This feature contains a frank description of suicidal ideation. If you are currently plagued by the idea of serious self-harm please consider speaking to an organisation such as The Samaritans

Unlike the autoimmune disease that almost claimed Ben Watt in 1992, my own horrifying illness wasn’t destined to kill me. Yet it may still have ended my life, had I acted upon the recurring temptation to throw myself from the window of the 28th-floor apartment in which I was living at the time.

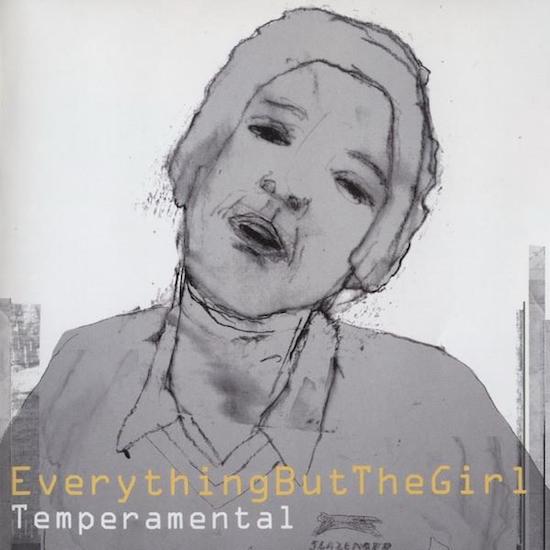

But if I’d done so, I wouldn’t have lived to realise that Everything But The Girl’s 1999 album, Temperamental – of which Watt was the primary architect – may be the most emotionally complex dance long-player of all time. I also would have denied it the chance to play a role in healing me.

Released 20 years ago this week, Temperamental became the final new recording that would bear the name Everything But The Girl. But the band – to whatever extent Watt and partner, Tracey Thorn, ever were a “band” in the conventional sense – had begun flirting with the idea of retirement a year before the album was released. In January 1998, Thorn gave birth to twin daughters, and became so happily immersed in the responsibilities of motherhood that she played an unusually limited role in Temperamental’s creation. In one of her autobiographical books, Bedsit Disco Queen, she writes that “in a sense, I ended up being guest vocalist on someone else’s album.” But nor did this bother her. At least for the time being, she was willing to surrender her executive role in the very group for which her voice had always been the hallmark.

It was, she has often acknowledged, a perverse time to decide to step away from music. Thorn and Watt had been a couple since 1981, and Everything But The Girl [EBTG] their livelihood since 1984 – the year they were swept up from the post punk underground in which they cut their teeth (Watt as a solo artist; Thorn also solo and as a member of the minimalist trio Marine Girls) and into the arms of a major label and the Top 40. Throughout the 80s and into the early 90s, EBTG unselfconsciously fashioned one of the most enigmatic careers of that period. Despite their music always being rooted in melody and traditional songcraft, they had no interest in kowtowing to their audience’s expectations. And so each album was a stylistic curveball that bore little resemblance to what came before – the cosmopolitan jazz of Eden gave way to the Smiths-indebted guitar pop of Love Not Money, which in turn was jettisoned for the grand orchestral balladry of Baby The Stars Shine Bright, and so on. EBTG were successful, but not to the extent their handlers believed they could be. Only when they made the uncharacteristic decision to release a popular cover version as a standalone single (‘I Don’t Want To Talk About It’, originally a number-one for Rod Stewart) did they graze the top of the charts – it rose to number two in 1988.

And then, at a time when their music and their personal lives had become altogether too absent of risk and thrills, all hell broke loose. Thorn and Watt were contemplating how to move forward from the critical and commercial humiliation of 1991’s Worldwide – an album so exceedingly polite that the public felt it impolite to acknowledge its existence — when Watt began exhibiting a host of symptoms that flummoxed every doctor who examined him. He suddenly had asthma that was indifferent to the strongest medications available. And then hot flushes and agonising body pain. Only after he was finally admitted to hospital and surgeons elected to cut him open was the root of the problem discovered: Churg-Strauss Syndrome, a severe inflammatory condition that was essentially causing Watt’s intestines to destroy themselves. He almost died multiple times throughout the weeks that followed, and for the next year his and Thorn’s life together would be lived under an ever-present cloud of post-traumatic anxiety and caution.

When they were ready to be creative again, EBTG’s music acquired an unprecedented degree of guts. Amplified Heart, released in June 1994, found them marrying spare acoustic arrangements (featuring veteran players from Island Records’ folk-rock heyday) with rough-edged programmed beats — a notion of “chill-out” music at least a year before that nebulous genre was given a name. The album’s lyrics and overarching mood betrayed Thorn and Watt’s recent mindset: emotional exhaustion chafing against a barely perceptible determination to fight one’s way toward the light.

