“Our music, the look, black clothes, the hair, make up, skulls, mannequin heads, all that was already pretty much in place prior to going to the club, that is what we were already doing and what we were already into, so The Batcave didn’t really change us, it was more that we found a ‘home’ that fitted us.”

Mrs Fiend of Alien Sex Fiend

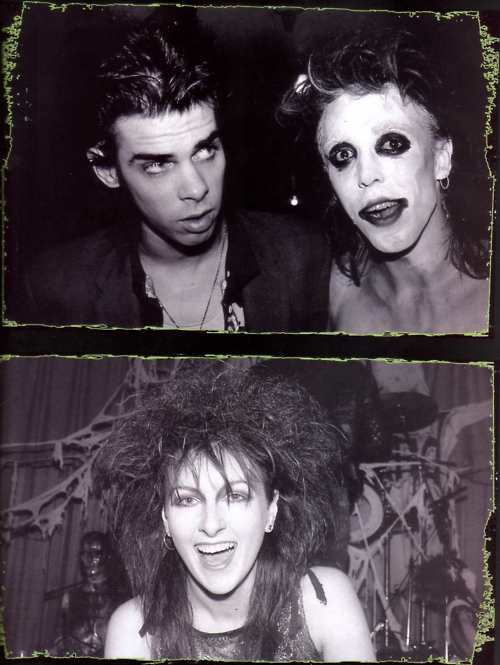

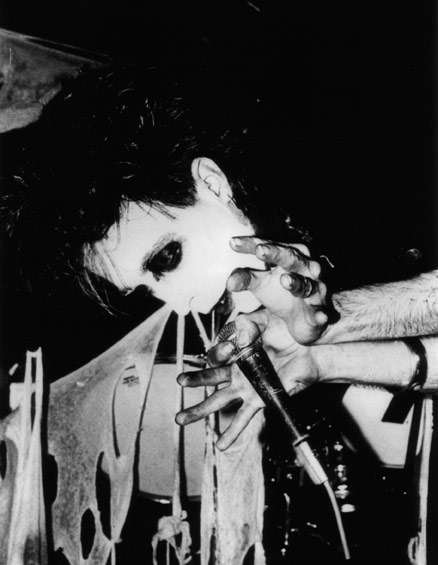

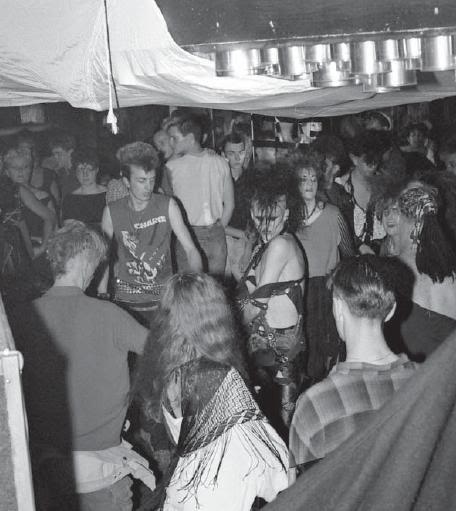

Often prefaced by the term ‘legendary’ the real Batcave Club circa 1982 would likely severely disappoint the modern day goth who romanticizes it as the birthplace of the subculture. Crude, spooky décor greeted the punters inside the venue. The walls were covered with torn bin liners stapled into place and cheesy black spiderwebs dangled from the ceiling. Then there was the clientele: free, jovial, experimenting regulars who had not a sniff of elitism about them. But something else was happening. At the bar Nik Fiend of Alien Sex Fiend could be seen chatting with Nick Cave while Marc Almond milled about the dance floor, watching Specimen play live.

What was it about the Batcave? How did it bring together those great minds, thinking just enough alike to spark an entire culture that would cross the globe and spawn a million versions of itself? Whatever it was, it has earned the venue a place in pop culture history as the Goth Garden Of Eden.

Soho’s Batcave club was opened in July 1982 by Olli Wisdom and members of his band Specimen. It welcomed everything that emerged out of the dark, decadent, oozing by-product bubbling forth from the saccharine rise of the New Romantics. The discordant and disconnected, the death-obsessed, the sexually deviant (by that society’s standards) and the cinematically horrifying and blood spattered. The term ‘gothic rock’ was already being bandied about the music press before the Batcave’s doors creaked open – famously applied to Joy Division by Paul Morley – but it was here that goth became a movement. A movement that, 30 years on, is more vibrant and varied than ever, not to mention worldwide.

“I think the Batcave’s influence definitely reached North America,” says Liisa Ladouceur, Canadian goth, journalist, and author of the Encyclopedia Gothica. “I would say specifically LA, but it even reached me when I was working in a record shop in Toronto. I first heard of the Batcave because there was a compilation of Batcave bands called Young Limbs & Numb Hymns. I just bought because of the artwork and the name. What’s funny is that it was a used record from a record store, but inside the vinyl gatefold, someone had put a newspaper clipping that was all about the club with a picture of Specimen’s Jonny Slut with his deathawk and his fishnet shirt. That was how I learned about it! Pre-internet, like a message in a bottle. They were obviously intentionally creating something there. And, in the same way that CBGBs is, it’s a name that people know, even if they never went to it.”

