When the greatness of Public Enemy is discussed – which is often, for the band were, and indeed still are, one of the most consistently inventive, provocative and excellent outfits of the recorded-music-as-business era – the focus inevitably falls on their second and third albums. It Takes a Nation of Millions To Hold Us Back routinely turns up near the top of the all-time lists assembled by people who care about ensuring their opinions are thought sage; Fear of a Black Planet, its follow-up, is actually its better, though its sonics had been well enough trailed and it perhaps therefore lacked the element of surprise. Yet the band’s fourth LP is almost always overlooked.

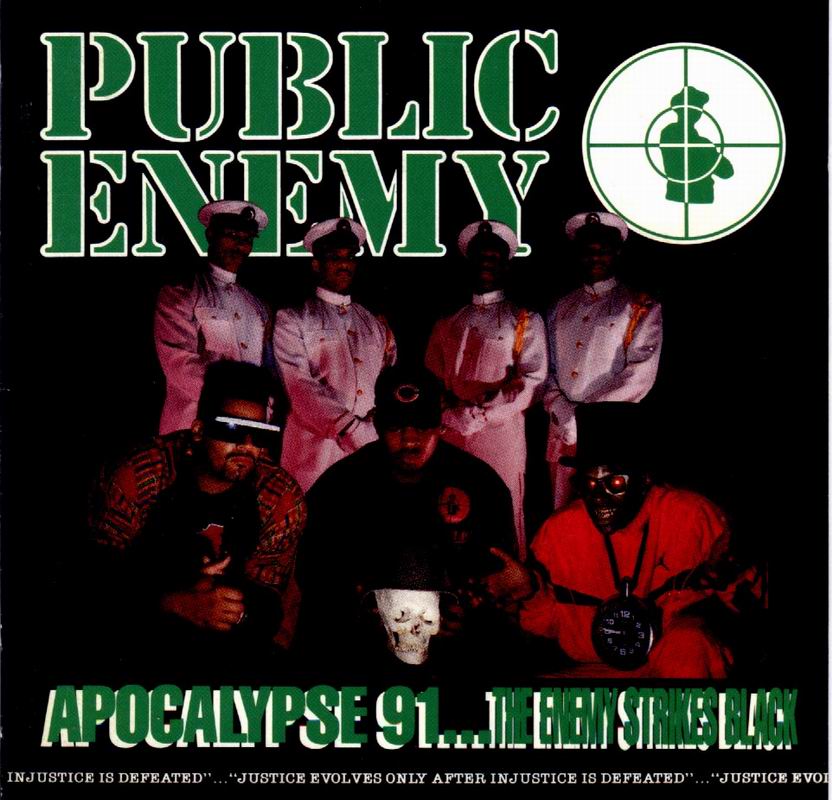

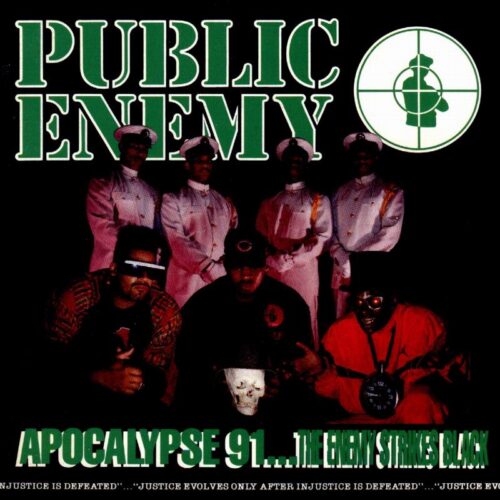

A lack of the shock of the new is only part of it. Apocalypse 91: The Enemy Strikes Black was – as its gloriously convoluted title makes clear – something of a direction-change from PE leader Chuck D. The previous three albums had performed very clearly defined roles in paving the way, and in many respects, Apocalypse… was the record which, thematically, the group had been building up to. But its messages were their most controversial and the presentation of them the most risky the band had yet attempted.

