There’s an idea circulating in theoretical physics that suggests the Big Bang birthed two universes – ours, with time moving forwards, and a ‘mirror universe’ where time flows backwards. As is so often the case, science fiction got there first in trying to imagine what a reversed existence would look like (Philip K. Dick’s Counter-Clock World for instance). At first, it seems a revelatory conceit that turns all of our norms (cause and effect, ageing, eating, procreating etc) on their head and allows us to see them afresh. Yet, it quickly exhausts itself and even when illuminating a subject as disturbing as the Holocaust (Martin Amis’ Time’s Arrow), it’s difficult to sustain and hold together as a coherent form. To fully inhabit such a world, we would need to think in reverse, something that is as difficult if not impossible to us as thinking forwards would be to readers in the mirror universe.

Despite these reservations, we persist in trying to do this to other people’s lives, especially once they end. The tragedy of death – particularly when a person dies young – casts a shadow backwards over everything they did or were. Conveniently setting aside contingency, their death serves as a retrospective confirmation that they were always going to die that way, a deterministic certainty from the beginning of the universe itself to the final heartbeat. It doesn’t matter that things could have been different, that choices are made, that retrospective determinism is a logical fallacy, or that quantum mechanics calls into question providence and the idea of a clockwork universe. Above all, none of us live as if we have no free will or are allowed to live that way. Fate, and even doom, is something we confer upon others – the heroes, martyrs, villains, and the damned.

Elliott Smith is one such figure. There’s no getting away from the hell that he went through and the horrific manner in which his life ended, at the age of 34. The danger is in reducing a multifaceted contradictory individual and artist into a trope, a cipher to serve our purposes and biases – the patron saint of sad boys, chronicler of the fucked up, who got too close and felt too much. Via his musical palette and immaculate guitar playing Smith was dubbed Nick Drake for Generation X. While both are still under-valued as guitarists, Smith rejected this role as much as Drake would no doubt have rejected our mythos of ‘Nick Drake’. When a figure is canonised in such a way, their humanity is discarded. At the very least, a back catalogue of such bewildering musical diversity, that it beggars belief it came out of one man and not a Beatles-sized group, is exchanged for a paltry Xeroxed forgery, without colour and life. In the same way as dismissing Leonard Cohen’s music as depressing or Tarkovsky films as boring, all it reveals is that some critics are intent on not seeing different important aspects of life.

Released 30 years ago, Elliott Smith’s self-titled basement-recorded second album, with its many references to drugs, drink and life at the edges of society, is the one that the cultural morticians reach for to suggest his fate was always sealed. It matters little that it was released eight years before his death, with three far more lavishly orchestrated albums released in the intervening time with another in process. It’s no accident that one of his posthumous biographies is called Torment Saint because that’s what was required. You could blame Wes Anderson. The first time many people heard of Elliot Smith was the inclusion of the self-titled album’s opening track ‘Needle In The Hay’ in the film The Royal Tenenbaums (2001). Before recording this song, Smith had already recorded several commendable albums with his band Heatmiser that had failed to fully ignite, and a solo album Roman Candle (1994) that felt more like a collection of demos than a debut proper. There had been hints of what was to come, though. Heatmiser’s ‘Plainclothes Man’, for example, shows his talent for wrapping anguish and rage in the prettiest and catchiest of melodies. The righteous venom and menace of ‘Roman Candle’ demonstrates emotions that he would struggle to contain, hence the self-medication and instability that would follow but the intricacies (baroque in lesser hands) of the very next song, ‘Condor Ave’, shows precisely how he would do so – by writing sensitive, honest, sophisticated indie folk/pop music. Yet it was ‘Needle In The Hay’ that would become both the entry point and a kind of drogue continually pulling him back. It works well in the film but too well for Smith, immediately assigning him to archetype status – when the gateway song for your career is saturated in drugs, it’s hard to turn back or start again. If a die was ever cast for Smith, professionally at least, it was this, and all the pop magna opera he produced and mastered afterwards couldn’t shake it off.

