Every story has a beginning, a middle and an end, but, as contemporary narratives demand, Talk Talk’s has come to be told in reverse, caring little for distractions. There are ‘wannabe’ years and ‘we-made-it’ years, but it opens with the death in 2019 of their inscrutable mastermind, when an unforeseen outburst of respect and affection for singer Mark Hollis rivals tributes to Prince and David Bowie. Unexpectedly, these eulogies dwell not on the conventional success of early endeavours, nor his biggest hits. Instead their focus is his final albums, two with his band, one solo coda, each commercially ill-starred.

Over the years, these latter recordings have been discreetly compartmentalised from Hollis’ and Talk Talk’s youthful product as stylish stars in waiting. In the early 1980s, they’d applied punk’s ‘can-do’ attitude to nascent synthpop, with some material dating back to Hollis’ late 70s band, The Reaction. Though distressed by being marketed as new romantics, they reaped the rewards of these peppy pop triumphs, and until the world mourned Hollis’ loss, these were the songs they still played on the radio.

The twist is that, as everyone now knows, 1988’s Spirit Of Eden and 1991’s Laughing Stock – despite being praised for Talk Talk’s reinvention – had left financial underwriters short-changed. Before the decade was out, their manager was forced to reissue the latter on his own label, and though Hollis doubtless cared little for such details, 1998’s eponymous swansong fared worse. Merely denting the UK’s Top 100, had it not been for Keith Aspden’s Pond Life label once more, it would have been deleted within three years.

With Hollis’ later work suddenly acclaimed far and wide, one could hear a collective gasp: “It wasn’t just me after all!” Naturally, this served as a welcome sentiment, but during the 20-year absence that had followed Mark Hollis, each record had felt like an intimate secret, shared with only a few. Now, with his death, came salvation at last, and therein lies Talk Talk’s legend. Calmly flourishing ever since he vanished, without a word, into the English countryside, this comforting mythology has assigned him an underdog’s role. Talk Talk had played the game as best they could, but fulfilling their paymasters’ demands had left them, and the public, unsatisfied. Only once Hollis called the shots did the group realise their potential.

Or so hindsight insists, whatever anyone thought at the time. To hell with accountability. That these remarkable records, made in remarkable circumstances, could be silently, globally treasured rebuts the market’s interminable short-termism. We celebrate Hollis’ resistance to economic forces, and champion his exploitation of major labels, bequeathing us radical perfection. Great art always wins out in the end.

