Viewed from the outside, by 1996 Stereolab must have seemed like a unit that could only ascend. Half a decade into the project, affectionately termed “the groop” by its nucleus members, the couple of Tim Gane and Laetitia Sadier, Stereolab appeared to be going overground. 1994’s Mars Audiac Quintet had been their poppiest, sharpest work thus far – and they had been rewarded with a near hit single in ‘Ping Pong’ and their first top 20 charting album. They’d toured the US as part of an all-star Lollapalooza line-up, becoming unlikely bedfellows to the Beastie Boys, Smashing Pumpkins and Green Day. And to the record buying public, the 1995 release of the second in their continuing Switched On series – gathering up odds and sods of non-album material – would suggest a band at the peak of their powers. Internally, however, things were very different.

“It was a difficult time” reflected Tim Gane to the Guardian in 2019, “there was a lot of bad feeling, a lot of relentless touring.” Mars Audiac Quintet had felt like as far as the group could take their formula of motorik rock and lounge-y avant-pop. For about a year, almost everything they tried seemed to be another creative dead end. Recording sessions had been a disaster. “It was bass and saxophone and drums playing nearly the same riff for eight minutes” remembered Gane, “the engineer was like, you’re going to sell three copies.”

The band had hit an impasse, and something had to give. Always one to keep busy, Gane had been invited to cover a track by 1960s psych pioneers the Godz, alongside bands like Comet Gain and the Apollos for tribute compilation Godz Is Not A Put-On. Listening to the track, ‘ABC’, it might sound fairly unremarkable – probably one of the least interesting recordings Stereolab put their name to around that time – but this throwaway cover would unlock the door to the brightest purple patch in their recording career. This is the stuff we talk about when we talk about Stereolab.

Like Remain In Light or Kid A, a change of approach opened up completely fresh pathways. It’s very easy to see how Stereolab could have become something that peaked with ‘French Disko’ or ‘Jenny Ondioline’ – instead, Emperor Tomato Ketchup would be one of the few 1990s rock albums that could look its contemporaries in hip hop or electronica in the eye. More than this, it was the supposedly retro, supposedly backward looking Stereolab who were doing it. It created a formula that they would then apply to glitchy electronica with 1997’s Dots And Loops, and their outlier avant-garde masterpiece, 1999’s Cobra And Phases Group Play Voltage In The Milky Night.

Gane took a four-note phrase from the original track and began to loop it, and then added a drum track and looped that too. Hardly revolutionary for the mid 1990s, but for Gane it had become a lightbulb moment. What if he applied the same logic to his own band? “It was at the point when the rhythm went down that I had an insight into how to crack open something new in the music” explained Gane in the liner notes to the 2019 reissue of Emperor Tomato Ketchup. The motorik rhythm on which Stereolab had been founded had driven them into a corner, but suddenly – thanks to looping small cells of music and building interlocking rhythms and ideas – the possibilities were endless.

"It was like you’d come from a cave, or across a mountain, and there was another totally different landscape, like on the original Star Trek where every day you could look forward to going to a new star system” explained Gane to the Guardian. It began a period “where everything you try kind of works. There’s no bad door – whatever one you go through, it’s another kind of greatness. It was a very ‘up’ period for me”.

John McEntire had first met Stereolab when his then band, Gastr Del Sol, had opened for them in his native Chicago. He quickly recognised the group as kindred spirits – speaking to the New York Times in 2019, he remembers being struck by Gane’s “totally encyclopedic knowledge of everything, and this is not an exaggeration at all”. McEntire would shortly form Tortoise, releasing the excellent ‘Gamera’ single on Stereolab’s own Duophonic label the same year as Mars Audiac Quintet – but really, McEntire wanted to record with The Groop. At the end of July 1995, with a whole album of new material demo’d, mostly using Gane’s new writing method, Stereolab flew out to Chicago. Most of the album would be recorded at McEntire’s Idful Studios. “We were excited to be in a new environment and working with the new friends we had made” wrote Gane in the Emperor Tomato Ketchup liner notes, "the whole thing about working with John at Idful was to be about exploring any and every kind of sonic possibility we wanted to”. After sessions, the band and McEntire would hang out at the Rainbo Club directly below the studio – commemorated in the Dots And Loops track ‘Rainbo Conversation’.