The weakness of this view is that it is too singular and attributes autobiography where there may simply be storytelling. It could be that friends and collaborators from that time are being kind and loyal when interviewed, saying that drugs were not a huge, visible presence in Smith’s life at the time. Yet it is clear Smith gathered a lot of material from his surroundings, as much as his feelings and interiority, and was a keen-eyed observer of the endemic social problems and temptations besetting Portland at the time. The album was very much a portrait of a city. It was also analogous. In times of censure, artists have long referred to drug use via metaphors, where God or love is a substitute, usually, for heroin. It’s less usual for artists to reverse this and explore religion or romance via the metaphor of junk but there is plenty of evidence that Smith did so at the time.

An example is the thematic searching innate to ‘Needle In The Hay’. An unlikely precedent to this can be found in the melancholic tale of Ann of Oxford Street in Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions Of An English Opium-Eater, which describes the disappearance of his love forever in the tumult of the metropolis – something that was very much possible, pre-internet – her absence remaining his “heaviest affliction” decades later. On Smith’s track, the act of searching is implicitly manifold – the needle might be love, drugs, money, hope, someone to shake down, something or someone (even yourself) who has been irretrievably lost. The Velvet Undreground’s ‘Waiting For My Man’ is an explicitly stated ancestor, “6th and Powell, a dead sweat in my teeth / Gonna walk, walk, walk / Four more blocks, plus the one in my brain / Down downstairs / To the man, he’s gonna make it all okay”. A guy searching for a fix that will, for a while, bring an cessation to the need to search, an escape from thought, anxiety, memory and the self, but always in a cruelly temporary sense. “I’m taking the cure” he sings “so I can be quiet wherever I want”, with the implication that the cure is worse than the disease.

Lou Reed was a voyeur too – he alternated between concern and callousness when it came to Lisa, Stephanie, Candy and so on – as well as a participant. There’s no seeing without some kind of doing, no interiority without some kind of exteriority. When you’re in that world, you’re in it. Escape is thus another theme, however possible it might or might not be, or how wished for. When you listen to the proximity of Smith’s voice in ‘Needle In The Hay’, close enough to be in the room, the serpentine hiss he makes after the acidic humour of, “You oughta be proud that I’m getting good marks”, it’s as soothing and disturbing as the drug it channels. The double-tracked whisper of his voice a reminder of the etymological origin of morphine – the god who shaped blissful dreams one might never wish to wake from. It would be an exceptionally dangerous flirtation, as would the idea that the good stuff, in terms of creative inspiration, comes from bad places.

Things are not necessarily what they seem, though ,in Elliott Smith’s songs. For many years, I’d assumed ‘Christian Brothers’ was about institutionalised abuse. It turns out that it refers to a type of brandy and is about, as intimated by ‘Roman Candle’, standing up to Smith’s abusive step-father. Yet there’s delusion and bravado too, “No bad dream fucker’s gonna boss me around / Christian Brothers gonna take him down” before acknowledging, “But it can’t help me get over”. Later, there’s the painfully self-aware admission, “This sick I want” and “nightmares become me, it’s so fucking clear”. There are times later in his career when acoustic versions of ornate electric/orchestral songs came to light – ‘Son of Sam’ for instance – presenting a different incarnation of a song the listener assumed they already knew in full. With ‘Christian Brothers’, this was reversed with the posthumous release of an early Heatmiser version. You could hear how Smith buried trauma under superlative production and multi-tracked instruments, hiding pain inside a mixing desk, something that increasingly happened after this self-titled album. Halfway through the band’s version, there’s a concentrated bombardment of heavy guitars, as if trying to erase the song and its subject entirely, trying to escape not just the discomfort of memory but being defined by what you has damaged you, and then, in true Elliott Smith fashion, a solo as clean as birdsong.

