Looking at it logically, there was no way Son Of Bazerk ought to have been able to fail. The Long Island group were signed to the label run by Hank Shocklee and Bill Stephney, two members of the Bomb Squad production team behind the world-changing early releases by Public Enemy. Hank and other Bomb Squad cohorts – his brother Keith, Gary G Wiz and Carl Ryder (the production name used by PE’s Chuck D) – were manning the boards, and they made SOB’s debut album right in the middle of one of the hottest streaks in musical history. Furthermore, the Long Island group’s music – a fierce, raw take on hip hop, not so much seasoned as drenched in lashings of gutbucket soul – had not just the provenance but the sustained attack to appeal to the burgeoning global hip hop audience of 1991.

This debut brims with invention, its muscular musicality precision-tooled to get under the skin of folks who might have dug the attitude of PE but were left cold by the sometimes machine-like aspects of the sound; it also effortlessly managed to connect the new style to the roots of black American pop in a way that you’d have thought could easily have opened up hip hop to listeners weaned on soul’s traditions and jazz’s formalised stressing of inspiration and innovation. Yet this astonishing record sank more or less without trace. There are reasons for this – and some of them, with the benefit of hindsight, are teeth-looseningly obvious. Yet Bazerk, Bazerk, Bazerk is a record that still, 25 years on, sounds like it’s crash-landed on your stereo from some indeterminate and unknowable point a long way in the future.

Perhaps aptly for a record apparently built out of a series of high-energy head-on collisions between different sounds, styles, ideas and musical genres, the line-up of the people who made Bazerk, Bazerk, Bazerk is a tad complicated. The group was called Son Of Bazerk after its leader, a gravel-throated rapper who attacked the microphone like a boxer unleashed from a lengthy spell in a particularly austere training camp. The back cover shows four other members – Daddy Rawe, Almighty Jahwell, Cassandra aka MC Halfpint, and Sandman – with the latter likely to leave even the most attentive listener unable to locate as audibly present on the record. The front of the sleeve claims the album is the work of "Son of Bazerk featuring No Self Control and The Band": perhaps inspired by Chuck D’s line in ‘Bring The Noise’ where he mentioned that "Run-DMC first said a DJ could be a band", SOB’s DJ was called The Band, though it’s not clear whether or not Sandman and The Band are one and the same. (Just to complicate matters further, the small print on the back cover credits the DJing on the record to PE’s Terminator X and Kamron of SOB’s labelmates, Young Black Teenagers, while in more recent interviews, the group have credited some of the scratching to Johnny "Juice" Rosado, Kamron and The Band, but none to Terminator X.) As for "No Self Control", this is supposed to be a collective name for the members of the group who weren’t Son of Bazerk himself – but it’s probably best to interpret it as part description, part warning. Bazerk, Bazerk, Bazerk has many virtues, but restraint is not among them.

