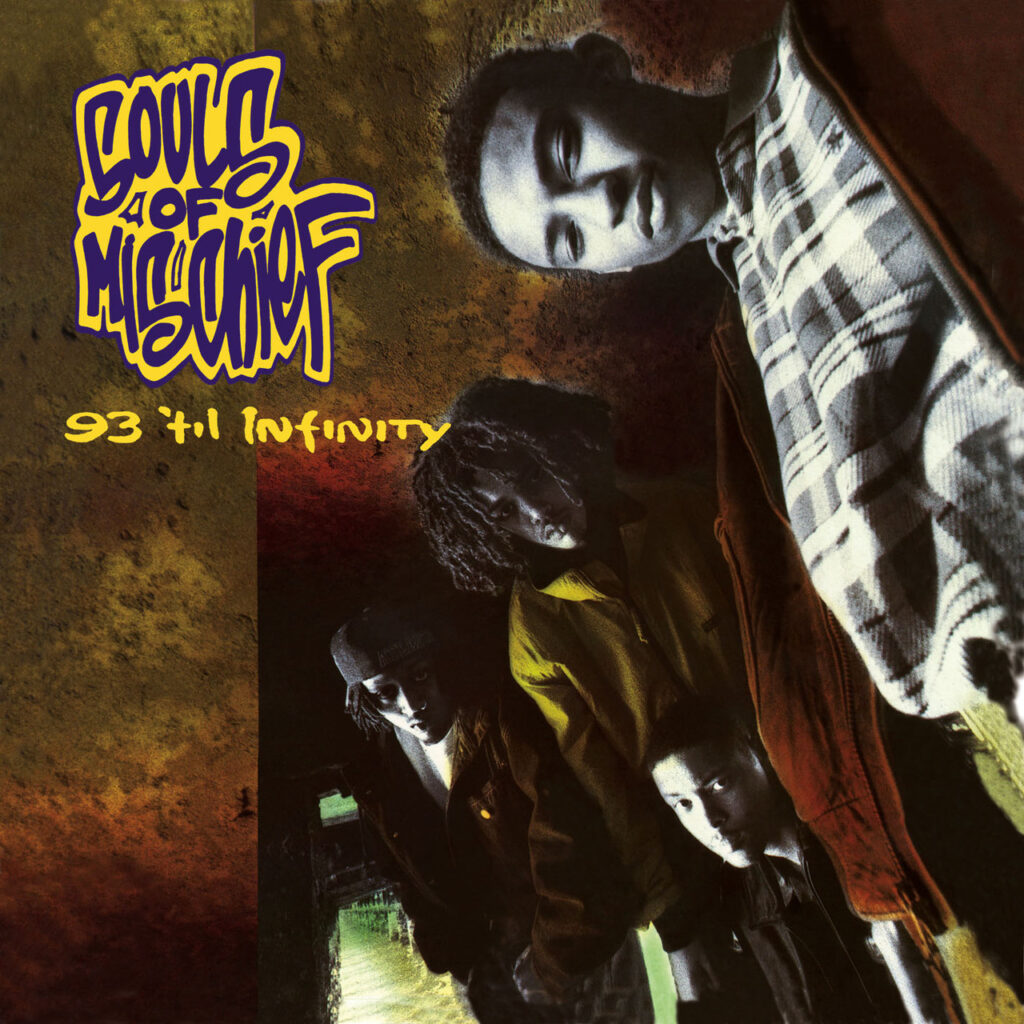

On the face of it, it’s one of hip-hop history’s most perplexing mysteries – if, admittedly, perhaps not the most pressing. How come the Souls of Mischief’s truly excellent debut didn’t turn the band into a household name – at least, in the sorts of households where the likes of De La Soul or A Tribe Called Quest needed no introduction? Why didn’t a group as uncommonly talented, who arrived with a commendable pedigree and signed to a powerhouse label, at a point in the genre’s history where the music was no longer the preserve of purists or experts, and with a record that contained little that would put off or alienate the casual (no pun intended) listener, not just succeed in establishing themselves and creating a fan base that would sustain a decades-long career (which it did), but go on and properly crack the mainstream?

