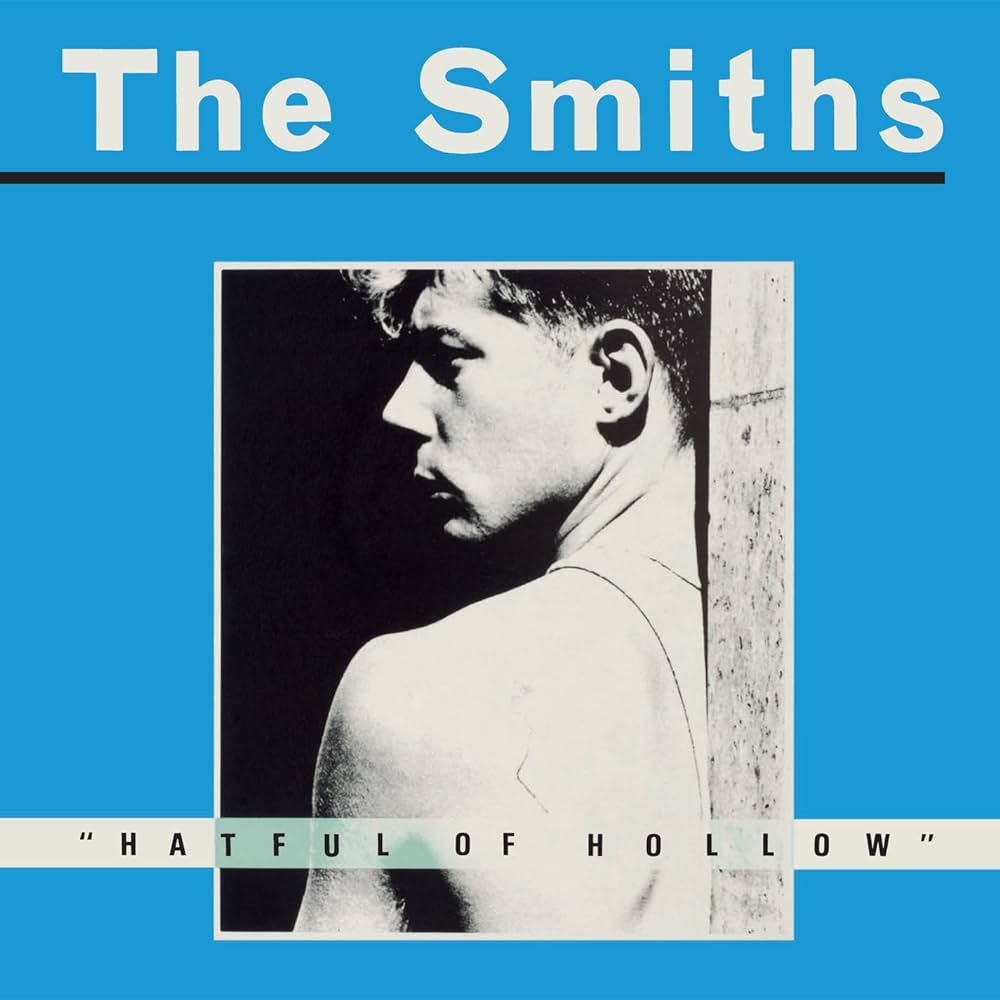

Hatful of Hollow is The Smiths’ best album because it’s their most innocent. This may seem an untoward claim for this most knowing and self-aware of bands, with Johnny Marr steeped in music history beyond his years and Morrissey seemingly born jaded. Yet this collection of standalone singles and dashed-off radio sessions possesses a freshness and immediacy that got lost on The Smiths’ gloomy, overcooked debut and buried on 1985’s morose, muffled Meat Is Murder. Hatful Of Hollow captures this mannered, doleful band at its most exuberant and joyful – nothing sounds overly deliberated over among these odds and sods. There are fewer guitar overdubs and no keyboards, the rhythm section sounds like it’s making an inspired first grab at the tracks, while Marr spins out sparkling riffs seemingly at will (better songs would kill for the intro to ‘Girl Afraid’). An almost callow Morrissey, meanwhile, articulates a wisdom and wit that hasn’t yet descended to the novelties which deface more obvious ‘best album’ contender, The Queen Is Dead (or connoisseur’s choice, Strangeways Here We Come). Lines like “No, I’ve never had a job because I’m too shy” are perfectly poised between precious and humorous. So, Hatful offers a route to recapturing The Smiths as they were when they first entered public consciousness: cockily charming, curiously ingenuous, alive with possibility, not pinned and mounted (like a butterfly).

