It would have been 1992, early that year. It wasn’t the first time I’d heard the song, in fact I’d already had the album it was from for some years and enjoyed it very much already. But arguably it was a moment where it all clicked even more. I forget the exact details, but it was after a show somewhere in Los Angeles, and some friends and I were gearing up to head back or else just to go get a late bite to eat somewhere. It was also a few months into the short life of MARS-FM, a kind of catchall ‘alternative’ radio station that was taking on the utter dominance of KROQ, with a more electronic/ techno bent if not entirely. Much like KROQ they also had a kind of older mascot/spirit animal of a personality anchoring a particular spot – KROQ had Rodney Bingenheimer, while the MARS equivalent was Don Bolles, who had come to California in early punk rock days to drum with the Germs and had ended up in a series of bands since and generally was a guy-around-town in those circles.

Like Bingenheimer, Bolles played pretty much whatever the hell he wanted to, old and new. And like so many of the young musicians in America and elsewhere that got punk-rock-as-such, they were established glam fiends of one kind or another. So it wasn’t surprising that I heard what I heard, but at some point the slow, stately, exciting introduction of ‘Out Of The Blue’, the fourth song off Roxy Music’s fourth album Country Life kicked in on his show. And it felt juuuust right, something fully clicked on a temperate Southern California evening with still a little excitement in the air rather than exhaustion. Andy Mackay’s oboe and Eddie Jobson’s violin, the latter treated to sound like a breathless, swirling wash, playing around each other as Paul Thompson’s drums and John Gustafson’s bass built the rhythm up and up until a hyperactive roll heralded Phil Manzanera shimmering in on guitar while Bryan Ferry added piano and sang: "All your cares/ Now they seem/ Oh so far away!" Now that was a moment and a half, and that was with Jobson’s full seagull-screaming solo and Manzanera’s own frenetically beautiful moments still to come well later into the song.

Roxy Music was always an inherited pleasure for me, something I never knew at the time – when you’re born in 1971, knowing that Country Life was the first Roxy album to go Top 40 on the American charts in 1974 is learned trivia well after the fact, not something a three year old has any sense of or grip on. Ferry’s concurrent solo career; the trans-Atlantic success of ‘Love Is The Drug’; the initial breakup of Roxy; the reformation; ‘Avalon’; the further breakup; that all happened without me noticing. At most I might have seen a mention or two of either Roxy or Ferry here and there by the time of the early 80s. This happened when any number of clotheshorses from (the absolutely fantastic, still) Duran Duran on down started hitting it big in America and there were mentions of just exactly where this approach had come from. It wasn’t until Brian Eno had a short piece on David Lynch’s Dune soundtrack in 1984, that I heard anything with a Roxy connection first hand. And it wasn’t until 1986, when Ferry’s stately ‘Is Your Love Strong Enough?’, featuring an equally stately guitar part from David Gilmour, appeared on the end credits of Ridley Scott’s Legend, that I knew of – and immediately liked – the singer’s own work. It took a 1989 purchase of Avalon, followed soon thereafter by the American CD release of the combined Roxy/Ferry overview compilation Street Life, for me to start to take a full plunge, though, but then I was off to the races. And all this time later I’m still there (he said, counting the days to the release of Ferry’s Avonmore at the time of writing).

I ended up picking up the rest of the Roxy albums one by one in order of original release – a very self-consciously scholarly move, but I remember doing the same thing with the Velvet Underground around the same time, while the recently launched David Bowie CD remaster series forced me to do similar by default. Of course, as I found later, the subtitle on the back sleeve wasn’t just for the CD reissue, or even limited to this album alone – this wasn’t simply Country Life, this was Country Life: The Fourth Roxy Music Album. This kind of statement-of-intent as both something factual and something driving a further presumed narrative appealed to the part of me that wanted to get everything just right and just so, the part of me that would construct best-of lists to come in the future for yearly releases and all. You couldn’t pay me to do that now, and similarly I just think of Country Life as its own thing. In fact, most days I feel it’s the best of them all.