There is little here for anyone to dislike, never mind be afraid of. 93 ‘Til Infinity is a gem – focused, sharp, lyrically bedazzling, musically rich, complicated yet easy-on-the-ear, clever but never indulgently show-offy. The emcees’ effortless, effervescent flows ring with a joie de vivre all but absent in today’s lackadaisical, formulaic mainstream hip hop, and which was pretty remarkable back at the close of the Golden Age too. The production is handled with a similarly light touch, the deep knowledge of some lesser-used colours of the sample-wielder’s palette carried lightly, nothing deployed in a way that suggests we are supposed to be impressed by the scholarship rather than wowed by the tunes. Yet it remains very much a specialist’s choice – an album loved by those it touched, yet which today stands all but unknown among a wider world that would, surely, have taken it to their hearts with every bit as much gusto as they’d embraced 3 Feet High & Rising or People’s Instinctive Paths… a couple of years before. To take a leaf out of the Blastmaster’s book: why is that?

The set-up looked to have gone pretty well. Souls – four lads then just 18 years old: Tajai, Opio, Phesto and A-Plus – were already a name on the more obsessive rap fan’s radar, on account of their membership of Oakland’s take on a rap dynasty, the Hieroglyphics. This was some years before coming out after your mates had already established themselves was a prerequisite to getting a major record deal, but there were already some precedents – the Juice Crew and EPMD’s Hit Squad key among them. Hiero’s lead-out man was Del Tha Funkee Homosapien, a relative of Ice Cube whose debut, I Wish My Brother George Was Here, had done some decent business after being released by Elektra in 1991, and with its infectious single, ‘Mistadobalina’, getting approving nods from the kinds of people who didn’t listen to a lot of rap but kinda dug that De La stuff (the album title was a knowing reference to 3 Feet…‘s game show).

Another feted rhymesmith stood behind Souls in the Hiero queue – an emcee known as Casual – and all the crew benefitted from producer/manager Domino’s input; so there was something for the band to build on, and a story to tell that showed they were part of a movement, not just Del’s mates latching on to his coat-tails, and therefore likely to fall by the wayside if his career faltered.

The group weren’t just propping themselves up on a diet of recently absorbed east-coast lyricism, either. While the sound that Souls essayed came as something of a surprise in 1993 to a rap fan conditioned to think of New York being about the wordplay and California as the home of the smoothed-out gangsta flow, there was a long-seated tradition of west-coast lyricism. In LA, Freestyle Fellowship and the Pharcyde had made their own waves, while Ices Cube and T were hardly an advert for the sing-song approach. And Cypress Hill’s deliberately enigmatic 1991 debut had people wondering if they were from the New York enclave of that name.

"Brothers been freestylin’ in Oakland since 1980," Tajai told me in an interview conducted during their first British tour in 2000. "Freestyling, writtens, battling, breakin’, graffiti – that shit doesn’t come from thinkin’, ‘Now it’s the ’90s, it’s time to be big.’ It takes 15, 20 years of workin’ hard at that shit. I don’t want people to think that it was suddenly like we on the west coast grew a lyricism limb."

And Souls had got a deal with the BMG/Zomba-owned Jive, which – despite a reputation in Britain that saw the imprint principally known as the home of page-three-girl-turned-pop-starlet Samantha Fox, and which would later make it the natural home for Britney Spears, ‘NSYNC and Justin Timberlake – was arguably hip hop’s leading label of the day. Jive never got the press or the kudos that attended a Def Jam, a Tommy Boy or a Death Row, but they’d been involved in hip hop for ages – Whodini were an early rap signing, their ‘Magic’s Wand’ a pre-Golden Age classic, while the label also released all the early work of gangsta pioneer Schooly D – and a look at the label’s hip hop roster in the early ’90s is like reading a who’s-who of the best rap talent alive.

