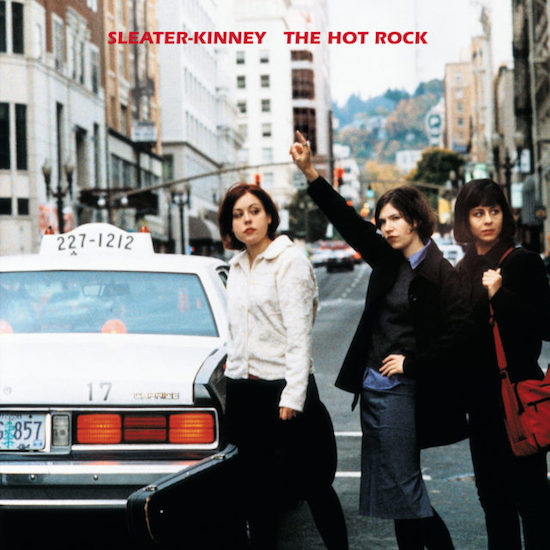

The first time I heard Sleater-Kinney I felt as if I’d been struck by a lightning bolt. The song was from the band’s newly released fourth album, The Hot Rock. ‘Burn, Don’t Freeze!’ was the tale of a passionate, claustrophobic relationship told through the duelling, overlapping vocals of singer-guitarists Carrie Brownstein and Corin Tucker.

“I’d set your heart on fire

(When you saw me, on that first day)

But arson is no way to make a love burn brighter

(Said I’d blossom under your care)”

I loved everything about the song — the adrenaline-inducing howl of Tucker’s voice spliced with Brownstein’s lower, softer vocals, the rumble of Janet Weiss’s drumming, the spiky guitar lines with no bass to anchor them. I had no frame of reference for such music. It was electrifying, it was riotous, it was incredibly sexy. I know describing music by an all-female band as sexy sounds a bit creepy now that I am a 35-year-old man, but at the time I was a sixteen year old girl and a queer wrestling with an enormous sense of shame. This was the music I needed to hear.

After that first radio encounter I bought The Hot Rock and proceeded to wear out the CD, as well as the cassette I’d taped the CD onto to listen to on my Walkman, and in the car, when my long-suffering parents would allow it. Every track spoke to me, and the emotional extremes of adolescence, like nothing else. From the anxious exhilaration of opener ‘Start Together’ to the explosive desire of ‘Get Up’ to the introspective, multi-layered brokenness of ‘Quarter To Three,’ everything I felt —and boy did I have a lot of feelings— was there in sonic form. The guitar riffs were like little jolts of electricity, the thundering drum breakdowns made my heart feel as if it were on drugs, not that I was cool enough to have taken any. At points Tucker and Brownstein’s vocals would thrillingly blur together, barely giving the listener a chance to process the intensity of the words. Flourishes throughout the album such as the use of violin (played by Seth Warren of Seattle band Red Stars Theory) on ‘Memorize Your Lines’ and on the plaintive ballad ‘The Size Of Our Love’ made The Hot Rock a record of huge atmospheric and emotional range.

Whilst the musical elements were working at a chemical level on my teenage brain, the thing I consciously focussed on were the lyrics. “There’s something so safe about a lack of air / Only way to make sure that you’ll always be there” sings Brownstein in ‘Burn, Don’t Freeze!’ I don’t know if my boundaries are better at 35 or if I’m dead inside, but I can honestly say I cannot imagine feeling like that about anyone ever again. However, throughout most of my teens and twenties that desperate longing made perfect sense. Of course, the relationship described in the song is hardly one to strive for, but it was that urgent need for connection and intimacy and spark that I related to. These were things that, up until that point, largely because of my queerness, I believed I would never attain. Of course, when I emerged from adolescence and began embarking on volatile relationships with women, the album’s lyrics were still doing a great job of reflecting my feelings back to me. “I know my heart is my worst enemy” Tucker declares on ‘Living In Exile’. The words are sung over crashing cymbals and frantic whirling guitar as if she were about to crack, trashing the potential of the lyrics to sound cliché. “There’s a part of me that works just like a child / There’s a part of me that’s you” goes the devastating climax of ‘Don’t Talk Like’.

