“For half a century they hated each other and we loved them for it.”

Siobhan and Marcella. Marcella and Siobhan. The order matters. The order is critical. Siobhan came first and Marcella arrived next. But who came first in the public mind is another matter, and the heart of the conflict. It all started as Siobhan’s party – a ‘Singles Party’, in the pointed title of a song from #3 (2004), the third Shakespears Sister album and the first to feature, as Siobhan Fahey had originally intended, a line-up consisting of Siobhan Fahey.

The debut LP, Sacred Heart (1989), had begun as Fahey’s solo project, with Marcella Detroit as a hired gun. It was Fahey’s then husband, Dave Stewart (a.k.a. Him Out Of Eurythmics, of which more anon, because it plays a notable part in this tale), who persuaded Fahey she would be better served by making Shakespears Sister a duo. He was absolutely right, and very wrong. Artistic triumph. Personal disaster. You know – the story of almost every great band ever.

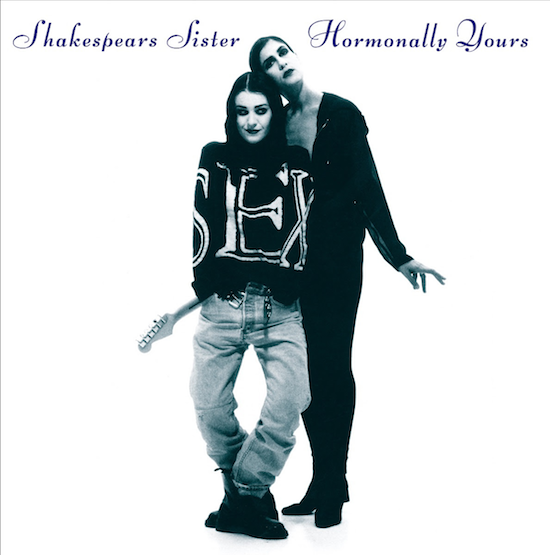

In between, then, came Hormonally Yours (1992), the 30th-anniversary edition of which is the present object of our contemplation. There are, officially, four studio albums by Shakespears Sister, and all the others have things of merit on them. But this is The One. It’s also, and not coincidentally, the only one (thus far) conceived and recorded by the pair as equals – bristling, uneasy equals, even then, crucially so – and the one on which their reputation rests. As well it might; that’s like resting upon a giant, ornately hand-carved mahogany four-poster bed with a goose-feather mattress and black silk sheets skirted in lace. It’ll do.

Thirty years is not half a century, as keen observers will have spotted. The “half a century” line was borrowed by Fahey and Detroit from the television series Feud: Bette And Joan to introduce their reunion shows in 2019. But what’s a couple of decades either way between frenemies?

The first thing that will flit across the transom of almost any pulp-literate person when reminded of Bette Davis and Joan Crawford is What Ever Happened To Baby Jane?, the gloriously overblown 1962 cult flick in which the pair at once leveraged, spoofed and acted out their notorious vendetta. Sound familiar? It must, surely, have been the inspiration, the key text, for Hormonally Yours, if not for the whole fractious alliance. Well, no. It turns out the initial spur for the album was a different film, a bargain-bin 1953 B movie bearing the most bargain-bin 1953 B movie title there ever has been or ever could be, Cat Women Of The Moon. Instead of doing that soundtrack-to-an-imaginary-film thing, Shakespears Sister started with the premise of an alternative soundtrack to a real film – which, as the original score is by Elmer Bernstein (slumming in Hollywood’s back alleys after being blacklisted for his refusal to name names to the House Un-American Activities Committee), was quite an audacious proposition. But that was the point. “They were bold,” Detroit has said of the titular Cat Women, “they were daring, unapologetic about who they were.” They were also, distinctly and definitively, Not Nice – least of all to any virtuous simp of an Earth girl who stood between them and their wicked designs and passions. No sisterhood there, sister.

Even before “Girl Power” became a slogan, there was a tacit convention that all-female groups must be more Sister Sledge than The Supremes. Whatever their internal dynamic, they should present a united front, us against the world. There are books to be written on why this might be so. It’s certainly understandable. In a world designed (as Caroline Criado–Perez’s Invisible Women documents, this is neither an overstatement nor a misapplication of that word) to diminish or exclude women, such a front must feel essential. But it’s not necessarily the truth.

Shakespears Sister put a spiked heel through that convention and theatrically dropped it into the bin. It’s not that they weren’t explicitly feminist: the name itself was drawn from A Room of One’s Own, Virgina Woolf’s essay about the cultural space denied to womankind. Rather, that among the rights of women must be included the right not to be able to stand one another.

Here was a formidable sisterhood of another kind; a duo whose entire shtick was witchery and bitchery, us against each other. They were their own drag impersonators, wickedly histrionic. Fahey, the bubblegum Siouxsie Sioux (and that is intended as no small compliment), the literal young punk who co-founded then departed the premier UK girl group of the 1980s, Bananarama. Detroit, the onetime Marcy Levy, musical savant, rootsy sidewoman to Eric Clapton, reinvented as a severe, sombre variation on a 1920s star of expressionist cinema. One of those perfectly imperfect yin-and-yang pairings each component of which filled the space the other could not, generating endless tension and friction along the border where they rubbed together.

