In a Holiday Inn overlooking a stark stretch of highway which cuts through the unassuming American city of Norman, Oklahoma, Horace Panter received a punishingly early phone call from his manager, Rick Rogers who was trying to find a member of The Specials that wasn’t too hungover to celebrate with him. Rogers had just got word from England that the band’s latest single ‘Too Much Too Young’ had made it to number 1, but when he woke his own roommate Jerry Dammers, he was told to calm down. And then the bandleader went back to sleep.

The Specials were just three dates into their first U.S. tour and still a few hours away from surfacing after a riotous set at Boomer Theatre the night before. Booked to support The Police who pulled out at the last minute, the band got 600 disgruntled Sting fans stomping to their frenzied ska and ratcheted rocksteady which was sweeping the nightclubs back home, though Panter mused in his tour diary that it was their rock & roll song ‘Concrete Jungle’ which got them on their feet.

The gig was a daunting prospect, and not just for fear of a hostile crowd. In his memoir Original Rude Boy, vocalist Neville Staple recalls watching state troopers clashing with a Ku Klux Klan rally on the local news. Staple and the other black members of the touring party were advised to stay in doors after the gig, echoing Norman’s not too distant civic history as a sundown town where it was once unsafe for Black people to walk the streets after dark. Meanwhile Panter and drummer John Bradbury had their post-gig celebrations cut short when the club they ended up at turned out to be a seedy strip joint. Panter registered his dismay in his diary, describing the sight of “unpleasant women taking their clothes off”. “No thanks,” he continued, “back to the Holiday Inn and bed.”

So, on the morning of 29 January 1980, this motley crew of shell-shocked and hungover Brits enjoyed a champagne breakfast in an unfriendly town thousands of miles from home where they were now certified top of the pops.

It had barely been six months since The Specials’ debut ‘Gangsters’ lit up the airwaves, reaching number 6 in September 1979. The following single ‘A Message To You, Rudy’ and their self-titled album both hit the top ten soon after, while their fellow 2 Tone luminaries Madness, The Beat and The Selecter were all riding up the charts behind them before ‘Too Much Too Young’ took the top spot. For those witnessing the exponential rise of ska’s new wave from their armchairs, it must’ve seemed like overnight success, but as is often the case, ‘Too Much Too Young’ went through a number of incarnations before the version we know and love received its first silver disc; and the roots of the song go deep.

Let me take you back to the late 1960s when The Beatles ran a poster campaign inviting hopeful songwriters to submit tapes to their newly launched Apple Records. A teenage Dammers saw the photograph of a one man band who, the poster claimed, “now drives a Bentley” and sent in a demo, but heard nothing back. No one did. The Apple office was overwhelmed with more tapes than they could listen to, and the Bentley owner was in fact The Beatles’ notorious Mr Fixit, Alistair Taylor. Undeterred, Dammers ploughed ahead, joining a succession of young bands as he consumed soul, R&B and blue beat records, like all good mini-mods should.

While Dammers was busy practicing his chops on the organ, a Jamaican music veteran was finding a fresh audience amongst British skinheads who liked their reggae kinda kinky. Lloyd Tyrell’s career began in Kingston, JA where he cut a few ska sides in the early 60s with his vocal group The Charmers for Prince Buster, and Coxsone’s Studio 1. By the end of the decade he’d gone solo as Lloyd Charmers, and hit the UK reggae chart when the Pama label issued two of his risqué rocksteady singles, ‘Bang Bang Lulu’ in 1968, and ‘Birth Control’ in 1970. The latter introduced by a jocular Tyrell asking his wife “Doris? Where di pill?” before launching into a familiar staccato organ melody.

Beyond the vocal booth, Tyrell was an accomplished piano player and organist, briefly recording instrumentals as Augustus Pablo before passing the name onto the soon-to-be king of dub melodica, Horace Swaby. Tyrell also worked closely with Byron Lee & The Dragonaires who backed him on a set of instrumentals for Trojan around the same time Lee recorded his own version of ‘Birth Control’ which, it’s probably safe to assume, featured Tyrell on organ duties.