Many critics would pin Emperor Tomato Ketchup’s startling opening track, Metronomic Underground, on their new producer – Gane was keen to stress that the track had been written fully prior to flying Stateside. ‘Metronomic Underground’ is the first serious vindication of Gane’s new writing method. Until this point, Stereolab had always sounded like a guitar band – though Laetita Sadier may have regarded shoegazers as Thatcherites, in the early 90s Stereolab made sense as part of a recognisable group of guitar acts. This would no longer be the case, Gane’s new writing method rendering them more singular, especially in the plodding Britpop mid-90s.

Let’s start with how ‘Metronomic Underground’ sounds. For starters, it’s a lot like Gil Scott-Heron’s ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’. It’s also a lot like Yoko Ono’s ‘Mind Train’. Listen to Nancy Sinatra’s ‘Drummer Man’, especially the drop around the two minute mark, and you can hear that same groove. In 1994, if you bought Warp’s celebrated Artificial Intelligence II compilation then you’d be confronted with the slightly hip hop, slightly Krautrock throb of ‘Arcadian’ by Link – and it sounds a little like that too. Where Stereolab records had previously tended to be crammed full of mid-range frequencies, the track begins unusually sparse – the bassline holds with Samurai stillness as a conveyor belt of sonics pan left to right, creating and dissipating tension like a good dance record. It sounds like a band performing their own remix (a great idea for any indie band, really), its dubby sonic games with space and phasing earning it the working title Chrome Tubby.

The first vocal you hear on the album isn’t Laetita Sadier but Mary Hansen, introducing a two-part harmony between Sadier and Hansen that had arrived at a real sophistication by this point, inspired heavily by Brazilian music and sounding quite unlike anything else in Western pop. Emperor Tomato Ketchup would be the first album written and demo’d specifically with their vocal interplay in mind. Sadier’s lyrics, incanted with glacial coolness, are unusually Dadaist, throwing the track even further off-kilter. “Crazy, sturdy, I torpedo” is repeated before a meditation on the vacuous and the infinite. During the band’s painful creative impasse, Sadier had been turning to the I Ching – “it can tell you scary things” she told the Guardian in 2019, "It’s a harsh book" – which fed into ‘Metronomic Underground’s lyrics. Discussing Stereolab’s great leap forward to Melody Maker in 1997, Sadier would jokingly compare their work with another key band of the era. “Look at Oasis, they have one song. No, they have two songs. But we have three.” She isn’t really wrong – ‘Metronomic Underground’ would introduce lengthier, funk based pieces to the Stereolab oeuvre, which would become a key lynchpin of their work from that point onwards.

When the artist Charles Long was creating his abstract, poppy, slightly phallic sculptures, he liked little more than to listen to Stereolab at full volume. With an exhibition coming up at New York’s Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, he invited Stereolab to collaborate – they would create a piece of music for each installation in the exhibition. The brief presented a useful creative challenge to the group, forcing them towards a stillness that had previously been absent in their work – the resulting EP, Music For The Amorphous Body Study Centre, is some of the best work they ever produced.

Sean O’Hagan’s strung arrangements would be matched by burgling electronics, equal parts playful and optimistic. ‘Cybele’s Reverie’ continues what they started on that EP to devastating effect – one of the most singular and straightforwardly pretty moments in the Stereolab back catalogue. Closely inspired by French ye-ye pop, it is – by the Groop’s standards – a very simple, structurally classic piece of writing. Sadier’s lyrics, roughly translated, focus on childhood, asking what to do when we’ve done, read, drunk and eaten everything in human experience, and contrasting that with the purity of the childhood experience. "Childhood is much nicer” she sings in the verses, "childhood brings the magical.” It would be the album’s lead single, underlining the extent to which Gane and Sadier had – to use the rock journalism cliché – transcended their influences.

“One set of people can’t believe we’ve made such a pop record” said Sadier to Melody Maker at the time, “and another set of people can’t believe we’ve made such an experimental record.” This duality gets to the heart of Stereolab’s appeal, and nowhere is that duality better expressed than on ‘Percolator’ – the pop and the experimental, the head music and the body music, in perfect symbiosis. Another early fruit of Gane’s new writing technique, its 5/4 time signature gives it a nervous feeling, emphasised by its noodling, proggy bassline and stabs of dissonant jazz chords – not to mention Ray Dickarty’s excellent saxophone part. You can draw a line from that Godz cover to ‘Percolator’, it does many of the same tricks, yet somehow creates brilliant pop from the discord.

