I was never a punk, and never even wanted to be one. To this day, my skin has never been pierced by anything sharper than a stone on a football pitch or broken glass on a bar floor. Growing up in the 70s and 80s, I never owned Never Mind The Bollocks – my favourite song by The Sex Pistols may even have been ‘Frigging In The Rigging’ – and, to be honest, the little I’d seen of Johnny Rotten had scared the parting out of my hair. The closest I came to the punk movement was when I emerged from Kensington High Street tube station to wander through the nearby covered market looking for affordable clothes free of an M&S label.

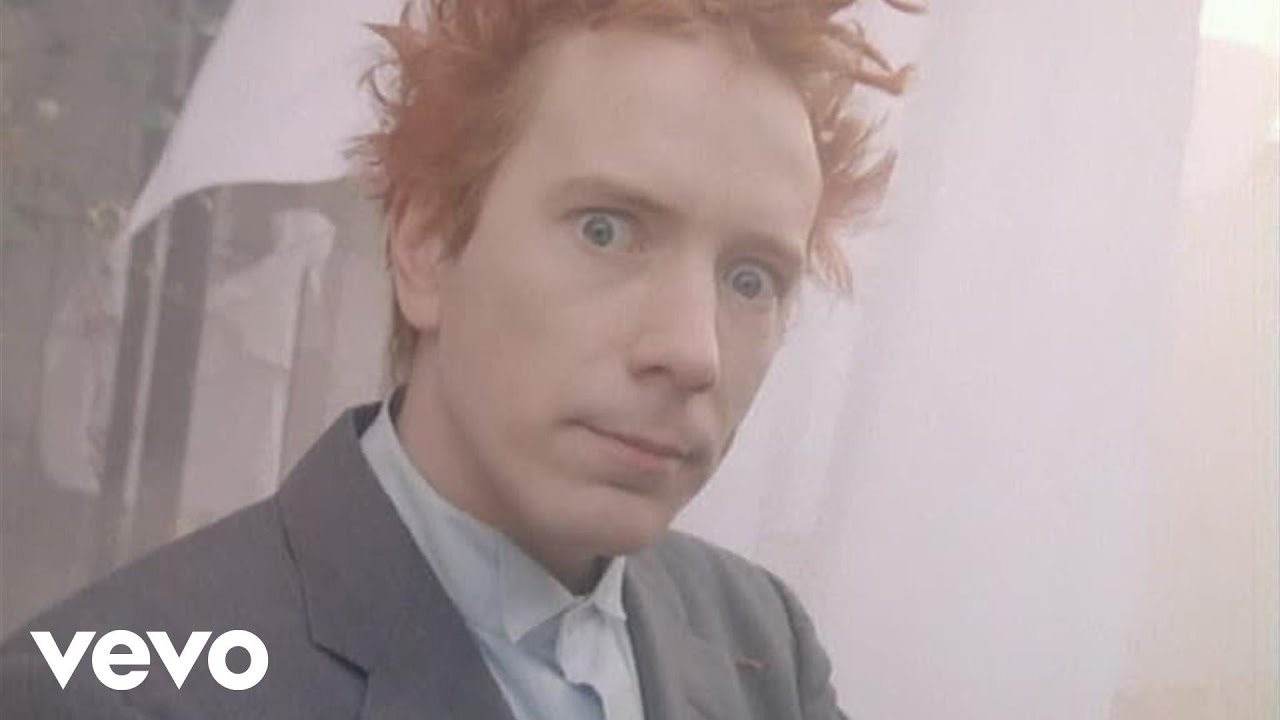

But when you’re young, lyrics are like horoscopes: you read into them what you want to find. And so it was with Public Image Ltd. whose 1986 single ‘Rise’ spoke to me in a manner I’d never before experienced. I knew it wasn’t really punk, but the memory of the controversy Lydon had caused only a few years earlier, disgusting my parents and conservative Britain in general, was a powerful reminder of what the man stood for: lawlessness and nihilism. These, until the moment ‘Rise’ rumbled first on the airwaves, were not qualities I’d sought in my life: I sang in the school choir, read George Eliot’s Middlemarch for pleasure, and watched cricket through the summer. But, as 1985 turned into 1986, around the same time as Michael Heseltine was forced to resign after butting heads one too many times with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, the song was everywhere, even taking former enfant terrible Lydon onto the front cover of Smash Hits. I, meanwhile, was bored and lonely, struggling to fit in amongst a group of boarding school pupils whose main ambition seemed to be to become worthy estate agents, powerful lawyers and wealthy city brokers. Lydon’s arrival in my life was immaculately timed.