Which may or may not be surprising. Conventional wisdom – at least so it seemed to me at one time – held two separate album peaks for Roxy: the explosive and unsettled first two albums with Eno, the first edging out the second, and Avalon as conclusive final perfection of ennui and elegance following the adjustments of Manifesto and Flesh + Blood. Perhaps tellingly, at least on that specific American CD release of Street Life I mentioned, Country Life was the only album that didn’t feature a song on the tracklisting. But right from the start it was Country Life that I ended up taking around with me, playing around at various locations. I listened to just about all of them equally, at least when it came to the first four. Siren always felt a little choppier in comparison and the final three their own contemplative listens. But I have memories of working in a library warehouse facility, my college student job, alone aside from a slew of books and empty shelves, merrily blasting ‘Prairie Rose’, Country Life‘s actual country (or at least country rock) song. With its twangy steel guitars and rollicking piano and pace sounding like it’s coming out of a open-top convertible barrelling down a freeway. It features Ferry regularly going "Texasssss!" in a combined whispered come-on and invocation. It’s such a great way to end the album and, of course, it quite sounds like nothing else that came before it. In fact nearly everything on Country Life does a fantastic job of not fully resembling anything else it shares album space with despite the fact it’s the same band, the same singer, just doing their thing. Amazing stuff.

Inasmuch as I have a theory about what was going on, it’s that everything had gelled, just right, for that second, post-Eno era of the band, in recorded terms at least. With the previous year’s Stranded, the addition of Jobson’s violin work on top of synthesiser performances (as a new and distinctly different wild-card element in place of Eno’s own experiments), Roxy avoided issue of simply going for a clone of the first two albums. Instead they were harkening back perhaps to John Cale in and out of the Velvet Underground as a reference point. Meanwhile Gustafson – who sadly died last month – might just be the most underrated member of all the Roxy incarnations in the end. Like Jobson he was a presence on the stretch from Stranded to Siren, playing that killer bass line on the latter’s ‘Love is the Drug’ that defines the song after Manzanera’s brief chord, on this album doing things like a quick, nervous break moment on ‘Out Of The Blue’ to let you know he’s there without having to steal the show. Add their skills to the core of the group and open the album with ‘The Thrill of It All’ – serving as yet another couldn’t-be-better album opener after ‘Re-Make Re-Model’, ‘Do The Strand’ and ‘Street Life’ before it – with its stirring yet strange introductory piano and then Ferry’s wordless descending vocals echoing through the swift rampage of the arrangement, it’s basically Roxy Music in excelsis. It’s the sound of a GREAT band that just happens to have all this other cultural context feeding into and out of it.

That was always part of the Roxy mission as such, of course, and not just from Ferry’s point of view – whether it was the fashions or the pop art nods, the cinematic references or the literary ones, in the case of ‘The Thrill Of It All’, the closing line from Dorothy Parker’s brilliant Résumé: "You might as well live." But that perfect moment of going on no matter what, wittier than dull existentialism and with as much joie de vivre as you want to bring to things, almost sums up the album’s tactile thrill: live and do it all, and there’s everything from cool regrets to hyperactive energy, snotty dismissiveness and love-drunk desperation. A later generation might call it first world problems run rampant, but the voice was still the miner’s son thriving in a postwar assumption of broader education and aspiration, elegance as signifier in response to unwritten sartorial laws and codes, a Gatsby who didn’t have to worry about rum-running and was all for a slew of green lights all over the place.

Ferry is in compositional control throughout but the collaborations all make perfect sense, two with Mackay and two with Manzanera, ‘Out Of The Blue’ and ‘Prairie Rose’. Of Mackay’s, ‘Three And Nine’ lets him bust out a great sax solo while Ferry adds in winsome harmonica, a fake-out ending, and the how-the-hell-had-nobody-done-this-before line, "I’m not so special/ You’re a misfit too." On a completely different note is the second collaboration, the none-more-melodramatic ‘Bitter-Sweet’, icy, arch and utterly dismissive, like The End Of The Affair but as if written by Isherwood instead of Greene. It shows a relationship as performance (and love as a selection of wines) and has counterpoint verses with violent guitar and stomping beer hall rhythms and a full section in German for good measure. Mackay’s oboe adds only a small amount of gentle balm – if that – as Ferry tremulously concludes: "And now, as you turn to leave/ You try to force a smile/ As if to compensate/ Then you break down and cry." Not that he actually sounds sad himself… or does he?

