Sometimes our minds throw rope bridges between one art form and another. It can be difficult to fully comprehend why, but we persist with the feeling of connection, picking up clues over time. One imaginary connection that I can’t shake off is between Alain-Fournier’s magical novel from 1913, Le Grand Meaulnes and Simple Minds’ 1982 long player, New Gold Dream (81–82–83–84). Both book and record elucidate the intense longing for places, or states of mind where we feel inspired to think of the possibilities in our lives ahead. And with both, the flipside, the regret for what never came to pass, is also never far away.

Le Grand Meaulnes (The Lost Domain) narrates the adventures of Augustin ‘Le Grand’ Meaulnes, a French schoolboy who, after losing his way on an errand, chances on a faerie-like costume party in an old château called Les Sablonnières. Here he meets the girl of his dreams, Yvonne de Galais. After this adventure – and a traumatic journey back to his school – Meaulnes has only one idea: to find the mysterious château again and marry Yvonne. Except he can’t find it, or her. The Lost Domain becomes an alternative reality, played out over the years in the memories of the story’s characters. The same could be said of those who listen to New Gold Dream.

The lyrics on ‘Big Sleep’ or ‘Hunter And The Hunted’ could have been written for Meaulnes as he pores over maps in the schoolroom or paces up and down his attic bedroom in the dead of night, trying to retrace the precise whereabouts of his adventure in his head: here the gawky teenager is truly a “figure in late night plans”. Time, for Meaulnes, suddenly enters a new dimension. As in ‘Hunter And The Hunted’ it “moves so fast”, or it mutates in the fashion of ‘Big Sleep’, where his adventure “could have been years or only seconds ago”. As we note, New Gold Dream contains a great number of couplets or phrases that seem to place the listener – or the song’s protagonist – in a golden Neverland, or Prospero’s island, a place full of fairy noises, just out of reach. On the title track the listener is asked to “dream in a dream” with the band. Elsewhere we are served up multiple timeshifts, unexplained situations, or similar vagaries: unnamed hunters and hunted, figures “lost in the crowd”, people crying in the ‘beauty of both worlds” or others “slipping back on golden times” and “breathing with sweet memories”. And where is that certain “someone, somewhere in summertime”, where indeed did they go? It can be disorientating, even as the band’s chiming music continues to seduce.

Yet the album’s lead single, ‘Promised You A Miracle’, can also be seen as marking a particular time in western European popular music history, and a definite new start for Simple Minds themselves. In a charming and highly personal recent piece for the Dutch paper <a href="https://www.volkskrant.nl/cultuur-media/40-jaar-promised-you-a-miracle-hoe-simple-minds-afrekende-met-het-pessimisme-in-de-pop~baa55599/” target="out">de Volkskrant, journalist Gijsbert Kamer picks out ‘Promised You A Miracle’ as a key track that signalled an end for the then fashionable pessimism in Dutch pop music. Kamer’s premise has some international traction; 1982 saw a new and concerted alternative “smart pop” assault on the British charts in particular from the likes of Associates, Heaven 17 and Scritti Politti. As Kamer points out, these developments also took hold in the Netherlands. The doomdenker sound of Joy Division, Siouxsie Sioux, The Sound and The Cure no longer set the emotional agenda. Simple Minds’ sparkling fusion of pop, funk and a sort of muscular symbolism (the latter reaching its apogee with the last two tracks, ‘Hunter And The Hunted’ – with its gloriously raga solo by Herbie Hancock – and ‘King Is White and In The Crowd’), pointed to a mainstream music blessed with a formidable emotional and intellectual hinterland.

Kamer is right to pick out ‘Promised You A Miracle’ as a lodestar track, and guitarist Charlie Burchill was right to call it a “strange little song”, Simple Minds’ first real success and possibly their first concerted attempt at writing “proper” chart material. Despite its wistful nature, the song also has a disruptive element; the Arial to the album’s Prospero. Its funky radio-friendly presence still manages to stand out on the rarefied air of the A-side. This impish character is best heard on a couple of early live iterations, especially a gig at Gothenburg on 2 February 1982, where the band members sound as if they’re taking turns to train a playful and headstrong puppy.

If the lead single kickstarted a new, “public” time for the band, the run up to the making of the album documents a personal, inbetween time, one that presaged further change. The period between the summers of 1981 and 1982 was the moment where Simple Minds were physically regrouping and being remade into something less hermetic but equally elusive.

