In 1989, I was a callow nineteen year-old intent on devouring as much new music as his ears would allow. Wednesday mornings were set aside to read NME, Melody Maker and Sounds cover-to-cover, and a lifetime of tinnitus was launched by my five-gigs-a-week habit. Perhaps unsurprisingly, 1989 was my annus mirabilis for new album releases, twelve months of incredible albums that I would cherish as only an obsessive youth could.

In 1989, Pixies gave us Doolittle and The Stone Roses unleashed their debut album. Like most doting indie kids, I loved both records with a fanatical passion. I also was infatuated by De La Soul’s groundbreaking Three Feet High & Rising, NWA’s incendiary Straight Outta Compton and the cool vibes of Soul II Soul’s Club Classics Volume 1, while also finding time to swoon over Hunkpapa by Throwing Muses, Technique by New Order, Spaceman 3’s Playing With Fire and Neneh Cherry’s indefatigable Raw Like Sushi. Genuinely marvellous albums by Lou Reed (New York), Kate Bush (The Sensual World) and The Beastie Boys (Paul’s Boutique) would barely get a look in.

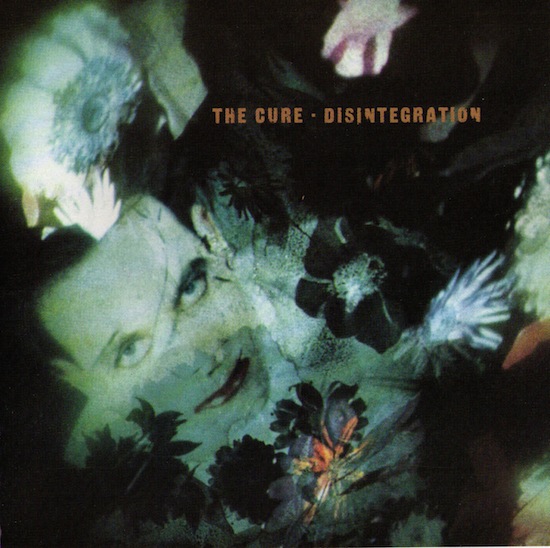

However, even set against these rivals, one album would rule them all. In May 1989, The Cure would release their eighth studio album, Disintegration, which was described at the time by tQ’s Chris Roberts in his Melody Maker review as being "as much fun as losing a limb". But for me, who had only ever previously flirted with The Cure’s musical output, it sounded like one of the greatest albums I’d ever heard. The fact that much of Disintegration was a funereal dirge, with lyrics reeking of self-absorbed self-flagellation, mattered not a jot. In a year of mighty albums, Disintegration was The Daddy.

Weighing in at over 72 gloriously claustrophobic minutes, Disintegration was a mass of self-pity, crocodilian remorse and existential angst set to a backdrop of ocean-sized keyboards, dense guitars and a relentless intensity that pulled the listener under. However, as was typical of The Cure, a generous helping of twinkling melodies provided perfectly-spaced gulps of oxygen and ensured Disintegration contained some of The Cure’s finest songs, be it the ominous plod of ‘Lullaby’, the cascading emo-pop of ‘Pictures Of You’ or the utterly monumental vent spleen of the title track.

Despite its decided lack of jollity, I was smitten with Disintegration. My love was so all encompassing that I can (ashamedly) recall a (mercifully short) period of falling asleep each night to the nine-minute goth-hymn, ‘The Same Deep Water As You’.

But while I rejoiced in the album’s grand despair, Disintegration had been conceived during an annus horribilis for the band’s principle songwriter, Robert Smith. During April 1988 he had hit the ripening age of 29, and had become depressed and obsessed with delivering a "masterpiece" before hitting the big 3-0. In some ways, Smith’s despondency was at odds with the The Cure’s rarefied status as a globally-renowned alternative rock group. Their previous album, 1987’s double Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me felt like a celebration of the band’s first decade, mixing whimsical pop (step forward ‘Why Can’t I Be You?’ and ‘Catch’) with a bleak underbelly on tracks such as ‘The Kiss’ and ‘Torture’. The album helped The Cure crack mainstream America, and ensured that a group formed in Sussex in 1976 could, a little over ten years later, play arena-sized shows in virtually any country they visited.

Robert Smith, however, was not a happy bunny. Believing that most bands delivered their masterpiece by the time they were thirty, he set about writing "the most intense thing The Cure have ever done". Later, he would admit that "the darker side of Disintegration came from the fact I was going to be thirty." In many ways, Disintegration felt like a prototype of a Robert Smith solo album, from the single portrait cover artwork, to the relentless self-analysis within the album’s dozen songs. "I would have been quite happy to make those songs on my own, if that band hadn’t liked them," Smith would reveal.

