If I am asked to write about a record, even one I have lived with and loved, it is usually necessary to go away and listen to it, no matter how much of it already belongs to my unconscious. Rum, Sodomy & The Lash renders that an extraneous precaution. I can hear it whenever I want without having to put it on, in sequence and down to the exact track order with gaps between songs, each one a gift of the past, powered by the fumes of (my) history. I first encountered it when I was 11 (my parents drew a line at my going to the gigs) and I am now 50. With a complete lack of originality, usually on a Sunday after several drinks, I play the album again to deepen my relationship with what I already know and top up my musical muscle memory, lest it affix itself to another record my heart first opened to, and challenge RS&L’s worn and ancient sovereignty.

The school of received wisdom has it that RS&L, and The Pogues as an idea, were a luddite reaction to the synthetic 80s, and an earthy rejection of that decade’s shiny suited artifice and soulless obsession with garish novelty and unnatural materials. As with most of these superficial summations that break time into pithy cultural compounds, this idea isn’t wholly wrong, though the lived reality of the period was far richer than this reduction would suggest. Part of The Pogues’ audience, at a loss after the punk wars, certainly drawn to the group precisely because they were not Bucks Fizz, were led by a singer that not only eschewed eye-liner but dental care, and clearly did not give a damn about Fame (the cinematic musical, noun and reality).

However there was another 80s in which a thousand flowers bloomed, a time of extraordinary cultural febrility that was treated as normal by those of us who never knew worse, where musical originality was taken for granted and entire genres, dissimilar yet driven by the same hunger to go further, developed in parallel, often bumping into one another in the dark. Over-produced pop, some of which was excellent, was ubiquitous and dominated the charts, which given their centrality to cultural life meant a great deal more then than it would today. But these totems of conformity existed atop a myriad of tribal subcultures, most of which sent their emissaries into the charts too. For wannabe connoisseurs too young to rule anything out, the sounds we loved cut across the cream of every genre (which is why I still find it so hard to describe what kind of music I like). I bought ‘Fairytale Of New York’ on the same day as The Pet Shop Boys’ ‘Always On My Mind’, the single that kept The Pogues off the Christmas number one, without perceiving any contradiction in my preferences, any more than friends who loved Schoolly D and Prefab Sprout or Steve “Silk” Hurley and The Stupids would have. The battle lines were never between music that owed its existence to modernity (samples and synthesisers) and ‘real’ instruments (tin whistles and Les Pauls), otherwise Fairground Attraction would have had the edge over A Guy Called Gerald and Jive Bunny would have trounced The Jesus And Mary Chain; rather it hinged on the same contest fought out in every era – between music made because it is necessary and the kind that simply dances to the sound of sales.