How much of this was mere shtick, a kind of French-and-Saunders act by other means, and how much sincere antipathy? One doubts even they know, any more. Nor does it matter. What matters is the way it all knitted together to produce the kind of album that isn’t only a tremendous record, although it’s certainly that, but the unimprovable expression of a sensibility, an idea, a moment. The kind where everything meshes beautifully. Fahey’s art-rock predilections (Bowie and Roxy Music were at a low ebb of fashionability just then, remember) and her Dietrich/Nico growl – a mordant contralto confected from tarpaulin and treacle, around which darted the coloratura soprano of Detroit, who was steeped in soul, R&B and blues-rock. The presence of Alan Moulder, eminence noire of the sleek, dark, crunchy indie sound of the early Nineties, in the co-producer’s chair. The aiding and abetting from Stewart, a pseudonymous co-writer on four of the tracks, whose 1987 joint masterpiece with Annie Lennox, Savage, and the accompanying videos directed by the marvellous Sophie Muller (soon to take up the same role for Shakespeares Sister, with equally dazzling results), provided a foretaste of an aesthetic the newer group would make fully their own.

If anyone chooses to interpret this as “Mind you, there was really a bloke behind it all”, I cordially invite them to fuck right off. It’s simply that Eurythmics, and Stewart in particular, were in the right place at the right time to light a path for Shakespears Sister and offer some assistance in navigating it. Which is how pop happens.

The songs, then. My, what songs. Arch and delectable. Poisoned acid drops, goth-pop jewels, black costume pearls. It opens with ‘Goodbye Cruel World’, a briskly paced, steady-as-she-goes pysch-pop toe-tapper that might have ornamented Prince’s Around The World In A Day, and it closes with the eerie, end times melancholy of ‘Hello (Turn Your Radio On)’, which jostles right at the pinnacle of the extensive genre of Great David Bowie Songs David Bowie Never Made. In between, there’s a run of corking tunes that encompasses far greater variety than memory might tell you. ‘I Don’t Care’, whose jaunty malevolence only The Cure in peak vaudevillian mode could rival. A first, appetite-whetting tang of soul on ‘My 16th Apology’ (which depicts all too accurately the passive-aggressive dynamic of a culprit who says sorry as often as they repeat the crime, then is indignant to find they haven’t been forgiven) – soon to be followed by the faintly Weller-ish Northern soul revivalism of ‘Emotional Thing’. There’s what amounts to a nine-minute baggy suite on ‘Black Sky’ and ‘The Trouble With Andre’, songs whose acerbic zest cuts through the wah-wah and the looped beats and the blurry, post-impressionist daubs of guitar in a way that seldom occurred within the genre proper. Then along comes ‘Catwoman’, and while it may be going it a bit to claim it accidentally invented Goldfrapp before the fact (and anyway, everyone knows Noosha Fox did that in 1976), let’s just go ahead and say it accidentally invented Goldfrapp before the fact. Every one of these ventures, even those which might in lesser hands have had the whiff of pastiche about them, is defined by the power of pair’s composite personality: Fahey’s ombré vision and mordant, irrepressible sense of mischief; Detroit’s elegant agility and taunting, elusive counterpoints.

Then, smack in the middle of it all, the iceberg into which their musical union sailed at full steam and upon which it duly foundered. Between its 9,723-week run at the top of the charts, at a time when that made a song nationally unignorable and inescapable, Detroit’s inadvertent thunder-stealing (it’s the only song on the album that places her solo vocal front and centre, but the casual listener would have taken her to be the frontwoman), and that sketch by The Mary Whitehouse Experience, which has dogged it forever after, ‘Stay’ proved effectively unsurvivable. It was a wish granted on a monkey’s paw, a massive, career-rocketing, life-changing hit that lifted and ruined everything. Yet in the context of Hormonally Yours, it’s exactly what it should be, exactly where it should be. This isn’t a concept album, per se, but it’s conceptually cohesive, and ‘Stay’ fits into it just so. It’s difficult to overstate how much better it works there than as an individual piece, and how much better it represents the band.

Tagged onto the end of this anniversary edition is a trio of demos that didn’t make the cut first time around, two of which have recently appeared on compilations: ‘Cat Worship’, a mood piece that again echoes Bowie – think ‘Future Legend’ crossed with a Low instumental – and ‘Out To Groove’, a pop-rock number with a Go-Go’s flavour. The last bears the apt title ‘The End’, and delivers a genuinely funny impromptu pay-off. These are nice things to have, and at a guess, it was more their alignment to the discarded soundtrack idea than a lack of quality that saw them left out. Ideally, at least in physical formats, they would occupy a separate disc or tape, so as not to disrupt the flawless sequencing and perfect ending of an album that captured a remarkable creative partnership at its zenith and which, 30 years on, deserves to be heard anew and cherished.

Hormonally Yours 30th Anniversary Edition is out on August 19