“Music is so important, it’s got healing powers, it helps people.”

Adrian Sherwood, On-U Sound

“We know that it have been mentioned to our great men and Ministers in Parliament by them that have Factorys how many poor they employ, forgetting at the same time how many more they would employ were they to have it done by hand as they used to do. The Poor house we find full of great lurking Boys…. I am informed by many that there will be a Revolution and that there is in Yorkshire about 30 thousand in a Correspondent Society…. The burning of Factorys or setting fire to the property of People we know is not right, but Starvation forces Nature to do that which he would not…“

A letter from “A Souldier Returned to his Wife and weeping Orphans” to a Member of Parliament from Wiltshire (1802)

Early in the 1980s my father’s siblings were rehoused, moving from Darnall in Sheffield’s industrial east end to Handsworth, a bit further out of town. When we would visit them the short drive took us along a back route, down a bare utility road. It was covered in a black residue: a mix of oil and dust that coated everything, including the struggling vegetation. It was a barren place. The road eventually led us past an imposing industrial structure, bathed in an invisible cloud of sulphurous dust: Orgreave, which literally means the pit (greave = grave) from which ore was dug.

At this point my father would ask us to wind the windows up, and not to inhale. It became a running joke when we took this route – who could last the longest. When we finally succumbed to our need for air we would laugh uncontrollably, while desperately inhaling lungfuls of that foul phlogiston. My sister, god rest her gentle soul, would be dead from a massive asthma attack not ten years later.

Back then I had no idea what this place was or how it would become a turning point in our histories. By 1984, the year of the tumultuous events, my father had already been unemployed for three years. He had lost his job with the privatisation of the steelworks near Darnall. In the endless waves of layoffs that followed, it was a lottery who kept or lost their livelihoods. We thought Dad’s stroke and subsequent breakdown were brought on by the acute stress of trying to provide for his family. Only later did I understand the deeper issues: collective trauma, fragmented communities, broken patterns of being. The life we had was gone, the illusion of social hope shattered. I lost myself in a world of electronic music, esoteric literature, and class war: FUCK THE TORIES! No friends had I; a drum machine, monosynth, and growing record collection my only company.

My bedroom window faced Sheffield’s industrial landscape, of which Orgreave was a part. On summer nights I would open my window onto it, and the distant sound of drop hammers and heavy machinery would punctuate my insomnia. But unlike the determinate pitch and regularity of a church bell – counting time, structuring time, giving order in an otherwise undifferentiated flux – the distant booming and blurred atonal clankings formed a strange temporal geometry, within which time had no fixed order, function, or meaning.

On 18 June 1984, the day of the battle, had my window been open that afternoon I would have heard the sound of collective distress as it drifted from beyond the motorway and over the hill: cries, chants, megaphones – sounds I would have not recognised – all acoustically smeared by the distance and the air they modulated. But my window was shut; with my closed-back headphones firmly over-ear, I was lost in my filter tweaking.

The strike began in March in opposition to pit closures. Over the course of a year it divided communities and families. The government’s intention was to break the power of the unions in order to bring about fundamental change in patterns of labour, eroding workers rights in favour of business interests.

“The Prime Minister last night drew a parallel between the Falklands war and the dispute in the mining industry. Speaking at a private meeting of the 1922 Committee of Conservative backbench MPs at Westminster, Mrs Thatcher said that at the time of the conflict they had had to fight the enemy without; but the enemy within, much more difficult to fight, was just as dangerous to liberty.“

The Times, 20 July 1984

The earlier Falklands War had conveniently boosted Thatcher’s popularity ratings. In calling upon the rhetoric of war, her strategy was to invoke and amplify nationalist sentiment, casting the miners as an existential threat to national security and the sanctity of British life – more dangerous than a foreign invading force, as these evil insurgents were walking among us. And so it was that the British state waged a (then) nameless war on its workers. The Battle of Orgreave was a controversial victory for the Conservative government, where a paramilitary police force was brutally deployed against striking miners.

I was told by one striking miner, Dave, who was present during the battle: “Only one side turned up with riot gear and truncheons, it was a boiling hot day – we had shorts and T-shirts. We went to peacefully picket, you would not wear clothes like that if you were going to there to knock the fuck out of someone.” Dave’s point was that the term “battle” is to some extent misleading as the conflict was very one-sided, and that the police were deliberately intimidating the miners and spoiling for a fight. “That reenactment [referring to Jeremy Deller’s film] did not come close to the real thing – it was an ambush, the police were brutal cunts, they beat one woman up, then when people went to help, they beat them up too, then got them arrested for rioting.”

