimes calm, sometimes yearning. It’s all the more powerful because at no point is it clear the other person even feels anything like the narrator does.

The Head On The Door broke into the Top Ten in the UK, its singles were Top 40 hits here too, and elsewhere they racked up further successes, including hitting the Top 75 in America, with the now entrenched modern/college rock circuit turning the band into an powerhouse. A French tour appearance resulted in another Tim Pope-directed effort, their debut concert film The Cure In Orange, catching the band in excellent form. His videos gained further MTV airplay in turn for the band and the world was primed for the band when they returned with ‘Just Like Heaven’ a couple of years later. It’s easy to look back now and say everything that happened afterwards was inevitable – given the twists and turns of the group’s history up until that point. Nobody could have been blamed for presuming that another full line-up reworking to a total collapse was just around the corner. But if that had happened, The Head On The Door would remain what it is, an immediate pleasure of the moment in the year of such albums as Hunting High And Low, Songs From The Big Chair and Around The World In A Day and like all of them one that happily lasts in its own right down the line – even if it’s over before you know it.