In all honesty, I knew ‘Rise’ was about apartheid: Lydon told Smash Hits’ Tom Hibbert that, "I read this manual on South African interrogation techniques, and ‘Rise’ is quotes from some of the victims." The horrors of the country’s institutional racism were by now far from secret – even though Margaret Thatcher would still, a year later, refer to Nelson Mandela’s ANC as "a typical terrorist organisation" – and, in addition, I was about to join Amnesty International in protest. But what I heard was far more personal, and Lydon went on to admit that this freedom to interpret the words was deliberate: "I put (the quotes) together because I thought it fitted in aptly with my own feelings about daily existence."

Whether he intended them to express the feelings of an adolescent at one of Britain’s more renowned private schools is debatable, but so many of the words resonated with my life that it was way out of his control. Though those opening lines – "I could be wrong, I could be right" – first sounded like an admission of confusion coming from my mouth, from his they sounded like an accusatory threat that he in fact might be right on the money. Though the idea that "the written word is a lie" initially seemed like blasphemy to a juvenile Little Lord Fauntleroy immersed in academia, they opened my eyes to the fact that the books we were reading were not necessarily definitive. No one had ever "put a hot wire to my head / ‘Cos of the things I did and said", but I recalled powerfully my first night in the school chapel less than 18 months earlier, where we sat before our new headmaster as he informed us that the establishment’s goal was "to teach us the right habits for life". I felt that the school authorities, in their own way, wanted to make "these feelings go away", to turn me into a "model citizen in every way". I was hardly a victim of brutal, systematic, institutional racism, but I found in Lydon’s words the inspiration to question fundamentally what was going on around me, both in my immediate surroundings and the world at large. He’d articulated my frustration, and provided me with a foundation to continue: "Anger is an energy".

For many long-term fans up that point, Public Image Limited’s Album (or Cassette, or Compact Disc, depending upon the format you purchased) was the moment Lydon sold out once and for all. Even the cover represented a simple generic brand, an irony Lydon no doubt sought out. Less ‘Anarchy In The UK’, more ‘Profligacy In LA’ (where it was recorded), it saw Lydon unite with probably the most unlikely group of musicians in his career, gathered together by Bill Laswell, the producer behind Herbie Hancock’s 1983 album Future Shock, whose ‘Rockit’ single was arguably the first commercially successful track to feature scratching and led Laswell to further work with Sly & Robbie, The Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron. Laswell had also overseen ‘World Destruction’, Lydon’s collaboration with Afrika Bambaataa’s Time Zone a year earlier, but he was far from an obvious choice for Pil, even as they haemorrhaged fans on the back of 1984’s synth-and-horn-heavy This Is What You Want… This Is What You Get. His selection of players was star-studded, but it was an unlikely bunch of teammates, one guaranteed to alienate PiL fans: Miles Davis’ drummer Tony Williams and Cream legend Ginger Baker shared duties behind the kit; Frank Zappa’s former guitarist Steve Vai, soon to be forever associated with the likes of David Lee Roth and Whitesnake, provided the solos alongside Laswell’s regular guitarist, Nicky Skopelitis; backing vocals came from Bernard Fowler, who would shortly join The Rolling Stones to provide the same; and even Ryuichi Sakamoto, the founder of Japan’s Yellow Magic Orchestra, also known by then for his success scoring the David Bowie vehicle Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence, made significant contributions. The members of PiL, however – aside from Lydon himself – were entirely absent from the sessions. Not that anyone could really tell: the artwork credited only songwriters and producers.

All of this only mattered to the tribalists, those who still clung to the idea of Lydon as a spokesman for a cause that had by now been reduced to little more than groups of mohican-hairstyled individuals asking tourists for money in the Kings Road. The rest of us – those willing to welcome the record without associated historical baggage, or too young to recognise that baggage for what it was – heard something entirely different, the sound of a man taking risks and broadening horizons. And, to Lydon, it was entirely unimportant who played the notes anyway. What mattered was the result.

"I don’t give a damn if the musicians I’m working with are old and got beards and long hair," he told Smash Hits in February 1986. "That’s nothing to do with it and never has been. It just goes to show how narrow-minded people can be. I don’t give a damn. It works."