Although Orgeave has become the focus of debate around the miner’s strike, the moment at which the police’s brutality became most visible, it was not an isolated incident: similar smaller but equally brutal confrontations happened at sites all around the country. The amplification of conflict at Orgreave reflected its strategic importance as a coking plant that supplied fuel to the steel industries. The train workers stood in solidarity with the miners, and had refused to transport the fuel across picket lines, and so it became a priority to break those lines.

Since the miners were Britain’s strongest organised labour force, their defeat removed significant barriers to Thatcher’s ‘no such thing as society’ agenda. The ensuing years saw this agenda driven forward, with the widespread privatisation and deregulation of social and industrial infrastructure.

Today Orgreave is seen as a turning point in British political history – as the last stand (although I don’t accept this is the case) of a traditional left-wing politics that championed collective ownership over profit making global corporations. Back then, political commentators warned of the long-term consequences of the Thatcherite agenda to asset-strip our country of its industrial infrastructure and public services. Consequently, many musicians and producers were vocal in their support for the miners’ cause, with regular benefit concerts and fundraising records. In amongst the record racks, between the indie-folk, the anarcho-punk, reggae, and industrial-noise, one record seemed to come from a very different musical lineage. Borrowing Thatcher’s now infamous slur, The Enemy Within released the 12” single ‘Support The Miners’ on Rough Trade in October 1984.

The production team behind the project consisted of British music producer Adrian Sherwood and Sugar Hill Gang drummer Keith LeBlanc. Although these two were named on the record’s inner label, the sleeve itself was unprinted (not a disco bag – where the sleeve has a large cutout in the centre so the inner label is visible without having to remove the record from its sleeve). The only information on the cover was a small sticker resembling the “coal not dole” motto of the time; this contained the project and record name, as well as a catalogue number. Thus the record’s packaging not only referenced the iconography of political agitation, but also the use of “disposable” pseudonyms as a disruptive political strategy.

‘Support The Miners’ featured a sampling drum machine, with a rhythmic structure that would become typical of American hip hop of that era. Weaving around it was sparse instrumentation and samples of speeches by miners’ leader Arthur Scargill. At the time of its release, the record’s particular political focus on white British working-class struggle was unusual in this stylistic context. Apparently there were, and still are, rumours that the record had an insert urging people to play it at 6pm, thus causing a drain on the national grid, but sadly my copy did not.

I had the privilege of speaking to Sherwood about meeting LeBlanc, the forming of The Enemy Within, and their subsequent musical output. Their musical relationship began following the release of LeBlanc’s earlier single ‘Malcom X – No Sell Out’ (Tommy Boy, November 1983). After hearing it, Sherwood travelled to New York to meet LeBlanc, who was then promptly invited to Britain where the two would work on a new record.

‘No Sell Out’ was a groundbreaking record in a number of respects. It is widely considered to be the first record to use sampled speech, where phrases are treated as rhythmic material and triggered in time to other percussive elements. Furthermore, its use of vocal samples – of, and referring to, Black civil rights activist Malcom X – mark it as a pivotal moment in the evolution of hip hop, and as foundational to hip hop’s subsequent political turn as exemplified for example by Public Enemy. Yet the immense technical, political, cultural and musical significance of this record is often overlooked in favour of more visible works of this time.

Sherwood explains how, after picking LeBlanc up from an airport in the UK, the two passed through Wapping, where they witnessed the confrontation between police and print workers. As he remarks, “This was definitely not the kind of scene that Keith had expected to see”, contradicting as it did the romantic cliches that proliferate in American representations of British urban and rural life. This chance exposure to the raw political mood of the times, civil unrest, and the struggle for political agency, formed an ideological backdrop to their initial collaboration, one that is tangibly present in their many subsequent projects.

On hearing of the pair’s intention to work together, Richard Scott of Rough Trade records suggested they release a fundraiser in support of the miners. And so Keith and Adrian started work on what was to become RTT151, The Enemy Within.

The musical similarities between ‘No Sell Out’ and The Enemy Within’s ‘Support the Miners’ are obvious: both feature LeBlanc’s signature rhythmic patterns, the use of vocal samples triggered in a rhythmic manner, and sparse instrumentation. Also, both records were released under “single-use” pseudonyms. Sherwood describes how the latter was made in a few hours, with the intention of adding guitarist Skip Macdonald and bass player Doug Wimbish (LeBlanc’s Sugarhill colleagues). However, given that neither Skip nor Doug spent much time in the UK, a pragmatic decision was made to release ‘Support The Miners’ in its current “raw” form.