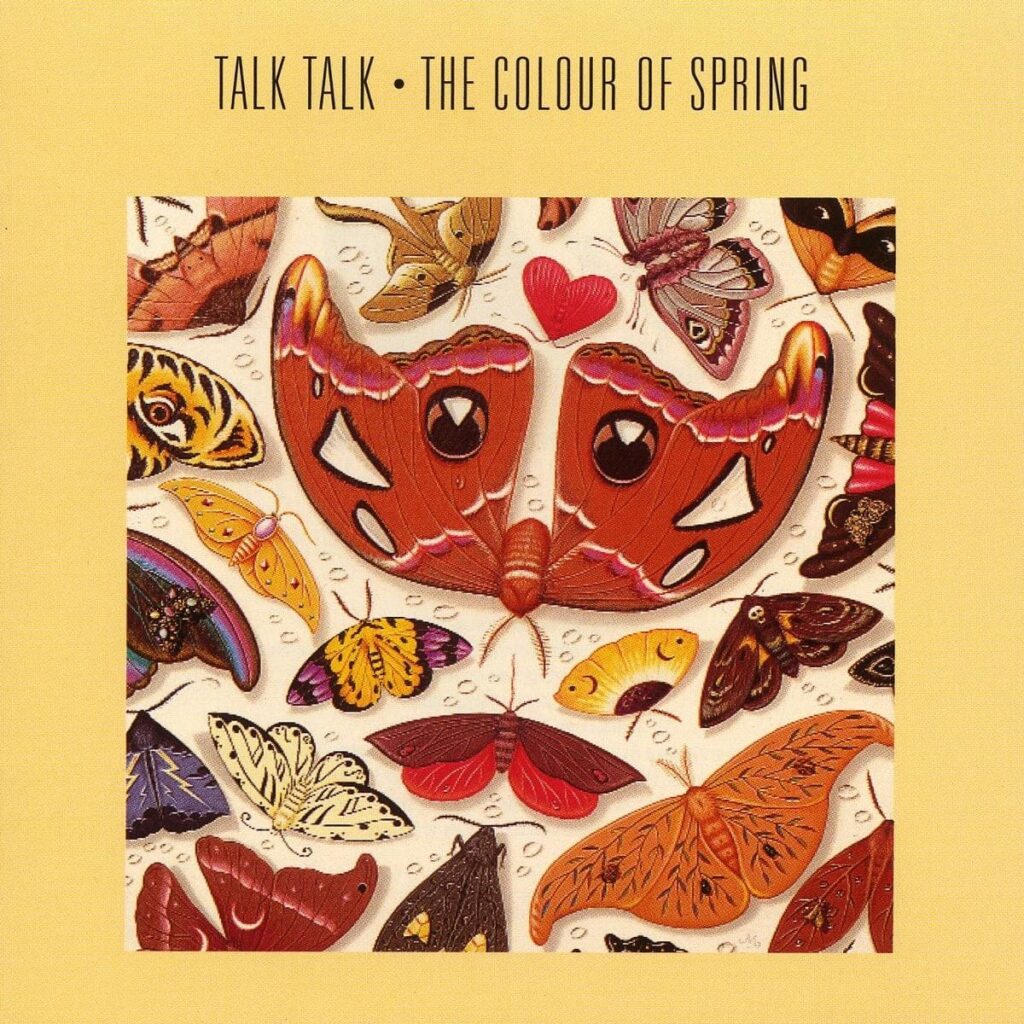

To hell, though, too, with the true story, or, as Hollis puts it on ‘Happiness Is Easy’: “Take good care of what the priests say”. By relegating earlier work to obscurity, this version of events is selective, even specious. He may have cast aspersions on how the band began – “That whole synth side,” he once said, “get it in the bin” – but this belated rush to hail latter accomplishments has bred collateral damage. The Colour Of Spring’s miraculous regeneration is its greatest casualty. Despite its monumental, unknowable gravity, it remains associated with naïve follies.

That epitaphs neglected, at least to a degree, this metamorphic work was likely down to phenomenal sales repudiating contemporary interpretations of Hollis’ intentions. How can we espouse his dogged nature when backers got what they’d stipulated? Even today, ‘Life’s What You Make It’ – prompted by concerns about the album’s uncompromising lack of popular appeal – remains as compelling as Kate Bush’s ‘Running Up That Hill, which provoked it (alongside Tennessee Wiliams’ A Streetcar Named Desire and Booker T. & The M.G.’s ‘Green Onions’.) Similarly irresistibly engrossing is ‘Living In Another World’ (inspired, Hollis claimed, by Jean-Paul Sartre).

Nonetheless, if Hollis proved anything, it was that the conventional path was already too tame. Opener ‘Happiness is Easy’ and the closing ‘Time It’s Time’, not to mention the passionate ‘I Don’t Believe In You’ and plaintive ‘Give It Up’, are awash in startling instrumentation, foreshadowing what later unfolded. Likewise, the fragile ‘Chameleon Day’ and ‘April 5th’ – a paean to his wife, Flick, whom he married during recording – are as spartan and moving as anything he wrote. That Talk Talk gave us hits as well should never be held against them.

These weren’t mere vittles for the great unwashed, rendered by contemporary production choices a pale shadow of Duran Duran. The Colour Of Spring was a masterpiece of resourceful ingenuity, a template for the future. As he signalled on the sublime ‘I Don’t Believe In You’, “I’m trying to leave some self-respect”. With each new record, Hollis further indulged such whims, but here’s where he first rose above both his and his band’s technical, technological limitations. The Colour Of Spring’s only misfortune is to have been overshadowed by all it enabled, a piggy in the middle of a fairy tale bookended by juvenilia and genius.

The Colour Of Spring may be more accessible than what followed but it’s no less intoxicating. To recognise its full significance, however, one must understand how reviled Talk Talk were, at least in their homeland, around its germination. Here, with most of their ‘hits’ anything but, they’d fallen short as pop stars. While media chipped away at their credibility – for the white suits of an early photoshoot (used on the back of 1982’s ‘Talk Talk’ single), then their ascendancy on the continent that gave us Nena and Falco – ‘Such A Shame’ and ‘It’s My Life’ missed the Top 40, and only ‘Today’ pierced the Top 20. “They’re the Duran Spandau Leaguoo,” Lemmy chuckled to Record Mirror, unjustly echoing the day’s received wisdom. The band had become a punchline.

There was confusion, too, in matching their highbrow intentions with their ludicrous behaviour. Notorious for their practical jokes, “We had something called ‘the wet room’,” drummer Lee Harris recalled in 2006, “where we’d set up a dressing room, invite another band in after the show and then soak ’em.” Additionally, when not baffling press with flamboyant references to Debussy and Delius, they were endorsing impressionists in other fields. “Russ Abbot,” Hollis claimed, “is a genius!”

This, at least, was if Hollis was not already berating journalists. “I’ve told you about eight times before,” he lectured NME’s Neil Taylor, right on the brink of their third album. “All Talk Talk have done is make three very fine albums with a gap of two years inbetween each. We’ve made each album different from the last, and we’ve based all our albums upon our songwriting strength. So don’t give me no Spandau Ballet shit, success shit, or image shit. Our image is our music.” Taylor’s diagnosis – “What a prat!” – was succinct.