Open-endedness isn’t the same as tentativeness, however, and Hatful’s indeterminacy derives, paradoxically, from The Smiths’ unusually acute sense of self. These early songs all address the experience – and demographic – of youth: provincial, awkward, un-sporty, haunting humdrum towns, old grey schools, rain-drenched streets and bedroom havens full of records, books and dreams. Because for all of youth’s trials, nothing has been determined yet: neither career, personality, nor – the elephant in the bedroom – sexuality. Despite its oafs and authoritarians, the world beyond the parental home is all potential, paranoias unconfirmed, hopes not yet dashed. A line like “Dreams have a knack of just not coming true”, doesn’t disguise the optimism behind The Smiths’ performative pessimism, and ‘dreams’ recur throughout Hatful Of Hollow. It was The Smiths’ ability to capture not just youth’s awkwardness but its aspiration – in the music’s elegance as well as the lyrics’ defiance – that endowed not just the shy kids with coolness but the cool kids with sensitivity. Non-prescription glasses, flat-tops and old-men’s overcoats – with a book in the pocket – ruled the indie 80s.

As much as Morrissey fancied himself a spokesman for this demographic – “I am the son and heir of a shyness that is criminally vulgar” – he also shied away from it: “I am the son and the heir of… nothing in particular”. The band’s first single, ‘Hand in Glove’ has all the pizzazz of a manifesto – “the sun shines out of our behinds” – celebrating the band, their misfit fanbase and a working class marginalised in post-industrial Britain: “we may be hidden by rags but we’ve something they’ll never have”. Yet the song’s flamboyance ducks into diffidence – “I know my luck too well / And I’ll probably never see you again” – while the homoeroticism slips away from the party. This hide-and-seek was the early Smiths’ metier, of course. We’ve a fair idea about the ‘it’ that’s caused the bother in ‘What Difference Does It Make?’, but none about who it’s addressed to: a male friend, a female lover, even a male lover? “Your prejudice won’t keep you warm tonight”, Morrissey chides, the Hatful version splendidly scrappy in all senses, with drummer Mike Joyce absolutely lunging at his kit. There’s neither self-pity nor mercy in this performance. On a fleet-footed studio take of ‘Handsome Devil’, the devilry is in the detail: title and verse promising perversity but then pivoting at the chorus to the loutish “let me get my hands on your mammary glands”. While this renders the taunt of “a boy in the hand is worth two in the bush” a tease, the presentation of sexuality as indeterminate – fluid – made The Smiths rather more radical than some of their more explicit peers.

Far from this indeterminacy being a flaw, then, the interplay between specificity and mystery powered the early Smiths (alongside that underrated rhythm section). These songs are finger-smudged with detail but fogged like a windowpane on a rainy evening. Proclamation is followed by equivocation: “this is true and yet it’s false”, “so wrong” but “half-right”, or “I’m not happy and I’m not sad”. Zoomed-in detail is followed by tracking-back distancing: “sore lips” from kissing on the “iron bridge” in ‘Still Ill’ culminating with “does the body rule the mind or the mind rule the body? I dunno”. The pitfalls of spelling things out were revealed on the debut’s ‘Miserable Lie’ and ‘Suffer Little Children’ and would be run into the ground on the gratingly earnest title-track to Meat Is Murder the following year. If summer 1984’s ‘Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now’ initially seemed self-parodyingly literal, time has revealed its layered complexities. Morrissey’s lyric dolefully rues unemployment, while rejecting the contemporary cult of work: “I was looking for a job and then I found a job / But heaven knows I’m miserable now”. This indeterminacy captures the 80s at its cusp, as refusal of Thatcherite austerity turned to reluctant consensus amid economic recovery (however unevenly distributed). This was paralleled by music’s pivot from post punk’s Euro-inspired greyness to new pop’s soul-inflected brightness – but which Marr declines to choose between. So, while the guitars are as chiming as jangle-fetishists could demand, the song’s introduction interpolates Sister Sledge’s 1980 disco cut ‘Easy Street’. Amid Thatcher’s nationalist chauvinism and the repression of Black music following Disco Sucks, this was a political statement in sound as much as sentiment.

This is bitterly ironic given Morrissey’s future flirtation with little Englander racism, a post imperial melancholia that, only hinted in The Smiths, would see the solo Morrissey shift from open-endedness to close-mindedness, life-affirming to life-denying. The Smiths appeared as anti-80s in their politics as their style – monochrome to the era’s Technicolor, retro to its futurist, downbeat to its upbeat. Yet it wasn’t just The Smiths’ drum sound that was closer to the mainstream 80s than it seemed at the time, that defining indeterminacy affected their personal politics too. The urgently ungainly ‘You’ve Got Everything Now’ bemoans school bullies turned loadsamoneys (with inevitable homoerotic overtones and a brilliantly undanceable beat). But what once seemed like a charming return of the repressed now comes across as vengefulness, chiming with the competitive individualism of the Thatcherism it ostensibly opposes: “I was right and you were wrong”. It also chimes with Thatcher’s claim to be the underdog biting back, a disingenuous distortion of power relations whether essayed by a Prime Minister, an indie celebrity, or his affluent cohorts on the contemporary far right.