The label had released all but one of the albums made by KRS-ONE, which until 1993 had all come out under the Boogie Down Productions name, and had also done two solo records by BDP’s D-Nice; they’d released all Tribe Called Quest’s albums, and were – at the time of Souls’ debut – readying the release of Midnight Marauders, which would solidify and intensify that band’s love affair with the kind of rock critics who barely listened to rap other than Tribe, De La and Public Enemy. The hypersyllabic tongue-twisting lyrical gymnastics – not to mention the kung-fu allusions – of Fu-Schnickens, and in particular the dazzling Chip Fu and his Looney Tunes flow, had helped pave the way for, first, Das EFX and, soon, would make aspects of the Wu-Tang Clan’s shtick a bit easier to comprehend; meanwhile, the band’s unlikely team-up with basketball superstar Shaquille O’Neal would lead to Jive getting to release a string of successful (artistically as well as commercially) albums by the hip hop generation’s biggest sporting icon. Jive had also proved they could get rap to go pop, without being too cheesy about it, in the shape of DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince, whose later chart-oriented fare (‘Boom! Shake the Room’; ‘Summertime’) might suggest otherwise, but whose roots in innovative and credible hip hop went deep and were established on Jive releases such as the great 1988 LP – hip hop’s first double-vinyl set – He’s the DJ, I’m the Rapper (bizarrely, recorded not in the duo’s native Philadelphia or hip hop’s New York heartland, but mostly in Jive’s studio in Willesden, north London).

Crucially for Souls, Jive also knew how to handle singular talents from the same northern Californian regional market. Too $hort had sold unfathomable amounts of records considering almost no-one outside the Bay Area knew who he was, and deals with Spice 1 and E-40 were in hand. The label seemed to have found a way of allowing artists to operate without the kind of heavy handed tinkering that so often attends corporate music business attempts at turning strong local followings into broader, if shallower, global ones – no doubt helped, in part, by having picked up these artists when initial independent releases had shown sales were

already picking up, and adopting a not-broke/don’t-fix approach. There can surely have been no other imprint better placed to take Souls’ promise and help them turn it into dollars and cents.

So SoM had the beats and the microphone skills to carve out their own niche; the promotion and marketing muscle of a well-placed major ready to feed their music into the system; the friends-and-family support network that also functioned as a means of signalling their bona fides to fans keen to check for any new rap act’s provenance; and they came from a culture that was strong, yet little-known, thus giving the group both a vibrant tradition to grow their talents within, and an exciting story to tell to the world’s press. The album title showed they even understood how to use an apostrophe – something that even the most cerebral of crews, such as the "MC’s" Ultramagnetic and Stereo, couldn’t manage. It was a strong package, but a lot of artists could say the same. Where many fell down was with that all-important first single, and of course, in those days when MTV and BET could be the difference between stratospheric success and ignominious failure, its accompanying video. Was this where the Souls story began to fall off the rails? The answer is an absolute and

unequivocal "no".

The album’s title track remains the song for which the band will forever be identified – the tune they won’t be allowed to leave a stage without playing, even if there’s rap gigs in the afterlife. It’s one of the greatest four minutes in hip-hop history, a magical and powerfully emotive combination of vocal dexterity and musical inspiration. It was definably and definitely all their own work – Domino wasn’t involved; the producer here was A-Plus – and, as a fascinating 20th anniversary interview by Emmanuel CM published earlier this year by XXL reveals, it had its roots in an earlier, different demo which meant a very great deal to the band. That emotional investment is clear and unmistakable, and it’s the secret sauce that fuels their masterpiece.

