In his exquisite 1985 book Final Cut Steven Bach talks about the creation of Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate and his involvement in due to his work at United Artists. It’s of the strongest, most perceptive volumes about the strongest period of Hollywood ever written by someone who was a high level studio executive. It’s also a key survey of the final years of the seventies into the very early eighties when it comes to Hollywood, talking up what would later be seen as the end of a golden age. Happily, Final Cut has the perspective of direct participation and relative recency rather than the rose-colored memories, strutting machismo and worshipful distance that shaped later efforts to discuss the time.

As such, Bach maintains a running narrative about the other films that his studio was involved with. As the wheels grind into motion for Heaven’s Gate itself, he takes a break to discuss where things stood at the end of 1978:

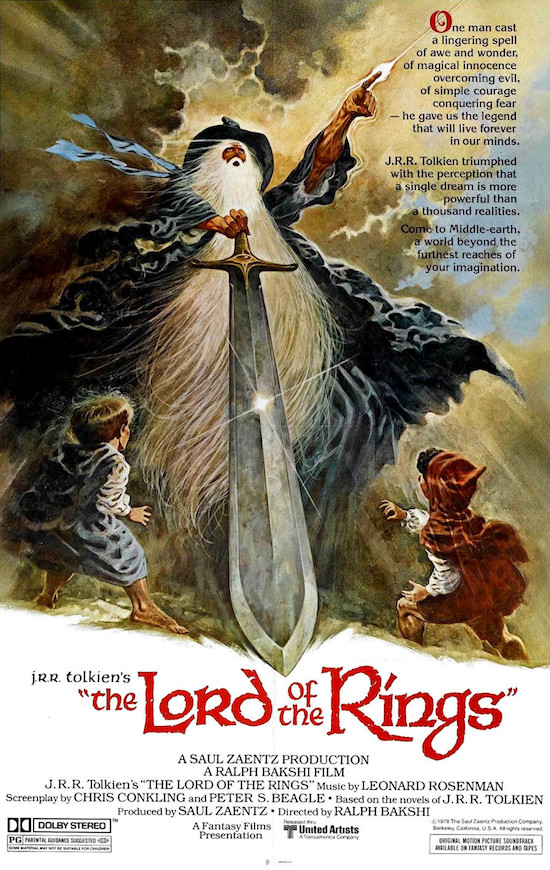

Christmas is, with summer, one of the two big seasons in the movie business, and Christmas 1978 had not been outstanding for the company. Lord Of The Rings led the holiday list, based on the trilogy by J. R. R. Tolkien that had been on and off the UA shelf for a decade. At one time it was intended as a live-action picture from director John Boorman; at another, an elegant Peter Shaffer script of the worldwide best seller was to guide the Hobbits to the screen; at still another, plans bubbled for a multimedia musical extravaganza scored by and starring the Beatles, whose decision not to regroup after their 1970 breakup put an end to that. Finally, Saul Zaentz, the head of Fantasy Records, who had financed and coproduced One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, repeated these chores with Lord Of The Rings and brought the tales of Middle Earth to life with Ralph Bakshi’s amalgamation of animation techniques that were sophisticated, admired, and failed to overwhelm audiences at Zaentz and UA had hoped.

Bach’s narrative continues from there, and Bakshi’s Lord Of The Rings adaptation becomes, in this story as well as in larger Hollywood history, an anecdote, practically a footnote. Bach’s diffidence comes from the mid-80s perspective that the film was at most a failed attempt to ride on Star Wars‘s coattails to at least some degree. Said perspective held that successful Anglophonic film fantasy, by and large, would take the route of Lucas’ space operatics, Stephen Spielberg’s winsome dreams and scary thrills, maybe the occasional surprise like John Milius’s breakout adaptation of Conan The Barbarian, bringing sword-and-sorcery to a new cinematic level. Rip off or repurpose elements of Lord Of The Rings, sure – three years after Bach’s book was published, the Ron Howard-directed Willow did just that – but the attempt had been made, in seemingly the only practical way to try it, and it wasn’t a true smash.

Of course, fast forward some twenty years and Bakshi’s Lord Of The Rings became a footnote twice over. In the wake of Peter Jackson and company’s astonishing and undeniably successful three film adaptation, and all its attendant rewards and honors, Bakshi’s effort practically disappeared. Not entirely, to be sure (not when Warner Bros. made sure to get it out on DVD soon before the first of Jackson’s films was released). Jackson noted that the first time he read the book it was a tie-in effort featuring Bakshi’s film art on the cover, and freely said at least one of his scenes paid specific homage to the earlier film’s approach. Bakshi and others thought they could spot further instances, while the older filmmaker, with understandable enough grouchiness, spoke out at points about what he thought was a too-convenient glossing over of his work and that of his team in the wider public sphere.

There just might be a connection. Via The One Ring

But mostly the reaction to Bakshi’s version by that point could be summed up by what actor Sean Astin said in his own memoirs about working on Jackson’s version, called There And Back Again. Speaking of his efforts to read the original text before filming – which he did eventually do – so he could get a deeper understanding of his character, the loyal Sam Gamgee, Astin admitted to initially taking a ‘shortcut’ and watched a video of Bakshi’s adaptation. His response?

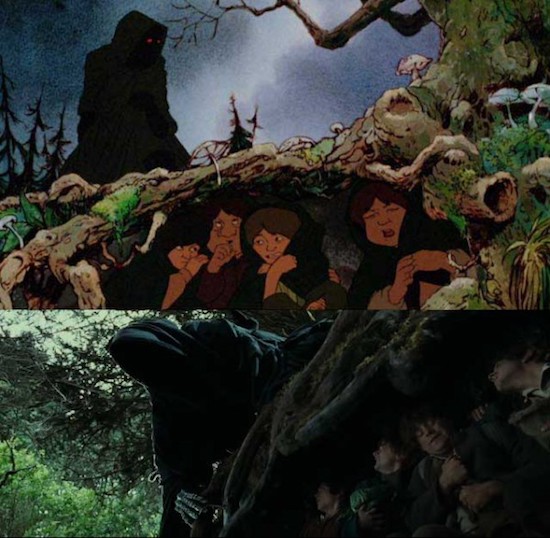

Seeing how Bakshi portrayed the hobbits – as predominantly fat, bumbling, stupid characters – I nearly had a heart attack. Please, God, don’t let Peter Jackson approach it this way. I should have had more faith, but it was too early in the process. I wasn’t sure what Peter had in mind, and I knew that Bakshi was far from a hack. He had his devotees, and I’m sure he knew the story and felt that his was an entirely appropriate interpretation. Moreover, the animated version had its moments. The ringwraiths, for example, were spectacularly depicted. I could appreciate what Bakshi was trying to do as an animator and a storyteller, but I was concerned mainly with Sam and how he would be portrayed… I wanted Sam to be heroic and strong, to have integrity. He was a gardener, a working-class man… There are probably thirty valid ways to depict the hobbits. But I had my own idea of how I wanted Sam to be perceived, and it was set in concrete. What I had in mind wasn’t that… that thing, that animated oaf on the videotape.