Even so, it was a shock to hear the voice of The Sex Pistols fighting for space with screaming axe solos amidst such slick, bombastic production. 1986 may have been the year of Slayer’s Reign In Blood and Metallica’s Master Of Puppets, but it was also the year that Europe’s ‘The Final Countdown’ topped charts around the world and Heavy Metal Parking Lot characterised metal fans as endearingly clueless, long-haired Budweiser drinkers. This was not an obvious environment for the man formerly known as Johnny Rotten, something even he conceded.

"Heavy metal is something I don’t generally like at all," he told Sounds’ Jack Barron. "But I’ve never worked with it, so I quite fancied having a go. If anything it’s almost suicidal for me to go into those fields. And that’s precisely more reason for me to do it. I enjoy the challenge."

He went further in an interview with Kerrang!’s Howard Johnson. "(Heavy metal is) apparently a great evil, isn’t it? Well, I’m not having any of that, because that’s not the fucking case! I’ve thought for years that there’s very little difference between punk and heavy metal. Aside from image, it’s the same bloody music. It’s about the same energy. I like Van Halen, I like them lots, and that drives people up the wall, but it’s an honest statement."

It was perhaps because Lydon seemed so firmly against the idea of making assumptions that I now warmed to him so fast, having previously shown little or no interest in the man. "I will not have prejudice in music," he continued in his chat with Kerrang!, and the idea that even a man who had entirely rejected the establishment thought better of discrimination was comforting, to say the least. Normally I only needed to leave the school grounds and take a wander into the local village to risk being showered with rocks, purely on the basis of my school uniform, by residents I’d never met, and yet here – even if, once again, I was merely reading into his words the very thing I wanted to hear – was Johnny Rotten claiming that background was of little importance. "I never approach music in terms of pigeonholing," he said. "That’s not what it’s about. I buy all music by all kinds of people in every form and every field." And that, to me, meant even posh boys had a chance.

Whether I had any right to think this way, it’s a similar philosophy that lies at the heart of Album. Lydon was no more forgiving than before of a world that wound him up ceaselessly, and the record is as full of twisted, gnarled invective as anything he’d released. But it seemed to be about him bringing his fury to a new crowd by working with the kinds of musicians who stood against all the amateur, DIY aesthetics of his past, even at the expense of those who’d followed him for years. Against all the odds, it worked. "I never thought this album would be commercial in any shape or form," he told the late Carol Clerk in an interview for Melody Maker in May 1986. "I thought it would be the absolute kiss of death for me. I grabbed rock & roll by the testicles. I wasn’t interested in anything other than I wanted to be uptempo with a serious content." And yet, as Billy Ocean topped the charts with ‘When The Going Gets Tough, The Tough Get Going’, ‘Rise’ rose to number 11, while Album peaked at number 14.

‘Rise’ was the calling card, a simple guitar arpeggio and bass line atop a shuffling beat pinned down by fierce strikes of the snare drum, signified in the video by the violent beating of carpets. It was at odds with everything else that penetrated mainstream radio, still the source of most of the records my 14-year-old ears heard. The music, however, was nothing compared to the sound of the voice. I tried to play the song in my school band with one of my few friends, Olly, but we couldn’t get even close to matching the original. It sounded unimaginative, even puny, in our hands, and when I started to sing I was embarrassed. I couldn’t match Lydon’s hysterical delivery, the way his voice lifted at the end of each line as though he was hurriedly biting the last word between his teeth. I just sounded like my voice was breaking. He seemed to be wagging his finger at us in warning, eyes wide and deranged under an orange frightwig whose dreadlocks were held in place by wire. I, meanwhile, was as dangerous as Aled Jones. There was also that mysterious imprecation in the chorus, a chant whose words matched their meaning through their melody – "May the road rise with you" – and a breakdown three minutes in that sounded as though someone was throwing furniture around the studio to the accompaniment of a lone violin. This, we swiftly realised, was not an easy trick to pull off, so we returned to our cover of the previous year’s big Bryan Adams hit, ‘Summer Of ’69’.

