“This was London in the early 90s, hugely different from the popular ‘Cool Britannia’ revisionist myth that media hindsight has over-simplistically projected on that whole decade. It felt like the first few years at least were a hangover from the eighties: John Major’s irrelevant, dreary, Tory world of unemployment and cut price lager and crap boy bands”

Brett Anderson, Coal Black Mornings.

If the past is a foreign country then it figures that so many of us cling to stereotypes and dispense with nuance. The 90s of the imagination is awash with New Labour and the Spice Girls and crowds united in grief over the death of Princess Diana, or places them at Knebworth drunkenly chanting every last infernal word of ‘Wonderwall’. Media also plays its part in reconfiguring our memories once the narrative is established, which makes it more difficult to remember how things were before Britain got its swagger on. Suede are now regarded by pop historians as the main catalyst for the Britpop movement, but while their debut album could be described as self-confident, it was anything but celebratory about the times it was emerging in. Loaded and ‘Cigarettes And Alcohol’ and ‘Caught By The Fuzz’ and Blur’s ironic ode to 18-30s culture, ‘Girls And Boys’, were a year away. Suede felt weighty and maybe took itself a little too seriously, like a chiaroscuro kitchen sink drama with added narcotics and wayward sexuality directed by Derek Jarman.

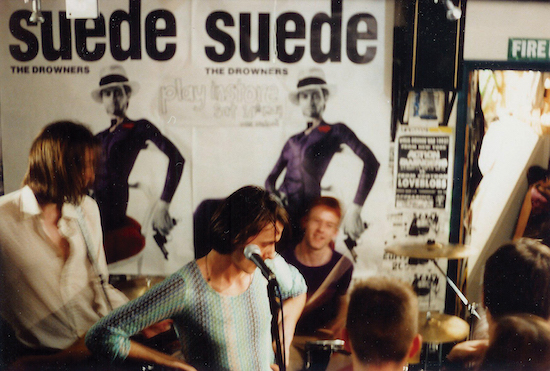

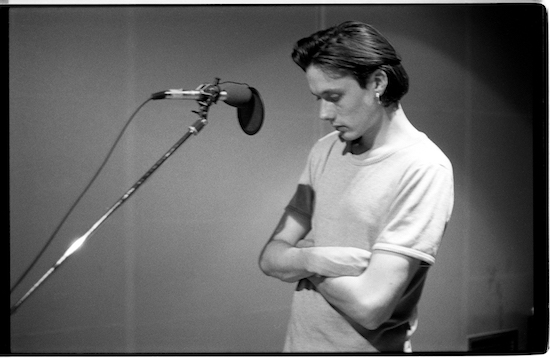

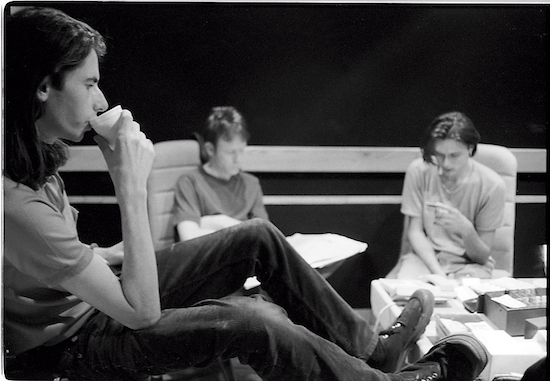

Suede seemed to come from nowhere in 1993, but obviously that wasn’t the case. Brett Anderson and bassist Mat Osman had come from the suburban anonymity of Haywards Heath, and they’d been flogging their pantomime horse in the capital for quite some time before an astounding transformation seemed to occur overnight (coinciding with the exit of Justine Frischmann, who went on to form Elastica and reap similar success on her own terms). Snarling and yelping and mincing in the Top Of The Pops studio in a shirt knotted above the midriff, Brett Anderson was immediately adored and reviled in equal measure, a provocateur who brought much relief to a music press that’d had to feign excitement about bands like Kingmaker for a few barren years. And grunge of course – Suede were an antidote to the self-loathing and anti-fashion of American rock which seemed to underscore their lack of shame about being British.