Yeah… oaf is the word. Image via Reddit

Astin’s take wasn’t the sole or predominant one but in terms of structure it arguably matches the general reaction to the film over the years: ‘Boy there’s a lot of… stuff here. At least you tried?’ Set between the tension of a rabid, worldwide fanbase steeped deeply in an ornate and detailed adventure and a public wanting to be entertained regardless of the source, Bakshi’s effort made some money and resulted in occasional praise here and there, though sometimes grudging. Following Jackson’s triumph, even that dissipated to a near-complete degree.

Not totally, though, and now, on the fortieth anniversary of Bakshi’s effort, it would be too much to say that the film either needs or deserves a total rehabilitation. As Astin notes, it’s always had its devotees, drawing on followers and fans of Bakshi as much, if not more so, of Tolkien. But perhaps now is the time for a greater contextualisation of the film in turn, because practically speaking, not only was it an incomplete effort – ultimately the first of what Bakshi felt was a necessary two-film effort which was never undertaken – it rubbed up against four other adaptations of Tolkien’s major works within a four year span total. These other productions – there were two productions made as American TV movies by the Rankin-Bass animation studio, an American radio production and a BBC radio drama – are as relevant to the story of Bakshi’s Lord Of The Rings, its perception and reception, as Bakshi’s own run of films through the seventies into the early eighties.

Then there was the new Mighty Mouse stuff Bakshi did later and the sniffing-flowers-or-is-it-pink-cocaine controversy. The eighties were weird. Image via TheBoronHeist

To delve into a full study of all Tolkien adaptations, proposed or released, would be beyond the scope of this essay. (Did you know about the 1985 Russian TV movie of The Hobbit, for instance?) Frankly speaking, even a dyed-in-the-wool Tolkien reader like myself still has trouble determining the story of the Tolkien adaptation rights, which has now reached a new peak with Amazon’s headspinning $250 million commitment to the Tolkien estate last year. So best simply to start here – in 1977, a full year before Bakshi’s film debuted, and four years after Tolkien’s passing, the first of the two American TV adaptations took a bow: The Hobbit, as produced by the noted TV animation team Rankin/Bass. That duo had made its name over the years through a variety of stop-motion animated specials, notably its loosely interconnected Christmas shows, famously begun with the Burl Ives-narrated Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer. The Hobbit was done as conventional painted animation, but with an interesting twist: while Rankin/Bass oversaw the concept art, actual production was handled by Topcraft, a noted Japanese animation house of the era.

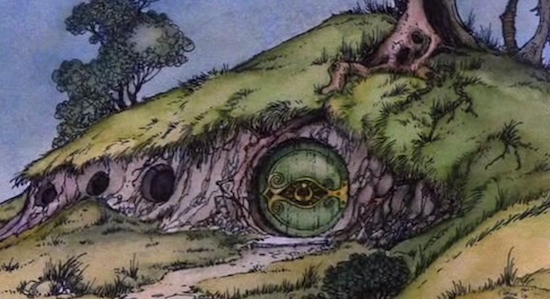

Topcraft grew even more notable some years later when it dissolved and then, renamed, reformed under one of its regular animators – a certain Hayao Miyazaki – leading to Studio Ghibli’s still striking run of animation landmarks. Miyazaki himself didn’t work on The Hobbit, but the resultant fusion is still a little-discussed milestone in American animation when it comes to Japanese influence and input in that artistic realm. While there had been a variety of dubbed cartoons from Japan that had made it to American TV over the prior twenty years, The Hobbit‘s lusher visions were the most notable yet. If the conventions of Japanese animation were still unfamiliar to an audience mostly conditioned by the lingering impact of Walt Disney’s breakthrough work, there was a distinct feeling all its own regardless. There’s also a sense of faded watercolour at many points throughout which seems to suit the story, telling of an older time.

No lie, that’s a really nice Bag-End. Image via The Lifestream

As an adaptation of Tolkien’s original Hobbit, meanwhile, the script wasn’t perfect, with a few key sequences either shortened or omitted. Yet it turned out to be surprisingly faithful in many ways, down to the inclusion of numerous songs, either sung by onscreen characters or by performers on the soundtrack, with lyrics taken directly from Tolkien’s own poems. The basic arc of the story remains the same – the comfortable Bilbo Baggins is swept up in an adventure regarding stolen dwarven gold, meets and/or escapes from trolls, elves, giant eagles, orcs and especially a mysterious creature named Gollum while at the same time gaining a magic ring, and along with his companions faces a terrible dragon and what happens after said dragon’s death. A little sharper cynicism and tragedy is introduced towards the end – where in the book three of Bilbo’s dwarf companions die, seven die in this version – and there’s even a Middle-earth riff on the supposed W.C. Fields chestnut ‘On the whole, I’d rather be in Philadelphia’ introduced near the end. Otherwise it’s a often effective, compact presentation of a classic children’s book story in a different medium.

In perhaps the most notable change from whatever Tolkien’s original preference might have been when it came to any adaptation, nearly all the characters are portrayed by American actors, using their own natural accents. (An elegant exception: Australian actor Cyril Ritchard, in one of his last performances, as Elrond.) It’s a quietly winning ensemble presentation in ways, starting with Orson Bean’s genteel but never cloying Bilbo, delivering the key moment in his story – facing down his own fears before confronting the dragon Smaug – with understated dramatic heft. John Huston’s inimitable voice perfectly suits Gandalf, Richard Boone amps up a vicious, contemptuous sneer for Smaug, Hans Conreid invests Thorin with both command and a little conniving and, in a tour de force, the German-born verbal surrealist Brother Theodore voices Gollum with all the self-pity, anger, and calculation that could be asked for, his low grumbles one heck of an introduction to what remains Tolkien’s most compelling character.

