The extraordinary trajectory of Scott Walker’s life and work tends to give rise to various grand narratives and myths. Yet its heterogeneity and complexity means that any one reading of his work and any particular narrative about his life collapses in the face of another. We’re often told, for example, that he’s reclusive and wilfully obscurantist. Upon the release of probably his most difficult album, Bish Bosch, he did a number of high profile interviews clearly informed by a desire to communicate his work to as large an audience as possible. While guarded about his private life, his lengthy, candid and good-humoured discussion of his career in a Thirtieth Century Man hardly exemplifies the behaviour of a recluse.

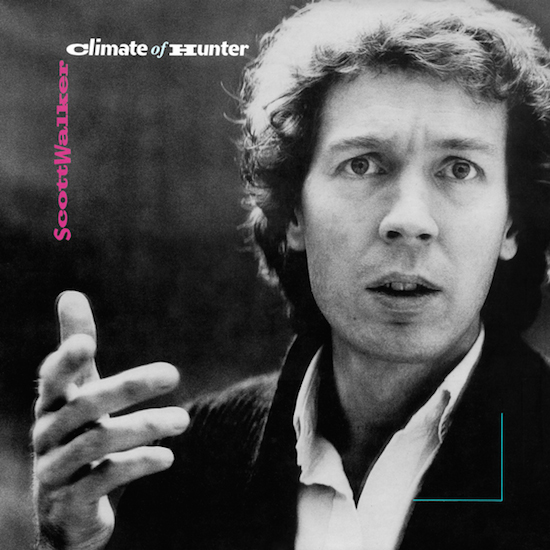

On a stylistic level, Climate Of Hunter distils many of Walker’s contradictions and occupies a relatively singular place in his back catalogue. This is the album often viewed as his comeback after years in the wilderness. After the commercial failure of Scott 4, he remained productive but ended up putting out a series of MOR flops which he’s since disowned, reverting to covers and abandoning songwriting for most of the 70s. With Climate then, he has implied he was taking up where he left off with Scott 4.

Writing in the highly recommendable No Regrets: Writings On Scott Walker, Damon Krukowski described the singer’s work from Climate onwards as an exemplification of Edward Said’s description of ‘late style’, with an increasing sense of exile and apartness and a resistance of harmony and resolution in favour of difficulty and contradiction. There’s a good deal of accuracy in this reading of some of his later work, but it has given rise to a dubious narrative about the trajectory from MOR to avant-garde.

The abstract expressionism and uncompromising stylistic difficulty of his later work certainly makes for challenging listening. Even the ambient minimalism of parts of Climate can sometimes seem like a world away from the rich baroque pop of the 60s Phillips records, but there’s a problem in over-emphasising his break in style, in that it can downplay the complexity and affective intensity of his earlier work. His career-long consistency might be a reminder that complexity, difficulty and antagonistic weirdness are not the reserve of art music’s innovatory breakdown of form, but can also be found within the constraints of the traditional pop song. Unpicking some aspects of this narrative in relation to the MOR records in the No Regrets essay collection, Ian Penman put it best: the middle of the road can be a dangerous place to be.

Moreover, the oscillations between violent silences and punishing percussion in his more recent records are a world away again from the ambient atmospherics in Climate Of Hunter. One constant over the years has been a lyrical preoccupation with isolation and exile. "In the time of an exile/ from the jails of another" he sings on ‘Sleepwalkers Woman’. More than the layers of geographic and cultural exile evident throughout his work, it is a sense of exile from the human race which has been a more consistently unsettling preoccupation. He takes us to a world where we’re reduced to "splintering bone ashes", a world where "there are no voices here/ there are only confessions". To contrast similar sentiments on ‘Jesse’ from The Drift, there is a section in which accompaniment is abruptly cut with him wailing a capella: "I’m the last man alive." The latter expression of human extinction and isolation is totally consonant with the form and delivery. With ‘Sleepwalkers Woman’ though, and much of Climate, there is a weird ambivalence: the strings are typically occupying an ambiguous space on the fringes of dissonance and a seemingly imminent resolution which never quite arrives, but with vaguely hopeful chord changes oddly jarring with the unremittingly bleak lyrical vision. Part of this record’s strangeness is in the arrangements, which are at times reminiscent of the ominous dread of Ligeti, at times fleetingly sentimental, almost Disney-esque.