In his autobiography Coal Black Mornings Anderson maintains that he was “documenting Britishness” all along, and it’s a claim that stands up: “The feeling of ‘Britishness’ that we were developing in our words and in our music and in our style was something exciting that we felt we had stumbled upon, and as such it felt brave and raw and beautifully out of step.” Contemporaries Pulp were doing something similar but weren’t attracting much attention at that time, and of course the Pet Shop Boys had already projected a Cowardian Englishness onto the pop landscape which had influenced Suede. When Bernard Butler answered Brett and Mat’s ad for musicians in NME, the guitarist recalled his interest had been piqued by the diversity of the influences – the Smiths, the Pet Shop Boys, Lloyd Cole and the Commotions – which perhaps don’t look as variegated in the internet age as they might have when music fans were more tribal.

At another point in the book, Brett notes: “The point was to reflect the world that I saw around me and that world just happened to be Britain: a cheapened, failed world that had nothing to do with the laddish, jingoistic and frankly patronising interpretation that would follow”. Blur’s edgy sense of irony raised eyebrows a few months after Suede was released when they posed for the questionable “British Image 1” photoshoot with photographer Paul Spencer, featuring Damon in skinhead attire handling a dog. In the context of the moment it could have been construed as flirting with fascism, especially after Morrissey had brazenly brandished a Union Jack at Madstock in Finsbury Park the year before. Right wing imagery of any kind was anathema in alternative rock and the music press was hypersensitive to it. Suede would inadvertently play a part in changing that perception.

The notorious Select cover with Brett mounted on the national flag with the indefensibly xenophobic “Yanks Go Home!” strapline certainly caught the eye when it appeared in newsstands. It’s reasonable to suggest it’s where the patriotic bombast of Britpop all began, and yet the bands being championed within were far more diffident about what it meant to be British. “I don’t think there’s anything great about Britain as such,” said Luke Haines of the Auteurs. “I don’t have any great feelings of love towards this country. And I particularly hate all this kitsch retrospective stuff about Carry On films and the like, which were definitely not great. There’s not a lot to be patriotic about in a country that’s put up with the Tories for 14 years.” Jarvis Cocker from Pulp spoke of being ashamed of “hooligans: leftover from the days of Empire. People who really do believe that we rule the world or ought to. People who go to other countries and think it’s OK to be rude to the people there.” Lawrence from Felt meanwhile noted that the Union Jack was “just a flag like any other flag, a piece of cloth you hoist up a poll when you’ve won a war”, and St Etienne’s Bob Stanley declared, “I prefer France myself.”

The concept for the magazine campaign had come from Stuart Maconie, who’d recently jumped ship from NME, partly because he was tired of all the grunge coverage. Select’s cover feature was designed as a riposte to Uncle Sam, although not everyone was happy with the layout. “Suede, while enjoying the acclaim and publicity, were peeved with me, perhaps understandably, at being associated with a flag that at that point was seen as the preserve of the far-right,” wrote Maconie in The Mirror in 2014. “But within a few years, it was everywhere, from Noel Gallagher’s guitar to Geri Halliwell’s mini-dress.” Maconie justified it all by saying what came after was “about confidence in being British, a celebration of British life and a new-found love of our past, rather than slavish worship of America.” Brett for his part was happy to go along with the yank bashing: “I still don’t understand why people dress like that. Why English bands persist in Americanising themselves. I don’t understand why American music has to be so military and aggressive. Look at Henry Rollins; he’s like a Sergeant Major or something."

