Perhaps not as monolithically daunting as an artist like Sun Ra, the back catalogue of The Art Ensemble Of Chicago is still a hefty one. Look past the vast trove of studio albums – with a significant pile of live LPs stacked on top of that – and you’ll still have the solo and extracurricular activities of the group’s five mainstay musicians to explore, not to mention the revolving door of other long-term and short-term members.

It’s a lot to take in.

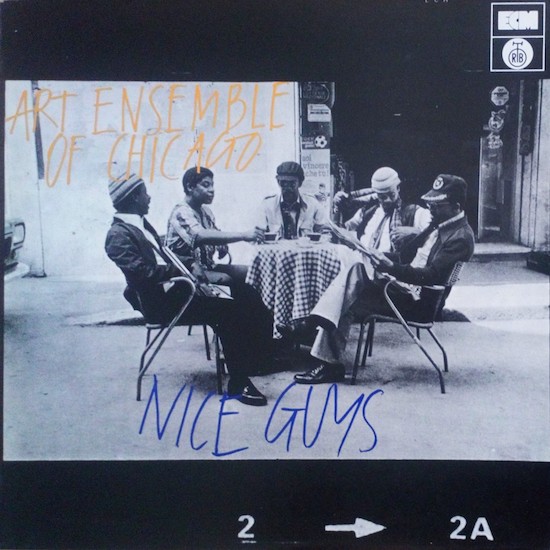

I first encountered the magic of The Art Ensemble through 1979’s Nice Guys, not as fiercely unprecedented as earlier chapters in The Ensemble’s story, but still, an intriguing one. It’s the group’s first album for ECM and like all of their work is beholden to the famous mantra: ‘Great black music – ancient to the future’.

A lot of ground is covered on the record. You can hear them taking in elements of reggae, further exploring their infatuation with ‘little instruments’, and ‘dreaming of the master’ himself Miles Davis. It also marks a juncture of sorts, the end of a five year silence in terms of recorded material and one which ushered in a stellar run of records for music label giants ECM. I’d say this makes it an ideal entry point for the uninitiated.

As the name would suggest, The Art Ensemble Of Chicago formed in formed in that city’s south side during the mid 60s. In their most steady incarnation, they were comprised of five very distinct musical individuals; Roscoe Mitchell, Lester Bowie, Malachi Favors, Don Moye, and Joseph Jarman – who passed away earlier this month after a lifetime dedicated to the opening up of sound.

Now, there’s a myth amongst some that democracy is incompatible with the music group, that a dictator – benevolent perhaps – is necessary, whereas communal creativity means each member must sacrifice their own vision for lesser results. The Art Ensemble undermined this notion constantly. Together, they were able to accentuate the most unique elements of each individual player, the result a music of collective fragments, all members fluent in the art of communicating through the shards.

"The band wouldn’t have survived without us becoming like a cooperative," said founding member Roscoe Mitchell in The Wire. Both Mitchell and other Ensemble members are central figures in the ongoing collective of musicians AACM – Association For The Advancement Of Creative Musicians – a non-profit organisation with the aim to support a network of Chicago-linked misfits whose ideas are too bizarre to fit in with the more conservative leaning jazz clubs.

The AACM actually predates The Art Ensemble and was the community in which the group was birthed. From its 1965 inception through to the present day, AACM can be seen as a directory of avant jazz’s most wayward thinkers – boasting the likes of Muhal Richard Abrams, Anthony Braxton, Nicole Mitchell, and Matana Roberts in their midst. Within this network of non-conformists, Roscoe Mitchell would come across Lester Bowie, Malachi Favors, and Joseph Jarman.

Mitchell’s groundbreaking 1967 debut Sounds was the first release to emerge from AACM, coming the previous year to Jarman’s rule shredder Song For. Both records offer a scene synopsis of sorts, with the essence of jazz remaining while the form gleefully tampered with. Where even free jazz occasionally fell for the curse of doctrine, Mitchell with Sounds, Jarman with Songs For, and later the Ensemble itself remained ever open. This is a group who do not not rigidly stick to avant-garde notions of atonality and anti-rhythm, happy to explore all elements of sound – traditionally ‘musical’ or not.

Their move from conventional jazz sound was aided with an assortment of ‘little instruments’. These ranged from horns and bells through to all manner of strange toys and objects, on top of which they would use their own voices in odd syllabic outbursts, cover their faces in war paint, and utilise a variety of theatrics in the goal of an original art. It’s art full of mischief, but also genuine in its quest to arrive on some alternate spiritual plane.

Whereas their approach would ferment rapidly, sadly the same could not be said for fanbase or finance. This precarious existence prompted The Art Ensemble to move to Europe in the hope to find more open minded ears, and luckily they found them.

Some of The Art Ensemble’s most enduring work emerged from that stint in Europe, no doubt due in part to the adding of drummer Don Moye, but also thanks to properly inviting Jarman to be a member after the tragic loss of two musicians from his prior band.