The original Batcave was a midweek night at Dean Street’s Gargoyle club – it would later move to larger venue The Subway in Leicester Square. And with just the same attraction it would have to goths like Ladoucuer years down the line, there was just something about its deliberately shadowy name, mood and décor that was able to lure people from the darker aesthetic side of the early 80s pop scene.

“We had read about the opening of The Batcave Club in Time Out’s listings in July 1982,” remembers Nik Fiend. “I was intrigued to read about a club that sounded somewhat different from the ‘usual old shit’! [Laughs] But that summer we were busy with the beginnings of Alien Sex Fiend – we were recording demos, doing artwork, and all that. From those demos I made a cassette tape that got a review in Melody Maker, describing us as ‘The ugliest thing in the name of music…’ amongst other things! The next thing the phone rang and it was Olli Wisdom, who said: ‘You sound like the sort of band we want to play at The Batcave’.“

“So Nik and I were invited to check out the venue at its first incarnation at The Gargoyle Club in Soho,’ says Mrs. Fiend. ‘It was raining and there was a big queue outside, but we were ushered straight into the tiny lift that went up to the club.”

“The lift would only fit in two people at a time, it was quite a ride up and we had no idea what was going to greet us at the top," says Nik. "The door opened and then there was a coffin shaped doorframe which you had to pass through. It was a real coffin with the bottom knocked out, so we knew at that point that there was something different going on!"

“But what made the biggest impression on us," says Mrs. Fiend, “was when they put on a Sex Pistols track…”

Nik: “The dancefloor cleared! en masse! We took it as a sign that people there had started moving on from punk and were looking for something different, something new.”

“It goes against the grain of popular perception, but I remember it being humourous, there was a lot of laughter there. It wasn’t po-faced – it was a laugh, you know?” remembers David J of Bauhaus, who played gigs in the club. “I mean superficially and décor-wise it was dark and gloomy for sure, but going against that, the atmosphere that was generated by the clientele was somewhat jocular.”

Bauhaus have perhaps the largest part to play in the venue’s crowd. Before it was the Batcave, Billys was name of the club’s Dean St locale, and a haunt of the now-hailed goth-fathers.

“We had a four week residency there,” says David. “It was in the really formative years of the band. I remember we’d just done a John Peel session. It was down a cobbled street and it was raining. And the Peel session was being broadcast on the night of a gig and I remember listening to it on my transistor radio outside of the club and running down the street in joy at hearing our track on the radio. Those gigs were pretty explosive, I remember once Peter (Murphy, Bauhaus singer) smashing all the mirrors on the walls – we were quite wild and abandoned in those days. And that was actually the same night that Ian Curtis came down to see us and he met us after. He was really into Bauhaus and he’d bought the two singles that we had out at the time.”

With fans of Bauhaus already attracted to the venue – including the already iconic ones – the seed was planted. But David reckons the location itself may also be responsible for setting the mood.

“It had a sort of Dickensian, Jack the Ripper flavour to it, you know, the back streets of Soho,” says David. ‘It was dingy and very much had the faded glamour of old Soho. It was romantic in that way, it was easy to project one’s gothic fantasies on that locale.”

More notable than the location, the bands or their fans are the famous faces that are said to have frequented the Batcave. Imagining the collaborations and mere conversations that may have taken place there are enough to tickle the salivary glands of any goth aficionado. Nick Cave, Robert Smith, Siouxsie Sioux and her Banshees, and Ian Astbury are just a few of the names associated with its legend.

“It was a hub for people with big hair I suppose!" says J.G. Thirlwell of Foetus. "I seem to remember it being more of a glammy type of place. A broad spectrum of people were there, and lots of girls in underwear.

“It was there one night that Lydia Lunch proposed an idea to myself, Marc Almond and Nick Cave that turned into The Immaculate Consumptive, which was a project the four of us did at Danceteria in NYC in 1983.”

But in reality the influence of the Batcave was not so direct as to affect the musicians and icons themselves. It rather made its waves on a lower, vaster frequency. No one prowling about the Batcave followed a formula. It was simply individuals expressing individuality through tools of their choosing. It just all managed to fit underneath one umbrella. Fashion, for example, is a particular focus of the club in hindsight.

“We had to make our own stuff or alter or dye things," explains Mrs. Fiend, "paint onto T-shirts, stick studs on, there was no ‘goth off the peg’."

“Johnny Melton (aka Johnny Slut) of Specimen became an image icon but I think that was down to his photo being used on the cover of Mick Mercer’s Gothic Rock book that came out in the 1990s,” she adds. “So some of the influences are things like that which people have picked up on some years later.”

“It’s funny how people talk about the Batcave ‘look’ of goth, the ripped fishnet shirt, ghoulish make-up, the deathhawk," says Ladouceur. “I mean, that was one guy! Jonny Slut from Specimen was the one who had that look and people adopted it. It’s not like everyone at the club dressed like that.”