He joined others, like Smash Hits’ Dave Rimmer, who, four years before, had declared Hollis “an abrasive character”. Merited or not, such coverage included the kind of invective that made the music press notorious. “Oh, the pain of being a member of Talk Talk!” Smash Hits’ David Hepworth remarked wryly in 1983. “The starched shirts, the meaningful expressions, the dry ice, the anguish, the adenoids, not to mention the snide reviews!” And boy, could they be snide. In 1984, Record Mirror called them “crushingly, excruciatingly average… Duran without the lust for success, Roxy without the sloe-eyed style, Tears For Fears without the suicidal touch”.

Hollis took the media about as seriously as they took him, but that didn’t lessen his urge to defy them. Nor did over a million sales of It’s My Life worldwide. “That was the album that put us in a position to become more insular,” he told Vox around Laughing Stock, “because we made it in England with no contact from the record company. That LP didn’t really do anything here, whereas in Europe it did really well. I’d got the freedom I wanted.”

Earning a commensurate freedom, The Colour Of Spring let loose in the studio – for a whole year! – a man who once, during American promotion, deconstructed a New York sandwich by removing most of its contents until he considered it suitably ‘English’. “We had as much time as we wanted to make it,” he confirmed to Melody Maker. “We could use whatever people we wanted as long as they agreed to play on it.”

Hollis began by hiring a producer first recommended to remix It’s My Life. Classically trained, Tim Friese-Greene had worked with Tight Fit, Blue Zoo and The Nolans, so the choice was either a concession to EMI or, like so much ahead, magically intuitive. Regardless, once this ally earned co-writing credits on both their second album’s title track and ‘Dum Dum Girl’, there was no going back. Not that Hollis was in any rush.

The duo spent 1985’s first four months locked down, working up songs, 12 hours a day, six days a week, with Harris and bassist Paul Webb sidelined. Setting a precedent for their famously time-consuming process, they worked with the same care as they would two years later, largely by trial and error. For Hollis, whose concepts could be ineloquently expressed, Friese-Greene was a necessary facilitator. “Speech gets harder,” the frontman acknowledged on ‘Living In Another World’. “There’s no sense in writing.”

Blessed with insight (and presumably patience), Friese-Greene appreciated Hollis’ customs as others embrace Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies, translating impulsive inclinations into recorded reality. But these schemes weren’t as militant as Hollis later claimed when he dismissed synths as “an economic measure. Beyond that, I absolutely hate them.” This gave the impression they were gone for good. Hollis was more pragmatic.

“The only good thing about them,” he’d continued, “was they gave you large areas of sound to work with.” So synths were retained, with rhythms a priority, shaped on a Fairlight II in the influential aftermath of an African trip that Friese-Greene had recently enjoyed. In addition, the correct amps, as well as a fuzz pedal, ensured a Jupiter-8 and a Prophet-5 provided some putative ‘guitar’ solos. Nonetheless, their prominence was substantially diminished, revealing a newfound humanity.

Previously, emotional impact had depended chiefly on Hollis’ voice. Now they expanded their range. “From the place that I stand,” as ‘Give It Up’ would formulate it, “to the land that is openly free”. Before long they were aided by Traffic’s Steve Winwood, whose organ immortalised ‘Life’s What You Make It’, and The Pretenders’ guitarist, Robbie McIntosh, who, in keeping with Hollis’ broadening horizons, brought his dobro with him.

Mark Feltham also swung by, his harmonica embellishing ‘Living In Another World’s noble drama as it would later shatter ‘The Rainbow’s tranquillity when he returned for Spirit Of Eden. Present too was Danny Thompson, who would also return, and The Average White Band’s Alan Gorrie, their bass lines supplanting some of Webb’s contributions, just as Harris’ drum tracks would sometimes be eased out for the core team’s programmed efforts.

Then there was keyboardist Ian Curnow, an It’s My Life holdover who, once he’d finished touring this new album, would become Stock, Aitken and Waterman’s guy. Though the incident is often linked with later records, it was Curnow’s hand that was gaffer taped, forcing him to play with two fingers and a thumb. But it’s no coincidence the anecdote’s origins are clouded. As harpist Ganyor Sadler confirmed, this was where Hollis and Friese-Greene established their methods. Called in to contribute to ‘Give It Up’, she received, in line with future practise, not one word of direction.

Underlining the record’s dynamic qualities, Hammonds and mellotrons, woodwind and percussion, melodicas, Kurzweil and Variophon – not to mention guitars, choirs, even recorders – ensured a textured, organic feel. That this is where Hollis’ breakthrough transpired, he spelled out in 1991. “I do understand why some people say these last two albums are a complete departure,” he told Melody Maker, “but for me I can trace the idea right back to Colour Of Spring and beyond.”