In the meantime there’s another halfway to down-home ramble in the form of ‘If It Takes All Night’ as Ferry and crew are relocated from the shores of Newcastle to somewhere near New Orleans. Also there is the none-more-stately/heritage music turn of ‘Triptych’ letting Mackay sound like he’s playing crumhorns for Queen Elizabeth while beating the Rolling Stones’ ‘Lady Jane’ at its own game. And of course there’s the royal progression of Ferry’s vocals across the stereo panning, not to mention ‘Casanova”s swaggering and menacing funk which is at once ugly and impossible to ignore, with lines such as "Now you’re flirting/ With heroinnNNNnnn…or is it COCAINE?" being spat out. ‘A Really Good Time”s late-evening, doom-tinged cocktail-lounge elegance, strings punctuate the end of each verse with a sit-up-straight punch, and Ferry giving into the kind of hysterical edge familiar from the first album’s ‘If There Is Something’, trying to convince somebody about it all but most clearly trying to convince himself. (And this after delivering lines like "All the things you used to do/ A trip to the movies, a drink or two/ They don’t satisfy you/ They don’t tell you anything new" and "You know I don’t talk much/ Except to myself/ Cause I’ve not much to say/ And there’s no one else." They pinpoint perfect moments, short stories in hyperminiature.) It’s not a question of deep cuts here, more like how each one is a necessary facet of the whole, a huge world within two sides of vinyl.

If there’s a note-perfect song on a note-perfect album, though, it might have to be ‘All I Want Is You’, three songs into the whole thing and so perfect it’s no surprise Country Life almost feels front-loaded. Manzanera’s introduction is a fanfare for six-string and feedback; and from there it’s another quick stomper, fast and fun without being ponderous or simply skipping by, Ferry splitting the difference between main verses and breaks and making both equally memorable and immediate. There is a full instrumental section that lets everyone show off collectively, while still wrapping it up in three minutes. And all the while Ferry deliciously – there’s no other word for it, he sounds like he’s savouring every last syllable as he delivers it – seems to just throw out lines like, "If you ever change your mind/ I’ve a certain cure/ An old refrain, it lingers on/ L’amour, toujours l’amour" and "Don’t want to know/ About one-night-stands/ Cut-price souvenirs/ All I want is/ The real thing/ And a night that lasts/ For years." Take it at face value, read it all as a ploy, or both, it all works, and when he bows out with "Ooo-oo, I’m all cracked up over you!" there could be no finer flourish; his heart, or something close to it, worn on his sleeve.

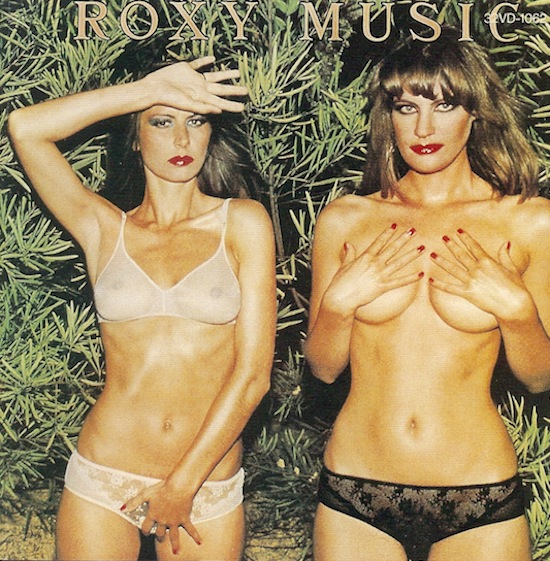

And speaking of sleeves, I can’t not mention the actual cover art itself. Appropriate given that the album specifically referencing a British magazine of the same name, all veddy English and proper about rural life, another bit of aspiration that Ferry and company proceeded to pulverize and celebrate all at once. The result: the male gaze and then some, one year before Laura Mulvey coined the term. Not that Roxy hadn’t already been associated with this kind of idea given their three previous covers, of course, but when you have two women on the front, one woman using her hands in place of a bra, looking directly out at the viewer, another with a bra that leaves little to the imagination but while holding a hand in front of her panties just so, also giving you a direct look back as she holds her other arm to her forehead, it’s a little hard to miss. Ferry met Constanze Karoli and Eveline Grunwald on a Portuguese trip, persuaded them to do the cover, British Vogue photographer Eric Boman did the shot and the rest was fairly notorious history, ranging from alternate cover shots of just the background trees following refusals to stock the album to innumerable parodies and references from other bands and publications in later years and more from there.

Saying everyone involved knew exactly what they were doing might be too much for anyone to claim – but then again, the shot used did have them both looking right out at any viewer, and their look was not so much inviting as challenging, even cold. One other detail too: Karoli and Grunwald are both specifically credited on the album’s inner sleeve with helping Ferry on translating the German verses for ‘Bitter-Sweet’. That Ferry’s son became famous – or infamous – in later years with the kind of talk about fox hunting that might as well have come from the actual Country Life magazine being referenced seems perfect irony, but that’s the danger of aspiration and subversion in the end, when everything becomes heritage history, even when it still works on a late night evening out on the town thousands of miles and two decades away.