What would you do on the day your first album was released? In a pre-download, pre-streaming era — and perhaps even now — a visit to a record shop would be pretty high on the list. Fifty years ago today, there’s no reason to suppose that David Bowie wouldn’t have done exactly that, no doubt negotiating piles of Sgt. Pepper’s as he did so — The Beatles album was also scheduled for a June 1 release, although in the event, stocks of their eagerly anticipated opus reached the shops a few days beforehand.

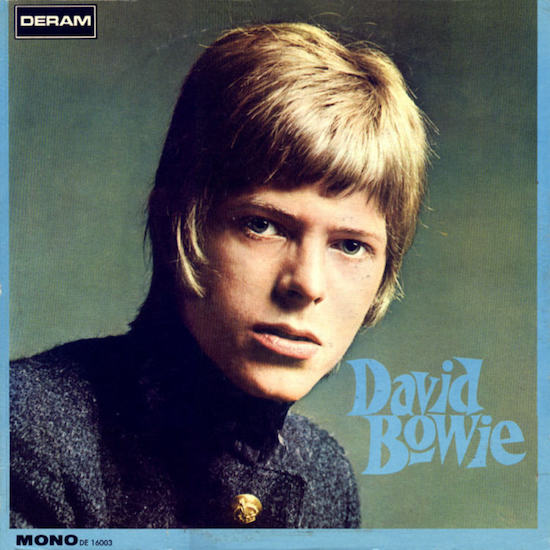

As Bowie saw his face peering out from the racks, golden hair shining before an olive green background, he must surely have fancied his chances. Two years previously, with the release of ‘Can’t Help Thinking About Me’, he had hooked up with Tony Hatch and, in doing so, jettisoned the final traces of whatever American influences he had acquired between his teenage discovery of Little Richard and the R&B leanings of his early singles with The King-Bees and The Manish Boys. And even if that single didn’t give him the breakthrough he craved, it was no less a canny move for that. The Bowie of ‘Can’t Help Thinking About Me’ has his gaze firmly fixed upon London, knowing that from his present home in the suburbs, he’s a short train ride from the centre of the universe. It’s the work of someone who knows that singing in a British accent is now more than fine. When the Americans hear it, they’ll be charmed to bits, just as they are when they hear The Beatles doing their funny press conferences.

He was ahead on the curve in this regard: ahead of Syd Barrett; ahead of Kevin Ayers; and only weeks behind Ray Davies, whose British accent only came to the fore on ‘A Well Respected Man’. Like Davies also, the Bowie that started work on his first album was sharp enough to realise that there had never been a better time draw on influences that were not readily available to American musicians. Music hall. Theatre. Camp. Victoriana. There was fun to be had here, and the resulting songs reflected that: the eccentric middle-aged protagonist of Uncle Arthur who spends his life shuttling between the gasworks where he has a job and his mum’s house where he spends his leisure time reading Batman comics; the pretty pastoral advances of ‘Come Buy My Toys’, which featured an uncredited John Renbourn on guitar and the beguiling line, “You’ve watched your father plough the fields with a ram’s horn”; ‘Maids Of Bond Street’, with its gallery of provincial dreamers, all no doubt barely disguised representations of Bowie’s own hunger to finally happen.

As big ideas go, Bowie’s new direction wasn’t a bad shout. The sessions took place at Decca’s West Hampstead studios at the end of 1966, a time when pop and rock had yet to formally mark out separate territory to each other. The pop world in which Bowie was trying to find a foothold was not the one falsely remembered by lazy documentaries and latter-day tabloid digests of the 60s. Its field of contenders did not rigidly divide into a top layer of ruling squares who suddenly found themselves under threat by long-haired insurrectionists. Pop was more nuanced and inclusive than that — a point missed by Paul Morley in 1985 when he conducted a peculiarly aggressive interview with Bowie’s manager first manager Kenneth Pitt. “What you don’t realise,” said Pitt, responding to Morley’s accusation that he was trying to mould Bowie into the new Tommy Steele, “is that in the 1960s, the Rolling Stones would have probably considered themselves to be showbiz.”

In London, The Beatles and The Stones were hanging out at the Bag O’Nails and the Scotch Of St George with the likes of Jimmy Tarbuck and Ken Dodd. Several artists would soon be scaling the charts with a seam of fragrantly orchestrated baroque pop tunes, blending music hall, psychedelia and social realism in a manner that wasn’t unappealing to older listeners. The songs that Bowie was recording were simpatico with these times. If you got it right, you could release a single that appealed to both baby boomers and their parents. By way of evidence, Bowie needed look no further than the continuing success of The Beatles, previewing their upcoming album with ‘Penny Lane’, a song which looked at the middle-aged straights going about their everyday business with an affection that could only come from someone sufficiently removed by youth, distance and success to know that they’re beyond the control of that world.

The fascination for Victoriana, pre-war military couture and music hall had a strong gravitational pull in London from 1966. Of all The Beatles’, it’s telling that it was Paul McCartney that came up with the Sgt. Pepper concept. As the only Beatle permanently based in London, he was ideally placed to notice the beginnings of this new aesthetic. In just over a year, five branches of Ian Fisk and John Paul’s I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet clothing boutique had opened, selling antique military garments to a clientele that included Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Mick Jagger and John Lennon. Enough time had passed between the pre-war music hall era and the present to render it fascinating and exotic.

Certainly this seemed to be the case with Bowie, if songs like ‘Rubber Band’ (about a soldier returning from war to find his love married to another man) and ‘Little Bombardier’ were anything to go by. He must have felt a measure of vindication when he heard what The Beatles had done on their record. While Bowie steered clear of out-and-out psychedelia on his album, a venn diagram of the two releases would see several songs that wouldn’t have sounded out of place on the other artist’s record. ‘When I’m Sixty Four’, ‘She’s Leaving Home’ and ‘Good Morning, Good Morning’ could sit comfortably alongside Bowie tune such as ‘Uncle Arthur’ and ‘Love You Till Tuesday’.

The other trope unlocked by the advent of psych was the regression to a childlike state. Once again, The Beatles were ahead of the pack with ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’ — while some of the best songs from Bowie’s album sessions also took inspiration from the way a child sees the world. ‘There Is A Happy Land’ was, in the words of Bowie blog Pushing Ahead Of The Dame, an “attempt to convey the common mind of childhood” and carried with it “the sense of childhood being a separate order, with its ranks and guilds, its legends and factions all unknown to adults. Also recorded at this time, albeit overlooked for the final track listing, was ‘When I’m Five ’ — a similarly well-observed testament of (early) youth which highlights the gravitas children attach to reaching a new age: “When I’m five/I will walk behind the soldiers in the May day parade/’Cos I’m only four and grown-ups walk too fast.”

By the end 1967, it seemed like the advent of psych had prompted every exciting British band to unleash their inner child. Subsequent albums by Traffic, Rolling Stones, The Hollies, Pink Floyd, Tomorrow and Bee Gees all snapped into line with this new orthodoxy — with The Zombies following shortly afterwards. Every one of these artists dipped into the same thematic playbox plundered by The Beatles and David Bowie. In the event, The Beatles album reached the shops a few days beforehand and would go on to be widely regarded as the greatest album of all time. By contrast, Bowie’s album stalled at a humiliating number 125 in the charts, a position which prompted his label to drop him. Received wisdom has been unkind to David Bowie in the intervening decades. The problem, perhaps, is as much to do with the way we perceive that era now. Bowie was trying to do something that sat at the intersection of pop, rock and musical theatre, but belonged to none of them. Five years later, with The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, he revisited that intersection, and in doing so he created something that truly belonged to all of them.