Dominating the music news in 1984 was the early passing of one Black American master and the fullest arrival of another. On 1 April that year in Central Los Angeles, Marvin Gaye Jr was fatally shot following an altercation with his father, the highly complicated Christian pastor Marvin Gay Sr. The soul star died just one day shy of his forty-fifth birthday. As spring turned to summer, Prince – already riding high from the belated attention generated by his 1999 album – released Purple Rain, which detonated as a single, album and box office phenomenon. It was a generational changing of the guards, the type that every decade seems to generate just before the halfway point.

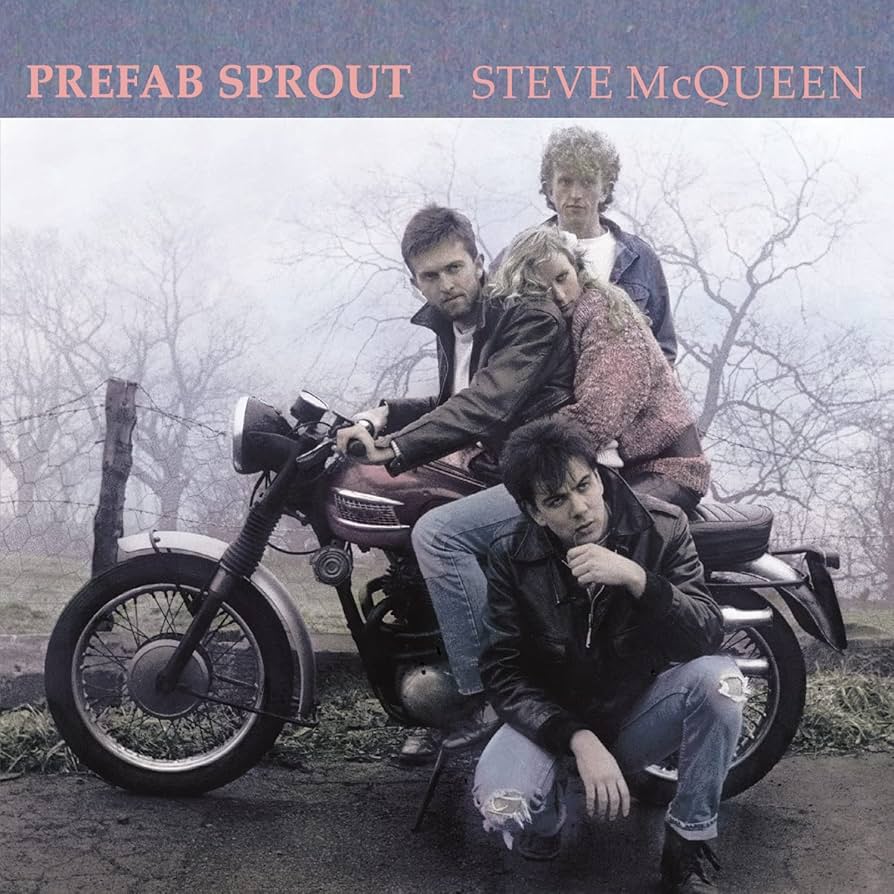

These were both events that would impact on Steve McQueen, the 1985 album by the North East English four piece Prefab Sprout. Neither wholly the work of its sole songwriter Paddy McAloon nor its producer Thomas Dolby, Steve McQueen was a separate third thing: a complex pop masterpiece drawn from a shared imagination between two men who had met as strangers for the first time just weeks before its creation.

Patrick Joseph McAloon was born in the County Durham village of Witton Gilbert in 1957. Younger brother Martin came four years later. Like many other sensitive and bright first generation Irish immigrants in England, the infant Paddy Joe was an obvious fit for the clergy. For seven years in the late 1960s and early 70s, he studied at Durham’s Ushaw College, a Roman Catholic seminary. He could have become a priest had another divine calling not intervened. Paddy had always liked music – in fact, he and Martin had thrashed out naive garage rock as kids under the unlikely moniker of Prefab Sprout – but the musical revolutions of 1977 came calling.