In Graeme Thompson’s recent biography Themes For Great Cities, keyboardist Mick McNeill asserts the departure of original drummer (and van driver) Brian McGee as being the pivotal moment in Simple Minds’ history. Previously their imposing cyber funk was the result of the rhythms bassist Derek Forbes and McGee would create in the studio. With McGee leaving, “the whole personality, the whole dynamic of everything we did changed.” Step forward – for now – former Skids, Slik and Zones man Kenny Hyslop, who started to play with the band in the summer of 1981. Hyslop, “a fabulous drummer and a pain in the arse” according to manager Bruce Findlay, defrosted some of their glacial rhythms and brought a lightness and iridescence to their sound. Certainly the bootlegs of the period, especially fantastic shows in <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DZWpbzhrdxQ&t=2s” target="out">Sydney and <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=id5LK1JZWQE&t=0s” target="out">Glasgow in December 1981, reveal a pulsating beat boasting spacier elements that in turn allow previously sunken melodies to bubble to the surface. Then there is the story of other band members picking up on Hyslop’s constant playing of a tape from a New York radio show mix, featuring the track ‘Too Through’ by Bad Girls. That song’s riff sparked off a series of sonic mutations that formed the inspiration for ‘Promised You A Miracle’: a demo given definitive shape by another key figure who enters stage left, the album’s young producer, Peter Walsh.

Hyslop’s idiosyncratic personality eventually proved too much for a band with a strong collective sense. Three drummers contributed to the final release; Mike Ogletree adds mystery to ‘Colours Fly and Catherine Wheel’, Hyslop lays down the squelching beat to ‘Promised You A Miracle’ and future mainstay Mel Gaynor brings considerable presence and a steady thump to the rest. Gaynor and Ogletree combine forces to drive the totemic title track.

Other creative mutations in late 1981 and early 1982 point to a band and their ambitious label, Virgin, looking to assess what had gone before; either to build something new from half-realised ideas or to park old sounds and attitudes for good. There are sonic portents on their previous long player, Sons And Fascination / Sister Feelings Call that find their way onto New Gold Dream, especially the gloriously melancholic side two of Sons And Fascination. It is interesting that the band released a prettified instrumental version of ‘Seeing Out The Angel’ as the B-side to the ‘Promised You A Miracle’ 12 inch (the sparkling, wistful interplay between the guitar and keys is more akin to a Michael Rother solo release). Thinking about alternative futures and unreachable pasts also took shape on an Australian tour in December 1981, where Simple Minds first experienced tangible chart success. The adrenaline surge of the pop world, and the band’s increasing canniness in playing to its whims alternated with the band experiencing the sort of catatonia engendered by days on the road. The latter experience led to Kerr entering a personal, Glaswegian take on The Dreaming. “I was looking at the sky and it was like seeing the sky for the first time”. The sight of petrified forests made Kerr “think about the world as an old place”. This mix of melancholy for all that has gone before with a boundless sense of optimism in being alive is a key theme in the music found on New Gold Dream. Less elegiac musings on futures and pasts can be seen with some promotional actions by Virgin. Early copies of Sons And Fascination had a “Simple Minds Information Sheet” pressed inside them (upsetting the 13th Floor Elevators-style mystery of the golden inside sleeve, with its white cross). Then there is the Virgin compilation LP, Celebration, released a week or so before ‘Promised You A Miracle’ in early February 1982, seemingly cashing in on the previously unreleased 1979 track, ‘Kaleidoscope’. This record feels – by virtue of its slightly drab artwork – to be from another era entirely.

But when thinking about the power and allure of New Gold Dream as a whole, these kinds of facts are just the driftwood on memory’s beach. Like Meaulnes’ search for the enchanted château, and maybe led off the scent by the caressing opening riff of ‘Someone, Somewhere In Summertime’, creating a definitive narrative around the album’s elusive magic never takes a straight course. The work compiling this piece has been prey to constant distractions; including searches for old quotes from the band squirrelled away in old notebooks or underlined in yellowing cuttings, or revisiting neglected bookmarked webpages that have since been erased as digital records. I have spent hours trying to make half-thoughts or memory traces tangible whilst rummaging through old tapes that have lain unplayed for years. Sniffing out significant aural gestures or moments in this way has been an exercise in hauntology; these moulding bootlegs offering up yards of muffled gloop, gurgling passages of stretched tape or clouds of hiss, the music sometimes swamped by chatter or other ambiences and actions. Still: these tapes – especially the shows of late 1982 – reveal a band that knows it’s in a magical place. It can be heard in the reworking of their earlier work, the machine press thuds of ‘The American’ and ‘Sweat In Bullet’ becoming stretched and funky, playful and cavalier. It can also be heard in the way Jim Kerr adlibs and emotes throughout the tour: we note that “Life goes…. So fucking fast!” on ‘Hunter And The Hunted’ at the Leicester de Montfort Hall show, as if Kerr senses but can’t fully comprehend the sheer power of the whole. These things are sometimes uncool for sure, but the band speak in tongues and takes their audience with them, oblivious to everything but capturing that moment.