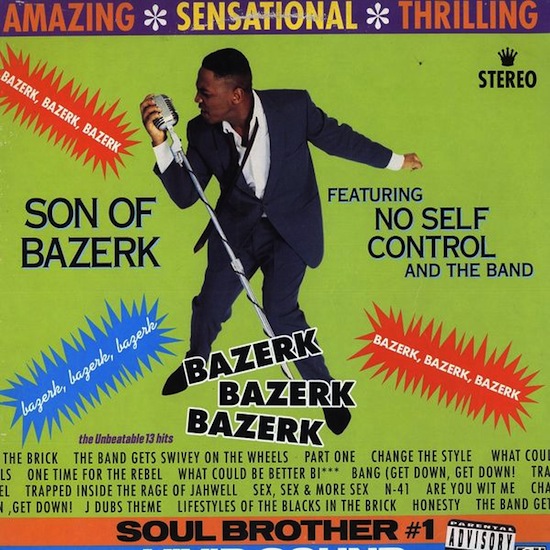

That album sleeve – our only clue, back in the pre-internet era when an artist wasn’t having hits, in heavy rotation on MTV, and being interviewed by the handful of music magazines that bothered to cover rap – doesn’t even give you much idea that the record inside is a hip hop LP. The front cover is a pastiche of James Brown’s Please, Please, Please, Bazerk in sharp suit, unknotted skinny tie swinging around his midriff, jousting with a vintage mic on a stand. The image is mirrored on the back cover, where the list of "musical and lyrical influences" reads, in full: James Brown, The Moments, The Stylistics, New Birth, Kool & the Gang, Barry White, Grand Master Flash, Melle Mel. If you had taken that at face value, and tried to imagine what a record made by people who cited those eight artists as influences might sound like, you still wouldn’t have been able to guess at what was about to happen when you dropped the needle on side one of Bazerk, Bazerk, Bazerk (which, just to keep you on your toes, is mislabelled as side two). But it would have got you part of the way there.

They’d begun rap life as the Townhouse 3, in the Long Island town of Freeport, and were considerably more than the bit-part players in a long-forgotten regional scene today’s scant online information might suggest. It was Son of Bazerk who introduced Chuck D to Flavor Flav, and, according to the hip hop writer Jesse Serwer, whose researches into the history of Long Island hip hop led him to play a part in the group’s 2010 live comeback, Bazerk was the man who gave Flav his first clock. For his part, Chuck has talked of Bazerk not as a protégé but someone who helped shape his own art. "Bazerk was a very big vocal influence for me," Chuck told me in 2003. "He helped me understand what I could do. He had a God-given voice."

The first time that voice was heard outside the Long Island neighbourhoods PE and their retinue came up in was when Son Of Bazerk’s first single, ‘Change The Style’, came out in December 1990. Another retro-styled sleeve this time at least offered a tangible link to Public Enemy – a strap across the top reads "Flav-A-Flav-A-Flav Presents" – but the record was unlike anything heard before, in hip hop or in music generally. It starts with a sample of the guitar lick introduction to the Temptations’ ‘(I Know) I’m Losing You’ before slamming hard into the verse, Bazerk growling a lyric that’s as much part of the scatting tradition as it is a straight-ahead rap performance. The beat – rubbery in bounce, almost jaunty in melodic playfulness – is complicated but not immediately striking as extraordinary. It’s what happens when the group gets to the chorus where the track signals Son Of Bazerk’s inclination towards iconoclasm.

If hip hop’s sample-based methodology is, as has been argued by some of those who’ve analysed it as a postmodernist art, defined by breaks and ruptures, then ‘Change The Style’ is arguably the perfect example of the form. There is no pretence made at smooth transitions: instead of a hook that fits with the verse, SOB and the Bomb Squad snatch all the music of the verse away and replace it with a huge lump of Yellowman’s 1983 dancehall reggae track, ‘Nobody Move, Nobody Get Hurt’. There’s no continuity – of tempo, key, lyrical theme. And after a few seconds, we’re back into verse two, the same music as the first verse, before smashing into a doo-wop hook the next time around. For the finale, the changed style flips us into punk, via a Bad Brains sample. It’s less a single than a high-speed multi-genre pile-up on the musical motorway: sonic carnage, aural confusion, a record made by people who knew what the rules were, but were going out of their way to not just break them but leave them looking hopelessly outdated and no longer fit for purpose.

You could have argued this was going too far, or that the abruptness and incongruity of the transitions between styles was evidence of a lack of skill. But listen to verse two, where a bar of Bob James’ ‘Nautilus’ is woven in seamlessly after Bazerk demands his comrades "hit me with a hit from the past". The very deliberate nature of the lack of continuity becomes a signature: and, after time spent thinking about it and delighting in this record’s blunt repudiation of formalities, one reaches the conclusion that its festishisation of the abrupt jump-cut in itself achieves a kind of formal unity. Hip hop promised unlimited possibilities, where different genres could coexist via the sampler and the turntable in ways undreamed of before, and where the only restrictions were the ability of the artist to imagine something, and the ability of the audience to let the artist explore their unprecedented freedom. This was hip hop at its most outré, but at the same time, ‘Change The Style’ is what this music was always supposed to be.