One person paying attention was Jerry Dammers and by 1977 he had ditched the local soul circuit to form The Automatics, a multicultural rock meets reggae project, inspired by the Black and white mix-up of the Rock Against Racism movement. They soon caught the attention of impresario Pete Waterman who ran a record shop in Coventry following a short stint in Jamaica where he helped Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry’s protégé Susan Cadogan reach the UK singles chart with ‘Hurt So Good’. Waterman’s tenure as manager was notoriously brief, and ended when he attempted to show Terry Hall how to dance, but he was around long enough to get them a recording session in London where they laid down four loose demos including a tongue-in-cheek swipe at a girl who’d picked domestic life over being with Dammers. Set to a sparse reggae one-drop, and featuring a Booker T-esque instrumental section, what’s notable here is that this first recording of ‘Too Much Too Young’ bears no resemblance to Tryell’s ‘Birth Control’.

As The Automatics progressed as a live unit, it became clear that the oppositional sounds of rock and reggae weren’t gelling. While searching for the missing element which might bridge this sonic gap, Dammers heard ‘Smoking My Ganja’ by UK reggae outfit Capital Letters which offset Junior Brown’s rootical bass line with the frenetic double time guitar skanks of ska. This was it. 70s roots rhythms were ditched in favour of the blue beat sound of 60s Jamaica, with nods to R&B, soul, and rocksteady. Those burgeoning ideas on the first demo suddenly came to life when Dammers filled the empty spaces between Hall’s deadpan verses with Staple and guitarist Lynval Golding chanting Tyrell’s “gimme nuh more pickney” chorus from ‘Birth Control’.

Following an enforced name change, and emboldened by post punk’s DIY ethos, The Special A.K.A. entered Coventry’s Horizon Studios in January 79 with a plan to self-release their first single. ‘Gangsters’ captured lightning in a bottle, but they were disappointed with their attempts to record the new arrangement of ‘Too Much Too Young’ for the b-side, and ditched it in favour of an instrumental by their new drummer John Bradbury. The song remained a staple in their live sets, however, and the band recorded it once again when they appeared on John Peel’s show in May. This third recording still sounds comparatively downbeat next to the agit-skank of ‘Gangsters’ but it’s an insight into the band’s quick evolution from the raw Waterman-funded session, even if the slick BBC production doesn’t quite capture their live energy. For that, we’re lucky to have the infamous bootleg LP recorded that same month at The Moonlight Club in North London.

The deal was for The Specials to record one track during their set, a version of ‘Long Shot Kick The Bucket’, for a live compilation, so the Moonlight Club ran cables through to Decca Studios next door and captured the whole set in high fidelity. Much like the Peel session, the Moonlight version of ‘Too Much Too Young’ remains fairly laid back, but the on-stage energy is palpable, and there’s extra percussion, presumably played by Staple, which is absent on later recordings. The compilation never happened, but as the group’s star rose, an unidentified opportunist shrewdly pressed the set on vinyl which, legend has it, sold almost as well as their debut LP.

For the album sessions, producer Elvis Costello adopted a fairly austere approach, capturing the band as close to their live sound as he could achieve without leaving the studio. At times it’s sonically close to the Moonlight bootleg, but it’s on ‘Too Much Too Young’ where the band start to play around with a hint of studio trickery. After the first two minutes, and a false ending where they’d normally launch into the next song on stage, there’s a hint of echo on Hall’s voice before we’re treated to another four minutes of spacious instrumental interplay. It’s almost a dub version, and rhythmically different, with Bradbury adopting a steppers style with rimshots scattering around his four-to-the-floor kick drum, rendering it slower yet somehow more kinetic.

Somewhere between the joyfully indolent album version and the single release, the tempo shifted again. A relentless list of live dates with increasingly rowdy crowds, and no doubt the growing tensions and frayed nerves within the band, had led to much faster, harder versions of their set list. The crowds were going wild from the get-go, and instead of a third single from the album, Dammers proposed a live EP to capture the moment.