Though Emperor Tomato Ketchup would mark the end of Stereolab’s affair with motorik rhythms – they would almost never be used afterwards – tracks like ‘Les Yper Sound’ and ‘Emperor Tomato Ketchup’ are the band’s best, most interesting expressions of that beat. Where earlier records had seen a piledriving motorik beat slathered in distorted guitars, here the sonic surfaces are crystal, wipe-clean. Gane was bored of the rhythm guitar he’d applied to that beat across previous albums, and asked McEntire to filter his guitar through synthesisers, rendering it crisply unrecognisable.

Stereolab’s interest in electronic music, always there, was dominating the group by this point – indeed, it’s this interest that affords Emperor Tomato Ketchup its modernity, such was the speed and flamboyance with which developments in those genres had overtaken rock by the mid-90s. ‘OLV26’, which sounds like Suicide, genuflects to popular electronic music’s year zero by looping a phrase from Kraftwerk’s ‘Autobahn’ (this would then be used as part of Stereolab’s ear-splitting 1997 Nurse With Wound collaboration Simple Headphone Mind).

One of the most interesting sub-plots across subsequent Stereolab albums would be their interest in 20th century American minimalism – this begins in earnest with the syncopated guitar part that drives ‘The Noise Of Carpets’, coming quite obviously from Steve Reich. Gane remembers recording the track, sat eyeball to eyeball with John McEntire to maintain timing. The only straight-up guitar track on the record is ‘The Noise Of Carpets’, a terrific and brief blast of power pop that sounds more like Buzzcocks than anything, complemented with Sadier and Hansen’s dual vocal attack, relishing in a takedown of 90s “fashionable cynicism.”

Stereolab’s politics made them outliers in the post-ideological, end of history 1990s. Political indie in the preceding decade had failed to achieve anything interesting even on its own terms – held back by its formal traditionalism, nostalgia and Old Left earnestness. Few had tired of political indie more than Tim Gane, one of its active participants as the guitarist in McCarthy. From its politics to how they approached the music industry, much of Stereolab was a reaction against Gane’s experiences in that band.

“For most people politics in music means Billy Bragg” said Gane to NME in 1996, “and that’s why I hate most political bands. The association is always with bands who haven’t had the imagination to combine the music with the lyrics.”

Sadier’s lyrics would prove a thrilling counterpoint to this. Both literally and metaphorically a child of May 1968, Sadier went for the philosophical over the domestically political, and cited texts like Guy Debord’s The Society Of The Spectacle as an influence. She understood that form and function had to collide, and began to hone a talent as an effective, memorable and witty political lyricist. Fresh from the success of having nearly brokered an explanation of the Kondratiev Wave into the top 40, Sadier’s political writing is at its most focused on Emperor Tomato Ketchup. She observes how institutions designed to serve society end up reversing that relationship (‘Tomorrow Is Already Here’), how capitalism divides and conquers (‘Les Yper Sound’) and probing the bluff and confidence trick of late capitalist society (‘Motoroller Scalatron’). Simple messaging, repeated phrasing, plenty of question marks – Sadier’s work has all the hallmarks of effective political communication. Juxtaposition was sonically always one of Stereolab’s great powers, and what Sadier achieves here is a forcing of political content into pretty melodies that were previously unused to such company. Alongside certain psychedelic soul records, it’s only really Stereolab that allows me to luxuriate in imagining a better society, how it might feel, look, what we might do. And if it doesn’t do this for you, it’s certainly more perceptive than the other path politics and pop music was on by 1996 – Noel Gallagher’s eyebrow raising declaration at that year’s Brit Award stage that only seven people were giving hope to young people in the UK, and those people were the 1996 lineup of Oasis, Alan McGee and Tony Blair. La resistance!