Inauspiciously, if perhaps understandably, the single failed to blaze much of a trail: so when Bazerk, Bazerk, Bazerk arrived the following May, the marketplace was hardly primed. Those who paid attention to such minutiae would have recognised the imprint (the MCA-funded SOUL – Sound Of Urban Listeners) as Shocklee and Stephney’s company, and may have picked up on a thematic link between this album and the label’s first (Young Black Teenagers’ self-titled debut had arrived in a sleeve that pastiched the first Beatles LP cover). But it wasn’t a particularly obvious addition to the shopping lists of PE fans, and the connections to such an agenda-setting band were (deliberately?) downplayed.

Fundamentally important – and perhaps initially confusing; maybe, in terms of the album’s opening track, actively off-putting – was the record’s place in the Bomb Squad’s discography. In 1990 the production crew had helmed Public Enemy’s masterpiece, Fear Of A Black Planet, Ice Cube’s solo debut, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, and Bell Biv Devoe’s Poison. The latter record at first glance appears the key one in shaping SOB’s rap-soul hybrid, though in truth there had been an even earlier parallel when the Bomb Squad (or, at least, Hank and the other backroom Squad member, Eric "Vietnam" Sadler) worked on Alyson Williams’ ‘Sleep Talk’ single, effectively minting the hip hop/soul hybrid that Puffy later built into a global commodity. But it would be the Cube LP that had the most direct, and perhaps initially problematic, impact on the potential audience for Son of Bazerk.

According to Shocklee, the track that became both ‘AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted’ and Son of Bazerk’s ‘The Band Gets Swivey On The Wheels’ was intended, at the outset, for the Bazerk album. "One of the things that I never wanted to do was to have one artist’s identity the same identity as another artist," Shocklee told me some years ago. "I’ve always wanted to make sure that every artist had its own identity. That, to me, is where the real work comes in. But at that time, there was things that was just being crossed." The end result was that SOB’s debut kicks off with the group appearing to offer their version of a song Cube had used to announce his departure from NWA and the start of his solo career the previous year.

Back then, hip hop cover versions were unknown: even by 1993, Snoop’s cover of Slick Rick was controversial. This wasn’t the same track as ‘AmeriKKKa’s…’ – the vocals are completely different, there’s no similarity to the arrangement: it’s just very clearly the same music playing in both songs’ verses – which, in a way, was possibly even more contentious. Again, the lack of direct channels of communication from the band to their potential fans needs to be borne in mind: there was no social media for them to use to explain themselves, no website where they could put their views forward for evaluation, and in the absence of media coverage, all fans had to judge their intentions by was what was contained in the grooves on the LP. So here was a new band, releasing an album in the middle of hip hop’s most concerted period of constant and unrelenting innovation, and sounding like they were guilty of committing the music’s cardinal sin – biting.

The group might well have decided to omit the song from the album, but that would have deprived us of arguably the best part of a record that is characterised throughout by a relentless, punishing pursuit of something uncompromising and new. Knowing he can’t let the obvious go unacknowledged, Bazerk kicks it off with something between a sly dig and a doff of the cap – "Sling me that Ice Cube track": it’s effective, but perhaps downplays SOB’s legitimate claim to the song by playfully suggesting they’d nicked it from Cube.

Within seconds, though, it’s clear we’re listening to an entirely different kind of music. After the sampled brass squeal builds under Half Pint’s excitable exhortations, Bazerk jumps in with a power and a sense of I-don’t-care-what-you-think individuality and vocal personality that immediately sets him apart – from Cube, from Chuck, and from the rest of hip hop in general. What follows is three and a half minutes of lightly organised chaos, with hook sections truncated by single measures to keep the listener guessing, and layer after layer of samples, genres and styles added on top of each other until the whole thing collapses under the weight of its own excellence. There’s a pastiche 60s pop show video which is just as brilliant, in which we see a man scratching a record while wearing oven gloves in between glimpses of faux Supremes, Fabs and Bazerk as James Brown. It’s like hearing – and seeing – four decades of black pop music compressed and condensed into a single, astonishing song.