The opening verse of ‘Clementine’ is worthy of a first-rate noir novel or an Edward Hopper painting. “They’re waking you up to close the bar / The street’s wet, you can tell by the sound of the cars / The bartender’s singing ‘Clementine’ / While he’s turning around the open sign”. Smith never released a bad or even a mid major album, which is a surprisingly rare thing to say and sadly points out how foreshortened his recording career and life were. In terms of impact and arrangements, the albums that followed this self-titled record boast higher peaks. Yet this is his most consistent and consistently brilliant, without a misstep in its running time. This is partly due to judicious editing with many of the discarded outtakes that resurfaced on New Moon and deluxe editions being quality but superfluous excess. His last album Figure 8 was astonishing at its best but dipped in the middle of its 16-track overspill. More than that, the self-titled album sustains a voice and atmosphere throughout that is a self-contained world. It is like a musical immersion in night, a nocturne in 12 parts, set in different places and populated by an assorted cast but always after dark. ‘Clementine’ is adeptly situated in that nocturnal world, alternating between dissolution (“You drank yourself into slow-mo”) and pureness (“Made an angel in the snow”) in successive lines. This duality is evident in the singing bartender, the loyal companion to the drinker provided they keep paying for the depressants necessary to placate their blues, and in the song he sings, ‘Oh My Darling, Clementine’, which is superficially a song about lost love and grief but which often has a mocking bathos to it. Playing on a perfectly out of tune guitar, Smith has the narrator try to ease his doubts about his erstwhile lover (“Though you’re still her man / It seems a long time gone”) and failing to do so settles for anaesthesia, “Anything to pass the time / And keep that song out of your mind”.

A different way of seeing Elliott Smith is that it’s transitional. The subsequent two songs ‘Southern Belle’ and ‘Single File’ hark back to the raw and direct Roman Candle but they have maturity where that collection felt at times like juvenilia. Both songs are full of fury, albeit sweetened with the melodic ornamentation he was coming to excel in. The former is like an accusation nailed to a church door, presumably directed against his loathed stepfather’s treatment of his mother (“How come you’re not ashamed of what you are?”) The latter is a portentous dismissal of a junkie acquaintance or perhaps himself (“You idiot kid / Your arm’s got a death in it”). Both do feel bitterly personal, featuring the Elliott who eventually recoiled from an upbringing in Texas (“I live in a southern town / Where all you can do is grit your teeth”) but found himself among, sometimes gifted, deadbeats and deadends (“Here in line where stupid shit collides / With dying shooting stars / All we got to show what we really are / Is the same kind of scars”) with whom nonetheless he develops an affinity.

‘Coming Up Roses’ is different. It looks forward to the more commercial multi-instrumental pop sensibility of Either/Or and XO (channelled from his love of The Beatles, The Kinks, and Big Star) but its attraction hides thorns. Its romantic title isn’t untruthful, but it is checked by a grave note that we all end up fertiliser, literally or figuratively buried in our problems. Meanwhile, junk is present, even personified, throughout: “Your cold white brother alive in your blood”. Smith’s acute awareness is such that the listener may wonder if it’s even a good thing and not a burden, “The things that you tell yourself / they’ll kill you in time”. There’s a very old tradition, going back to the Sibyl at Cumae, of prophets seeing too much and wanting to die. Self-disdain (“I’m a junkyard full of false starts”) alternates with defiance, even if all that amounts to is evasion, “And I don’t need your permission / To bury my love under this bare light bulb”. In the distant past, the moon was the epitome of poetic mystery, before it was revealed to be a cold dead rock, slipping into ignominy as evidenced by Philip Larkin, fumbling back to bed from a piss, staring at this “lozenge of love”, first in scorn until other feelings steal upon him. This fallen moon appears over and over on Elliott Smith, exchangeable with a light bulb or a sickle cell, the quintessence of cold comfort, watching everything that happens and offering nothing but a pale echo of light.