The video was every bit as inspired, too. Director Michael Lucero – a friend who the band got to know through his work with Del – did something that almost no-one in the pantheon of rap promo clips appears to have thought of: rather than delivering the sort of video that would have been expected for the first single by a new band looking to break through, initially, to the hardcore rap fan base, he upended convention and subverted the cliches with an approach that still delights with its euphoria-inducing embrace of the joy of doing something different. Indeed, the clip still seems almost giddy with the sense of how easy this was to accomplish.

Souls were from Oakland, as the opening spoken preamble made clear, and – the largely unknown-outside-the-Bay Too $hort apart – that meant that scenes of local ‘hood life would have, arguably, done more to emphasise the group’s "realness" than any other visual signifier while still being "different" – or, at least, different enough. Show rap fans that there were ghettos across the bay from San Francisco too, and that the guys there were keepin’ it every bit as real as their contemporaries in South Central or Crooklyn, and surely their path to acceptance would be smoothed.

Yet – apart from a very brief couple of scenes – the clip places the four-piece out among the pine trees, beside the crystal-clear rivers, and between the snow-topped mountains of Yosemite National Park; or on a beach, sand and waves replacing blunted homeboys and graffiti-drenched abandoned buildings for its backdrop. Here, it says, is a band that know of a different California – and a band who aren’t content to say the same old shit in the same old ways. To top it off, instead of the grimy chiaroscuros other directors favoured to stress gritty urban reality where rap was concerned, Lucero showed the mountaineering Mischiefians, alternately, in an almost pastel colour field of fecund greens against the bluest of skies, and pure, old-school black and white. OK, so it wasn’t quite Ansel Adams: but if you wanted to say, "These guys are really not

about to conform to any of your preconceptions, thank you very much," you couldn’t have come up with a more succinct visual means of doing so. The only thing missing, in retrospect, were the backpacks one might have imagined Yosemite hikers to have carried, and which would become the shorthand caricature definer of the type of hip hop Souls made in the years that were to follow.

The fact that it all fit with the sound of the record was of immeasurable help, too. The key samples used in 93 ‘Til Infinity are from two sections in the middle of a lengthy, slow, curious piece of instrumental music by a band led by the drummer Billy Cobham. After a brief stint as a member of Miles Davis’s never-ending mission to locate a new music in the

middle of jazz, funk and cut-up sound collages in the period immediately following Bitches Brew (both Cobham and Jack Dejohnette played on A Tribute To Jack Johnson, taking the place of Buddy Miles, who Davis had had in mind when he wrote the music), Cobham formed the Mahavishnu Orchestra with John McLaughlin and by 1974 was on to his second solo LP. (The first, incidentally, contains the tune ‘Stratus’ – another track that was used as the basis of an early 90s single by an idiosyncratic west-coast hip-hop outfit, though in the case of Massive Attack’s ‘Safe from Harm’, the coast was of England).

‘Heather’ sits in the middle of side two of Cobham’s strange, beguiling, vividly exciting Crosswinds, and anyone who picked it up post-Souls expecting to hear more of where the Oakland rappers were coming from would have had a surprise. The track floats, an ethereal drift of mood expressed as melody, more texture than rhythm; whether it’s uplifting, mournful, questioning, optimistic, relaxing, perturbing or all of the above is never resolved. It could be about a girl, but given the titles of other tracks (‘Spanish Moss’, ‘The Pleasant Pheasant’, ‘Flash Flood’) the track is probably meant to evoke the wind-blasted remoteness Cobham’s front-cover photo deals in – another aspect Souls and Lucero ended up referencing, whether consciously or not, with their choice of video location. It’s bookended by two tracks more obviously bristling with the kind of samples hip hop producers are supposed to favour – indeed, the title track (albeit with a singular rather than plural name, ‘Crosswind’), which follows it, had been used by DJ Premier on Gang Starr’s jazz-rap magnum opus Step In the Arena (it forms the main loop for ‘Here Today, Gone Tomorrow’ and may well be the reason why A-Plus sought out a copy of Crosswind).