At the top of Amplified Heart’s second half is the song ‘Missing’, which was released as a single. In keeping with the chart performance of all of EBTG’s singles since the turn of the decade, it stalled far outside the Top 40. Warner Music, their benefactors for the previous decade, decided this was as successful as the group could ever hope to be again, and duly dropped them. In the U.S., where EBTG were virtually invisible in terms of public profile but still under contract, someone in the dance department of their stateside label, Atlantic Records, commissioned Todd Terry to remix the track. The house DJ and producer listened to the song – a gentle but quietly seething elegy for a vanished lover, underpinned by an insistent four-four beat – and decided it needed nothing more than a dancefloor-ready rhythm track. Beginning in Miami nightclubs and slowly radiating out into the rest of the world, ‘Missing’, in both its remixed and original incarnations, went on to sell three million copies. More than a decade into their career, EBTG had achieved their breakthrough. To borrow a phrase of which Thorn is fond: You couldn’t make it up.

The club-led triumph of ‘Missing’ dovetailed with two other transformative events in EBTG’s trajectory. Massive Attack had invited Thorn to contribute vocals and lyrics to what would become Protection – the album that, alongside Portishead’s Dummy, cemented the mainstream’s perception of trip hop (whether rightly or wrongly). The association imbued EBTG with a halo of credibility and youthfulness not typically gifted to artists well into their thirties. Watt, meanwhile, became enamoured of drum & bass, which was yet to bubble up to the mainstream. Emboldened by ‘Missing’ and their survivors’ tenacity, they decided to bring forward their musical past and fuse it with what they thought to be music’s future.

At a remove of almost a quarter century, it beggars belief how good Walking Wounded still sounds. EBTG’s formal announcement that they were now fully committed to dance music, the 1996 album is a masterpiece of wilfully collided worlds. The inherent qualities of drum & bass and house beats – euphoric and often hysterical in their volume and velocity – create an extraordinary tension with Thorn’s voice, an instrument whose greatest virtue is its understatement, its always sounding seconds away from surrender (to love, to ennui, to life itself). Combined with her and Watt’s melodic instincts, Walking Wounded stayed faithful to the time-honoured notion of “tears on the dancefloor” while existing on something of a cutting edge. An unprecedented number of record-buyers recognised its virtues – it became, by far, the best-selling album EBTG would ever make.

And this was when Thorn began thinking it might be time for her to bow out, to leave the stage and set down roots at home with newborns in her arms.

Left to his own devices in their basement studio while Thorn was upstairs with the twins, Watt set about making Temperamental – the album that would uncannily mirror my own experience of overcoming a brush with oblivion.

Temperamental was the first EBTG album intended as an aesthetic continuation of its predecessor. In short, another dance record, synthesizing the most recent developments of clubland with the duo’s intrinsic song-based approach. But, whether unconsciously or by design, something was slightly different about the songs that Watt (and occasionally Thorn) wrote here. The tug-of-war between swaggering urban rhythms and introspective concerns that defined Walking Wounded now leaned more toward an indefinable, unshakable restlessness. Thorn remarks in her book that Watt’s lyrics are “mostly about going out.” But the protagonists in these songs aren’t going out to be celebratory. They seem to be going out because staying at home means being alone with your thoughts. In going out, your thoughts still follow you, but at least you might find distraction.

The titles of Temperamental’s first two tracks, ‘Five Fathoms’ and ‘Low Tide Of The Night’, equate London nightlife with aquatic imagery – an immersion, something in which to get lost or to drown. “I walk the city late at night,” sings Thorn (acting as surrogate for Watt, who wrote the lyric). The chorus repeats “I just want to love more,” but its tone is ambiguous.

And then, in the song’s bridge, Watt sets out what may be theme of the album:

“The days roll by like thunder, like a storm that’s never breaking

All my time and space compressed in the low pressure of proceedings

And they beat against the sides of my life

Like fists against the sides of my life

And the roads all lead behind me, so I wrap the wheel around me

And I go out.”

My theory is that Temperamental is Watt belatedly reckoning with life in the aftermath of near-death. He was at this point busy as a DJ in his own right, and was often going out without Thorn. Temperamental could be interpreted as the interior monologue of someone obsessively running toward the adult playgrounds that exist outside one’s front door, but who can’t stop thinking of the reasons he feels compelled to do so.

I began relating all too well to this idea in Summer 2016 – almost 17 years after I first heard Temperamental. Little more than half a year previously, in October 2015, I was diagnosed with dystonia, a neurological movement disorder so uncommon that most doctors I subsequently met had never heard of it. This was why my head had begun tremoring and pulling aggressively backward. Specifically, I had cervical dystonia. My manifestation of symptoms, subclassified as retrocollis, is apparently so rare that a specialist told me I was “worthy of study.” The spasms exerted downward pressure onto my spine, and soon I was in constant, excruciating pain that extended from the back of my head, throughout my back and into my hips. A career writer, I could no longer type or handwrite without extreme difficulty. (I knew I was in serious trouble when a potential freelance client asked me to scribble my phone number onto a scrap of paper and I was barely able to do so.)

Within weeks, I had no choice but to stop working. Walking around the block became a Herculean effort. During one of a series of distraught visits to hospital, an emergency nurse, noting my panic, dispensed a pinhead-sized tablet into my hands and told me to dissolve it under my tongue. It helped somewhat, and so I was sent home with a prescription for lorazepam that would lead to addiction and horrifying episodes of tolerance withdrawal.