You can’t expect an album to keep pace with such an extraordinary opening, yet Bazerk, Bazerk, Bazerk barely pauses for breath. ‘Part One’ kicks off with another JB vocal riff. A kind of fanfare without brass and a chaotic rewind is executed just in case, a few seconds in, you were beginning to think you knew what was going on; then, just past the two-minute mark, the entire track abruptly alters, a completely new beat at a slightly different tempo is introduced, and the lyric heads off in yet another direction. In this context, ‘Change The Style’ suddenly comes in to perfect focus: the third track on the album, its loose assortment of musical fragments perversely makes it an effective and surprisingly sturdy bridge between the mayhem of the first two tracks and the apparent straightforward simplicity of the next cut, ‘One Time For The Rebel’, a tribute to Chuck D set to a hulking great chunk of ‘Whole Lotta Love’. For a brief moment we’re on something like familiar turf – even if it wasn’t so familiar from its source material, this would still sound like music of a kind we recognise. That is, until the hook – several voices bellowing "Five, ten, fifteen, twenty, twenty-five, thirty" for no immediately apparent reason.

It’s only with the fifth song, ‘What Could Be Better B****’ – that we encounter something ordinary, but its meandering is soon ended by the utterly bonkers ‘Bang (Get Down, Get Down)!’ Layering conga drums, sweeping pop-orchestra strings and rubber band bass over a driving, uptempo pulse beat, the verses are sung while the hooks, from Bazerk, are ragga-tinged raps recorded as if down a long-distance phone line. Throughout the track, there’s someone chattering and shouting in the background, the words rarely getting close enough to the surface to be properly heard, never mind consistently understood. Like the best kind of chaos, it’s a bit confusing, significantly compelling and utterly exciting.

Side two is a little less astounding, thought these evaluations are of course comparative. It’s not that the ideas are any less sonically extraordinary, just that there are a preponderance of songs with only one major musical element compared to the multiple and often jarringly dissonant selection of ideas that appear in five of the six tracks on side one. Even then, it’s not by any means simple. Jahwell’s solo cut, ‘Trapped Inside the Rage of Jahwell’ may be a single verse delivered over shuddering bass and sound effects akin to those used when Frankenstein pulls the lever to spark life into the monster in the classic black and white movies, but it starts off with a horn-driven riff for an intro which runs at a completely different tempo to the rest of the song. ‘Sex, Sex & More Sex’ is just one loop – one of the few moments here where the backing track sounds like something you could imagine hearing on a Public Enemy album, even allowing for the fact that Public Enemy are the only possible reference point you could point to when trying to suggest records Bazerk, Bazerk, Bazerk resembles – but the lyric dissolves in and out of being an actual rap: somewhere in the middle it becomes a disconnected kind of conversation between Bazerk and his bandmates, phrases splattered across the beat without any apparent attention to rhythm, only for the rest of the part-expressed thought to be delivered precisely and dextrously in complicated, syncopated, gloriously swinging patterns.

‘N-41’ similarly features odd vocal patterns over a simple beat (a single drum machine loop) but it sounds like there’s a party going on in the background: it’s only ordinary when compared to the standards Son Of Bazerk set elsewhere on the record. ‘Are You Wit Me’ and ‘J Dubs Theme’, too, are simple enough to understand, but exceptional performances: the former has Bazerk declaiming an improbable childhood autobiography over a sleazy, slouching, chopped-up sample from Albert King’s ‘Cold Feet’ (patterned on the 1989 underground rap hit ‘I’m Not Playin”, by Ultimate Force); the latter couples an almost Soul II Soul-ish swing-style beat and bass line with sung lyrics and ragga chat in place of hooks. If these tracks give the impression of conventionality it’s only because each song relies on a single dominant sonic motif: these are still extraordinary pieces of pop. And any sense of the group tiring before the finishing straight is shattered with the final two tracks – ‘Lifestyles Of The Blacks In The Brick’ returning the album to the pedal-to-the-floor pace of side one, and ‘Honesty’ rounding the whole thing off in another blast of joyously unconstrained genre-boundary obliteration.