In the same breath, Brett said Suede’s Englishness had been “cartoonised” by others, though with his Bowie yelp and lines like “she’s a luver-ly little numb-bah!”, he was consciously aligning the band with a lineage that went back to music hall via the Sex Pistols and Anthony Newley. There’s a Victorian burlesque naughtiness about the record with a bit of the Dickensian urchin and Steptoe And Son thrown in along the way. The Libertines, with all their talk of Albion, followed the same seam successfully a decade later, which unfortunately gave rise to crack skiffle. Suede documents a kind of romanticised squalor, conflating glamour and poverty & love and poison until they meant the same thing. In a year when a film as asinine as Indecent Proposal supposedly got everyone talking, Suede’s version of sexy was all about jumping bones in council homes (‘Animal Nitrate’), implied gay incest (‘The Drowners’) and infatuation with prostitutes (‘Metal Mickey’).

‘So Young’ bursts forth with a now familiar shuffling drum beat, a wild harmonic, a burst of feedback and a shriek from Anderson, and within the space of three-and-a-half thrilling minutes he’s unapologetically entreatied the listener in falsetto to “chase the dragon” and “scare the skies with tiger’s eyes”. Songs blatantly about heroin didn’t normally reach no.22 in the charts, and they probably still don’t. ‘Animal Nitrate’ is a titular pun on poppers which recounts formative gay sex encounters with a Mike Leigh grittiness and a carnivalesque instrumental led by Butler that’s as thrilling now on the 5,000th listen as it was the first time I heard it. That one got to no.3 in the charts, which was absolutely unheard of for an indie band at the time. ‘Sleeping Pills’ with its “sweet FA to do today” infers an ennui so bad that suicidal thoughts abound. And ‘She’s Not Dead’ recounts the true story of Brett’s aunt, who died from exhaust fumes in a sexual suicide pact in the backseat of a car (“she’s fucking with a slip of a man while the engine ran”). It wasn’t for the fainthearted or future fans of Onka’s Big Moka.

Such confrontational lyrics about having it off had been absent from guitar music for some time, especially in scenes like C86. Shambling outfits such as Talulah Gosh seemed almost afraid of sexual identity and made their natural heirs Belle and Sebastian look like The Doors. The Jesus And Mary Chain and Primal Scream weren’t interesting in scoring with anyone, they were just interested in scoring, and the Wedding Present were too embittered, blokey and uptight to give the impression any of them were hard at it (Gedge is far sexier now than he ever was then). With the backdrop of AIDS and the very real possibility you could get infected at the forefront of most young minds, it was perhaps understandable. The The’s sometimes shocking and libidinal Infected was a rare case of an indie record that smelt a bit sexy, but it was also called Infected (even Prince, a proper popstar synonymous with sexy, was singing about a “big disease with a little name” on ‘Sign O’ The Times’). And Morrissey’s declaration of chastity didn’t damped the swagger of his band The Smiths, but it wasn’t a sexy swagger. By the time Suede showed up, more was known about HIV and how to prevent it, but Suede’s hypersexuality tracks like ‘My Insatiable One’ was still a surprise. It was even more of a surprise when Morrissey covered it.

Suede really did bring sexy back to white guitar rock, and not in a straight or misogynist or objectifying way like, say, the Rolling Stones. Some might point out the fact Brett’s experimentation with gay sex only went as far in reality as being playful with his pronouns, though it still gave empowerment to many and moved the conversation on (it stands at no.27 in Attitude’s Top 50 Gay Albums of All Time). What’s more, it opened up a glorious portal that, via songs like ‘The Drowners’ and ‘Metal Mickey’, could transport you back to the heady glory of glitter rock. There were no three-day weeks or energy cuts, but it felt just as shit to be alive in 1993 as it did in 1973. Like the creme of early glam rock, and almost as a reaction to the coiffured prissiness of American hair metal, Suede brought with them a riot of drug fuelled escapism, and celebrated the bad teeth and the deviant sexuality, the androgynous pop and the glorious failures that make us proud to be British. It’s just a shame somebody brought along a Union Jack.

Suede’s debut album has been reissued in a 25th Anniversary Silver Edition. Brett Anderson’s autobiography is out now