“In 1977 I got a copy of Aja by Steely Dan,” McAloon told the German publication Musikexpress in 2009. “And no one in the world was gonna tell me that was anything other than witty, sublime music making.” Sure, punk was fine, but Donald Fagan and Walter Becker’s hipster-literate vocab, crystalline production values and jazz-influenced songwriting became the blueprint for McAloon’s own. He broke the news to his folks that he had found a different altar to worship at, enrolled on a polytechnic English Lit course, and picked up the Prefab Sprout idea with renewed focus. That year, Paddy and Martin began playing the pubs of Newcastle and Durham. At least four songs that would form the backbone of the eventual Steve McQueen LP date from this period – ‘Hallelujah’, ‘Goodbye Lucille #1’, ‘Faron Young’ and ‘Bonnie’. No recordings survive of this late 1970s iteration, but McAloon would later refer to it as “the Platonic ideal” of what he wanted to achieve with the Steve McQueen project.

But if Paddy McAloon was attempting to travel back in time towards something, then Thomas Dolby was heading to the future. Thomas Robertson was born in 1958 to a prosperous British academic family. His father, Martin Robertson, was a celebrated classical scholar (his 1975 A History Of Greek Art remains a set text on the subject) and so was his father before him. The boy Robertson had been expected to join the family trade, and was educated expensively at Abingdon (where Radiohead would later form) on that proviso.

That was until two things changed everything around his nineteenth birthday. The first was Robertson acquiring a Powertran Transcendent 2000 synthesiser that he says he found poking out of a skip behind a music equipment shop. The second was catching a 1977 performance by Throbbing Gristle (almost certainly, based on the information in Dolby’s memoir, the December performance captured on Industrial’s At The Rat Club The Valentino Rooms cassette.)

Robertson became hooked on punk’s weirdo fringes. He hustled his way into live mixing jobs for The Fall and Gang of Four, began modelling himself on Brian Eno, and became a besotted XTC devotee, whose nervy eccentricity and clattering experimentalism became the blueprint for his own songwriting. With an eye on a recording career, Robertson quickly became Dolby: ostensibly to avoid confusion with Tom Robinson, but also savvily branding himself as synonymous with audio innovation. After a few false starts – helping form a new wave band Bruce Woolley and the Camera Club, then scoring a top 5 single and Top Of The Pops appearance with Lena Lovich – Dolby signed with EMI Records as a solo artist in 1981.

The Golden Age Of Wireless, Dolby’s 1982 debut, sold modestly, but a standalone October single ‘She Blinded Me With Science’ became a transatlantic hit thanks to a memorable novelty cameo by the popular English nutritional scientist Magnus Pyke and an innovative, MTV-ready promo video. With the money from his hit, Dolby bought the ultimate accessory for any self-respecting 1980s futurist: the Fairlight CMI.

Australian engineers Kim Ryrie and Peter Vogel had been developing their revolutionary synthesiser since the mid 1970s. It arrived on the market in 1979, demonstrated for British viewers on Tomorrow’s World the following March. “For the first time, real sounds could be digitally recorded, processed and played back as notes and chords on a musical keyboard,” wrote Dolby in his 2016 memoir. “The genius of the Fairlight was that unlike most new instruments developed by musicians, its user interface was not based on a recognizable metaphor: it was a truly original instrument.” Costing £30,000, the synthesiser was more valuable than Dolby’s Fulham flat.

But events overtook the artist. 1984’s follow up album The Flat Earth is an interesting safari across various hi-tech 1980s sounds – occasionally, as on its title track, touching the sublime – but it was not the success that EMI had hoped for. Dolby began to suffer from writer’s block, not helped by the shock death of his mother Theodosia Cecil Robertson that summer. In his memoir, Dolby recounts long days at the Fairlight, summoning zilch. And then, when he was invited to appear on Radio 1’s weekly Round Table, something changed. He heard bright piano chords, a strummed acoustic guitar, harmonica, and a song about Judas, Mexico and a whiskey priest. What was this?

After signing with Kitchenware Records, a Newcastle independent label run by Keith Armstrong from the top floor of a Newcastle council flat (“To me,” said Armstrong in 2007 to Record Collector, “Prefab Sprout were Steely Dan”), McAloon had a bright idea. He would junk all of the band’s tour-hardened material, and write a debut from scratch. The resulting album Swoon (an anagram of Songs Written Out Of Necessity), has its moments but is overstuffed. Kitchenware took Prefab Sprout to CBS, who signed them through the independent for an eight album deal, largely at the indulgence of executive (and former Spencer Davis Group member and Sparks producer) Muff Winwood. ‘Don’t Sing’ was the album’s lead single.