‘Rise’, however, was just the beginning, the hook to lure us in. Album might only contain six further songs, but they were enraged, overflowing with bile and contempt, fuelled by a righteous disgust at the world around Lydon and even the people closest to him. Opening track ‘F.F.F’, which begins with such a head of steam that I often had to restart it so I could enjoy it properly, is a vicious valediction to what he called the music industry’s "clingers, dead wood, dead weights", though former PiL drummer Martin Atkins in particular, who’d left the band in a state of significant unhappiness, took it more personally. If his theory that "Lydon merely fuelled the shit-storm with his betrayal" is true, then one can only imagine how miserable he must have felt when he played Album for the first time. "Farewell my fair-weathered friend," Lydon spits over drums slammed liked doors and a wall of chugging guitars, "on you no one can depend." And the insults – as acerbic as they are imaginative – continue to rain down: "Logic is lost in your cranial abattoir," "Shallow, empty inside, / Sly witted, full of snide", "The shutter-speed of your thinking process is small, too small." Lydon might have embraced the sound of Los Angeles, but he’d lost none of his spite, and the pace of the song – Lydon barely drawing breath between each burst of abuse – is almost as cruel as the diatribe itself.

‘Fishing’ is no more friendly with a riff like logs being chopped. Ginger Baker’s drums, underlined at the start by an explosive effect at the beginning of each bar, like factory machinery. And Lydon again – naturally – berating his subject with loathing: "Talking to you is a waste of time," "Go crawl back into your dustbin," "I think you’re stupid / But you’re worth the mention" and, ultimately, "People who need people / Are the stupidest of people", a line in which I took great pleasure given my own inability to make friends. Steve Vai, meanwhile, flails in the background, squeezing out feedback until the song fades as his fingers speed across the fretboard. His playing, however, seems strangely unconventional, even if his guitar tone conforms to contemporary styles, and this is perhaps due to the manner in which, according to his website, he laid down his guitar parts over two days. "Some of the material I’d never heard and just went in and started playing on it," he recalls, and its spontaneity does indeed seem intact, even instinctive. Furthermore, it’s given an entirely new context, Laswell’s production – digitally polished though it might be, and as sacrilegious as this may sound – not a million miles away from the intense, abrasive claustrophobia that Steve Albini was to achieve with Big Black’s Songs About Fucking a year later.

This wasn’t the mainstream metal that had been adopted as an act of rebellion by some of my school contemporaries – Iron Maiden employing guitar-synths on Somewhere In Time, Van Halen with Sammy Hagar, Bon Jovi fnarr-fnarring with Slippery When Wet – and it definitely wasn’t about bouffant hairdos and bare breasts on giant stadium screens. This was more violent, more aggressive, than the preening and posing with which I was familiar, and that, surely, was Lydon’s goal: to find common ground between his punk roots, post-punk and metal, "the same bloody music" as far as he was concerned. It was, in many ways, the punk and metal I’d always wanted to hear but had, up to then, never found.

Of course, it was all filtered through Lydon’s own widespread musical interests, though whether one can genuinely claim that his well-known love of Krautrock was responsible for the use of repetition through the album is debatable. But it was true that the foundations of the album’s various songs were all fairly modest: simple riffs repeated ad infinitum, drums powerful and largely frill-free, lyrics oft-repeated, Lydon circling the root notes of each melody, ranting and raving like a demented creature possessed. Most of all, though, the record was disciplined, tight and supremely confident. And, if at times it became too much, if sometimes he seemed to be treading the same ground – as on ‘Bags’, where the formula is perhaps stretched a little thin, with only Sakamoto’s keyboards and Lydon’s especially agitated delivery lifting it above a relatively plodding beat – there were always the lyrics, ripe with images of vultures in Arizona skies, the titular "black rubber bags" and a "bloated body like a TV dinner".

There were also tracks that played with the formula: ‘Round’ is slower and shorter (a mere four and a half minutes), and opens with Sengalese drummer Aïyb Dieng’s percussion and Lydon’s cyclical chant – "Round and around / Around, around, round, round" – before guitars, stripped back to the level of ‘Rise’ (if still highly present) reclaim the song for a lengthy bridge. Closing track ‘Ease’ also messes with expectations, kicking off with way over a minute of Eastern drones and Steve Turre’s didgeridoo. Ginger Baker arrives eventually to beat the kit once more, and a solitary guitar chord, then a single note, reverberate menacingly, but it was always Lydon who held my attention. I’d never heard revulsion like it. I never even realised I wanted to express such emotions. But lines like: "Cruel fool / Idiot and spastic / Dutch courage / Talking like an ashtray" knocked the superfluous politeness out of me with a welcome force that I absorbed and tried to channel, while even the final lines – "Susan and Norman / You’re so normal" – were so loaded with sarcasm that his intent was clear. In case it wasn’t, however, that Smash Hits interview, Blu-Tacked to my study wall, made it clear. "No, I do not miss England at all," Lydon clarified. "It’s pretty dreary here, isn’t it? So bland! Don’t be bland! Don’t be bland, Susan and Norman, you dreary couple with the Ford Cortina and your names on the windscreen. There’s actually a Susan and Norman out there right now, driving around in a blue Ford Cortina feeling well proud of themselves for being utterly dull…”