For me as an avid record buyer at the time, the similarity of these two projects, as well as their relatively close release dates, gave them a sort of conceptual linkage. As if they represented part one and part two in a series of collectively considered releases – the same algorithm running in different socio-political contexts. Taken together, these two releases seemed to propose an ideological connectivity between the Black civil rights movement centred in North America, and British working-class political struggles.

However Sherwood is keen to clarify that this was not the case. Despite his childhood interest in British social history (he mentions how the combination acts to restrict political gatherings were a precursor to the trade union movement), he admits that he did not have a particularly well-formed political understanding at that time. It is, I think, indisputable that subsequent releases demonstrated increasing political awareness and acumen. But ‘Support The Miners’ laid the foundations for these later works. It is a point of origin whose rawness hints at a production style that was to evolve into some of the most musically innovative and culturally important records of the mid-1980s – notably LeBlanc’s 1986 masterpiece Major Malfunction.

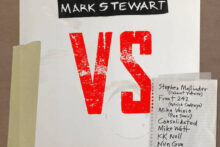

This body of work charts an approach to collective music making in which people, patterns, and processes circulate around numerous related musical projects and releases – including Fats Comet, Mark Stewart and the Maffia, Tackhead, Dub Syndicate, African Head Charge, and others. Centred on Sherwood’s label On-U sound, this interplay asserts a unique and critically engaged position in relation to the challenging political climate of the day – like some kind of multi-perspectival ideological triangulation.

On this point Sherwood refers to the notion of the version within reggae and dub musical practices, which he explains in typically pragmatic language: “If you’ve got a great rhythm I want to hear ten different cuts of it. If you’ve got a great track by Prince, and the rhythms are so good, let’s take Prince off it and make a mental dub version, or put another rapper or singer on it and have four, five, six, seven different cuts… let’s make something drastically different.” He adds that this approach is quite different to remixing: “The remix concept came from the record companies because each remix is considered to be a different version of the same track, so they all contribute towards a track’s sales figures and hence chart position.” The version, by contrast, does not function in this way: here each is considered to be a separate, often radically different, piece. To illustrate this point Sherwood cites ‘Be My (Powerstation)’ by St. Che. which shares its rhythmic backing track with LeBlanc’s ‘Heaven On Earth’. Their primary differences include pitched instrumentation, as well as different vocal samples.

For me, however, the paradigm case of versioning as it manifests in the context of the On-U catalogue is the relationship constructed between ‘Dee Jay’s Dream’ by Fats Comet, and ‘Hypnotised’ by Mark Stewart. The former, described by Sherwood as “gone wrong doo-wop” is a slick and polished production, with sparkling synthetic bells, gently sung vocals by LeBlanc proclaiming: “Everybody wants to be a DJ”, and found vocal samples that present an almost comical representation of mildly sarcastic police officers. In contrast, in ‘Hypnotised’ sounds are progressively distorted, patterns truncated, cut-up references to “obey” and military presence are added, along with the repeated phrase “7% of the population own 85% of the wealth”, and beat generation author WIlliam Burroughs reading from his text ‘The Last words of Hassan Sabbah’: “In all the streets and plazas of the world – pay it all back”. It was with some irony that Leblanc would describe this technique of sampling from diverse cultural material and current issues as “news on the beat”.

While ‘Dream’ evokes romantic connotations of hope, well-being, aspiration and popularity, ‘Hypnotised’ paints a darker dystopian vision – one of authoritarian oppression and mind control. As a young listener I was fascinated by this use of textual interplay as political discourse.

I asked Sherwood if this reading was intentional, to which he replied, “Mark (Stewart) just came up with the words.” However, given the life-long political focus of Stewart’s musical output, I find it entirely plausible that this strategy was deliberate.

My conversation with Sherwood moved on to reggae and dub, how these styles were adopted by left-wing causes during the 80s, and how, later, its fusion with punk was foundational to the Two Tone movement (including The Specials, The Selecter, The Beat, and so on).

In response to this, Sherwood spoke of the emergence of dub at a time when reggae began to increasingly advocate for Black rights and Black power. He made the point that this overt emphasis on Black issues alienated many of its white listeners, who found dub music more palatable as the words were often removed. But to be clear, this is not an attempt to mis-characterise dub music as a “silenced” or politically inert commodification. The removal of lyrics should not be equated with the removal of political voice or function.