The group’s debut, Yo! Bum Rush the Show, was an exercise in establishing these very different newcomers in 1986’s already very rigidly codified hip hop landscape. There were a number of marks in the "against" column when PE first came out. Hip hop was a young man’s game – LL Cool J’s debut was released when he was 15; Rakim was 16 when he wrote most of Paid In Full – so Chuck, at 26, was already beyond the upper limits of the emergent rap icon demographic. Their shunning of accepted rap star visual style put the group on the fringes of what the nascent hip hop establishment deemed "real" – in a mid-’90s piece supposedly timed to coincide with the release of Flavor Flav’s solo LP (they were only about 15 years early), The Source argued that PE might have been dismissed as "alternative rap" and lumped in alongside the likes of the Disposable Heroes of HipHoprisy (generally considered "rap for people who don’t like rap" by those who did) were it not for Flavor’s persona firmly connecting the group to the street. And in terms of lyrics, political engagement wasn’t in fashion: so Chuck rapped about cars (‘You’re Gonna Get Yours’), girls (‘Sophisticated Bitch’) and how badass he was as a rapper (‘Public Enemy Number One’), using the genre’s established tropes to rope in the curious and get them to hear his meatier manifestos (‘Rightstarter’, ‘Timebomb’).

The first album didn’t do that well commercially but it built the group a beachhead. The arrival of …Nation… – trailed carefully, if accidentally, by ‘Rebel Without a Pause’ and ‘Bring the Noise’, singles that expanded their fan base out beyond hardcore rap fans and into the kind of adventurous alternative music audiences who always gravitate towards experimental, envelope-pushing sounds – was probably the first flowering of what Chuck really wanted the band to do and say. Despite the controversial circumstances of its creation, Fear… was a record made by a band in a position of strength – certain of their fans’ fealty, established as important musicians, the eyes and ears of a growing global audience ready for the next instalment. And by building on …Nation…‘s foundations, Chuck was able to put a bigger plan into action. The "Black Planet" in the title wasn’t just a nod to the genetic inevitabilities essayed in the title track – it was a record that sought to explain the nature of the black American experience to the rest of the world.

So they’d spoken to rap fans, rock fans and everyone else: where was there left to go? Back to the roots, of course. Apocalypse… was to be the first PE album since the debut to set out deliberately to address the communities Chuck, Flavor Flav, Terminator X and the Bomb Squad came from: and it marked the first time they were able to speak primarily to that audience knowing that what they had to say would be heard. But these weren’t globe-conquering sons returning home ready to kick back and party: the album lasererd in on the most self-destructive aspects of black American society and set out to put things right. That they chose to do so over tracks which – by their hyperventilating standards – sounded almost conventional seemed to seal the deal: Apocalypse… was doomed to be received as PE Lite: a good record, but disappointing fare from a band who’d previously made overachieving seem de rigeur. It may have been an understandable reaction – but it was wrong.

All three previous albums had been produced by the Bomb Squad – Chuck, under his "government name", Carlton Ridenhour; brothers Hank and Keith Boxley (they went by the nom de sonic guerre Shocklee); and the Shocklees’ long-time confederate, Eric "Vietnam" Sadler. The Squad name was first used on …Nation…, when Chuck elevated an already honed

sloganeering style, but the personnel were in place (and credited as named individuals) on the debut. Apocalypse…, though, saw the Squad relegated to the role of executive producers – overseers of the sound rather than its principal architects. The grunt work was done by an outfit billed as the Imperial Grand Ministers of Funk: collectively, Stuart Robertz, Cerwin "C-Dawg" Depper, Gary G-Wiz, and The JBL. The sound they gave the record was at first simpler and more direct: it was also ever so slightly closer to the hip hop of the day – many of the tracks relied heavily on sample loops that stood prominent in the mix rather than densely packed sonic collages, and, for a change, lots of the constituent parts were clearly recognisable, both as their original compositions, and as music in general.

This wasn’t in itself a first – ‘Don’t Believe the Hype’ was basically just one loop from James Brown’s ‘I Got Ants In My Pants’; a section from Isaac Hayes’ ‘Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymystic’ had provided the lion’s share of ‘Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos’; and, infamously, a looped bar from ‘The Grunt’, a 1969 45 from the sole J.B.’s recording session when Bootsy Collins was part of the band, gave ‘Rebel Without a Pause’ its kettle-left-on-the-stove squeal (even if bowled-over rock critics, back in those pre-internet days where finding or listening to old records wasn’t quite so easy, bent themselves into contortions trying to claim that the Bomb Squad had made the sound from a treated series of Brown samples). But Apocalypse… sounded less like PE, and perhaps a little more like ordinary hip hop. For fans accustomed to ever-increasing levels of dissonance, its musclebound musicality probably seemed a little underwhelming.