“I’d never heard anything like it,” Dolby told The Guardian in 2020. “Paddy’s ideas seemed detached from everything except maybe a mid-20th-century American novel. The next thing I knew their manager invited me up to their old rectory in Consett.” Paddy spent the afternoon playing Dolby about forty songs that he had amassed over the years, largely drawn from their late 1970s period. Dolby recorded them to cassette and took notes. On the train back to London, Dolby drew up a list of the twelve songs that he would personally like to record. Both men, up to that point in 1984, had made interesting but flawed work. Each was suddenly about to galvanise the other.

In Autumn, Thomas Dolby convened Prefab Sprout to rehearse at Olympia Studios in West London. Already, the producer was taking an unusually hands-on approach to his brief, rehearsing on piano and synthesisers with the band and bringing in an additional guitarist, Kevin Armstrong. “We were trying to make a record like Thriller with Thomas Dolby in England,” remembered Armstrong in 2007. “In your mind, you’re in LA with Quincy Jones.”

At first, Martin McAloon couldn’t understand why they were going over old aground. “We’d been playing them since 1976, we wouldn’t have chosen them,” he told Record Collector in 2007. “But he made them breathe and added space to them.”

These were McAloon’s songs, but of Dolby’s choosing and done Dolby’s way. Dolby began noticing unusual things about the band’s methods, like how Martin worked out his increasingly knotty bass parts around the lowest notes that he could see his brother’s hand playing – not at all the same thing as the root note familiar to bassists – or how harmonies were established not by group singing but by Paddy writing down notes on a lyric sheet for multi-instrumentalist Wendy Smith to learn by singing against a keyboard. What if these outlier tendencies could be brought to the fore? Drummer Neil Conti remembers a “tense start” when Doly wanted him to play like a drum machine, but Conti – who came from a jazz, funk and calypso background – held his nerve. After rehearsals, the band and producer moved to Marcus Recording Studios in Bayswater to record the album.

The first sounds that you hear on Steve McQueen are twanging, rockabilly guitars. ‘Faron Young’, titled after the Louisiana country singer and referencing his 1971 hit ‘It’s Four In The Morning’, is a relatively anomalous start to the album, a convivial but weightless country rock track complete with a hoedown banjo part programmed by Dolby on the Fairlight. (The Truckin’ mix, available on most reissues, is bolder.)

Then the tempo drops, and this strange album really begins to speak. There’s a pre-Swoon demo of ‘Bonny’ that helps unpick exactly what Dolby achieved with Steve McQueen. Scratchy and melodically repetitive, you can sympathise with the band who discarded it as juvenalia. But Thomas Dolby strips it to bare parts – in this case, gossamer thin acoustic guitar and McAloon’s now calmer and conversational vocal, offset by haunted, windswept electronics – before blowing the production up to a peak.

‘Appetite’ was one of the most recent songs written for the album, penned in the summer of 1984 and stacked full of gorgeous McAloon lines – a young mother “wishing she could call him Heartache / but it’s not a boy’s name” – around a 24-carat chorus. In interviews, McAloon reserved special praise for Dolby’s programming on that track, and the sophisticated, Quincy Jones-style drum and string counterpoint underneath it all. More than this, Dolby samples and manipulates Wendy Smith’s breathy backing vocals through the Fairlight, doubling them up with twinkling keyboards to produce a vocal effect that is the signature of both ‘Appetite’ and ‘When Love Breaks Down’. A defining sonic feature of the album, its only precedent is 10CC’s vocal tape loop experiments on ‘I’m Not In Love’ a decade previously.

Paddy McAloon remembers writing ‘When Love Breaks Down’ as an attempt to get out of his own way, writing with a guitar but also a synthesiser on his knee. “It all came pretty quickly in one night,” he explained in a 1986 interview to Chris Heath, describing the words coming out as though singing “an old hymn or a folk tune.”

CBS had already sent him to record a version of it to be a single with former Cure producer Phil Thornalley before the band had met Dolby. But it tanked. The album version is partially re-recorded and radically remixed by Dolby. It’s a luxurious arrangement with ethereal sampled voices, grand piano, funk bass, McAloon’s crisp Stratocaster plugged directly into the mixing desk offset by Armstrong’s meatier Les Paul fanfares. After this, ‘Goodbye Lucille #1’ spends much of its runtime incanting the name Johnny like a mantra. Like any good mantra, do it long enough and it becomes transcendent: the final minute of the track is pure fireworks.