Rankin/Bass’s The Hobbit was widely watched, received a few awards and nominations, and generally served as a good way for the curious to get a sense of what Tolkien’s creative vision could encompass. Meantime, Ralph Bakshi was already hard at work on his own Middle-earth sojourn. After he’d built up his animation credits working for other houses as well as establishing his own production company during the 1960s, Bakshi had his own breakout with the release of Fritz The Cat in 1972, an adaptation of one of Robert Crumb’s characters from his own underground comic sensations. Profane, raunchy, more than a little offensive then and rather more so now, and definitely not a Disney lookalike, it made perfect sense in the then-current film milieu ranging from Deep Throat to Pink Flamingos, a garish thumbing of the nose. Various other films followed in said general vein, but 1976’s Wizards took a turn towards the cosmically pulp, a tale of a post-apocalyptic future Earth that also perfectly suited its time, the just-pre-Star Wars era of science fiction and fantasy across the board.

‘I just want to place a drive-through order, dammit!’ Image via the OC Register

It also turned out to be a handy proof of concept that Bakshi and his team could handle that kind of ‘big’ story, in the same way that his previous (though at that time unreleased) effort, Hey Good Lookin’, showed that he had an eye for combining classic animation with heavy use of rotoscoping, the process by which live-action sequences were drawn over to create animated end results. By the end of 1976 he was picking up after the previously mentioned John Boorman effort to film The Lord Of The Rings, describing his impulse in a 2006 interview to try and ‘save’ Tolkien’s work from a Hollywood process the author had always been skeptical of. He then set about what was planned as a two-film project for United Artists, backed by producer and partial Tolkien rights holder Saul Zaentz. Peter Beagle, a noted Tolkien appreciator who was a fantasy author in his own right, was brought on board to help massage an earlier script version for the first of the two films, while a variety of live action shoots were scheduled in Spain. Bakshi felt, not unreasonably, that this would be the easiest way to capture large battle sequences in particular. In the end a large portion of the film consisted of a blend of animation, rotoscoping and solarising, the latter being a tone-reversal effect that can be achieved with photography. The first film came together in time for that holiday 1978 season as indicated, but with a major caveat – United Artists, over Bakshi’s strenuous objections, released the film without indicating it was the first of two planned parts.

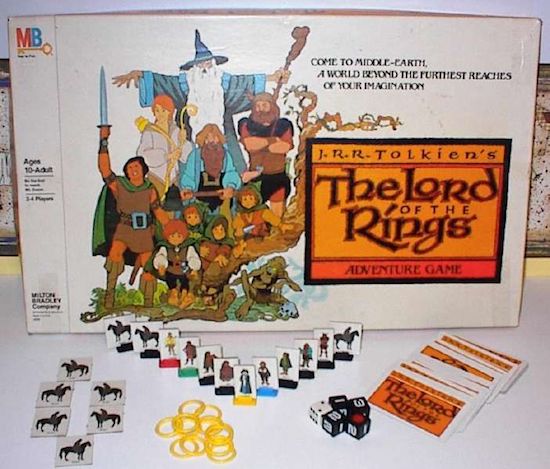

At this point it’s worth stepping into my experiences as a seven-year-old kid towards the end of 1978. I’d seen the Rankin/Bass Hobbit and, thanks to both a version of the original book featuring stills and concept art from the production and a complete start-to-stop double vinyl soundtrack album, had grown familiar with the overall story more and more. I wasn’t quite aware of The Lord Of The Rings, though I definitely had grown to recognize Tolkien’s name, or more accurately the then-to-me seemingly strange and mysterious ‘J. R. R. Tolkien,’ as his name always appeared. I’d had my mind blown away by Star Wars the year before, and bit by bit I was also getting slightly more aware of these things called science fiction and fantasy to begin with. It would take a couple more years before I was fully on board, but I do remember print stories and photos about Bakshi’s The Lord Of The Rings in various kids’ magazines, a board game, other ephemera floating around. But I didn’t see it then, and wouldn’t for a few more years. It was more like something that had happened, but hadn’t quite stuck beyond a fleeting moment.

Let me guess what you’re supposed to do. Image via Tolkien Boardgames.

Viewing Bakshi’s The Lord Of The Rings now, with all the knowledge of the compromises that shouldn’t have been pushed for, as well as the inevitably of-its-time technical reach and resources available to him at that moment, makes for a strange, imperfect experience at the least. It is of course blatantly unfair to hold it to the standards of Jackson’s films on that technical level even beyond the basic animation/live action split. While the distance between the filming of the two was barely two decades, the sheer leaps in effects presentation alone put each production on either side of a stark divide. Taken as is, Bakshi’s film is a strange, hybrid beast, often simultaneously gripping and head-spinning, with aesthetic and design decisions that almost effortlessly range from the striking to the utterly laughable. The acting choices vary wildly in turn, and the whole film ends on an enforced note of bizarre irresolution thanks to it not being offered as a clear first half of a larger whole. Yet for all that, the film is still a strangely affecting watch – nowhere near as unified and focused as the Rankin/Bass Hobbit, but inhabiting its own unsettling, sometimes lurid zone.

In terms of the major beats of the story, the core points are there in Beagle’s revised script and Bakshi’s filming of same. Like Jackson, Bakshi excises the Tom Bombadil sequence entirely, and similarly Bakshi creates a prologue to summarise necessary backstory at the start, from the forging of the One Ring to the encounter of Gollum and Bilbo. From there we get Bilbo’s disappearance, Gandalf telling Frodo about the Ring, Frodo, Sam and unexpected fellow travellers Merry and Pippin making their way to Bree, meeting Aragorn, and so forth. There’s a dramatic confrontation with the Nazgul, a race to Rivendell, the council and creation of the Fellowship, a journey through Moria, Gandalf’s fall, I could go on easily enough. (A major exception: Frodo and Sam’s encounter with Faramir is completely absent.) The film gets up to the point where the Battle of Helm’s Deep has been won and Frodo and Sam are about to enter Mordor, led unwittingly by Gollum towards Shelob – in essence, where the second of Jackson’s films ended as well.

Also, Saruman the White is now Saruman the Red for some reason. And half the time is called Aruman. There are…flaws in this film. Image via LOTR Wikia.

That fact right there is the first tell that Bakshi had some truly unavoidable problems when creating his film from the original novel. His Lord Of The Rings reached 133 minutes. Jackson, admittedly able to create three films instead of a planned two, hit 178 minutes with his first film alone, then that amount again with the second one – six hours versus two hours fifteen minutes (and that doesn’t even count what Jackson’s further director’s cuts included). Regardless of how one felt Jackson handled the material, he had the space to explore a lot more of it, and a lot more of the characters, than Bakshi did.