The supposition was that the fallout from the Professor Griff/Washington Post controversy had caused a schism behind the scenes – something Chuck has acknowledged since – but Griff’s principal contribution to the studio part of the PE experience was his collection of spoken-word samples from black nationalist political speeches, so his absence (he was replaced by Sister Souljah, his Minister of Information title retired while she donned the twin mantles Sister of Instruction/Director of Attitude) didn’t have a huge impact on the record’s sound. There was also mileage in the theory that the Squad’s in-demand status and phenomenal workrate (in 18 months they produced Ice Cube’s solo debut, the dazzling Son of Bazerk masterpiece Bazerk Bazerk Bazerk, and albums by Young Black Teenagers and Bel Biv Devoe as well as Fear of a Black Planet) had taken its toll. But this altered sound had a more prosaic and functional explanation, one that wasn’t made public for decades.

"There was a couple of things that happened at that time," Hank Shocklee told me in 2008. "One was, we had… I don’t wanna say a robbery; but what happened was, as we were coming out of the studio, we had all our disks of every song that we’d been working on for the past four or five years with us, and it got lifted out of the studio. So we were rushed – not just to put it [Apocalypse…] together, but to create it, because once you lose all your data, it’s very difficult to get that data back. I mean, you may get some of it back, but you’ll never get the complete set: you won’t even know what the complete set is, because there’s data in there you didn’t really know you had. So when we lost all our material, that was like a funeral for me, man. That was a very, very dark time, and it kinda stunted our growth. We never really recovered after that. We was on a roll – I was on a roll; and to lose that material set me back so hard."

So if some of the tracks sound like a group reaching for a sound and not quite being able to grasp it, there’s the reason. That some fans heard in this new PE a deficient, less acerbic or individual, version of their earlier incarnation was perhaps partially justified, but to concentrate only on what’s different this time round means missing what the enforced circumstances brought out of the expanded production crew. Live musicians

were added to the brew for the first time, augmenting what was always going to be the necessarily restricted selection of samples (…Nation… and Fear… were constructed, Shocklee says, from literally hundreds of samples, some all but inaudible until you try to reassemble the track without them). And while there are times when PE sound almost conventional on this record, there’s still no-one else that could have made these tracks. ‘By the Time I Get to Arizona’ is a simple trick – take one fuzz-jazz-funk loop by multi-cultural New York ensemble Mandrill, stick a few programmed drums on it, add a choir – becomes little short of musically monumental in these skilled hands. The Bomb Squad may have lost some of their tools, but they had retained all their techniques.

The themes this new music supported also may have underwhelmed some, and it’s little wonder that certain sections of the PE listenership were bemused to find the prophets of rage getting hot under the collar about some rather parochial concerns. On the face of it, ‘How to Kill a Radio Consultant’ is just self-serving umbrage, Chuck berating playlist compilers for ignoring his band; ‘Letter to the New York Post’ can be read as a slightly less-than-charming mea-culpa from Flav (he doesn’t deny hitting his girlfriend, just doesn’t like the way it was reported in the

tabloids); and ‘Shut ‘Em Down’, especially when taken in tandem with the ads for the band’s Rapp Style clothing line carried on the inner sleeve art, just a moan about sportswear companies making a killing off the hip hop audience by a band whose competing range wasn’t shifting as many units. ‘Get the F— Outta Dodge’, too, can sound like sour grapes – a rapper crying about being pulled over in his car for playing hip hop too loud. But even these tracks carry insight and depth; and elsewhere, the record was – and remains – political dynamite.

‘…Arizona’ is the obvious standout, Chuck berating the state for its refusal to observe a US national holiday for Martin Luther King. It remains among the most prescient pieces in PE’s output, lent new resonance by the same state’s 2010 enactment of immigration laws roundly derided as racist. ‘Can’t Truss It’, the mighty first single, was the first time PE really got the most out of the promo video medium, the clip adding depth and nuance to the audio’s harrowing tract on the slave trade by telling two different stories that underscored the unchanged nature of America’s racist power structures. Those supposedly less resonant tracks also chime louder down the years: in the midst of the hacking enquiry, a rant about the tabloid press feels timelessly apt, while ‘Shut ‘Em Down’ prefigured the anti-globalisation movement in calling for consumers to choose the local over the multinational. And while the New York ordinance against bumpin’ rap loud in your car was real enough, racial profiling was the bigger issue the song rather more subtly addressed.