Does any of this history matter? Would A-Plus, as producer, never mind his fellow bandmates, have been aware of any of it? To answer those questions in reverse order: probably not, and yes, absolutely. What makes the song so powerful, the aspect of it that gives it that enduring sense of other-worldliness and of meaning more than it ever says or includes, is the way it intuitively understands and respects the many different contexts in which it exists. It’s not just about some 18-year-olds finding a record made before they were born and stealing its sound: it’s about the magic of musical creation and composition, where so much that may never have been consciously intended winds up in the grooves as the idea transitions from conception and invention through performance into the historical artefact created by the recording process. It sounds like it exists in a place that can’t be explained by examining the lives and work of the four teenagers from a city in northern California who made it, because it also carries all that history of invention and reinvention that Cobham’s record was borne out of. And it sounds mysterious because it embodies and exists because of the inherent and intrinsic mystery of musical creation.

Also: unlike many of the "classic" samples in rap history, the loops Souls used come from way out in the middle of the track, not the intro – and to fit the markedly snappier tempo, they need the original Cobham album to be played at 45 rather than 33. Finding these pieces of sound wasn’t as easy as dropping the needle on an unfamiliar cut and snaffling a snarl of a drum loop – ’93 ‘Til…’ was a track built by someone for whom that Cobham cut must have held some real personal meaning, or who had at very least paid more than a passing interest to it as they scanned the album looking for more of what Primo had found there in 1991. Even after the sample was isolated, chopped out of its original context, speeded up, looped, and added to a completely different drum rhythm, it still retains all of the sense of awe-filled mystery and beguiling if enigmatic promise that Cobham’s patient slow-burn moodscape encapsulates. To those who say sampling is artless theft, I hereby present, as the first exhibit for the defence, ‘Heather’ and ’93 ‘Til Infinity’ – a case-study in how the technique can, when carried out by artists working at the height of their powers, add substantially to both the new work and the ones it’s made up from pieces of.

Of course, if the album had only really had the one good track, we wouldn’t be talking about it 20 years later. 93 ‘Til Infinity would be a standout on anybody’s record – put it on any classic hip hop album and it would have been one of the best things on it, perhaps the best. It dominates the album that took it as its title, but a significant number of the other 12 tracks (the album has 14, but the last one is just an outro rather than a proper song) run it close.

Opener ‘Let ‘Em Know’ sets out their impressive stall, Domino ripping Ronnie Boykins’ bassline from the first track of George Benson’s 1964 debut album into a fire-breathing cousin of Low End Theory Tribe before the drums clatter in and the emcees pour over the track like the water in one of those Yosemite rivers, flowing over the beats and deep into the cracks and crevices between the angles of the sound. This is writing and performance that goes beyond poetics, and belies the fact that the band members were barely out of high school: check Phesto’s bravura final verse, where metre and line structure play second fiddle to the beat’s iron rule: "Here I go again!/ Return of the Jedi, red eye/ Use my lightsabre…" And he’s off, ricocheting around inside the track, images colliding with the beat, the only weakness being ours, the inability of even the most furiously concentrating listener to keep pace with it all. The writing throughout is formally inventive and uncommonly dextrous – sequences such as A-Plus’s "I’m leavin’ niggas stranded/ Man, that’s how I planned it/ Landed blows with my random flows/ And it goes… a little something like this" on ‘Batting Practice’ often slide by without attracting attention, simply because of the embarrassment of rap riches on display.