This wasn’t an unavoidable situation – plenty of lengthy novels have turned into compact enough films with adaptations that drew on the core work and then focused further. But whether it was Beagle, Bakshi or some wider combination at fault, the resultant screenplay as filmed feels incredibly disjointed. Conversational interactions often have odd pauses or random resolutions, with an omniscient narrator, the same from the prologue, occasionally interjecting to fill in some gaps, often with explanations that don’t entirely hang together. This choppiness is exacerbated by the fact that some material only makes full sense to someone who has already read the book, being too rapidly explained away or glossed over for a viewer that’s coming in totally cold to the story. It’s not completely impossible to follow along, but it’s all too easy to imagine someone going, ‘Okay… where are we again? What’s happening here?’

A good example can be seen with Treebeard’s brief appearance towards the end of the film. Aside from a voiceover part that initially scares Merry and Pippin, all we see is Treebeard carrying the hobbits in his arms and exchanging a bit of dialogue. And that’s it – no sense outside of the vaguest of who or what the character is supposed to be, where any of the characters exactly are, none of the tension (admittedly inflated in the Jackson version) about whether or not Treebeard will fight against Saruman or even if Treebeard is anything more than a vaguely odd character with a stiff walk. It’s entirely possible his role would have been more fully justified with the planned second film, but as it stands it’s just a minimal cameo, as opposed to the crucial role he serves as both rescuer and as foil to Merry and Pippin in Jackson’s adaptation. Here at least one can know that Merry and Pippin are safe, but that’s about it.

When it comes to the voice casting, Bakshi arguably made a more appropriate artistic choice than Rankin/Bass by going for British rather than American actors. Beyond that, though, it gets a bit uneven. John Hurt was the most famous name at the time, and his Aragorn has a certain gravitas, though the script sends him through some quick tonal shifts, from gruffly humorous to near-contemptuous. A retrospectively intriguing choice was Anthony Daniels – then coming off his unplanned smash hit star status as C3PO the previous year – as Legolas, though he lands somewhat flatly outside of a line-reading or two. There’s a fair amount of notable figures from UK TV and stage throughout, including Andre Morell in a brief, reasonably authoritative turn as Elrond, Michael Deacon with a few declamatory lines as Theoden and Norman Bird doing an amusing enough turn as Bilbo.

But the hobbit actors are pleasant at best without being gripping, and while Christopher Guard’s Frodo is steady enough, Michael Scholes’s Sam perfectly justifies Sean Astin’s previously recounted fears, playing his character as initially quaveringly clownish, then settling into a random dorkiness. Having one of the two key partnerships of the book undercut this way is bad enough, but when it comes to Frodo and Gandalf, William Squire has a strong enough voice for the wizard that gets lost in stagey delivery, oodles of exposition and a sense of superiority rather than empathy. Compared to John Huston in the Rankin/Bass Hobbit, able to convey both easy warmth and clarity when the moment demanded it, it’s a terrible choice. Yet for all that, there are two strong performances of note in the cast are worth talking about in more detail later in this piece.

‘Look I know I mostly shout at you but it’s in the contract.‘ ‘Whuh?‘ Image via cornel1801.

Script and acting are one thing but Bakshi had also made his name for the work he and his team had done on design and animation, and together combined that was the remaining key factor an adaptation had to deliver. If the script was often rushed and choppy and the acting was on average serviceable, the actual look of the film could have still resulted in something more memorable in the end. Given when the film was made, it would have been perfectly understandable if he’d gone with such noted fantasy illustrators as Boris Vallejo and Frank Frazetta. Indeed, Bakshi’s follow-up film to Lord Of The Rings, another fantasy epic called Fire And Ice, was done with Frazetta’s extensive participation on a number of fronts. Here, Bakshi drew instead on the classic work of American adventure and fantasy illustrators Howard Pyle and N. C. Wyeth, combined with his long open love of melodramatic colours and a distinctly trippy, post-psychedelic melange of design and visual elements, as well as, as noted earlier, the extensive rotoscoping and solarising of live action footage.

To say whether or not it all succeeded is almost besides the point – it is, if nothing else, absolutely distinct, somewhere between a collage of many different striking approaches and a chaotic ‘throw everything against the wall and see what sticks’ all-out effort. Perhaps the most notable element throughout is whenever rotoscoped hero characters, in the space of a scene or an edit, turn into solarised/colourised live action elements featuring either the original actors in costume or their appropriately attired and bewigged stand-ins (notably for the hobbit characters, with famed actors like Billy Barty and Felix Silla doing the honours). It’s not constant by any means but it happens often enough later in the film to be a little jarring at best, though the film is generally consistent with the colouring of costumes and looks.

Hi, I’m a guy. Really, I’m a guy. Image via Animated Movie Guide.

Meantime, when it comes to the larger battle scenes later in the story, it’s almost all solarised live action, with blonde-bewigged riders of Rohan and hordes of Saruman’s orcs facing off in not-always-well-staged battle scenes (there’s often a lot of sword-waving and tentative stabbing). The live action orcs wear any number of definitely inhuman masks, with animated red eyes to produce a combined effect that’s unsettling enough, but sometimes the masks aren’t so much frightening as goofy.

When fully animated, the lead characters are a bit of a mix design-wise. It’s almost impossible to do Gandalf incorrectly when his appearance is so clearly established by Tolkien, and it’s one of Bakshi’s best efforts. The general appearance of the Fellowship is effective enough – one to-be-discussed exception aside – though Aragorn is saddled with a strange brown short tunic that seems improbable for hard living on the road. His overall look is craggy and rough, which more readily suits the character given his backstory, though many fans still found it hard to square him with their preferred mental picture of the character. Legolas and Gimli’s looks are generally fine – the latter often seems more like a tired auto mechanic with a long beard than anything else, perhaps – while the hobbits’ looks are defined by huge mops of hair and, as previously noted in Sam’s case, a ridiculously big nose, goofy smile and generally everything else that caused Astin’s hackles to rise.

Instead of realism, in line with Tolkien’s own belief in Middle-earth as simply being an older version of our actual world, the overall appearance of locations and landscapes tends towards the deeply fantastical. The prologue aside, created as a filmed in silhouette presentation not all that far off from classical shadow puppet theatre, we first see Middle-earth via the Shire, and it’s warm and bucolic enough. But nearly everything else after that tends towards extremes, whether it’s Saruman’s tower Isengard, a jagged edifice under brooding skies, Elrond’s base of Rivendell as a strange, not quite normal structure, the murky caverns of Moria, sometimes with bizarre elements such as monstrous skulls in the background, or the dreamland of Lorien, trees mixed with strange lights in shadows. Even ‘normal’ locations like the plains of Rohan or on the Anduin are suffused in odd colours, unusual skies.