The lunar reappears on the delicate moon-bathed waltz of ‘Satellite’, though it’s not clear if the “burned-out world” it refers to is earthly or our nearest neighbour. With ‘Alphabet Town’, we reach the deepest part of night, the most nocturnal of the nocturnes. Every song on this album places the listener in a different space but it’s always nighttime – staggering between headlights, a starkly lit crack den, an unlit bedroom with a train passing by on an elevated track like the floating cinematic harmonica throughout the song. It’s a character study of a semi-imaginary New York, and its denizens like ‘Constantina’, recycled from pulp or punk, but made real by the intimacy of his voice and the recurring image across the album of “her hand on your arm”, so simple and tender as to be facile in another circumstance but amplified into the sacred here by the squalor of the context.

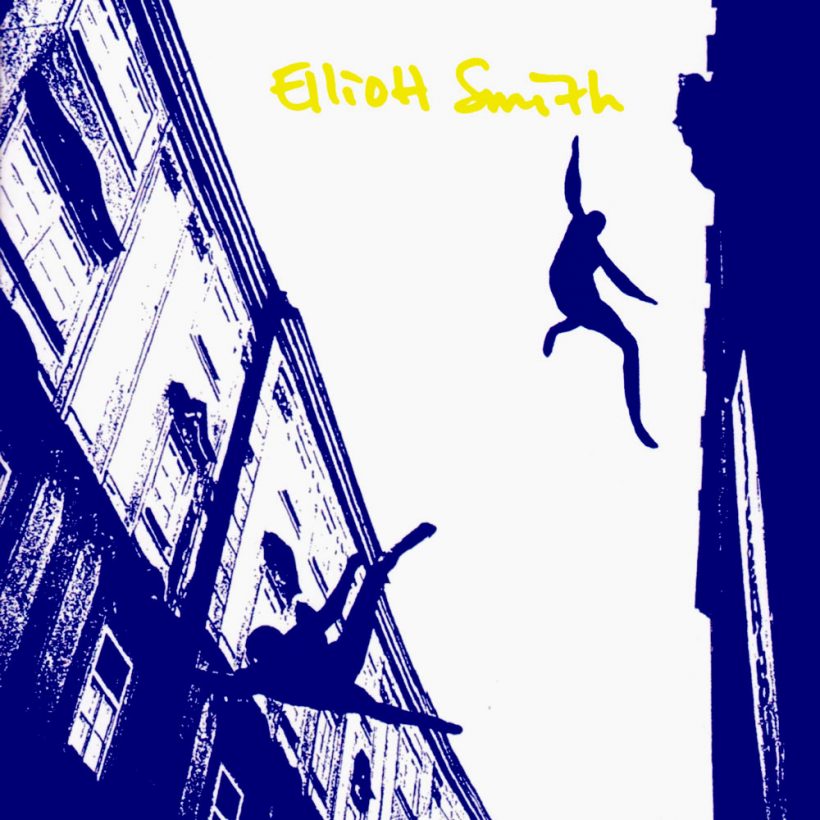

Smith was aware of the emerging view of him, cultivating it to some extent; choosing that album cover with its plummeting silhouettes was a statement, even if it was just a chance snapshot he happened to like of a sculpture in Prague. In ‘St. Ides Heaven’, one of the album’s high points, he challenges the sad boy cliché and the idea that confessional always has to be grim or morose, “You see me smiling, you think it’s a frown turned upside down”. Friends and colleagues from this time continually emphasise how funny he was, and Smith heads off his more morbidly inclined critics at the pass, “Cause everyone is a fucking pro / And they all got answers from trouble they’ve known / And they all got to say what you should and shouldn’t do / Though they don’t have a clue”. Aided by Rebecca Gates of The Spinanes on vocals, the song is as upbeat as one might expect from a song that has a chorus beginning, “High on amphetamines / The moon is a light bulb breaking” and where the saint in question is a bottle of malt liquor. If it’s channelling Wilde’s gutter and the stars, it’s with a recognition that debauched romance isn’t what it used to be in the days of elegant dandies, “I’ve been out haunting the neighbourhood / And everybody can see I’m no good”. There’s an insolence there though, like the moon he “won’t come down for anyone”, even if it means self-destruction.