Helpfully, these hired hands provided a credible authenticity which Hollis had always craved. No longer depending on machines for expression, settling for their frustrating best, now he strove for perfection, uncovering beauty in man’s fallibility. With reverence for his heroes unquestionably sincere, this time he swore Béla Bartók (“a great geezer”) could be detected in arrangements, and the notion that Satie left a mark on ‘Chameleon Day’ is no more implausible.

It’s not too far-fetched, either, to suggest Carl Orff coloured the Ambrosia Choir’s role in ‘Time It’s Time’s grand finale. In Hollis’ rejuvenated voice, too, there were clearer indications of his declared love for soul, not least Otis Redding. There’s a corresponding pain in his heart in, most notably, ‘I Don’t Believe In You’s repeated melodic descent and his phrasing of pivotal lyrics:

“Any way you say it

The charade goes on

But your eyes won’t see it

It’s the same old song

‘I don’t believe you…’”

Far from being recognised as an attribute, as it would be later, Hollis’ receptivity (bred by Ed, his late punk rock brother) was mocked as ostentatious namedropping. Despite his sunglasses, this pretentious, jug-eared Tottenham poser didn’t fool anyone, and his blend of the mainstream and avant-garde wasn’t anything so grand as ‘post rock’. At most it was ‘post prog’ – a contemptuous term here, as worthless as for Spirit Of Eden or Laughing Stock – when all three, in essence, were pretty much ‘post everything’.

Indeed, in a brutal NME review, The Colour Of Spring was mistaken for “having all been done before by The Yeses and The Moody Blues and The Tulls and all those crappy dinosaur groups we can all do without being reminded of, thank you.” The knives came out elsewhere too. “An impressive record,” Smash Hits conceded, “but not something to listen to if you’re down.” Meanwhile Record Mirror contended, “Talk Talk are probably the most boring band in the world.” Number One punched lower still: “Not even as famous as Alvin Stardust.”

Yet ‘Life’s What You Make It’ emerged fully-formed, like one of the butterflies from the sleeve art, to score a worldwide hit. Testament, furthermore, to the album’s abundance was how its eleventh-hour appearance consigned to its B-side the extraordinary ‘It’s Getting Late In The Evening’, as pretty as anything on Radiohead’s A Moon Shaped Pool. Even bolder was how this upheaval came on the heels of the artifice of Talk Talk’s first two albums. With a season of their invention, the winds were changing. The Colour Of Spring became their biggest seller.

In limiting its value to where it led, we damn The Colour Of Spring with faint praise. Itself a vital manifesto, it’s always deserved its own raptures, and not just for familiar songs. Bathed in compassion, merging Hollis’ many enthusiasms – whether in its big hit’s accepting optimism or ‘April 5th’s haunting hush – it’s both extravagant revision of earlier pursuits and unmistakable confirmation of his ambitions. Like its successors, its gift is to conjure grief and euphoria from the most unlikely sources.

Thus, children from Barbara Speake’s Stage School lend earnest innocence to ‘Happiness Is Easy’s unhappy counsel as a choir defined Spirit Of Eden’s ‘I Believe In You’. Where it was a one note Variophon solo on Laughing Stock’s ‘After The Flood’, here it’s ‘Time It’s Time’s climactic recorders. Even the teasingly anodyne hum of ‘Myrrhman’s amplifiers, with which that latter album starts, bears comparison with the barely-there ‘Chameleon Day’.

And that ethereal rush punctuating ‘I Don’t Believe In You’s opening lines? It’s spit blown from a mouthpiece. One of two signs, the other a mere squeak, to survive from a brass section’s session, it’s also another indication of a rapidly developed but abiding methodology, eventually so ruthless engineer Phill Brown would erase 80% of Laughing Stock’s recordings at Hollis’ daily behest. Now firmly a stock element of Talk Talk’s legend, it was established on The Colour Of Spring.

Contrived as much from improvisation as refinement, Talk Talk’s remodelling, on the first of what would become three remarkable albums, is as risky a step as Hollis would take. In, however, that “self-respect” he’d intended to leave us lay crafted, collective art. Painstakingly, if happily not in the peculiar manner of his peculiar sandwich, its ingredients had been assembled, then deconstructed, and afterwards gratifyingly rearranged. Its hits weren’t concessions, nor its mysteries indulgence. The Colour Of Spring – instinctive, meticulous, no mere middle man – was exactly what Hollis wanted.

“I work primarily because it pleases me,” he warned NME’s Neil Taylor on the same day he harangued him, presumably with similar impatience. “If people interpret that as arrogance, then so be it. I’ve made an album that is exactly how I want it. That album is now being released. I’ve got all I want out of Talk Talk and nothing, nothing else matters.”

End of story.