Scott Walker’s vocals on this record are also quite unique. "You sing like a stranger", he says on the stand-out art-pop gem ‘Track Three’, as if gesturing towards the vocal hollowing out of personality and stripping away any semblance of sentimentality characterising his delivery on more recent albums. Yet here his vocals at times still brim with personality, even a confident, if pained, swagger, probably accentuated by a harmony from Billy Ocean.

Other guest musicians included free-jazz sax player Evan Parker and Mark Knopfler on axe-wielding duties. In Thirtieth Century Man, Parker related Walker’s insistence that, "This is not a funk session" wishing to avoid any ‘groove’ or swinging together, though the fretless bass lines throughout the album and guitar solos offer unexpected moments of smoothness.

Both the creative process and result for Walker suggest persistent struggle. He never writes of his own volition except when under contract. In 1978 he penned his first original material in eight years for the final Walker Brothers album, Nite Flights, in a mutually influential relationship with David Bowie that now became evident. He reputedly brought Bowie’s just released Heroes to the studio as a reference point, while Brian Eno similarly recounted being blown away by Nite Flights just before recording Bowie’s Lodger. This seemed like the beginning of a comeback of sorts for Walker, but then six years of total silence followed before he finally brought out Climate. He’d met Eno in the interim but didn’t want to make a record with him, as he explained, "I thought rather than destroying his career too I had to do one on my own." Interviewing him for the NME upon the release of Climate, Richard Cook asked what Walker had been doing all that time. The responses were playfully elusive: watching people play darts, sitting "in a trance", "drinking!"

Less playfully, Walker has spoken of working towards a silence from which the creative process can emerge. That creative space was actually more quickly arrived at, and a more self-confined one, than subsequent records. He finally called his own bluff in the summer of 1984 by promising Virgin he’d be ready to do a record in two months, the entirety of which he wrote in a cottage near Tunbridge Wells.

"This is how you disappear/ Out between midnight" he sings, opening the record with lines we can’t help but read biographically. Expressionist lyrics strike the listener, leaving what one thinks will be a lasting impression, but then ambiguously dissolve with the dissonant disconnect of subsequent lines which provide no narrative thread for the listener. Everything is "losing its shape /as the heat in your hands/ carve the muscle away". Thematically resonant with later work, another recurring lyrical concern is the chiselling away of what it is to be human, particularly in the form of our uncomfortable proximity to the animal kingdom. Human disintegration goes hand in hand with inhuman beastliness throughout these songs, where human characters form herds, graze like sheep, become generally indistinguishable from hunters and hunted, and are shaking to "wash the murder away".

Again this lyrical breakdown of, well, just about everything, sits at odds with the music and the delivery. There is arguably nothing experimental about Walker’s music. He knows in advance what he wants and pursues it with uncompromising intensity. The breakdown of form and meaning in the lyrics is a counterpoint to the wrought, tense and formally rigorous, if highly unconventional, musical vision.

You get the impression that Walker’s creativity is fuelled by pure negativity: a rejection of everything he is, and every identity handed to him almost from the beginning, finding inspiration instead in modernism and rejecting his American roots for Europe. Another strange thing about this record, often seen as inaugurating a radical shift in his style, is that it closes with a song that contradictorily exemplifies everything which he’s seen as leaving behind. ‘Blanket Roll Blues’ is the only non-original tune, an interpretation of a poem by Tennessee Williams. The art-pop ambience and expressionism of much of the album comes to an abrupt halt with a return to tradition in the form of a blues finale. Again though, lyrical content which deals with the rejection of society and the utter isolation of what it is to be human is delivered in humane and affectingly beautiful tones. If there’s one consistent on this odd record, it’s that it offers a compellingly humanist evocation of an anti-humanist world.

Climate Of Hunter was generally critically well received. Chris Bohn in the NME said that each song "registers shock and subsequent calm at the point of imminent death, a last minute reprieve giving him time to record just one more" while the album as a whole "invites the listener to scream in the face of destiny". Such critical enthusiasm was not matched by sales however. A follow-up was planned with Eno and Lanois but initial sessions were quickly aborted (Walker on Lanois: "I just couldn’t get along with that guy"). He was dropped from Virgin and it would be eleven years from Climate until his next album Tilt, leaving plenty of time for the myth of Scott Walker to take on a life of its own.