It was also where they were named by a local promoter, as previously they’d worked under the moniker of The Roscoe Mitchell Art Ensemble. This was key, and marked a final erasure of ownership. As Jarman said, the group was now “a power greater than itself”.

The kinetic force of this newly named ensemble was self evident. Take records like People In Sorrow or Les Stances a Sophie, an album whose absolute scorcher of an opener ‘Themes De Yoyo’ is likely the most righteous fusion of free jazz and funk you’ll ever hear. Defiant horns give way to an omni-directional battering, the rhythm highly taut and then frantically loose.

But for me the crowning jewel of that period is the 1971 album Comme à La Radio, a collaboration with French singer, actor and critical thinker Brigitte Fontaine. Throughout the album, the practices of both Fontaine and The Art Ensemble spar and coalesce in true free-spirit, endless invention found at the very heart of song. It’s one of the great underappreciated records.

Once back in America, this run continued up to 1974’s live album Kabalaba – Fanfare For Warriors, their final studio record until Nice Guys, was released the previous year. Then activities ceased for the group, though members individually guested on forty odd records by other people in the gap. After a period of effective silence for those in need of new Art Ensemble music Nice Guys announced their return.

As previously mentioned, it would be difficult to make a claim for the album as The Art Ensemble of Chicago stretching furthest from tradition. When compared to other jazz from the decade, it’s not as sensually jarring or formally audacious as say, Alice Coltrane’s Universal Consciousness, Don Cherry’s Organic Music Society, or Miles Davis’ On The Corner. But what the record does do is pick up and develop the group’s compositional chops in an audio quality of ever higher definition.

Nice Guys on paper is rather compartmentalised as a record, a succession of relatively short tracks with the reigns of compositional leadership given to a different member on most pieces. Yet remarkably there’s this tremendous sense of both ease and cohesion on the album where you can hear the joy of each player’s whims being explored openly and freely – likely attributed to how long they’d been playing with each other up to that point.

There’s the title track, an onward trudge through seasick swing; ‘Folkus’, an extended, near rhythm-less exploration into tone, a mid-portion hijacked by glistening chimes over gutter-groan sax, while moments earlier its mangled tones are delivered in scattered free-associative jabs.

‘597-59’, meanwhile, barges in all trot and toot, its march swiftly followed by outright calamity. Then it goes back and forth again, and all within the first minute. Throughout this album – as well as the group’s wider career – the expectations that arise at the start of a piece will provide little aid for the listener in terms of guessing where it’ll eventually end up. It’s a sound which endlessly beguiles.

Like all releases in The Art Ensemble’s catalogue, the music’s sources are not strictly that of the avant garde, their approach to these alternate styles one of respect but hardly lofty reverence. You can at times pick up on a kind of twisted trad, derailed dixieland, or take the opener ‘Ja’, where it shifts from a wind and halt of tone to a traditional and rather jaunty reggae sound. It cements the idea that nothing is really off the cards for The Art Ensemble Of Chicago.

All music you come across on the album is presented in a production standard made possible by ECM, and I think this clarity is actually one of the records great attributes. An issue with some prior Art Ensemble recordings – particularly that of some live concerts – is that their poor quality could hold back from The Art Ensemble’s sound, as the structure and intricacies of their music doesn’t benefit from that type of recording. It simply hadn’t been made for those circumstances and the heightened audio reality of a recording like Nice Guys meant that every minuscule sound was granted the most seismic of impact.

All this talk of higher production values and a more succinct, approachable sound may give off misleading ideas about the group’s trajectory. It might make out that their work in the 60s and early 70s comes from the fervour of new life, while what followed was merely a long process of refinement. This is false. The Ensemble were never shackled to one approach, and while Nice Guys invites comparison to to some other studio records, it remains a highly unorthodox work which is later followed by a number of records every bit as atypical as their early material.

From Nice Guys you’re chronologically able to travel backwards, grow accustomed to and find the source of the group’s sound with ease. Or perhaps go forward, and hear them push at the remits in ever altered ways, like on their ECM run with the live record Urban Bushmen, and the studio albums The Third Decade and Full Force. Take for instance ‘Magg Zelma’, the opener of that latter record. It’s a composition in utter turmoil, an oppressive ambience on the dulcimer topped off by the distressed cry of something living being put down, then gargles, then lush liquid reveries, all before a propulsive rhythm comes forth from the din.

Well into the 80s and beyond, The Ensemble were still impossible to pin down. A group possessing a longevity of spirit, despite an unfixed membership. Nice Guys was my first interaction with them and I’m grateful. It’s one of The Ensemble’s most tight, consistent, and satisfying statements, documenting the group’s multifaceted ideas up to that point but with one eye that just keeps pointing forward. Truly ancient. Truly Future.