Fashion historian and curator of the Fashion Institute of Technology Valerie Steele staged an exhibition in 2009 called Gothic Dark Glamour which in addition to documenting several stages of goth and the influence it had on top fashion designers, included a section dedicated to the fashion of the Batcave. Johnny Slut and Jon Klein of Specimen appeared to discuss their home made clobber that inspired the clubgoers of the time. Steele herself explained the influence of the club as being apart from the other more associated imagery of goth, such as Vampires, haunted houses, the undead and other elements of the supernatural. With its Bowie glam and undefined she said, the idea of a club’s role in such a movement is less dynamic and fantastical than the aforementioned mystic elements as its roots.

“The club is a literal environment,” she said. “It’s not an imaginative environment, so something like the laboratory or the ruined castle in a way is more imaginatively evocative.”

Of course, to those that were never at the club, to those who read of it as magical place that spawned the subculture, they only touch it from a distance and discern their own assumptions of what it was like. The romanticism involved in creating the popularized idea of the ‘legendary Batcave’ is, in itself, very goth. In terms of music, the name alone has even been carried beyond the club’s lifespan as a genre in some circles.

“The term Batcave to describe a sound of music has its origins in that club,” says Ladouceur. “A band like Alien Sex Fiend, their particular sound became the Batcave sound. Although I don’t think it’s as common as a term like ‘deathrock’ is, in Eastern Europe for example people say Batcave or Batcave music as a genre, giving a resonance to that club.”

In gauging the club’s role in the evolution of goth music, Ladouceur created a goth band family tree inferring that the Batcave sound is a product of punk and new romantic genres, separate from post-punk.

But again, as with the fashion, not all bands that played there can be associated with that sound. Bauhaus, for one, may be known as a band who were there at the beginning and are linked with goth for eternity whether they like it or not, but their view on the other ‘Batcave’ bands such as Alien Sex Fiend and Specimen was less than flattering.

“We weren’t too impressed,” says David J. “We felt they were a bit one-dimensional and really harping on that schlock horror, corny stuff. I think they adopted the ‘goth’ tag rather than the tag adopting them, as it happened for Bauhaus.”

For many of those who slithered through the Batcave and became elevated by the media as icons of the dark side of pop, the title of goth was one taken on very reluctantly. Some bands and artists denied and still deny their status in the subculture.

“At the time we thought it was limiting,” David explains. “There was so much more to the band. We were really into exploring and expanding and we just thought it was a limiting label, so we didn’t like it too much.”

The goth subculture came from aesthetics and philosophies and literary traditions reaching out, linking together in a cumulative genealogy, a goth snowball – changing constantly right up to the present day. At face value, a link between Edgar Allen Poe and Industrial dance music is not one made easily.

“Someone who is into gothic metal doesn’t necessarily have much in common with someone who is into industrial noise – their paths may not cross much,” says Ladouceur. “But at the same time they’re under this big umbrella of gothdom. They’re all children of the same parents.”

From cybergoths to romantic goths to deathrockers and rivetheads, all are offshoots or branches that create a great canopy of goth. One that, at times may obscure its roots – but not for those who have stayed the journey.

“Bauhaus have done several reunion tours, so we’ve seen that fan base grow exponentially,” says David J. “The original spark might be gone, but the essential core remains. The thing that runs through it still is the essential romantic impulse – that dark, romantic impulse. And it’s very attractive as an escape. You create your own identity and I think those individuals who are really into that and fully embrace it… that truly is them.”

And therein lies the appeal and the key to its longevity, for the fledgling goth has so much to draw from and there is enough within it to help forge an identity unique to oneself, while also belonging to a community. Each disciple speaks in his or her own dialect.

But despite its ability to continue and thrive, any ‘ideal’ original scene had to be ephemeral. Certain aspects of being goth became codified, not least by the immediate descendent of the Batcave, The Slimelight club. The club which came to prominence in 1987 defined itself with an exclusion policy against non-goths. Newcomers had to be signed in by an existing member to prove their ‘gothness’ as if such a standard was pre-established and discernible to those ‘in the know’. Though there are exceptions, the idea of a goth scene today where the friendly comprehensiveness of the Batcave still perseveres is a difficult one to picture. And that’s because, in truth, the Batcave was simply a space. Whether goth would have eventually been birthed regardless is up for debate, but it was certainly the right place at the right time.

“I think it is a nice myth about all these people who hung out there, but who knows how it all really went down,” says Ladouceur. ”It’s not like any of them went out and made a record or a song about the Batcave, it’s not quite so direct. From my experience with subculture, you need gathering space for things to hatch. Of course people can do things at home, but it’s when they come together and see other people doing things and they want to one-up them and when fans and come and be apart of it.

“For things that are associated with taboo like sex and death and fetishism, sometimes it’s hard to find that space that could go on for years without getting closed down, so I think there’s a lot to be said for that – that it was a place where people could go.”

“It was the same with punk, where did it really start?” says Nik Fiend. “It was probably more that ‘something was in the air’, you have a number of like-minded people all starting something new and eventually it becomes a ‘movement’ or a ‘genre’. It’s the longevity that’s most important, it’s more rampant now than ever. When we went to the US or Canada or Japan, they would ask about The Batcave – people were intrigued and it’s still being talked about 30 years later!”