Bakshi’s most striking designs perhaps unsurprisingly come courtesy of portraying the darker sides of Middle-earth, and his Ringwraiths, per Astin’s comment, for many remain the strongest points of the film, with odd, strangled voices and screams matched with the heaps of dark clothes that define the characters. The glowing red eyes Bakshi adds to the unseen faces underneath all the layers are a bit of a stretch from the book – Tolkien didn’t indicate anything like that was the case for them until much later in The Return Of The King – but still works well enough in its own right. Bakshi’s Balrog is undeniably weird, a strange combination of lion and butterfly-man thing, but it’s absolutely unique in turn, and when fully animated the many orcs, with their own red eyes and jagged yellow teeth, make for vile enough antagonists.

It should also be noted at this point that there’s one egregiously bad element that was wholly out of Bakshi’s hands – the score. Bakshi was thinking of rock bands like Led Zeppelin getting involved, given their own overt Tolkien nods in their career, and it would be intriguing to imagine Jimmy Page getting his folk jones on with an accompanying soundtrack. (Rankin/Bass’s Hobbit soundtrack got in an actual folkie, Glenn Yarbrough, for the sturdily-sung theme song, and Maury Laws’s score was a nice mix of standard orchestral approaches and some engagingly mysterious arrangements.) Countering Bakshi, producer Saul Zaentz wanted something he could release on his own record label, Fantasy, and drafted in veteran Hollywood composer Leonard Rosenman. The fairest thing to say is that, despite some notable credits over the years, Rosenman was definitely no Howard Shore in this field. Putting it more tartly: it’s an abomination, either strident or sappy, and only one or two strange or discordant moments to give it any distinctness; comparing it to John Williams’s amazing contemporaneous syntheses of classical impulses on Star Wars, Close Encounters Of The Third Kind and Superman is an insult to Williams. The first thing anyone sees of the film is some brief opening credits and Rosenman’s utterly bombastic and horrible main theme blasting in, and I wouldn’t be surprised if any number of viewers on that opening run mentally checked out as soon as they heard that. (The score got a ‘special vinyl rerelease’ or something similar a few years back, and I can think of no greater indictment of the uselessness and resource squandering of modern vinyl culture than that particular release.)

Ultimately, Bakshi’s effort was exactly that – Bakshi’s rather than Tolkien’s vision, which is of course the process of any adaptation, though one that at least made an effort to honour the source. There’s enough going on throughout that one can easily imagine what an original story along these lines, not burdened with having to cram a huge book into a short space, with plot points and set pieces taking the understandable lead, would have been like. It’s by no means a total jettisoning of Tolkien, and the complexities of the author’s world – where narrators aren’t fully omniscient, and the internal workings out of a number of characters are never portrayed – simply aren’t going to be suited for a visual dramatisation anyway. This much is also clear in Jackson’s own later adaptations. But Bakshi’s Lord Of The Rings is a singularly mixed product, at once almost on its own in terms of mass-market animation of the time and place, distinct for that reason, yet not fully clicking as a film or narrative either. Audiences were left hanging by the abrupt ending with no indication it was supposed to be a first of two parts, aside of what clearly was a bit of rushed voiceover saying it was the end of ‘the first great tale’. While the film readily made back its budget and more, Bakshi was burnt out with studio interference and, by his own accounting later, realised he ultimately preferred creating his own narratives.

As well as animating Rolling Stones videos. Hey, it’s work. Image via Cinema Cats

The longer legacy of Bakshi’s Lord Of The Rings is perhaps not dissimilar to David Lynch’s Dune – a distinct director with strong visual sense and general interests interpreting a widely read, sprawling epic in an (alternately) fantasy or science fiction setting, struggling with how best to fit the scope into a end product meeting commercial requirements of the film’s backers, and ultimately releasing a film to mixed success at most. Both Bakshi and Lynch have created enough work that they can look back on what both went through as learning experiences and reminders of what they wanted to avoid doing in the future, with the key difference being that while Lynch has remained at best ambivalent about his Dune work, Bakshi is still proud of his own attempt at Tolkien if not fully satisfied with the ultimate end result, regularly sharing images from the film online.

Although c’mon, why WOULDN’T Lynch be proud of this one Dune shot that’s more disturbing than all of Twin Peaks? Image via Barnes & Noble

But in the immediate wake of Bakshi’s film, three very different efforts ended up completing what could be termed the then-current cycle of Tolkien adaptations. First out of the gate was, ultimately, the least – a 1979 American radio production of LOTR, broadcast on the NPR network of stations. The golden age of American radio plays had long passed, though NPR, the closest thing to BBC’s radio services this country had and has, was trying to keep the flame alive. (A notable effort that soon followed: a widely enjoyed radio adaptation of Star Wars, which led further to all three of the original films getting such treatment.) UK expatriate broadcaster, educator and activist Bernard Mayes, a strong supporter of public broadcasting based on his previous BBC experience, adapted Tolkien’s work as one of a series of similar efforts he did for NPR over the years, including classic Greek tragedies and works by Dickens. Unlike Bakshi he didn’t have to worry about cutting the story in half, so anyone left unsatisfied by United Artists’s handling of that factor got a version of the full tale here instead. The resultant effort was a nearly twelve-hour effort across twenty-four half hour episodes, even including the oft-excised Tom Bombadil sequence. Mayes himself played that character as well as a reasonably curmudgeonly Gandalf.

But did it work? In a word, no. In fact, it’s mostly awful. No question that Mayes knew his literature but he seems to have thought of The Lord Of The Rings strictly as a child’s tale. Perhaps understandable but if Tolkien had ever heard the end results, that might have killed him instead. The rest of the ensemble was mostly drawn from local Washington DC actors, and while their enthusiasm can’t be faulted, the performances are mediocre at best, and sometimes notably bad. In one of the strangest decisions, all the hobbit characters aside from Frodo are voiced almost as children, while various elf characters have ridiculously squeaky tones. (The in-context, even more bizarre exception is Elrond, who is voiced like a bloated broken down Santa Claus for no good reason whatsoever.) James Arrington’s Frodo is unremarkably passing, but his Saruman is a rough voiced disaster, and things get worse from there. Meanwhile, the inclusion of the Tom Bombadil sequence, however enjoyable in context for completists, was balanced by huge excisions of sequences later on in the story, rushing to a quick conclusion. Sonically it was no treat either, relying on various stock sound effects and musical cues, including an uncredited overuse of Erik Satie’s Trois Gymnopédies theme.