His fellow bandmates did, however, like Smith’s new material, and the recording sessions for Disintegration took place at Hook End Manor Studios in Reading. The atmosphere was particularly toxic. Smith was in a depressed, non-communicative state ("one of my non-talking modes"), as he fretted over creating an album that contained the doom-laden gravitas of 1982’s brilliant Pornography album. "I actually wanted an environment that was unpleasant," he would recall, and a combination of his own truculence and keyboard player (and original member) Lol Tolhurst’s raging alcoholism would ensure the creation of Disintegration was a pretty miserable experience for The Cure.

This was compounded by the sacking of Tolhurst. Smith had become concerned that his old school friend would steadily drink himself to death if he remained in The Cure, and despite Tolhurst attending a brief stint in rehab, things came to a head during a mixing session for Disintegration at RAK Studios in London, during which Smith and a drunk Tolhurst had a stormy exchange with the latter infamously deriding Disintegration as "half of it [being] good and half not a Cure record."

While Tolhurst was officially sacked in February 1989, he had been replaced on the Disintegration sessions by Roger O’Donnell. O’Donnell was a much more proficient keyboardist and his cinematic use of ‘walls of synthesizers’ would become the cornerstone of the record’s dense charm, from the gothic funeral march on the opening mood-setter ‘Plainsong’ onward. Rather cuttingly, in the album’s list of credits Lol Tolhurst’s contribution was summarised as ‘other instrument’.

But, as is often the case, amid this unpleasantness the songs began to emerge. Lead single ‘Lullaby’ proved the calm before the emotional storm, a perfect moment of twisted pop for which Smith took inspiration from creepy lullabies his own father would sing to him. The song’s video, directed by Tim Pope, was an arachnophobic vision of hell in which Smith was seemingly eaten by a giant spider.

However, visceral self-flagellation was at the core of Disintegration. The dense ‘Closedown’ was list of personality failings, while the portentous ‘Last Dance’ ached with memories of fleeting happiness. Even on the pristine ‘Pictures Of You’ – a positively upbeat ditty relative to the surrounding gloom – saw Smith chiding himself about failed relationships ("If only I’d thought of the right words / I could have held onto your heart") and while his desire to torment himself via his lyrics wasn’t a new concept, Disintegration saw Smith perfect the craft of self-annihilation.

Amid the turmoil was a moment of redemption. ‘Lovesong’ was, indeed, a straight up love song Smith had written to his wife, Mary Poole. The pair had been married in August 1988, and the song acted as a wedding gift. "I couldn’t think of what to give her," Smith would later (half) joke about a song that sounded at odds with the rest of Disintegration. "It’s taken me ten years to get to the point where I felt comfortable singing a straightforward love song. If that song wasn’t on the record, it would be very easy to dismiss the album as having a certain mood."

But even ‘Lovesong’ revealed the scars that fuelled Disintegration and that obsession of approaching 30 ("Whenever I’m alone with you / You make me feel like I am young again,") while the driving throb of ‘Fascination Street’ spoke of "Pull on your hair and pull on your pout" in an act of defiant showmanship and a mirror into Smith’s view of his celebrity status. In stark contrast, ‘Prayers For Rain’ was a beautiful sonic death mask.

While The Cure’s American record label hated Disintegration on first listen ("there was just this look of absolute dismay on their faces," Smith would confirm) – Elektra wrote to the band accusing them of "committing commercial suicide" and being "wilfully obscure" – the album was a worldwide hit. Selling in excess of 2.6 million copies, Disintegration ensured that despite Smith’s best efforts The Cure had "become everything I didn’t want us to become – a stadium rock band."

And a miserable stadium rock band at that. Chris Roberts’ wonderful Melody Maker review offered up a perplexing conundrum – "how can a group this disturbing and depressing be so popular?" Pretty easily, if the truth be known, and Roberts needn’t have looked further than the peerless title track. Clocking in at a touch under eight-and-a-half minutes (a full five minutes longer than my usual song attention span), ‘Disintegration’ was a sprawling, reeling act of desperation, on which Smith unlocked a Pandora’s Box of self-loathing. "I miss the kiss of treachery / The shameless kiss of vanity," he began before lurching into "I never said I would stay to the end / I knew I would leave you with babies and everything," a line I always felt particularly harsh on his newlywed status. By the song’s heart stopping crescendo, the singer seemed to be bumping along rock bottom as he screamed "Now that I know that I’m breaking to pieces / I’ll pull out my heart and feed it to anyone." It was almost too much – too transparent and psychologically invasive. The following two album-closing songs – ‘Homesick’ and ‘Untitled’ – felt like the comedown from a heavy dose of grief.

The sleeve notes for Disintegration contained a request – ‘This music has been mixed to be played loud, so turn it up’. In 1989 I did as I was told, and allowed Robert Smith’s deepest fears to seep into my psyche. In a year of brilliant albums, Disintegration was both depressing and disturbing, but also magnificent and masterful. In feeding his heart to anyone, Smith had purged his soul and delivered The Cure’s masterpiece.