Everyone – except, I suppose the most hardline of neophiles – has albums they return to again and again. I long thought of mine as comfort records, and I suppose some of them are. But others, I’ve realised over time, are something quite different. They’re the albums I keep revisiting because every listen brings something new. However many times I play them, I never hear the same album twice. Remain In Light by Talking Heads, for example, which I have played more often, more consistently and throughout more years than any other recording; so I adjudge it to be my favourite album ever. Or Gene Clark’s No Other, which repays each hearing by illuminating some or other long darkened recess of the soul. And Spiritualized’s Lazer Guided Melodies, which a quarter-century of close acquaintance has only rendered richer and more radiant.

Lazer Guided Melodies is exquisite. I think I now have a better understanding of how it was made to be so than when I first heard it; what it drew upon, where it found its antecedents. It was as if I began at an ending, the point where various threads fused, then traced them backwards to earlier work. But then that’s often how one discovers music – first the influenced, then the influences. The Velvet Underground and Pink Floyd, I already knew well enough; Krautrock, Suicide, hard bop, modal jazz, David Axelrod, Steve Reich, Terry Riley – these lay ahead for me. Spiritualized are a one-band encyclopaedia of a certain, genre-spanning idiom of cool music (cool in more than one sense of the word.) And this makes them fascinating. But Lazer Guided Melodies required no such background knowledge for one to be fascinated and enthralled by it. I loved it from the moment I first heard it. It was, and is, an album you can venture deep inside, along a single, straight pathway that is somehow always winding, and always follows a different route. It has, as its title suggests, a linear directness. It is severe, mathematical, metronomic. Yet it is also languid, rhapsodic, as fluid and sensuous as the plastic figures on its cover. How are these contradictions possible? They aren’t. Much of the greatest music is impossible. That’s the wonder of it.

My copy of the album is the 1992 CD on which its 12 songs are sequenced as colour-coded movements (Red, Green, Blue, Black) spanning its length. While not quite as bloody-minded as Prince sequencing his Lovesexy CD as a single track, this still indicates a determination to tell you how to listen to the thing. It’s not to be taken piecemeal. Red opens with ‘You Know It’s True’, a gentle, repetitive wash of dejection and reproof that sets the tone not only for the rest of the album, but more or less for the rest of Spiritualized’s oeuvre. It’s not that Spiritualized have no range to their emotional palette. On the contrary, few bands have utilised so exhaustively every shade of black. Again, this is impossible, but to paraphrase the song’s own lyrics, what can you do? Spiritualized are distillers of sadness. Each song finds new ways to be inconsolable. There are two palliatives, and two only: love, and drugs – and soon, one realises, these two are interchangeable; the one can almost always be heard to mean the other. They are the relief and the cause of all pain. Love causes hurt; drugs ease hurt; drugs become love; love causes hurt. On and on it rolls, ever unfolding along the loops and pulses and motorik rhythms, through the formalist patterns, the classical instrumentation and chamber-pop arrangements. Lazer Guided Melodies is serene – even when the horn stings arrive on ‘If I Were With Her Now’, they ease, swell, glide into place – and it is uncommonly beautiful.

You know I’m tired, I got a fevered brow

You know I’d change if I were with her now

You gave me drugs you said would cure my ills

They may cure yours but mine are with me still

And behind it the rhythm canters, the bass lollops, the guitar jabs and recedes, jabs and recedes, and it all fades into spacey bleeps and twangs, then courses back in for ‘I Want You’ and its insistence not only on desire but on admonition:

I want you to realise it’s my life

I want you to realise it ain’t paradise

When I first heard it, ‘Run’, which opens the Green section, struck me an ingenious joke: what if you did JJ Cale’s ‘Call Me The Breeze’ in the manner of John Cale? Which is not to say it’s only a joke. It’s a brilliant tune, one of the keys to the album. And the Okie Cale’s gnomic, laid-back lyric to ‘Call Me The Breeze’ becomes a Jason Pierce lyric just like that: those simple, repeated phrases, not exactly mysterious, yet seldom more than vague. Pierce writes in plain statements of feeling; but what the feelings mean is always open to interpretation. The phrases are familiar from the rock & roll canon, but whereas Pierce’s compadre Bobby Gillespie (of whom more anon) will use such rote expressions as a direct line into that heritage, to the point of comedy, with Pierce it’s always more opaque – not least because Spiritualized seldom sound in the least bit traditionally rockist. Take ‘Step Into The Breeze’, whose title nods to the original of ‘Run’: "So fine / Got everything I need / You got me down on my bended knees." It might be the lyric to a Black Crowes number, but instead it’s part of a dreamy, droning, (probably) smacked-out paean to – well, what? Sex? Drugs? Rock & roll? In the landscape of Lazer Guided Melodies, it’s all the same, all one hazy blur.