The following year Mayes oversaw a similar adaptation of The Hobbit that was comparatively more successful. Whether the story was just easier to readily adapt, or Mayes found it more to his taste, one can’t say, but many of the same actors reappeared in the same roles or took on new ones and seemed to have a better grip on the experience. It’s not truly remarkable, suffering from the same technical limitations as the other production Mayes and his team did, and Rankin/Bass’s production, while not as complete, remains the best direct adaptation of that book still from that period. But both of the Mayes radio adaptations retained a certain popularity in later years after being repackaged for sale in elegant wooden boxes in both cassette and later CD versions. That’s about all that is notable about them in the end, though, and it’s better to think of this as a blip on Mayes’s own long and quite unique career in general.

Not whether they’re GOOD actors, but there is a full cast of them. Image via Contains Moderate Peril.

1980 also brought probably the most unusual effort – a new Rankin/Bass production. At the time of The Hobbit‘s broadcast there had been plans of some sort of sequel, with the bland working title of Frodo, The Hobbit II, though given the tangle of exact rights who knows how that would have exactly played out. With Bakshi’s Lord Of The Rings leaving the story hanging, and while the sequel’s production wasn’t directly tied in with Bakshi’s effort at all, Rankin/Bass ended up doing the still strange but almost logical thing of, essentially, finishing Bakshi’s work for him, but doing so with the cast, animation style and general approach of their own Hobbit. The result was The Return Of The King, and as choppy and odd as Bakshi’s reduction of the larger story was, even that was nothing compared to what Rankin/Bass did here.

On a technical level, the approach was directly similar to their Hobbit work, with Topcraft again providing animation based on Rankin’s designs, Romeo Muller writing the script, often using a number of lines directly from the book, and Maury Laws providing the music. Glenn Yarbrough returned as well, this time as a direct character, an otherwise nameless minstrel, with songs recurring throughout the presentation, in combination with John Huston’s Gandalf in voiceover, to create an overall narration as needed. Orson Bean again played Bilbo, as well as playing Frodo, and Brother Theodore returned to do his compelling version of Gollum, while various voice acting legends like Paul Frees and Don Messick again took on a number of roles and the newly-arrived Roddy McDowall assayed Sam. (Another new member of the ensemble: voice actor and Top 40 countdown DJ Casey Kasem as Merry, and when you hear the voice of Shaggy going ‘HEAR ME O DARKNESS, I WILL AVENGE MY LORD!’ at one point, you’ll question a fair amount of reality.)

However, the problem with the adaptation was pretty much built into its circumstances. Whether directly prompted by what Bakshi was able to do or not, Rankin/Bass concentrated on, indeed, the final book in the Lord Of The Rings cycle. Using a post-Ring-destruction birthday party for Bilbo as a framing device, they essentially set out to tell, in only about ninety minutes, everything that happened in that book. It’s a similarly crammed down situation as Bakshi faced, and to say that the story was reduced dramatically is an understatement. Most importantly, if again however unintentionally, Bakshi’s film and this production don’t ‘join up,’ so between the two films the story leaps on the one hand from the Battle of Helm’s Deep to an already-in-progress siege of Minas Tirith, and on the other from Frodo and Sam approaching Mordor with Gollum to Sam breaking into the tower of Cirith Ungol to rescue Frodo. (Worth noting as an aside: this means that one of the most memorable passages of both the book and of Jackson’s adaptation, Shelob’s actual stalking and attack on Frodo and Sam, wasn’t animated by either Bakshi or Rankin/Bass at all during this time.)

From there the story both rushes along – in Minas Tirith, Denethor, reasonably well played by American TV star William Conrad if somewhat strangely designed otherwise, is quickly introduced and almost as quickly dies – and then starts slowing down entirely, almost bizarrely. One early example can be seen with what happened to a dramatic moment in the original text when Sam, having rescued the Ring following Frodo’s capture after Shelob’s attack, is tempted to claim it for his own for a brief moment. It’s a striking illustration by Tolkien of the plasticity of the Ring scaled for the wildest dreams of whoever holds it: Sam considers the idea of becoming a bold warrior, ‘Samwise The Strong,’ conquering Sauron and Mordor and turning it into a garden, before rejecting it as, essentially, the power fantasy it is.

Striking as it is, however, in the adaptation context of a pretty busy narrative and a short period of time, it’s hard to fully justify including it; it’s an illustrative pause at most. But Rankin/Bass turn it into a big production number, with McDowall turning on the acting jets, the design portraying Sam staring off into the middle distance, Yarbrough as minstrel singing about the situation. It also includes a full-on daydream sequence with various mounted animated warriors shouting ‘Hail Samwise The Strong!,’ a charge on Sauron’s tower, the depiction of the garden coming to Mordor and so forth. It’s not badly done in its very melodramatic way, but it’s still a cul de sac at most.

In a way it also illustrates what the potential limitations are for the Rankin/Bass approach here as a whole. Their Hobbit handled small or intimate situations pretty well – Bilbo and Gollum’s wary facing-off, fighting off bands of orcs or giant spiders, even Bilbo and Smaug’s confrontation – with only the final battle at the end a significant upscaling of action, and even that was handled quickly enough. Tonally as well, they were well suited to The Hobbit‘s generally lower-stakes story all around, a little more of the classic fairy tale than the sweeping epic. Bakshi’s own dramatic take on what Tolkien had done with The Lord Of The Rings – a sequel to The Hobbit that took on life of its own – was, if not fully successful, still appropriate for the scale at many times, with its vivid colors, grim situations and sense of real scope. In the context of that film, The Return Of The King feels like what it, however unplanned, is – a made-for-TV continuation of a big movie theatre story, a contrast made all the more noticeable due to the previously mentioned lack of artistic, script, acting or any other continuity between one production and the other.