Unlike most sufferers of dystonia, who at least have the consolation that their symptoms abate when they lie down, mine were aggravated by touch – I began wearing a hooded sweatshirt to bed, to stop getting friction burns on my scalp as my head skidded helplessly across the pillow. I was now averaging, at best, an hour of sleep each night. Profound depression and a degree of madness set in. My sprawling collection of vinyl and CDs – a lifetime’s accumulation and my most prized possession – sat untouched; it meant nothing to me anymore. One morning in early November, I woke up feeling inexplicably nauseous, and the feeling didn’t subside. Between this and the ceaseless physical exertion of my spasms, I began shedding half a kilo per day. I looked on with perverse fascination as my clothes began hanging limply off of my shrinking frame. Coincidentally, I thought more than once about Ben Watt’s sunken post-recovery torso from the cover photo of Amplifed Heart.

Had I met a similar fate as most people who contract dystonia, I would have been disabled for life… however much longer I’d have allowed my life to be. But for reasons I’ll never know, I began coming into remission in Spring 2016, a mere seven months after my head first involuntarily turned while I sat typing at my laptop. I have theories about why I became such a fortunate statistic: early diagnosis; rapid access to a brilliant neuroplasticity specialist, whose treatment methods are based in the notion that the brain can repair itself. I also hold the somewhat controversial opinion that dystonia, at least in my instance, has a psychosomatic component caused by subconscious trauma – it seems unlikely that it was a coincidence that as soon as I stopped catastrophising my situation and accepted the love of the support system that sprung up around me, my own recovery began. At the beginning of March, I could barely walk to the kitchen; at the beginning of April, I walked seven kilometres from my apartment in Vancouver’s Yaletown neighbourhood to English Bay Beach and home again.

I began listening to music as voraciously as I ever had. But something was now very different.

My musical taste had always been fairly diverse, but its focal point since my teenage years had been indie guitar music. In particular, the vulnerable, romantic, melancholy strain that has continued to flow forth from the totemic influences of Orange Juice and The Smiths. (My first book, Popkiss, published within weeks of my dystonia developing, was about this very thing.) Now, I didn’t want to hear that anymore. I didn’t want to hear anything that suggested sadness, no matter if that sadness was meant to be therapeutic or redemptive. I’d looked out of a high-rise window, my face a topographic map of tear-induced rashes, and contemplated the peace I’d acquire after impacting with the pavement below. Sad music, I now decided, was a luxury for people who had never known sadness as I’d recently known it. I wanted uncomplicated, unapologetic joy. And I wanted groove and momentum. I wanted – needed – music that would propel me, because part of my recovery program was to walk as much as I could. And so throughout the ensuing summer, I walked virtually the whole of the city for hours almost every day. I walked until my feet raged in protest. And then I ate my dinner and walked some more.

My new soundtrack, in part: Chic, Shalamar, Curtis Mayfield, Al Green, Chaka Khan, Roni Size, Jam & Lewis productions, compilations of Blue Note rare groove and Trax proto-house and obscure Brazilian funk. None of this music was new to me, but now it wasn’t peripheral. It was the centre of my universe.

Everything But The Girl certainly had never been peripheral. They had been one of my favourite bands, and Tracey Thorn my favourite singer by far, since 1985. But their post-‘Missing’ period hadn’t meant as much to me as the first few years of their career, when their vestigial indie roots were still in evidence. Suddenly, the propulsion and luxuriant textures of Temperamental complemented, and were in sympathy with, my reformed mindset. Yes, in its minor-key melodies and minor-key worldview there was sadness at its core, but the beats surrounding them made the songs sound ultimately triumphant.

And it was my triumph that I needed to ensure remained my focus, because there were fresh memories of unfathomable darkness competing for attention. Like the songs’ narrators, I was habitually going out – not only because it was a mandated part of my recovery process, but because I too needed to not be home. I needed to seek distraction, needed to move forward to keep from falling backward into my thoughts.

Thorn and Watt are still together, but the entity of EBTG ceased to exist not long after Temperamental entered the world. In their notes for its 2015 deluxe reissue, they write that the album is “the sound of a band coming to a natural end,” which I think is informed more by their fractured experience of creating it than its actual contents. While it sold far less than Walking Wounded, and was savaged by some rock-leaning magazines who had tired of indulging the “electronica renaissance” that began a few years before, after 20 years it has aged very well. In the years since my recovery, I’ve explored the length and breadth of dance music as if it were my job, and I can’t point to another album of its kind that so effectively bridges the divide between the deeply communal sound of the dancefloor and the deeply private vocabulary of a mind in trouble.

It was beautiful, what Temperamental did for me in 2016, and still does for me today. I’ll take with me to my grave the memory of listening to ‘The Future Of The Future’ – Temperamental’s final track and, to me, its crown jewel – and shedding happy tears over its gorgeous aural landscape while Thorn sings: “It’s so bright tonight / Do you see those cars, those lights?”

Meanwhile, night was falling over the Vancouver skyline, and I was here, alive and grateful to be experiencing the moment.

Michael White is the author of the Sarah Records biography Popkiss