Del drops in with ‘Make Your Mind Up’ halfway through side two, and two productions midway through side one, all of which stick to the sample-heavy melodiousness his own record had brimmed with. Although ‘That’s When Ya Lost’ became the second single from this LP, the pick of the three is ‘A Name I Call Myself’, with a lovely Benson guitar lick (this time from a Freddie Hubbard album) turned into a woozy melodic backbone for a formidable collage of samples which, whether cleverly or due to sample-clearance problems history as yet has not recorded, ignores the Mary Poppins reference in the song’s title. Domino’s work (four songs and the outro) is jazzier and often features more scratching. Casual produces ‘Batting Practice’ and another Hiero member, Jay-Biz, co-produced ‘Dissishowwedo’ with Domino and built the beat for ‘Limitations’. The other four came from A-Plus. Despite this, the record has a homogenous sound and a consistency of approach that belies the collective nature of

its creation. Souls were the focus and the named artist, but the Hiero ecology was working as one. It’s a remarkable achievement.

That they cast a long shadow is not in doubt. J.Cole and some-time Tribe member Consequence (with Kanye West) are among those who’ve recorded their own versions of ’93 ‘Til Infinity’ (as ”Til Infinity’ and ’03 Til Infinity’ respectively) while, in sampling it to close the song ‘Keep On’ on his 2012 debut album, House Shoes did more than just tip his hat at Souls, he borrowed some of what the song, and this album, has come to mean in the hip-hop heartland. Moreover, their sound changed hip hop’s trajectory, inspiring others not just to flow differently, but to remember to prize individuality over everything else – no matter where you were from. The record is even in the process of getting its own documentary film.

So why didn’t it end up in more homes? Why are Opio, Phesto, A-Plus and Tajai still out doing unfeasibly long tours of venues you’d have thought far too small to accommodate the numbers of fans such capable artists would by now have attracted? Why did they become one of those bands who are perhaps revered more by other musicians than by listeners – musicians whose influence is felt more often than their records are actually heard? The politics of the record business seems to be the most-cited reason, but that can only tell a part of any story. Luck, too, always needs to be on your side, and Souls clearly had less of that than seems fair or adequate. But to these ears, there may be something at the heart of the record that helps explain it a little better. Or, rather, something that should be there, but isn’t.

As breathtaking and exciting as the form and sound of their music was, and as intricate, intelligent and daring as the construction of their rhymes and the delivery of them across the beats had been, there’s little in what Souls say on this record that can match up in great-leap-forward terms. Despite what ’93 ‘Til Infinity’ sounds like (or what the video looks like), at the end of the day it’s just another song about drinking, smoking and shagging. True, that needn’t be a problem – and in Opio’s opening verse he references another band of Californian sonic visionaries whose best-known songs also tended to stick to the reliable pop staples of relationships and admiring the opposite sex, even as their soundscapes were changing the world ("The weather’s heat in Cali/ Gettin’ weeded makes it feel like Maui/ Now we/ Feel the good vibrations"). But it’s the one area of the record that lags behind, so perhaps it’s the most plausible explanation for why such a staggeringly adventurous and potentially accessible group failed to cross over.

"Emcees should know their limitations," they rapped here – and over the years there’s been so many artists who’ve given so much cause for you to wish that those words had been taken to heart across the genre that you kind of forget that Souls were the first to ignore that very piece of advice. Their limitation here was life experience: they were kids, and hadn’t had very much of it yet. So they wrote, as one is always advised to do, about what they knew – girls, hanging out, how great they were at rapping: all the same stuff everyone else in hip hop was writing about.

That this wasn’t anywhere near as vast or all-encompassing or ambitious or limitless in scope as the sounds on the records they made was hardly their fault – but it’s the one piece of the puzzle that doesn’t quite fit.

If they’d taken themselves at their word, and chosen to operate within their thematic limits, the only way would have involved scaling back on the scale of achievement they’d reached on the sonics. They’d have had to have toned down all the other parts of their music that were so extravagantly advanced. The whole style and approach would have had to change, leaving instead a bland, grey record lacking in all the brave and brilliant things that makes 93 ‘Til Infinity so wonderful. They might have been an easier sell, and they might have achieved riches and fame beyond their wildest dreams: but they would never have begun to touch the peaks of greatness they seemed to effortlessly scale on this wonderful record.