Other more straightforward adaptation problems crop up – Merry and Pippin barely figure into the story, Legolas and Gimli are completely absent, Aragorn doesn’t appear at all except towards the end. But the most notorious change happens during Frodo and Sam’s journey across Mordor to Mount Doom, during the key moment when they are surprised by Orcs and, taken to be deserters, are forced to join a company of them on a march. It should be noted here that in The Hobbit, the various songs performed were never shown performed on screen by any characters, and as noted all were drawn directly from songs or poems in the original book. No such luck here: while the twisted proverb ‘When there’s a whip, there’s a way’ is spoken by a sadistic Orc captain in the book, there most certainly was not a funk-rock song of that title that all the orcs sing along to as they march, with lines like ‘We don’t want to go to war today/ But the lord of the lash says nay, nay, naaaaay!’ (One would be forgiven for imagining if Casey Kasem as Merry then stepped in and said, ‘And at number 39 on the Mordor charts…’)

Still, for all this, I have to give Rankin/Bass’s The Return Of The King this much when it came to that initial broadcast in 1980 when I was nine years old. Having still not seen Bakshi’s film, but having by that point reread The Hobbit a number of times and with that soundtrack album in hand, I was primed and familiar enough with Rankin/Bass’s take on that story that seeing The Return Of The King wasn’t entirely weird or strange in terms of its look and voice talent. And – speaking frankly – since I didn’t know the whole background of the story, I didn’t know what I was missing from it and… I didn’t miss it. Strange but true, and arguably a strong point in its favour. Not having yet read The Lord Of The Rings, not having seen the Bakshi film, I took The Return Of The King as it was. It came across as a self-contained story that, thanks to John Huston’s narrative comment early on that ‘many adventures’ had already happened beforehand, had some background, sure, but nothing crucial I needed to follow along here. Which sounds utterly crazy in just about any other context, I know – but I was fine with it here. I ended up being more familiar with the (single album, in this case) soundtrack that came out soon after, and ultimately didn’t finally read The Lord Of The Rings itself until the end of 1983, when I was twelve. After that, of course, I realised in retrospect that I had essentially spoiled myself for a lot beforehand. But you have to start somewhere.

It was only years later I learned about one last adaptation from the time, though, having in those later years taken the plunge into the full Tolkien interest – or if you like obsession – I have to the present day. (Yes, I bought The Fall of Gondolin earlier this year – without regret.) In 1981, Brian Sibley, having already had a number of BBC radio drama scripts under his belt, began his notable 1980s run in producing fantasy adaptations for Radio 4 with a full adaptation of The Lord Of The Rings. Co-written with Michael Bakewell, and co-directed by Jane Morgan and Penny Leicester, Sibley’s The Lord Of The Rings is, of all the adaptations of that book from the time, the absolute standout. It’s very much an old school effort in many ways – numerous veteran actors deliver their lines with the kind of brio where you can sense the appropriate dramatic gesture without actually seeing anything – but it’s also magisterial in the best sense. It’s the closest to the original book by far as well (though again doing the dramatically correct move of dropping the Tom Bombadil sequence), and at thirteen hours not only beats out the American radio version by an hour but uses its time much more intelligently for a better paced story.

‘But I’m so cheery! Hey dol ring dol-’ ‘Thank you, NEXT.’ Image via Wikia.

Sibley and Bakewell cleverly and carefully weave in material to flesh out the start of the main story, beginning, after a short narrator-read prologue, not where the book does with Bilbo’s plans for his birthday party, but with Gollum skulking on the borders of Mordor, captured by a sentry. This and similar moments that follow throughout never appeared in the main text but cropped up in its appendices, as well as other posthumous Tolkien publications like Unfinished Tales. In using them Sibley and Bakewell create some solid dramatic tension for their medium, as well as cleverly throwing off expectations by anyone who already knew the story cold. Careful nods to deeper Tolkien lore were added as well here and there, but nothing too distracting, just a nice easter egg or two for the hardcore fan.

On a technical level, the last great veteran of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, Elizabeth Parker, then only a couple of years into her efforts there, handled effects and atmosphere with inspired detail throughout. Musically, orchestral and opera composer Stephen Oliver created one of the best efforts in his tragically foreshortened life. He carefully showed a flair for key character themes in much the same way Howard Shore would later do for Jackson, also creating fine arrangements for a number of Tolkien’s poems and songs throughout. Oliver’s main theme, a stately string-led performance, is almost 180 degrees from Rosenman’s horrific equivalent for Bakshi and is all the better for it.

On the acting front, Gerard Murphy was an engaging, understated but clear voice as narrator throughout, a good anchor for what is a complicated story in any version. Ian Holm, already fifty years old and thoroughly established, did a truly wonderful job in the lead as Frodo, capturing a bright, engaged youthful feeling at the start that inevitably transformed into the voice of a quietly haunted, unsettled man at the end. There’s a dramatic moment towards the end of the adaptation where Frodo, overwhelmed, angry and utterly crushed at how the Ring has caused him to turn on Sam, rages in weeping despair, and Holm delivers it so well I still get chills. Michael Hordern also gets a pride of place among the veteran performers with his version of Gandalf; if he sounds stuffier than John Huston’s version, and was later fully overshadowed in the public eye by Ian McKellen’s pitch-perfect take, Hordern’s distinct voice, good ear for the right tone at the right time, and easily shifting blend between seriousness and careful humor suits the production excellently. Robert Stephens is the remaining key veteran lead, informing with Aragorn with wry but not brusque humor, a controlled intensity at crucial moments and a good sense of charisma. Other notable figures who’d long since made a name include Peter Vaughan as a slowly crumbling Denethor, Peter Howell as a seductive and angry Saruman, and, in a pleasure of a performance, John Le Mesurier as a warm but regret-tinged Bilbo.

There’s a real surprise of a delight in one absolutely key role from a comparatively younger actor, though, who was just on the start of what remains one of the standout careers to the present – Bill Nighy. Credited more formally here as William Nighy, he assays Sam in a fashion utterly unlike the regrettably cloddish take in Bakshi’s film, as well as Roddy McDowall’s often declamatory take for Rankin/Bass and Lou Bliss’s cloyingly earnest version for the American radio production. Nighy convincingly portrays a different earnestness here, that of a nervous young man who admittedly dreams big at points, swept up in a story he doesn’t fully understand but which he resolves to see through. It’s the story of Sam as written in the book in the first place, and Nighy is of all the previously mentioned performers the one who actually gets Sam right, never goofy or comic relief, just sometimes awkward, stubborn and once or twice unsure until he finds his core strength. Honestly, after talking about all the other versions of Sam here, just being able to think about Nighy’s feels like a real relief.

There are two other performances, though, that also deserve mention which I’ve hinted at earlier – and which provide one last surprising connection to Bakshi’s work. As mentioned, Bakshi’s great gift in his casting was to go for British actors to begin with, even though the end results were at times uneven. But two of his choices were so strong, and the performances good even in their context, that the actors were cast to redo the same characters all over again in the BBC version. The end result in both cases could almost only be compared what Ryan Reynolds did with Deadpool – an initial appearance that was definitely compromised to say the least, followed by a later version with a different director and approach that turned out to be completely spot on and a success in its own right.

