In 1989 a peculiar debut album was released, its songs explicitly crafted around the matching of two female voices, high and low. The soprano, Marcella Detroit, sang in an extravagant falsetto designed to contrast with the dead-flat intonation of Siobhan Fahey. Lyrically, one might guess that Detroit would play angel to Fahey’s devil, and this is sometimes the case: with her harsh ungiving voice, Fahey can sound like a sadist, torturing Detroit into exquisite fluttery cries. On the track ‘Twist the Knife’, Detroit’s vocal exists largely to let us know that "it hurts"; throughout the album she releases wails and "ows", both pained and ecstatic.

Part of the pleasure of Shakespears Sister is listening to the shifting interaction between these two: playing Jekyll and Hyde, good cop versus bad, or coming together to defeat a common enemy. Sacred Heart sees the women taking on a parade of distinct characters. Depending on the context, they might evoke a princess and her captor (even if Detroit’s voice is way too high and histrionic for a romantic lead), a pair of gorgon sisters, or the Fates (we get the feeling that Detroit could be appeased, but Fahey remains pitiless). Most strikingly, all the voices on this album have a powerful sexuality which is specifically linked to aging. Witch, maternal lover, vamp on her deathbed: these are roles which combine allure with decay and disgust. In today’s pop landscape, age is a much bigger taboo than sex – therefore an album which thoroughly combines the two subjects is wondrous to hear.

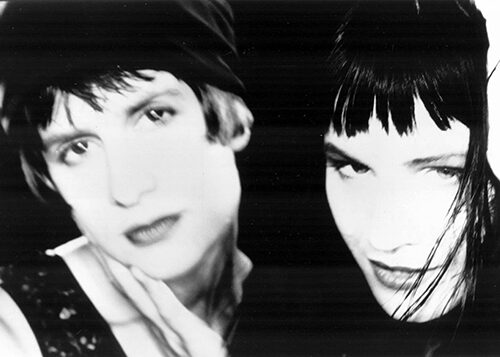

The consensus on Shakespears Sister‘s origins is that former Bananarama singer Fahey – then known as a luscious golden blonde – lowered her voice, plastered her face white and wrote scathing lyrics, finding acclaim in the process. But despite these contrivances, this is a band of genuine idiosyncrasy, prepared to discomfit us on the deepest levels. Fahey’s persona goes beyond goth into grotesque: even when her voice is dried and cracked, it continues to insinuate sex. In videos and performances, she is both lecherous and dead-eyed. It’s a combination which traditionally inspires repulsion – and hasn’t been seen again until the remarkable Azealia Banks – but in Shakespears Sister, sex tends to be accompanied by an image of horror.

The opening track, ‘Heroine’, is the key to establishing this blend of lust and impersonality. Fahey’s protagonist fantasizes about rescuing her man from death, and invents various scenarios where this might happen: a freezing winter at midnight, a last-minute phone call and knock at the door. But something is off: why the insistence on these exact conditions, which are repeated over and over? Why does she keep saying "Oh, baby" in that tone, which sounds excited rather than fearful? Fahey offers her lover protection and sacrifice, but only on very specific terms. Between the "dead of night" and the "blue, blue flowers", everything must be visually right, and one wonders if the singer has betrayed her man in order to have the satisfaction of saving him. Women may dream of rescuing and being rescued, but this damsel has darker intentions than the male: she is closer to a Nick Cave-style murderer than a romantic maiden.

Fahey’s vocal here is like a drill to the head. While her character appears to offer nurturing warmth and comfort, her delivery is flat as a tack: each syllable is studded in tight, as if through gritted teeth. When vows of love are recited in a cold, robotic voice, the situation seems not only unreal but forced. Fahey huffs like a sergeant, and the song is punctuated with other sharp sounds: a metronomic beat and a vibrato note from Detroit, which when sampled suggests emotion on tap. This is a ghastly version of romance, in which every gesture is pre-programmed and the scenery comes as part of the package.

In general, Detroit’s vocals, with their over-the-top flounces, show up the disdain of the Fahey voice, which has no juice or looseness at all. A song called ‘You Made Me Come To This’ implies a sexual tribute, but Fahey turns the title phrase into a curse. In ‘Heaven Is In Your Arms’, the refrain of "I will never leave you" sounds more like a threat than an oath, dripping both honey and irony. When desire is expressed, it tends to be of the Joan Crawford kind, the love of a creepy mother figure.

One of the most arresting tracks on the album, ‘Electric Moon’, is equal parts passion and detachment. It presents neon imagery against a black landscape, which tends to be the colour scheme for Shakespears Sister, as in ‘Heroine’, ‘Red Rocket’ and ‘Dirty Mind.’ As the song starts, a male grunt ("huh") sets the rhythm, and Fahey begins an unusually delicate vocal, playing a tender-hearted lover who gets sentimental at night. But in this quiet atmosphere, it is the ready-made sounds which stand out: the "huh" noise, the bright click-clack beats, and Detroit’s trill, which sounds like a synthesizer effect. Although the grunt communicates a specific feel – an urgency which has been dulled – it seems as if all the emotions here have been sampled and automated, including Detroit’s aroused quiver, which provides pain on demand. Even Fahey’s nostalgia ("that old moon’s got me in its spell") is curiously rote and generic. Although this is ostensibly a spiritual number, our overwhelming impression is of stark, synthetic sounds against blankness. The last noises we hear are the masculine "huh" and the click-clack, which conduct their own mechanical romance as the song fades out.