If Morrisey’s Achilles heel was always his misanthropy, Marr’s was his muso tendency. Like his collaborator, Marr simultaneously courted and rejected the role of standard-bearer, in his case for jangle pop, deliberately rendering his style indeterminate. Yet in these early days, Marr’s muso ambition was contained by the 3-minute pop-song, post punk orthodoxy, and Morrissey. Unique not just to Hatful, ‘This Night Has Opened My Eyes’ is a perfect balance of sophistipop luxury and post punk austerity. Marr’s syncopated guitar part (in the left channel) is both exquisitely tasteful and tautly economical; his arpeggiated part (right channel) knows when to step forward and when to stand back, with the parts immaculately, imperfectly, conjoining at the one minute mark. Joyce and bassist Andy Rourke seamlessly entwine with Marr here – their playing expressive but empathetic – as, in his own peculiar way, does Morrissey. His lyric is a fragmented narrative from an imaginary kitchen-sink drama – related but not identical to A Taste Of Honey – simultaneously dreamlike and grainy with detail (the river the colour of lead; the baby wrapped in the News Of The World), souring but not curdling the music’s beauty. While the slick B-side version of ‘Back To The Old House’ owes much to ‘This Night’, the Hatful take is a stark acoustic arrangement which Marr manages to make lush – exquisitely matched by Morrissey’s elliptical lyric. With words and music evoking the equivocal pull of the past – “I would rather not go… I would love to go back” – the track is wistfully melancholy while still avoiding morbidity. Providing the best ending to any Smiths album, the fragmentary ‘Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want’ is the perfect representation of the Morrisey/Marr partnership at its fullest functionality. With Marr starting on acoustic, adding oh-so-delicate electric, then culminating with an orchestra of serenading mandolins, it’d be pure MOR indulgence were it not for the track’s brevity and Morrissey’s asperity. The lyric’s moroseness is almost humorous, but its hope is luminous, suffused with a yearning that – dovetailed with the dreamy backing track – is touchingly ingenuous.

One of few early Smiths songs to defy the three-minute edict, ‘Reel Around The Fountain’ directly addresses the subject – and the subject’s loss – of innocence. Yet in marrying what could be a skin-crawling tale of paedophilia to potentially saccharine music (derived from James Taylor’s version of ‘Handy Man’), sweet and sour coexist without either flavour dominating. Although the elliptical narrative also helps – how do you reel around a fountain? – the later album version, slavered with Paul Carrack’s prettifying keyboards, is an altogether queasier affair. Hatful’s other epic, ‘How Soon Is Now?’ was always a risky reassertion of rockism at new pop’s peak, a sludgy, swampy behemoth that borders blues-rock atavism, replete with screaming slide-guitars. Yet Marr’s cock-rock feint is undercut by Morrisey’s plaint of erotic failure – alongside his disdain for matching lyric to music. “When exactly do you mean?” is almost comically uncadenced. If the pair’s pitfalls complement each other on Hatful, ‘How Soon Is Now?’ was a harbinger of future division, the band’s attempt to repeat the formula on ‘Shoplifters Of The World Unite’ three years later the sound of agendas clashing.

Coming from a time when The Smiths were still the gawkiest last gang in town, Hatful Of Hollow boasts what are arguably their two definitive tracks. ‘William, It Was Really Nothing’ is another kitchen-sink narrative – loosely based on Billy Liar – and another triumph of indeterminacy, its rainy-day wistfulness alternating with convention-rejecting waspishness – marriage as containment of both sexuality and personality. While this is a radical queering of kitchen sink verities, even in the 80s you couldn’t miss the misogyny that makes ‘William’ a second-person take on Elton John’s ‘Someone Saved My Life Tonight’: “How can you stay with a fat girl who says / ‘Would you like to marry me, and if you like you can buy the ring’?/ She doesn’t care about anything.” While the domestic trap could be life-denying, Morrissey’s misanthropy would be mere morbidity were it not for Marr’s life-affirming musicality. Marr’s alternation of sonorous arpeggiated chiming with charging, funk-infused strumming is as convention-defying as his co-writer’s contribution, but, effected with effortless warmth, renders the track transcendent rather than truculent.

While the radio session ‘This Charming Man’ lacks the single’s high-life intro and high-pitched shrieks, this earlier version is more exuberant – sonically fuller, one of music’s greatest guitar-riffs better articulated, and with the rhythm section’s Motown bounce much higher in the mix (note Rourke’s cork-popping parps at 1:04, 2:05, 2:15 and 2:36). With the lyric beginning with deflation – the punctured bicycle, the desolate hillside, another coerced marriage – but ending with elation (“the leather runs smooth on the passenger seat”; at least the possibility of freedom), Morrissey’s misanthropy, truculence and resentment are alchemised here into humanism, transcendence and sheer delight in living. At such moments, a band conventionally regarded as morose become majestic, powered rather than flattened by “life’s complexities”, which spark the shimmering indeterminacy and teasing open-endedness that is the essence of Hatful Of Hollow.

Toby Manning’s Mixing Pop and Politics: a Marxist History of Popular Music is out now on Repeater.