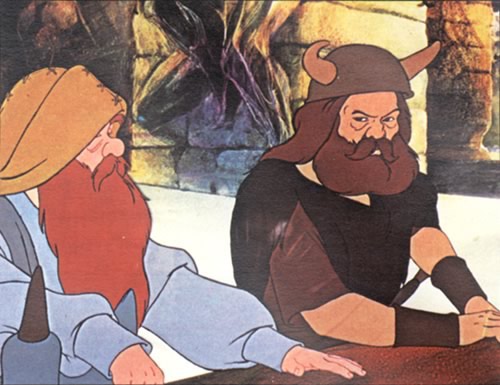

Of the two actors, Michael Graham Cox is the one who had to do the most unintentional bootstrapping thanks to how his character, the flawed and ultimately doomed Boromir, was portrayed in Bakshi’s film. In what was probably his worst overall design decision for an individual character, Bakshi created Boromir, essentially a prince of men from an ancient land obsessed with heritage and history, as a fur-laden Viking barbarian – even including a horned helmet to boot. It would have worked perfectly in either Bakshi’s Wizards or Fire And Ice; in his Lord Of The Rings, the character, barely given any introduction or context, seriously looks like he’s wandered into the wrong animated film. (The deeper irony is that same year Cox was served much better on another famous animated film, as the intense warrior Bigwig in Watership Down.)

‘Uhhhh…’ ‘I SAID I come from the land of the ice and snow, got a problem with that?’ Image via Council of Elrond

That said, Cox does his best with what’s given to him, and while Boromir rather is rather extravagantly overacted at points in terms of animation, Cox hits the melodrama just enough without succumbing to it. In the BBC production, Cox is given much more room to breathe, his doubts and increasing darkness emerging in the script more naturally as in the book, and he delivers the all important confrontation scene with Holm’s Frodo and the subsequent farewell scene with Stephens’ Aragorn quite well.

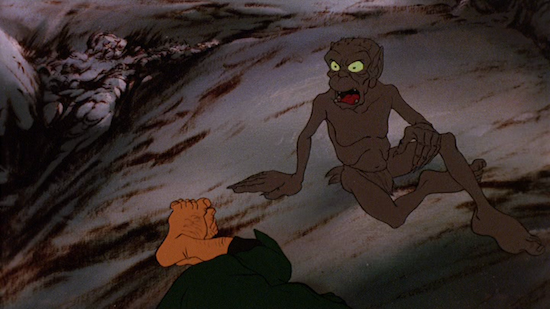

But it’s Peter Woodthorpe who is able to get the second chance of a lifetime when he returned to Gollum for the BBC production. In Bakshi’s film, Gollum’s design is pretty sharp, a strange alien creature that’s just human, or rather hobbit, enough – a noted difference from the Rankin/Bass version, essentially that of a humanoid frog. But the trick with Gollum, as performers from Brother Theodore to Andy Serkis have discovered, is in how you perform his speech, translating the self-obsessed, circular dialogue of that damaged figure into a convincing performance. Again, much like Cox, Woodthorpe does a solid job in the short scenes he has, a few sequences in the second half of the film, though nothing is quite so dramatic after his introduction when he stalks and then is captured by Frodo and Sam. His voice isn’t as darkly rumbling as Brother Theodore’s, but it’s a perfectly serviceable performance.

‘Look, I gotta be honest, but your feet stink.’ Image via The Big Picture.

The BBC version is another thing entirely. As noted, Woodthorpe’s literally the first voice one hears after Gerard Murphy’s initial narration, and while he’s had some grounding in the character by default, you get a sense here that he’s actually living it. It’s easy, almost too easy, to imagine the whines and self-conversation he has as just being the latest in an endless stream, a deeply-scarred soul unable to think or process any other way. Even just a few minutes in Woodthorpe’s given more to do as an actor than he had been in Bakshi’s film, culminating in a horrific sounding torture sequence where, utterly broken and only wanting to retreat inside his mind, Gollum’s deepest secrets are forced from him by Sauron’s creatures.

From there Woodthorpe is first the ghost that quietly haunts the story much like in the book – there’s an early flashback scene between Gollum and Bilbo, otherwise he disappears directly until he emerges, half-heard and murmuring, on the Fellowship’s path. This time the stalking of Frodo and Sam and his subsequent capture is even more dramatic, a standout moment occurring when an elf rope is tied to Gollum’s ankle, a sequence in the book that is shown to cause the Ring-scarred Gollum deep physical pain. Woodthorpe first almost screams silently, a wordless high-pitched whine that seems like something only a dog can hear in the thinnest of air, that suddenly descends into a roaring shriek, an absolutely near inhuman explosion of fear, anger and sorrow all at once, all wrapped up in total desperation. It’s unsettling to say the least, but it’s brilliantly done, and miles beyond his equivalent moment in Bakshi’s film.

The full dynamic between Woodthorpe, Nighy and Holm’s performances then plays out from there across the rest of the production until that dramatic end, Gollum falling in fear and terror into Mount Doom with the ring, and Woodthorpe doesn’t let up throughout. One can imagine the sheer toll it must have taken on his voice pretty easily – Serkis has always been vocal about what it did with his when working with Jackson – but that just makes the skill of Woodthorpe all the more admirable. Not entirely a villain, certainly no hero, Gollum is one hell of a character that deserves one hell of a performance, and Woodthorpe’s second try scores completely.

Yeah, that Rankin/Bass frog Gollum. Brother Theodore really does kill it vocally, though. Image via YouTube

So in a weird way, it could be that the greatest legacy of Bakshi’s Lord Of The Rings wasn’t so much the film itself as it was in terms of what directly resulted from it. Further, given how there was the follow-on connection where Ian Holm went from playing Frodo in the BBC version to Bilbo for Jackson’s films, there’s arguably a throughline via actors directly from Bakshi to Jackson as a result, another connection, if one that can’t be shown simply on the screen either way. Yet here’s the thing in the end – for all that it was one of numerous adaptations at the time, of varying success, aimed at different audiences, Bakshi’s The Lord Of The Rings was the one that aimed for the biggest scope, in what then was seen as the gold standard of popular entertainment – mass-market film – and did so carving out its own distinct, unusual niche. Sure, it may not have everyone happy by a long shot, and yes there are parts of it that can’t be anything but cringeworthy. But there are plenty of successful films – and successful books – that fit that description too. In the end, Bakshi’s effort deserves a little more sunshine that it’s gotten.