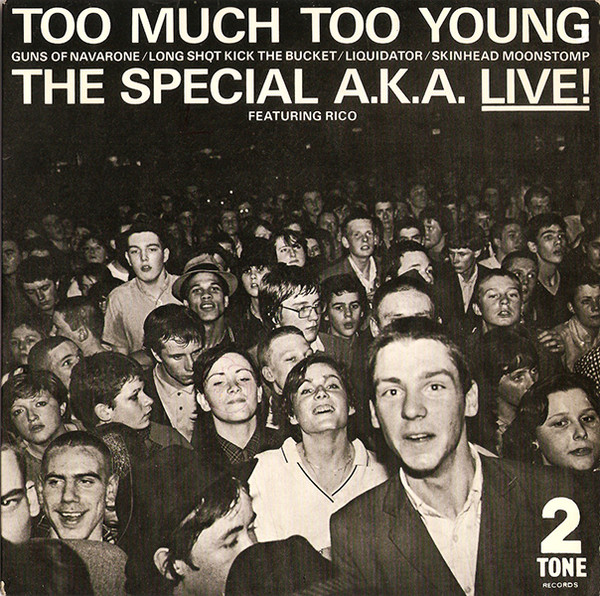

Recorded at The Lyceum in London on 25 November 1979, this super-charged steppers version of ‘Too Much Too Young’ with its accompanying live video and cover art depicting a heaving crowd of rude boys and girls, gave a terse two minute glimpse into the heavy-skanking world of 2 Tone. Add to that a medley of skinhead classics featuring Rico Rodriguez on trombone recorded on their home turf of Tiffany’s in Coventry, and it’s a perfect time capsule of the band at the top of their game, but the single’s package was in fact something of a chimera. The Lyceum gig hadn’t been filmed, so they repurposed footage shot by the BBC at a different show, then recreated the gig for pick-up shots on a soundstage in Elstree, miming along to the Lyceum audio. Meanwhile the crowd on the sleeve were actually snapped by Dammers at a Selecter gig, with a smiling skinhead pasted in the bottom left corner to cover up the one guy in the crowd with his head down. It was fine though, 2 Tone audiences were faithful to the wider cause, and the November tour featured both The Selecter and Madness on the lineup.

But on the road for five weeks in the states, The Specials were fending for themselves, often exhausted from playing two sets in a night, and anxious from the Russian roulette of potentially hostile audiences. They were now tearing through the set-list. By the final show in March at Speaks in Long Island, they’d shaved another ten seconds off the already “fucking fast” version of ‘Too Much Too Young’ which Panter now likened to hard-rockers Motörhead.

On 3 March, having ripped the Speaks stage to proverbial shreds, The Specials and entourage caught the plane back to England, with the exception of Dammers, Panter and their manager who were invited over to Debbie Harry and Chris Stein’s apartment. While eating a tuna sandwich that Harry had made him, Panter was schooled on the emerging hip hop scene which had made its way onto vinyl at the tail end of the Seventies. A jazz funk fan at heart, the bassist was quite taken with a stack of disco-rap 12”s a friend of Stein’s had brought to the apartment, and asked where he could pick some up. The following day Panter made his way up to 125th St in Harlem, and headed to The Record Shack run by South African emigré Sikhulu Shangé – a devoted supporter of Nelson Mandela – who sold the Brit copies of ‘Superappin’ by Grandmaster Flash & The Furious 5, and ‘Rappin’ And Rockin’ The House’ by Funky Four Plus One More. A few weeks prior in San Francisco, Panter had admitted during an interview for Idol Worship zine that in his downtime he listened to “anything but reggae, blues and ska.” These slinky disco-rap tracks would inspire a future project, but not before returning to Coventry where he slept for 18 hours straight.