Of course, we now know that life inside the Lab was a little less harmonious than it may have appeared at the time. “Tim took most of the artistic decisions in terms of writing, composition, arrangements” explained Sadier in a 2015 interview with Red Bull Music Academy, "and I had no say. I did want to write songs.” Furthering this in a 2019 interview with the Guardian, Sadier explained, “that was the contract that I did not know I was signing with Tim, that he would control the music absolutely and entirely.” Sadier clearly had plenty to offer, and it’s worth reflecting on what could have been had her input been better expressed in the Groop. “I would hear the songs on a four-track demo, and their power and their essence, and I felt, this is beautiful. There was a way of working that was very industrial and mass produced, and that was really driving me crazy.” Gane maintained control over Stereolab musically until their split in 2009.

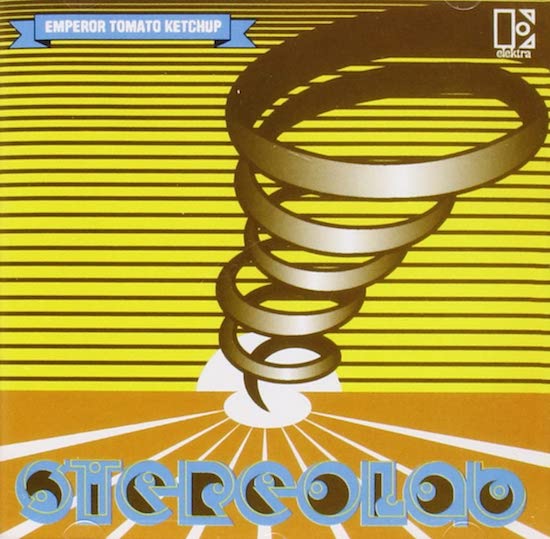

Once the album was completed, Stereolab brokered a deal with Elektra Records who would release the record globally, whilst domestically it would still be released by the band’s own Duophonic imprint (owned three ways, to this day, between Gane, Sadier and manager Martin Pike). Elektra afforded the group total creative freedom. Its album title would be lifted from an experimental Japanese film by Shūji Terayama, whilst its artwork would be heavily inspired by the sleeve design of an LP of the music of Hungarian composer Béla Bartók.

Though Stereolab had a complicated relationship with the music press – not least in Sadier’s native France – reviews for Emperor Tomato Ketchup were glowing. “This is what all those years toiling away in the lab were for” wrote Ted Kessler, reviewing the album for NME, “all their equations finally make sense.” Simon Reynolds, one of the band’s most consistent champions, declared the album the work of an “inspirational one-off… trying to pull off this same miracle would be pointless and redundant”. Reynolds was right, but Stereolab were beginning to emerge as a powerful influence. Britpop had rendered Stereolab’s work that bit more singular, more separate, and around this time a disparate group of crate-diggers and musicians began oscillating around the Groop. You can hear the immediate influence in Plone, Stereo Total, Labradford, Quickspace Supersport, though the very best of these would be Broadcast, whose Book Lovers EP would be released by Duophonic the same year as Emperor Tomato Ketchup. Something was in the air intellectually too – in 1997, you could watch Jonathan Meades on BBC Two asking many of the same questions that Stereolab’s music posed, like what happened to our vision of the future? By the mid 00s, these ideas were everywhere – the films of Adam Curtis, the blogs of Mark Fisher, histories by writers like Andy Beckett and Owen Hatherley. Stereolab caught an idea that endures to this day.

“We’re working at setting a precedent” explained Sadier to John Mulvey in NME as Emperor Tomato Ketchup was released, “that’s how you move along. You need some bands to just make a joint. My Bloody Valentine were a joint, and prior to that the Velvet Underground. Maybe we’re one of those joint bands that make things go a notch in a different way.” Stereolab were unlucky in their timing, but this happened all the same. Almost as soon as they split in 2009, their stock began to rise and rise. The bigger slumps and bigger wars and smaller recoveries that Sadier had hypothesised had come to pass. Similarly, an early 2010s psychedelic revival in the UK proved to be a busted flush, but did create a ready audience who quickly gravitated to Stereolab. In the last two years alone, you can hear the ricochet of Stereolab in thrilling records by Jane Weaver, the Orielles, Vanishing Twin, Kit Sebastian, Whyte Horses, even in UK jazz like Tara Clerkin Trio. Thank God, then, for that Godz compilation.