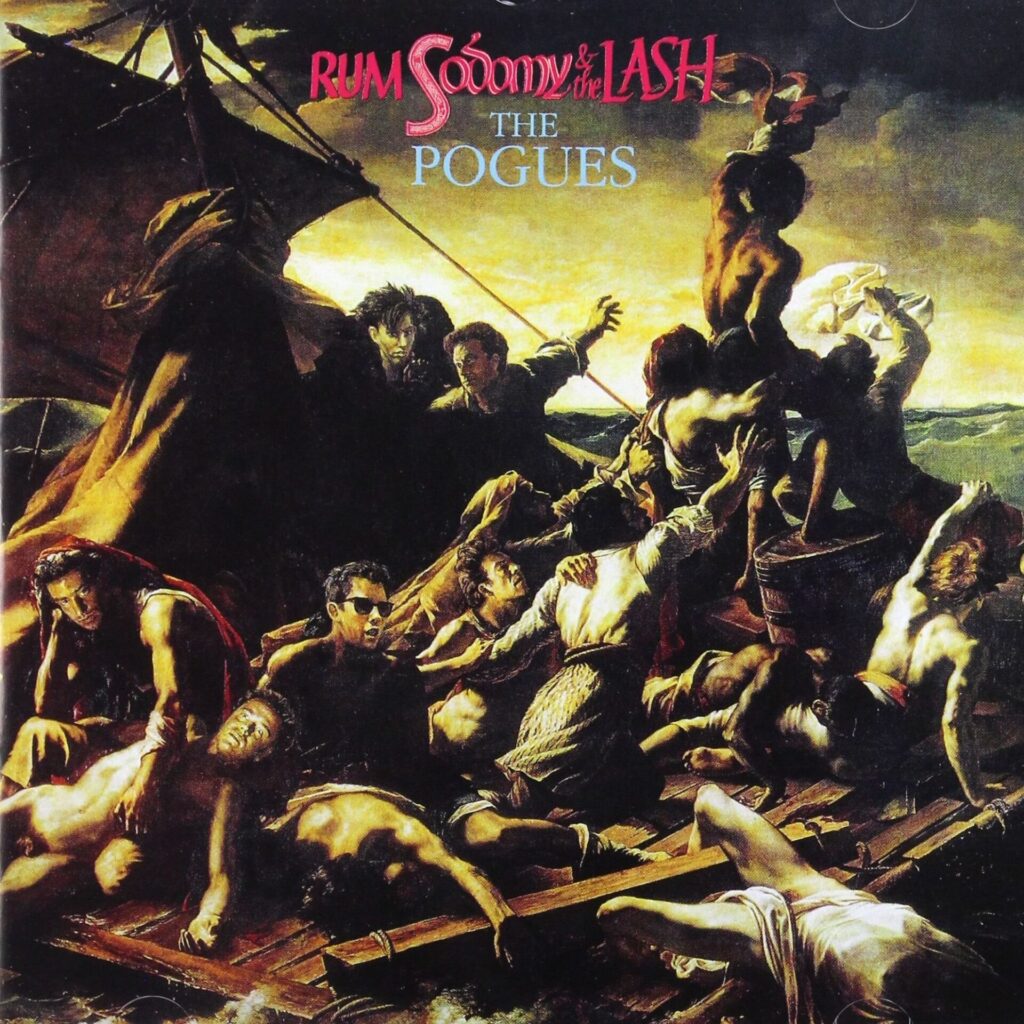

RS&L turned tradition on its head in a manner a generation better acquainted with punk than Alan Lomax’s field recordings understood immediately, even as roots purists dismissed the record as an illiterate and parodic appropriation of Irish culture, and the band as diasporic chancers playing up to offensive stereotypes. In fact the record was both an act of inspired cheek that did not care if it was confused for loutish desecration by the gatekeepers of niche and orthodoxy, and a tribute to those very same orthodoxies by a band that were about to become the greatest exemplars of the living folk tradition. Launched on the HMS Belfast and charting at number 13, its cover a mutilation of The Raft Of The Medusa with the band’s faces superimposed over those of the survivors, RS&L was punk played on traditional instruments that harked back to the Irish show band format with the group sharing the spotlight, save for one undemocratic anomaly: Shane MacGowan. Already a talismanic presence, RS&L plots Shane’s evolution from the band’s shy frontman into a songwriting GOAT. Such is his braying authority, tottering charisma and bardic intelligence, RS&L sounded like MacGowan had written the entire album himself in the time it took the others to get their round in. In fact he penned only half. Even at his peak, he was not a prolific song writer, never responsible for more than two thirds of any Pogues album or destined to lyrically dominate a record as his contemporaries Mark E. Smith and Nick Cave did theirs, over far longer periods of time.

Yet it was impossible for MacGowan to put his voice to a song without it sounding like his. The weakest of the other compositions on RS&L, the stodgy ‘Navigator’ and ramshackle ‘Jessie James’ (sung by Spider Stacy), are still several cuts above ragbag filler, stuffing and miscellany, while the steals from other songwriting giants are inspired acts of creative theft. For once eschewing the work of their spiritual forbears, The Dubliners (while still covering one of their tunes, ‘Gentleman Soldier’, as unhinged slapstick), The Pogues proceeded on the hunch that the majority of their growing audience would never have heard the originals of ‘Dirty Old Town’ or ‘The Band Played Waltzing Matilda’.

The first of these is an unabashed affirmation of socialism-of-the-heart (romantic reasons ought to come a close second to humanitarian ones for anyone entering politics), and MacGowan’s most successful (and popular) appropriation. Ewan MacColl’s original is suffused with great dignity, delivered with the solemnity of a schoolmaster, priest or teacher, whereas MacGowan sings like a labourer in love, in real life and time. We share his cheerful relish as he lifts the “good sharp axe” that chops an exploitative system “down like an old dead tree”, which coming after the evocation of love “by the gasworks wall”, draws a picture of such vividity that I imagined watching the song happen in the dark when I first heard it in bed. ‘The Band Played Waltzing Matilda’, at just over eight minutes the longest song The Pogues attempted, is a pacifist masterpiece and a soldier’s view of history that rumbles along beautifully to its devastating denouement, MacGowan’s advantage over Eric Bogle being that he sounds like he is the mutilated infantryman singing the song cap in hand on the pavement, and not the folk singer who wrote it. The album’s loveliest cover is an innocent trick played by the band on the expectations of the listener. ‘A Man You Don’t Meet Everyday’, sung by the only woman in the group, Cait O’Riordan, is the crack in everything that allows the light in, a masterpiece of poise, suggestion and restraint, and the only Pogues song that would not have been improved if MacGowan had sung it himself.