Spiritualized were often lumped in with the shoegaze movement around that time, but the similarity was entirely on the surface, because shoegaze took place almost entirely on the surface. Spiritualized had deep currents running underneath, just as My Bloody Valentine and the Cocteau Twins did. The emotions, the themes, may be a hazy blur, but the arrangements, the instrumentation, are precise and meticulous and astonishingly artful. They didn’t smother their songs with effects pedals like ketchup on a mediocre meal. Everything had a purpose. The jazz piano that showers glittering motes of light over ‘Take Your Time’, for instance, and the three-note saxophone riff circling beneath ‘Shine A Light’, which combine for the Blue phase of the album. And the Black finale, with all its longing and heartbreak:

Girl, it’s like an angel’s sigh

When I see you walkin’ by…

Girl you know I’ve nothin’ left

I’m just a feather on your breath

(‘Angel Sigh’)

From which it seems an inevitable conclusion when ‘Sway’ lies back on the floor, stares glassily upwards and intones, "Hey mama, take your cool love away from me / Take it away and let me bleed in peace." It’s rock & roll by the numbers, familiar in every way in its vernacular, yet eerie and unknowable in its effect: in short, uncanny. Just as when keyboard player Kate Radley counts the passing measures on the stately ‘200 Bars’, and one can feel the seconds of one’s life slipping inexorably past, a ticking meter tracking the time that Pierce then sings he’s losing track of, before the album suddenly fades and dies with Radley’s whispered "Two hundred."

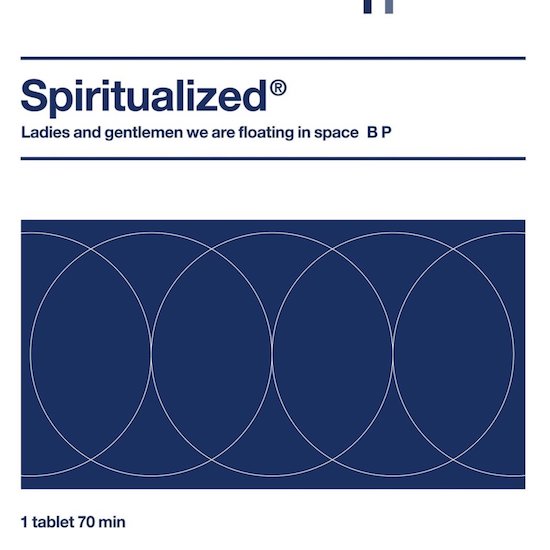

Lazer Guided Melodies is not a minimalist work in the ordinarily understood meaning of the term. It places layers upon layers, often adding to rather than stripping down its sound. Yet it is never more ornate than it needs to be, and always as stark as it possibly can be without forgoing something essential. This, as much as its careful construction, makes it as clear and pure a thing as it is. Five years later, following their undervalued second album, Pure Phase, Pierce and a new line-up, retaining only Radley from the group that made Lazer, released another quite astonishing record. The first album remains my own favourite. Yet Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space is without question a masterpiece.

One of the most extraordinary things about it is the way it manages to sound exactly like Spiritualized while following a radically different approach to the one that established them. Where Lazer is sparing – it does not pursue a less-is-more aesthetic, but it never exceeds what is exactly enough – Ladies And Gentlemen is unabashed in its maximalism. More everything, all the time. Only too much is enough.

Five years isn’t a long time in music, now. A band can go away for five years and come back scarcely changed. It used to be much longer, before the pace of change slowed, and time seemed to stretch. The five years between Lazer and Ladies and Gentlemen, set against the equivalent periods from the previous four decades, were far less convulsive. The other big, and big-sounding, indie-rock albums of 1997 were Radiohead’s OK Computer and The Verve’s Urban Hymns, each being the culmination of something its creators had been audibly striving towards for much of their existence. But Ladies And Gentlemen was no less than a shock. It wasn’t just that the aesthetic had changed or that fresh influences had transformed the sound. The spirit of the thing was something else again; and when your band is called "Spiritualized" that is no small matter.