Recalling my own early encounters with reggae and dub music at the beginning of the 1980s, typically with groups of white working-class outsiders, we listened to it precisely because it was a music of resistance, and thus also a form of resistance. Listening to this music meant that you defined yourself in opposition to the conservatism of the day, and this was far from naïve tokenism.

Against this backdrop, records such as Tackhead’s ‘What’s my mission now?’ (bw ‘Now What?’) were interpreted as putting forward overtly politicised questions. Rather than perpetuating romantic notions of hope and overcoming, the listener is directly addressed: asked to consider the stark reality of the moment, and to formulate their own response to it.

“The machines, or frames… are not broken for being upon any new construction… but in consequence of goods being wrought upon them which are of little worth, are deceptive to the eye, or disreputable to the trade, and therefore pregnant with the seeds of its destruction.“

Nottingham Review, 6 December 1811

These days the meaning of the term “Luddite” has been reduced to a simplistic dislike of, distrust for, or inability to navigate new technologies – a regressive attitude towards the technical that is often used to de-legitimise the Luddites’ cause and that of early working-class struggle. It draws from and sustains prejudices about the working class as ignorant, violent, ungrateful and uncivilised thugs. This characterisation is still called upon in contemporary discourse: one of the key rhetorical strategies used against miners during the strike was that they opposed the modernisation of the industry, where any prioritising of social benefit over business profits was framed as archaic – and were therefore “Luddite”. Those promoting socialist values were described as dinosaurs, part of a bygone age and incompatible with the technological efficiency of modern industry. The same strategic mind games are now levelled at healthcare professionals and train workers’ unions – that they are putting their own selfish needs before the modernisation of the services they work in. But how is it that “modernisation” became synonymous with deregulation – selling off hard-earned public infrastructure to global mega-corporations, against any concern for sustainability, quality, or social responsibility?

I could not find any written evidence from the period around 1810 to support the claim I’m about to make – that the Luddites were not anti-technology. But we should challenge this idea because it is foundational to a strategy that seeks to discredit social good as somehow regressive. Of course, an automated machine can relieve a manual worker of toil. But if that machine is owned by a corporation whose sole interest is increasing profit, then the absence of toil also means poverty, starvation, and hardship. I find it unlikely that the Luddites, as an emergent form of working-class political consciousness, did not understand this principle – if they had collective ownership of innovative mechanical devices, their use would offer a life free from poverty, starvation, and hardship. The same issue faces us now and in the near future, with the increasing proliferation of AI and the many tasks it is taking from humans.

Over a century following the emergence of Luddism, in 1918, the Labour Party adopted a commitment to the common ownership of the means of production. The miners’ unions fought for this, on our behalf, and for future generations. Some years after their defeat at Orgreave this clause was rewritten by the Labour leader Tony Blair. His rewrite removed any commitment to collective ownership, and spoke instead of wealth and opportunity for the many. You too can be a money maker – the only route out of poverty is everyone competing against everyone else.

I remember as a child watching optimistic TV programmes from the 1960s about future technological utopias, where robots and other automated machines gave rise to a leisure society – a society free of toil. But in the 1980s, when this leisure society seemed to arrive, it did not take the form of the long holidays, noble intellectual pursuits, and sporting activities that had been promised. Instead we had mass unemployment, the destruction of social infrastructure, the closure of shops, the dereliction of town centres, doorways to house the homeless, cheap life-destroying street drugs to numb the pain, the breakdown in community cohesion, health, and wellbeing, zero-hours contracts and a removal of workers rights. And now: shit flowing in the rivers, energy we cannot afford, doctors we cannot see, trains that don’t run, schools that can’t teach, hospitals that can’t heal, rampant housing insecurity, a life of ever increasing debt and despair for “the many”. And all the while the automated devastation of the earth’s resources adding ever increasing zeros to the balance sheet of a few global mega-corporations.

Yesterday the major link road between Sheffield and Rotherham was closed. We were diverted down a small road through an out-of-town shopping centre, past a large mound of earth, some sort of grave concealing the remains of our industrial past, and a village of identikit modern dwellings now called Waverley – a name which has a history of use by colonisers in the erasure of indigenous place names.

Hero image of injured man being escorted by police courtesy of Paige…, for Flickr (CC BY 2.0).Thanks to Adrian Sherwood, Dave Roper (miner), Ed Martin (DJ), and Maya B Kronic