Having already expressed his genius on feisty rabble-bait like ‘Boys From The County Hell’ and ‘Transmetropolitan’ on Red Roses For Me, MacGowan’s severely accelerated rate of ageing was most noticeable in artistic terms on RS&L (but also physically – just 11 years later he would record his final album, aged 40, sounding as old as Dylan does now) and a progression that fans used to their heroes packing lifetimes into a couple of years took for granted. He was an entropic fireball, and RS&L is the sound of a man impatiently blazing a trail through future resources. For audiences cheering him along, questioning his recklessness would have been weird; rock & roll was not supposed to be a safe space, and putting private demons to public use was de rigueur in a way that has since fallen out of moral fashion. Like a boy growing into clothes already purchased by a hopeful parent, MacGowan’s talent appeared to be waiting for him to claim it, seemingly no more than an extension of the personality that fitted him so comfortably. Suffused with empathic univocity and plain-speaking insight, his new material ranged from ballads other singers would one day sing songs about, ‘A Pair of Brown Eyes’, to snarling riot-acts like ‘Billy’s Bones’ that could not wait to finish the fight. ‘Sally MacLennane’ is a poem slipped into an anthem with a sing-along chorus that must be one of the most rousing ever composed (which ironically made it sound like a cover), a tribute to unguarded sentiment and open hearted revelry, while ‘The Sick Bed Of Cuchulainn’ switches from theology to incontinence, mythology to memory loss, echoing the philosophical concerns of MacGowan’s literary forebears and the arsonist joy of punk; the folk-pantheon in flames as James Fearnley’s accordion squall scorches the rafters.

The stately sincerity of ‘A Pair Of Brown Eyes’, which underwrites its strange and dark surrealism, demonstrated MacGowan’s growing tendency to ignore punk’s minimum speed-limit, while the confidence inherent in slowing the music down reaches its apotheosis in the honest sparsity of ‘The Old Main Drag’. There are few other vocals where the singer makes no effort to manipulate the listeners’ emotions, or even tease any feeling out of the story he is singing, the rendering alone enough for a song that has no need of theatre to realise itself. This is partly because he belongs in that tiny sub-compartment of singers who are poets, their lyrics able to survive scrutiny on the page without sound or music, and this is also why I suspect people who I otherwise rate the opinions of do not rate The Pogues. MacGowan’s literary sensibility, that every Pogues (and Popes) record is saturated in, alienates modernists who dislike humanism in art, preferring their music as a thing – deliberately dumb and vague without a personality intruding, just as others disparage the caricature of Shane MacGowan (the high priest of ‘the sodden solidarity of loserdom’) that they themselves have created. In a manner similar to a novelist he created worlds that reality compelled him to romanticise, and listeners who find this all too much like reading, dislike the cheaply acquired view of the stars alcohol affords, and prioritise songs over whoever happens to sing them, expressed in that voice, are unlikely to give RS&L the benefit of the doubt. Personally I find MacGowan’s much mocked tonal range on RS&L, delivered betwixt a sigh and a snarl, the light and sound and temperature of emotional omnipotence, its all-feeling timbre sustained until Peace And Love, whereupon it dropped into a sagacious growling croak, never to rise again.

RS&L was produced by Elvis Costello, or “Uncle Brian” as the band called him (you either get it or you don’t), with sympathy, economy and love, having the good sense to allow the band to get on with it, as he had The Specials on their first album. The fact that MacGowan appears to have begrudged his presence is a puzzle Costello claims to never have solved and is still hurt by, revering the man and sharing (or so he thought) the same musical values. I have heard it argued that this was a clash of heart (MacGowan) and head (Costello) though this does not really stand up to scrutiny. Recorded just months later, Elvis Costello’s ‘I Want You‘ is as raw as anything Shane MacGowan penned, and the latter’s wordplay on RS&L is as cerebral as the former’s most knotty concoctions. MacGowan never publicly sought to analyse his talent, and certainly never disciplined it, and he may have resented anyone who pretended to, or thought they could. Moreover with the help of Occam’s razor Costello’s courtship and marriage to Cait O’Riordan, who subsequently left the band – whom MacGowan may also have been amorously involved with – would provide further context for their differences. (“I looked at him he looked at me, all I could do was hate him”). It would not have helped that Costello exaggerates his touch when he states that no one ever captured The Pogues “in their dilapidated glory”, as succinctly on record again. They did however, Steve Lillywhite to a poppier effect and Joe Strummer at least as organically, but he is right in as much as he understood the dynamics of the band – if not MacGowan – at least as well as themselves.

For completists the 2004 re-release of RS&L includes the Poguetry In Motion EP and B-sides, which in real time helped feed the misbegotten hope that The Pogues were set to becomes a permanent feature of the cultural landscape for years to come. MacGowan’s compositions are carried on the shoulders of the mellifluous fluency and tightly-drilled anarchy of the band, now joined by Phil Chevron, Terry Woods and a little later Darryl Hunt (who according to our school yearbook was an accomplished cross country runner). ‘The Body Of An American’ is the occasion where the US experience meets the diasporic one, and a uniformed stranger throws his arms around you and persuades you family is a question of choice, whereas ‘A Rainy Night In Soho’, which deserves an essay of its own, is a an auto-recollection of life’s most valuable experience; to love and be loved back. The album closes with ‘The Parting Glass’ (“If I should rise and you should not”), which will surprise no one is the version of the standard I would like played at my funeral. Once again Shane MacGowan is the young man with experiences that belie his age, the song’s sombre presentiment one he has been preparing his entire life to issue, shared here with an unhurried and harsh courtesy as he makes eye contact with the room, finishes his drink, and steps out of the inn to join the rest of the departed in eternity.