A model citizen: the very thing I was expected to become, the very thing I didn’t want to be, and the very thing that Lydon so articulately, so easily, ridiculed, while around him his band unlocked dark corners of my soul into which I had crammed my growing indignation. Right time, right place, right message. "Bad times, they must end…"

Eighteen months later – November 3rd, 1987, to be precise – my pal Olly and I stood in the cold air of Kilburn High Road, orange street lamps the only hint of warmth. It was the first time I had ever been allowed by my family to attend a concert – Olly had seen The Cult once, but even he had chosen to withhold the information from his parents that John Lydon was in fact Johnny Rotten – and the dark winter streets of North West London were far from our normal stomping grounds. Coming up the rickety escalators of the tube station, we’d felt anxious, threatened, and even selecting a pub where we could drink a beer or two without fear of judgement proved nerve-wracking. When we arrived at The National, there were punks in the queue ahead of us, dressed in ripped jeans and Tippexed leather jackets. We were dressing down in jeans and cardigans that might have passed for ‘trendy’ in the Home Counties, but here they made us stand out like the mohicans around us. I’d expected nothing less, however, and had spent the days leading up to our half term holidays willing myself to have the courage to go through with our plan. And now we were here. We’d made it. We were about to see Public Image Ltd. It was almost as exciting as my first kiss. Maybe even more so now I have perspective on that first kiss.

When the band finally arrived, and the man we were all there to see strode confidently onto the stage, we surged forward together towards the rails at the front, a unified mass of angry, alienated individuals desperate to be a part of a world in which John Lydon was our spokesman. Around us, the punks started throwing themselves at one another, and soon Olly and I joined in, elbows knocking the air out of our stomachs, grins provoked by pleasure and fear in equal measures. We stepped out from time to time to catch our breath, then stormed back in with refreshed relish, until suddenly I noticed a nearby punk tip his head back, and, clearing his throat, launch a lung cookie over the heads of the front rows. It landed directly on the immaculate trousers of Lydon’s lime green suit. He looked down in disgust, pulled a towel off the drum riser behind him to wipe off the phlegm, tossed it away, and then pointed out at the little man beside us, whose defiance was slowly transforming into shame.

"You," he said, his voice dripping with contempt and vitriol. "Yes, you!"

There was a pause as the crowd followed the direction of his finger.

"What a pity," he said, spitting the words drily but with the same accuracy as the punk’s sputum, "you’re such an arsehole…"

He stretched those final two syllables out so they seemed to arc in the air over the crowd. Then, with satisfying velocity, they struck the little punk, and the mosh turned on him, buffeting him with undiluted force around the floor. Olly and I stood back in wonder while the band kicked into ‘Home’, the closest Album ever came to an anthem and the second single it had birthed. "Let’s talk politics," Lydon wailed, as he wandered over a walkway that rose over the back of the stage. "Every dog has its day. For me, I don’t believe in anything."

Nor, any longer, did Olly and I. We simply didn’t know what to believe. We certainly never expected to belong here, but then Magazine’s John McGeoch, now playing those guitar solos like they had been his all along, and Pop Group drummer Bruce Smith, now pounding the drums as though each beat represented another hateful face, didn’t belong here either. They hadn’t even played on the record. And no one had ever expected Laswell, Sakamoto and Vai to belong on a PiL record in the first place. This was the point: it didn’t matter. John Lydon had given us all a home. It wasn’t what we’d done that was important. It was what we did next.

Who cared if PiL had sold out? We were John Lydon’s new disciples, he was our conscience and now he was speaking our mind. "You’re being fed nothing here but this small little narrow-minded attitude about ‘This is the centre of the universe and the rest of the world stinks’" he told Smash Hits. "As if this little island, this ‘sanctuary’, is the only sane place on earth. Well, it isn’t."

We didn’t need to be punks, but nor did we need to be arseholes. The road would rise with us. Anger was our energy. And John Lydon, Public Image Ltd. and Album had changed our tiny, conventional lives forever…

PiL’s Album and their entire back catalogue bar Metal Box, are reissued by Virgin this week