Of the remaining songs, ‘Good to Go’ and ‘The Biggest Lie’ are hushed laments. The former begins like a chivalric medieval song before the unexpected grit of the opening line, “A low riding junkie girl / Rode down south to your little world like a dream”. The track has an Ouroboros circularity at times then suddenly breaks into an approximation of a speeded-up waltz (few modern musicians were so prone to and successful with the waltz form and its variations as Smith, even if dancing couldn’t be furthest from the mind), peaking with one of his unbearably sublime moments in “She kicked New York like a curse / And you traced her footsteps in reverse up to Queens”. The whole thing has an off kilter unbalancing effect, always cresting and falling, Icarus plummeting seaward not because of the sun but because he suddenly realised who he was. ‘The Biggest Lie’ offers equally scant relief. You could see “I’m waiting for the train / The subway that only goes one way” as just an observation but less so “Now I’m a crushed credit card registered to Smith”. From online readings, the interpretation of what ‘the biggest lie’ of the song actually refers to generally, is a false proclamation of love but it might equally be the opposite. The cursed solitary moment when you tell someone you don’t love them so that they’ll leave you and your demons. The sweet homeliness of the music, especially in the solo, shows the abiding lesson Smith learned from one of his idols John Lennon, post Plastic Ono Band, to sweeten the more troubling messages with sugar coating, and few artists were as bittersweet as Smith.

One masterpiece – maybe the masterpiece – of the album is ‘The White Lady Loves You More’. Again, it has that characteristic waltz feel that’s unusual for modern alternative music and for the modern city that it encapsulates. He informs us: “You wake up in the middle of the night / From a dream you won’t remember flashing on like a cop’s light”. It’s a song of sadness, serenity, masochism, and finally resignation: “I’m looking at a hand full of broken plans / And I’m tired of playing it down / You just want her to do anything to you / There ain’t nothing that you won’t allow”. In many cultures across the world, the spectral appearance of the white lady is traditionally a warning of tragedy to come. Here she is, of course, a personification of heroin, a sign of our degenerate consumer age, as William S. Burroughs put it: “The junk merchant doesn’t sell his product to the consumer, he sells the consumer to his product. He does not improve and simplify his merchandise. He degrades and simplifies the client.” What is her love then? It could be the gift of prophecy, the portent of bad times ahead, or it could be the opiate embrace that temporarily melts away all troubles, while making them grow ocean-deep in the long run.

The albums to come would contain wonders. They would be relatively maximalist, hi-fidelity, widescreen and technicolour. It’s worth wondering if his experiences with Dreamworks and the Oscars did more harm to Elliott Smith than good. They would hide the traumas and addictions well – the perky McCartneyesque ‘Baby Britain’ with its “sea of vodka”, ‘Ballad Of Big Nothing’ where nihilism sounds like triumph (“you can do what you want to / there’s no one to stop you”), the exhilarating psychedelia of the otherwise chilling ‘Everything Means Nothing To Me’, the utterly delightful ‘Waltz #2’ that is nevertheless completely dejected. You could even listen to ‘Between The Bars’ and think it was a love song from another human being rather than alcohol itself whispering sweet nothings to him. By comparison, Elliott Smith is stripped right down to its essence. It’s an exceptionally brave album in this regard (this was the year of ‘more is more’ albums like Mellon Collie…, Astro-Creep: 2000, Disco Volante), and his live shows at the time were even more so, relying on nothing but voice and guitar and songs designed to be so intense you could hear a pin drop, which took far more courage than going on with a loud and disorderly slacker band. Yet it also meant that Elliott Smith is a vulnerable album in more ways than one. By being so exposing, some listeners will be tempted to abandon the positioner of listener for the role of psychoanalyst, moralist, or even coroner, in order to find out ‘what happened’. Conclusions will be made and what is more conclusive than death? The end changes everything that came before it. What if, however, that’s a distorting prism encouraged by our backwards-facing memory and confirmation bias? Another theory circulates in physics that all of time, past, present and future is happening simultaneously, a view that is closer to the spirit of Elliott Smith, where nothing is settled, preordained or one-dimensional, where the debased, the romantic, the dysfunctional and the sublime are all taking place right now, here and always.