To my ears the whole album seemed to be dripping with queer desire. It was there in the electric intensity of the vocal interaction between the vocalists. “I know not to beg” sings Brownstein on ‘Memorize Your Lines’ to be answered by Tucker’s “Will you stay here? That’s a Dirty Girl.” Lyrically I found queerness everywhere: “If you want me in your bed we’d better do it on the sly” Brownstein sings teasingly in ‘One Song For You’; and who has to do it on the sly? Queers! “Yeah I got this secret code that only flame holders know how to use,” she continues; and who has lusty secrets? Queers! “Is there splendour / I’m not ashamed / Desire shoots through me” Tucker declares in ‘Get Up’; and who needs to overcome massive societal boundaries of shame to get to their purest desires? Queers! The internet was not the thing it is now in 1998, but there were still forums for me to scour, hungry to find out if my suspicions were correct and Sleater-Kinney were in fact a band of queers. It didn’t take long to discover that two members of the band had been outed as bisexual in an article for Spin magazine some time before The Hot Rock’s release. I probably had no business knowing any of this, they hadn’t come out voluntarily, and regardless of any of the individual band members’ sexuality, I don’t think Sleater-Kinney have ever officially identified as A Queer Band. But it’s hard for me to disentangle the little I knew about their personal lives from my relationship to their music as a teenage dyke starving for representation.

This was still a few years before the abolition of Section 28 (the law bought in by Margaret Thatcher to ban the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ in schools), at a time hardly anyone was out in the media and a time before queer, trans and other marginalised groups had fully utilised the power of the internet to connect socially and politically. Whatever the factors, I could only read The Hot Rock as a queer album. My sense of connection to the world beyond my bedroom and the loneliness of being a teenage girl/queer/trans was severely limited. I was drowning in a sea of shit and hormones and the buoy I clung to was The Hot Rock.

When I was younger I used to fall asleep to The Hot Rock sometimes. I know that doesn’t sound like a glowing endorsement but I couldn’t stop listening to it and felt so comforted by this music that seemed to reach a part of me no one else could, it made me feel like I wasn’t sleeping alone. Now, I can’t imagine falling asleep to it. In fact I hadn’t played the record at all for several years before I came to write this piece. I never fell out of love with it, but the prospect of listening to such a loaded album again after years in which so much had changed for me, including undergoing yet another puberty, felt overwhelming. It did feel like a lot to process upon the first re-listen. As much as it was a joy to hear, I couldn’t put it on again immediately. I guess I’m weary of feeling All The Emotions All The Time the way I used to. I’m sure I would not be overwhelmed were this the first time I ever encountered the record, but the idea that any of us can separate the music we love from our history is farcical.

Another reason I have a hard time playing the record on repeat now is the adrenaline. The rush I get listening to The Hot Rock means I can’t be still when I hear it, even the slower songs. I have to start running around or shaking my hands or my legs start to twitch. As Tucker sings on the glorious staccato-guitar featuring, semi-spoken-word anthem, ‘Get Up’, “My soul is climbing tree trunks and swinging from every branch”. That’s literally how I feel when I hear the record, which is amazing, but not always practical in a shared house or on the city streets. I have friends who hate ‘Get Up’ for the cheesiness of its lyrics. On re-listening, I can appreciate how corny some of the lines are, but the song is so thrillingly joyful I can’t help but continue to love it. And isn’t a celebration of unabashed desire and letting go allowed to be a little corny?

One thing that made me laugh listening more recently to poignant break-up song ‘Don’t Talk Like’ was the refrain of “Don’t talk like you’re 19 / You’re 35 if you’re a day”. When I first heard those words I was sixteen, repressed, closeted and scared. Nineteen actually seemed pretty old and 35 seemed like a hundred years away. Yet the record has stayed with me over the last twenty years and become a part of my DNA. The Hot Rock set me off on the discovery of feminist punk, zines, DIY music, queer culture. So much of who I am today is a result of that record.

By some accounts The Hot Rock lost Sleater-Kinney some fans. Compared to the run-you-over-with-a-truck power punk of the first three records (which are all brilliant, by the way) The Hot Rock is considered subtle and experimental. That’s not how I’d describe it, but the band were certainly going in a new musical and lyrical direction. Sleater-Kinney gained perhaps their greatest slew of new fans when they released The Woods in 2005. The Woods is the closest Sleater-Kinney have come to making a noise album with its crunching reverb and twenty minute guitar blowouts. Suddenly all the misogynistic male journalists who’d treated the band as a joke throughout their career were onside. The Woods is a genius record and further proof of the band’s constant innovation, even at breaking point (they split up the following year and wouldn’t play together again until 2014), it just wasn’t the record that saved me. Many people now come to the band because it’s got that person from Portlandia in it. However you come to a band you love it doesn’t matter, but I’m grateful I came across Sleater-Kinney at the time I did, with the record I needed the most. It’s taken me a few weeks of cautiously going back to The Hot Rock every so often but now, everything I said before be damned, once again I’m playing it on repeat.