A fair criticism of Steve McQueen is that it’s wildly frontloaded, its best work dominating the first side. This is true, but spend time with its second side and a more subtle and impressionistic work takes shape. Take ‘Blueberry Pies’, a romantic drama in miniature, or the fizzing, celestial soul finale of ‘When The Angels’. “I wanted to talk about somebody dying young with a wonderful gift,” said McAloon to Melody Maker in 1985, who spoke about wanting to write a tribute to Marvin Gaye that was not “sombre and serious” like that year’s Commodores hit ‘Nightshift’. McAloon had a bit that he liked to do for music journalists where he declared his common cause with giants of show tune like Richard Rogers or Stephen Sondheim. You can hear some of this in ‘Hallelulah’s reference to “Georgie” Gershwin, or the outright eccentric ‘Horsin’ Around’.

This is what’s so interesting about Steve McQueen. It’s remembered as an indie record, but if so it’s a very odd one, because one of its chief architects was trying to write for Broadway, the other attempting to turn in a work of pristine Los Angeles hi-fidelity production. But in that push and pull, it reveals a path not taken, one where British indie might have become more modern and sensual rather than nostalgic and obvious. How much better could British indie music still be if people dared to form these against type pairings?

Steve McQueen was released in the UK on 10 June 1985, given a scattershot title that came to McAloon in a dream. In the US, it went out under the even worse Two Wheels Good due to a contractual falling out with the actor’s estate. Both sides of the Atlantic shared the same dowdy sleeve, underselling the modern sounds contained within it, featuring the band on a winter’s day, the sky the colour of spoiled milk, gathered around a motorcycle. An obvious nod to The Great Escape, sure, but also a downcast inverse of another record that featured a hero on a motorbike: Purple Rain. That summer, McAloon would tell NME that Prince’s Little Red Corvette was “the song I most wish I’d written” (in turn, NME clutched their pearls that the Minneapolis superstar was “the polar opposite to everything that I perceive and find wondrous in the world of Prefab Sprout.”)

For half of the Steve McQueen band, however, summer 1985 would become memorable for something completely different. Guitarist Kevin Armstrong was already working with David Bowie recording Absolute Beginners when the Live Aid call came through. Armstrong recruited McQueen alumni Thomas Dolby and Neil Conti to be Bowie’s hastily assembled stadium band, just for one day. In his memoir, Dolby remembers watching Queen’s 6.40PM performance from a descending helicopter, next to a chain-smoking Thin White Duke.

For Paddy McAloon and Thomas Dolby, Steve McQueen was the start of a five year collaboration. 1988’s single ‘The King Of Rock’n’Roll’, a vivid and detailed Dolby production, became the band’s sole top 10 hit. The other material on From Langley Park To Memphis without Dolby doesn’t quite land. 1990’s remarkable Jordan: The Comeback bested Steve McQueen in both scale and eccentricity, a conceptual epic which painted American pop icons in Biblical frescos. But that would be it. Both men have made fine work outside of their collaboration, but alone neither would come close to touching the peaks that their unlikely union had allowed to flourish. They needed one another, and brought things that neither could find alone.

Then and now, adventurous listeners who would otherwise hold little regard for 1980s indie have recognised brilliance in Steve McQueen. In a 1988 NPR appearance, Arthur Russell singled out Prefab Sprout, and the recording techniques used by Dolby, for praise (“more and more you find that really breathy EQ on the vocal. That’s something they seem to be very much on top of.”)

In a 2020 appearance on Unsung podcast, Caroline Polachek spoke expansively about the influence that Prefab Sprout had on her career. “The beat is grounded in this absolutely pristine R&B groove, polished to the high heavens, but with these lyrics that are so abstract,” said the progressive pop pioneer of the Dolby produced single ‘Wild Horses’, “it’s so sensual and so gorgeously produced and I knew I needed to find out more about this band.”

Today, Steve McQueen is dealt short shrift by the retrospectively applied sophisti-pop sticker, that label a red herring for something far more interesting that flashed across the middle part of the 1980s. For a short year or two during the high Thatcher period, a new progressive UK sound emerged out of sudden technological breakthroughs (and splintered just as fast.)

Something bright, edenic and heady audible across ostensibly very different releases like The Blue Nile’s A Walk Across The Rooftops (1984), Kate Bush’s The Hounds of Love (1985), Pet Shop Boys’ Please (1986), Coil’s Horse Rotorvator (1986) and Talk Talk’s The Colour of Spring (1986).

New machines, and strange human voices. In a 2020s moment that increasingly wants music to be explained away into strict digital genre boxes, these are albums that are beyond category or comprehension. Sometimes even to the very personalities who came together to make them.

With thanks to tQ writer Eden Tizard for the Arthur Russell link and conversations that helped inform this piece, and to the excellent Sproutology web archive