In an even more impersonal vein, ‘Red Rocket’ anticipates the sci-fi tone of the band’s second album, Hormonally Yours (1992). This time Fahey takes on the role of grunting timekeeper, but she doesn’t sound too thrilled about going to the moon; her "wow" (no exclamation mark) is precision-honed and joyless. This isn’t the zany posturing of Janelle Monae, for whom space travel acts as more of a style and fashion element. For Fahey, sci-fi is never an escape from overwhelming ennui. Although there is no shortage of musical inventiveness on the album, this and several other tracks end by repeating chorus to fade, which only enhances the feeling of soulless iteration.

Perhaps the most difficult track to listen to is ‘Primitive Love’, a cavewoman rant about not caring. This song, in which a woman knowingly picks up a bonehead, is excruciating – for good reason. We open with a thick ugly bass – the most flatulent bassline ever recorded – and then a series of harsh beats which evoke a cheap setting, possibly a hen night at a strip club. There are wolf-calls and whistles, noises which are comically tinny against the blast of the bass. Clearly this song, on which Fahey has sole writer’s credit, is designed to repel on a gut level. What turns out to be monstrous, though, is the main character, who has big blunt desires and an outsize lust. The loud, tramping beats suggest bones rattling and gorillas dancing: a woman who is truly panting and primitive in her search for a lunk to "get me out of this trance." There is no verse to explain the back-story for this, as Fahey just keeps repeating her mission statement ("Ah ha ha, I need a primitive love, yeah"). Female artists rarely release songs this squalid, yet this track plays with our ideas of what constitutes sleaze and filth. Do we recoil from the directness of its message, as much as we do from the ear-splitting sounds of the bass?

Elsewhere, Fahey challenges our notions of love by drawing on a trope of old Hollywood. One of her persistent themes is the idea of a woman with a long romantic history redeemed by contact with a young lover, who offers fresh hopes and idealism. It is the paradigm of "man with a future, woman with a past" that we sometimes encounter in 30s cinema, but very rarely in music these days. This is the kind of fable where a witch grows young in the arms of a knight, or an aging diva meets a pure romantic lead – she is more Garbo than Gloria Swanson, since her situation is tragic and affecting. In ‘Heaven Is In Your Arms’, this character walks through the gallery of her past and re-encounters one of her favourite conquests: the one that got away, who haunts her with his sweetness. On ‘Sacred Heart’, the praise for the lover is even more over-the-top, so that the listener is placed in the position of this idealised but impersonal beloved. Fahey refers to herself as a "fallen angel", a brittle woman with a soft spot for just one guy. As in Mae West’s films, men are the figures of sensibility here: they provide youth, integrity, physical strength, ardour and innocence.

The narratives of these two songs merge with a third, the single ‘Run Silent, Run Deep’, which is both epic and melodramatic. Fahey’s voice is tough and leathery but suave, as she looks back on her life with the resigned air of a Marlene Dietrich. The descriptions of her love interest ("You’re soft and naked/You’re young and strong") imply that she is none of these things: she is cynical, worldly, and given the goth and military references, probably clad in black leather, as Dietrich was for her execution scene in Dishonored (1931). The man she describes is a lover/assassin whose vigour is both a threat and a turn-on, and fear and desire become increasingly confused. We never know whether she is aroused by her own killer or the prospect of death in general.

In ‘Heaven is in Your Arms’, this mood of disorientation is created by the blurred bell sounds, echo effects and the long trailing guitar lines which suggest a hark back to earlier days. When Fahey’s character becomes confused about who she is talking to ("Or was I just imagining things? It seemed so real/ Something that you left behind"), she might be remembering any of the male figures in ‘Run Silent, Run Deep’, ‘Sacred Heart’, or even ‘Heroine’: they all coalesce into the same type, visually and emotionally. The entire album is a closed world, caught in a spiral of recurring thoughts and imagery.

In the 70s and 80s, pop songs were often sung from the point of view of an experienced courtesan, a Camille-like figure epitomised by Stevie Nicks, Johnette Napolitano, Randy Crawford, and often Debbie Harry. This was also the era of the "empathetic" prostitution song, in which Crawford or Tina Turner might invite us to share the struggles of a private dancer. The protagonists of these songs were both ravaged and romantic: wised-up, sated with sex, and with the kind of jaded glamour a teenager might envy. Now the wizened voice of experience has vanished from the music scene, at least as far as female stars are concerned: today’s pop singers may be "fierce", but any hint of age or weariness is eliminated from the image.

On Sacred Heart and Hormonally Yours, Shakespears Sister go even further than the singers of past decades. Fahey creates a more convincing picture of glamour gone to seed than, say, Courtney Love, and fills it out with a startling level of narrative detail. Fahey plays the part of the ruined ex-beauty queen, but takes it into the bizarre and unpalatable. In ‘Run Silent, Run Deep’, she depicts herself as death warmed up by a young lover. ‘Primitive Love’ is sung by a grown woman who is all but foaming at the mouth, with a candid sexual greed not seen since Barbara Stanwyck in her 30s Warners films. Given the current obsession with defining "classy" standards of female behaviour, this model of crude, unevolved sexuality remains inspiring.

Above all, there is the uncertainty over Detroit’s status in relation to Fahey. Is she an echo, an antagonist, or an alter ego? Do her shrieks tell Fahey she’s gone too far, or are they a parody of girlish helplessness? The power dynamic between the two keeps changing, and tracking their relationship turns into a game of bait-and-switch. Through their multiple personae, Shakespears Sister launched a series of extreme archetypes: the cold-eyed woman looking for a pick-up, the crone grown perversely sexy in her dotage, the devoted heroine who might also be the villain. And they were able to parlay these roles into mainstream success in the 90s, without being mocked! That in itself is worth marvelling at.