That such a deliberately, calculatedly different-sounding record failed to find an audience is perhaps unsurprising. Your correspondent counts himself among those unable to see the wood for the trees: reviewing the record in Hip-Hop Connection, I struggled to understand what I was hearing, and failed to appreciate the wider context the album was created within. Colleagues elsewhere proved similarly ill-equipped. Sales were less than stratospheric, and the chances of unsold copies getting a boost from the remainder bins wasn’t helped by the curious decision in 1992 to include the album’s weakest song as the group’s sole contribution to the soundtrack to the movie Juice, thus ensuring that anyone picking up that LP to get the new Rakim, Big Daddy Kane or EPMD tracks missed the opportunity to hear something startling and inventive which might have pointed them in the direction of Bazerk, Bazerk, Bazerk. Even the release of a second single appears to have been an opportunity botched, with ‘Bang (Get Down, Get Down)!’ given a-side billing but no video, surely partially explaining why ‘The Band Gets Swivey on the Wheels’ clip was so little-used, given the likely reticence of TV shows to play a video for a b-side.

It probably also didn’t help that the group had no apparent interest in political material. ‘Lifestyles of The Blacks In The Brick’ comes close to the kind of street narrative that, post-NWA, was coming to dominate hip hop fans’ expectations of what the music was supposed to be doing, and the non-specialist fans who lauded PE for their social commentary might well have found fault with Bazerk, Bazerk, Bazerk‘s disinclination to engage with those themes. Yet again, the group’s refusal to conform to expectations may have been their undoing, even though it put them ever closer to the heart of what their art form was supposed to be all about.

Backroom shenanigans doubtless kicked in following the album’s poor retail performance, and a precise apportionment of any blame is unlikely to be made. In recent years Bazerk has spoken in somewhat less than glowing terms about Hank Shocklee, suggesting the putative Bomb Squad leader’s role in the SOB records wasn’t that of the main driving force history has tended to accord him. Rosado, too, has downplayed Shocklee’s involvement. There was clearly some animosity, which may have helped to explain why the group’s career went off the rails following the album’s commercial failure. Bazerk says he recorded a second LP which Shocklee rejected; then a third album which also remains unreleased. At least one track has emerged in recent years where the lyric implies it was either recorded in, or intended to be released in, 1994. By then, though, there was no SOUL to release it: the label only ever put out four albums (debuts from YBT and SOB in 1991, the Juice soundtrack in 92 and the brilliant second album from the Teenagers, Dead Enz Kidz Doin’ Lifetime Bidz, in 1993), Stephney had left the set-up in 1991, and Hank was soon to set up another imprint, Shocklee Entertainment, with Keith.

For his part, in an interview eight years ago, Shocklee spoke effusively of Bazerk’s presence and potential, suggesting only that his writing process may have contributed to the lack of a follow-up to the debut album. "Bazerk coulda been Wilson Pickett – he coulda been Otis Redding," Shocklee told me. "He could’ve been James Brown. He was a trendsetter. His whole style and his charisma was, to me, so revolutionary and so new, because he embodied the 60s soul with the rap and funk and the feel of today. Son of Bazerk’s only problem was that he didn’t write a lot, so it took him an incredible amount of time to come up with a song. That was his only downfall." The same point was made separately and independently by Chuck D ("He never took the time to write well, or to have things written for him," Chuck said of Bazerk. "He’s like what you’d call Sly Stone – you want to walk behind him with a tape recorder and just go, ‘Man, could you just say this?’").

In the early years of the 20th century, Chuck’s online label, SlamJamz, released four SOB tracks that may have been intended for a second LP: they’re a shade more conventional but still feature that blistering Bazerk belligerence. Halfpint – who works as a teacher in Roosevelt, Long Island – published three further tracks, along with associated photos, on her YouTube channel in 2009. The following year, Daddy Rawe, Half Pint, Jahwell and Bazerk reunited and made a new LP with Johnny Juice as producer. Well Thawed Out was released digitally and as a CD on Slamjamz. There’s been talk of a third LP, RaWaLiTy, for some time, with a track apparently taken from it (‘On The Verge Of An Ass Whippin’) released in 2012, but as yet there’s no sign of the completed full-length. The group’s Facebook page is regularly updated and Rawe is due to release a solo album imminently under the name Pops Smash. It’s a racing certainty they’ll never see the financial rewards such brilliance as they displayed on their debut surely merits: but you wouldn’t bet against these single-minded musical revolutionaries returning with something startling, unexpected and very, very special.