The most striking thing about Ladies And Gentlemen is not that it draws in gospel, blues and free jazz to its ambit, although these profoundly affect it. Nor that it is so much louder, heavier and more chaotic than its predecessors, although it is. No, it’s the emotional difference. It is a study in two passions previously lacking in Spiritualized’s work: rage, and disgust.

What was Pierce so angry about? Not, it turns out, his break-up with his partner Radley, who had taken up with, of all people, Richard Ashcroft. Pierce has said many of the songs for the album were written before he knew of that – although the recording sessions, with Radley still in the band, must surely have been bracing. Mainly, Pierce seemed angry with himself. With being, in every way, wasted. Because Ladies And Gentlemen is a heroin album if ever there was one. It’s entirely upfront about it. There have been angry heroin records before: the Velvets made them, obviously, and then there’s Dirt by Alice In Chains. Yet Ladies And Gentlemen is on a different plane to those. In a weird way, it bears more relation to Primal Scream’s Screamadelica than to any of those records, or even Spiritualized’s own, previous releases. It is to smack what that album is to ecstasy: a kind of symphonic, psychonautic exploration to the far perimeter. Here be dragons; and it is an open question as to who chases whom.

The title of signature tune ‘Come Together’ tips the wink; Pierce was surely aware it would evoke Gillespie’s song. Where that celebrated the orgasmic possibilities of music (from the same sources Pierce now deployed: "gospel, and rhythm and blues, and jazz … gospel … gospel"), this one is a bitter diatribe at its author, a searing cosmic rock number berating him for his own weakness. Once again, love=smack=love. The title track, the opener, finds him falling, oh so slowly:

I can’t help falling

Falling in love with you

I will love you ’til I die

And I will love you all the time

So please put your sweet hand in mine

And float in space and drift in time

All the time until I die

We’ll float in space, just you and I

And then, the payback. ‘Come Together’ kicks in, furiously, and

Little Johnny’s sad and fucked

First he jumped and then he looked…

So little J’s a fucked up boy

Who dulled the pain but killed the joy

And little J’s a fuckin’ mess

But when he’s offered just says yes

Love is smack, smack is love. Drugs are the love he’s thinking of. ‘I Think I’m In Love’ runs the title of a song wherein each hopeful line is followed with a sardonic, despairing counterpoint – and this love is, "Love in the middle of the afternoon / Just me, my spike in my arm, and my spoon." The tracks of time, those tracks of mine. Hey, man, there’s a hole in my arm where all the money goes. Jesus Christ died for nothin’, I suppose. (A direct lift from John Prine, that.)

And those are just the overt references. There is barely a moment on the album when Pierce is crooning at the object of his devotion or howling at the source of his betrayal when the "you" he sings to, the putative lover and traitor, is not more likely to be the drug. So no wonder it’s starving hysterical naked. No wonder the scrupulous, sublime order of Lazer has been supplanted by songs that hang in the air, float off into empyrean black, then come crashing back to earth in a maelstrom of noise, distortion and dissonance. By the time the closing ‘Cop Shoot Cop’, a drawling, discordant, strung-out-blues epic, hits its 17th minute and dwindles into nothingness, you’re dazzled, breathless, spooked and, in all likelihood, would sooner actually be shot into space in a lounge suit than even contemplate a dab of smack. If this is what you have to undergo to create so traumatic and traumatised a magnum opus, better Pierce than me. No "Heroin Screws You Up" advert was ever this effective.

Maybe it has the opposite effect for some. This is, as I mentioned, cool music, drawn from a long line of cool musics. Maybe there have been kids who think that if you want to play like Pierce, you have to live like Pierce. I don’t know. It is lately my view on things that people need to go to Hell their own way. Because, when they come back, they’ll have learned all about it the only way they can.

But what if you never come back? Pierce very nearly did die, a few years later, not from an overdose, but from a bout of pneumonia; although, as he told The Guardian’s Dave Simpson, "You could argue that it was drug-related … you could argue that everything in my life is drug-related." But that’s another thing music is for. To bring back visions of other worlds we might not choose to visit ourselves. For that, you need a spaceman.