These tapes also reveal the Baroque majesty of album tracks like ‘Colours Fly And Catherine Wheel’ and the album’s second single, ‘Glittering Prize’. ‘Colours Fly and Catherine Wheel’ is a glorious track both on record and live; the song – courtesy of the arpeggios wrung out of Burchill’s guitar – a mercurial, quicksilver presence that flits through the space like the half-mythic figures in Boticelli’s Primavera. According to previous biographer Adam Sweeting, the band didn’t like ‘Glittering Prize’, but on gigs like the December 1982 shows in Glasgow and Sydney, the track has found a pace that allows its regal gestures to shine through. Other evidence, things we can see and project upon in a different way, add further mystery. Watching what can be documented, such as The Tube sessions in Newcastle upon Tyne in late 1982 (shot prior to a gig that proffered up a powerful take of ‘Hunter and the Hunted’ for the B-side to 1983’s ‘Waterfront’ single), we can note how the band moved at this period; a sensual, sinuous anti-dance that also doubles as a sort of weird Pierrot act. Completists can also watch the circumspect but polite Jim Kerr and Charlie Burchill fending off questions with earnest dreamspeak and shy rebuttals in that show’s interview. Yet more material that can be lined up in any way you wish. In short, the things that don’t really need saying here. Maybe we should mirror Augustin Meaulnes, writing a dejected letter to the novel’s narrator, bewailing the length and ultimate futility of his search for Yvonne: “It is best to forget it all”.

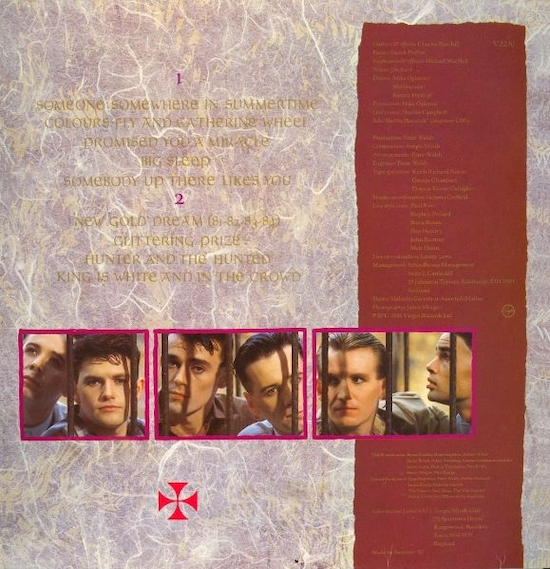

Still: when turning to the album proper it’s impossible to deny the sense of quiet majesty it offers, even when thinking about it, or looking at the spectacular cover. Third eyes are opened with artwork that really does manage to “dream in the dream” with us. Similar colour-driven prompts are evoked in Alain-Fournier’s novel; such as the yellow sparks of molten metal set against the dark umber of the wheelwright’s on the night before Meaulnes’ mad escapade. We can also point to the sultry greens of the undergrowth at the old boys’ riverside picnic, or the contrast of the sky’s burning bright blues and crystalline white of the hoar frost as Meaulnes rides through an utterly deserted rural landscape. These things don’t need a rereading of the text to remember them. The cover of New Gold Dream, with its rich golds, plums and burnt oranges acutely reflects a sense of being in another place, or in one’s own inner world. Its perfect partner is the lovely, coy instrumental that closes the A-side, ‘Somebody Up There Likes You’, an elfin piece that almost shimmers in the mind’s eye.

One last thing to note: the sheer glory of the title track. Sitting expectant like an unsprung trap on side two, ‘New Gold Dream’ powers off into the ozone courtesy of a two-drummer thumping beat and a magisterial synth part that channels Handel and Harmonia all at once. Somehow, despite the deeper register of his voice, Kerr manages to avoid sounding pompous and rides the music, allowing Burchill’s transcendent guitar line to bubble up and send the song into another stratosphere. Full of hope and power, this is possibly the band’s greatest moment.

The road to hell is paved with good intentions. Meaulnes, initially the undisputed boss of the schoolyard, sees his social power unravel after his visit to Les Sablonnières. He spends years in a fruitless, often strange search for Yvonne, the colours of his dream sometimes turning a nauseous, spectral hue. Ultimately he finds a quietus of sorts, despite some shattering developments. Simple Minds are also shaken by the aftermath of their dream –success and expectation demand their internal sense of self and manner of playing pop music’s game undergo drastic change. <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yI7Qbzss4fE” target="out"> Hanging out with U2 at festivals like Werchter 1983, the band dropped the makeup and hair dye and went for the jugular on stage, playing to increasingly jubilant and maybe less bewitched audiences. It’s sad to say but 1984’s Sparkle In The Rain still feels like a bit of a dog’s dinner, maybe for not wanting to be New Gold Dream; the increase in noise and bombast seemingly needed to flush the potency of their previous album out of the band’s internal organs. The odd slight return in these later years, such as the beautiful instrumental ‘A Brass Band In African Chimes’ only serve as a memory lapse after waking. Too late: the hands of fate, in the shape of The Breakfast Club soundtrack and Bob Clearmountain and Jimmy Iovine, saw them become part of – however bemusedly – the high gloss soundtrack of the mid-to-late 1980s. But we still have New Gold Dream.