Likewise, Dammers had been affected by the easy-listening instrumentals playing through tinny speakers in elevators and hotel lobbies on tour. Back in England he bagged a Yamaha Electone organ and began toying with its synth sounds and blippy drum machine presets which approximated samba and bossanova beats. Perhaps it was cathartic to write musak-inspired melodies at home while the band continued their chaotic live shows to thousands of pogoing lunatics. Footage from gigs in Japan and at the 1980 Montreux Jazz Festival show ‘Too Much Too Young’ still clocking in at less than two minutes. In Ska’d For Life, Panter described the trip to Montreux as “chilly” adding that “the locals look like everyone drives a Bentley.” It remains unconfirmed whether Alistair Taylor lived there at the time.

A return trip to NYC to appear on Saturday Night Live offered up anxiously fast renditions of ‘Too Much Too Young’ and ‘Gangsters’. This was Two Tone at its most ferocious, and many cite this performance as the zero point for the ska-punk movement which would dominate in the U.S. well into the 90s.

But had the tempo gotten out of hand at the start of the eighties? The next wave of 2 Tone-inspired bands often lacked the nuance of songs like ‘Blank Expression’ and ‘Doesn’t Make It Alright’ – which also interpolated the descending bass motif from ‘Birth Control’ – opting for a good old fashioned knees-up to keep the crowds dancing. Dammers, however, took The Specials in a downtempo direction with just a handful of dancier moments making the cut on the second LP. Side B of More Specials was especially introspective, seeing individual members of the group coming to the studio to overdub their parts in isolation, a process which divided an already fractious band.

More Specials was a critical success and reached the top 5 in October 1980, but the group was on the brink of collapse. Bradbury and Staple both started their own labels, while Hall was writing songs for a possible new project, which would eventually come to fruition and include Staple and Golding as members. Panter was distancing himself too. Tired of all the in-fighting and desperate to enjoy making music again, he booked some studio time on the sly and recorded his own approximation of a hip hop record; the remarkably ridiculous ‘Barnsley Rap’ featuring rhymes about flat caps, whippets, and tripe & chips. It’s merely an oddity in the early story of UK rap, but its origin via Blondie, and Panter’s trip to Harlem renders it notable, and not least for the deftly produced disco backing track.

Returning to the same studio where Panter recorded ‘Barnsley Rap’, The Specials would lay down their last three songs together before they returned to number 1 with their swan song ‘Ghost Town’ in July 1981. Just over 18 months since they’d first topped the charts with ‘Too Much Too Young’ which was conspicuously absent from a few shows on their final tour in the U.S. that summer. They officially split in the autumn.

Lloyd Tyrell would stick around in the UK, working on lovers rock, soul and even jazz with UK reggae legends Dennis Bovell and Mark Lusardi well into the 21st Century. He died in 2012.

During the mid-80s the owner of the strip bar in Norman, Oklahoma was arrested repeatedly and charged with possession of drugs, and one time for hosting a dancer who exposed “the areola of her breasts”, for which he was fined $300. Then, in 2017, the town’s DeBarr Avenue, named after a local grand dragon of the Ku Klux Klan, was renamed Deans Row after years of campaigning.

Pete Waterman remained a fan of The Specials, despite being sacked, and 2 Tone would inspire his own PWL label which would score ten UK number 1’s including Kylie’s ‘I Should Be So Lucky’, Rick Astley’s ‘Never Gonna Give You Up’ and ‘Respectable’ by Mel & Kim, the latter of which features a walking bassline in its refrain almost definitely lifted from ‘Gangsters’ by The Specials.

Horace Panter turned his back on hip hop after a 2nd Barnsley Bill single. He’s an accomplished artist now with work that occasionally nods to the pop landscapes of Ed Ruscha. Jerry Dammers currently holds the record for appearing on not one but two UK number 1’s recorded live at Tiffany’s in Coventry, having been in the crowd singing along as Chuck Berry recorded ‘My Ding-A-Ling’ at the venue in 1972 when it was still known as The Locarno.