But it’s on the tracks where Chuck "strikes black" that the record’s intent is at its clearest. From the outset, the mood is angry, and the target of much of Chuck’s ire is his audience’s often wilful ignorance. In ‘Lost at Birth’ he makes clear who he’s going after: "I test the front row," he rails, in a song that would become the band’s best ever live set opening track (indeed, its extended opening, sonically introducing first the S1Ws, then Terminator X, then Flav and finally Chuck, only made proper sense on stage), "Forgiven the givin’ while the livin’ is livin’ it up/So many people sleepin’ while standin’ up." ‘Nighttrain’ lacerates crack cookers and dealers, calling them traitors to their communities and their race. ‘…Radio Consultant’ specifically goes after black radio executives Chuck critiques as selling out their listeners by favouring less militant sounds over rap.

Even Flav gets in on the act on what remains by far his strongest showing on any PE album; in all the band’s catalogue there aren’t many tracks that are more abrasive than ‘I Don’t Wanna Be Called Yo Niga’, wherein the supposed clown prince of rap calls time on the use of the N-word in a song that uses ugly brute force and blank repetition to achieve something beyond eloquence. In 2008, Shocklee paid tribute to multi-instrumentalist Flav’s incalculable, if unplanned, impact on the PE process: "In ‘Can’t Truss It’, Flav says a part in the song, and the engineer recorded too much of him, but I kept it," he said. "He was supposed to say his back line part, then he was supposed to stop. But they kept the tape running on. There’s a part where he says ‘Yo Hank! Don’t stop me!’ That’s in there because of the emotion that I got from it. It didn’t have nothin’ to do with the song! But the way he said it gave the song so much tone and colour. Flavor always added release in a song. In Public Enemy, Chuck is the throttle, Flav is the brake. One of the problems I have with modern music today is that everything’s on full throttle. Where’s the release? Where is the thing called dynamics? Dynamics is all about release. The reason I could be full-throttle musically with Public Enemy is because I have Flav to give you the release in the vocal tension."

There were – and still are – problems with the album. It was the first PE LP to arrive on two pieces of vinyl, presumably a reaction to the uncomfortable shoehorning of all of Fear… onto two overstuffed sides; but the "four halves" of the album broke up the flow for a fan base still conditioned to think of an LP as primarily an on-wax event, and ensuring that certain transitions – particularly from ‘Can’t Truss It’ to ‘…Yo Niga’, in which the horrors of the former become a set-up for the ugliness of the latter – lost their impact on the record’s defining format. The closing collaboration with Anthrax, and the two bands’ subsequent co-headline tour (shunned, in the UK at least, by a large proportion of PE’s core fanbase), helped lend the album an air of conventionality – as if PE were working hard to embrace the musical mainstream and issue entreaties to rock fans, when in actual fact they’d already done more to attract outside interest simply by being themselves. That the collaboration was on an old song – ‘Bring the Noise’ – and that it appeared after another old track (‘Get the F— Outta Dodge’ had been a b-side to the last single released from …Black Planet), emphasised the relative lack of new material (there are only 11 other full-length songs, where the previous two albums had clocked in with 16 and 20) and made the whole feel less substantial. All of which has helped to obscure the record’s very real legacies and influence.

In apparent acknowledgement of the changing nature of the rap game, the band acquiesced to outside remixing for the first time (and, in Britain, DJs and collectors reaped the promotional whirlwind as Def Jam/Columbia released exquisite coloured vinyl 12" promos of the album’s first three singles in die-cut sleeves). But even here, at what seemed to be their most conventional, Chuck & co took risks. The band brought in Pete Rock, who reputedly did his two remixes in a single 12-hour session. His blistering retread of ‘Shut ‘Em Down’ (the rapping producer/DJ even managing to deliver a cheeky verse) remains one of the greatest PE moments of them all. Three years later Pete was a star contributor to Nas’s acclaimed debut, in the middle of a string of productions that helped redefine the sound of New York rap – but when he was drafted for Apocalyptic duties he was a left-field pick. Jay-Z doesn’t admit it in Decoded, but the verse of ’99 Problems’ where he plays both sides of the conversation between his drug-dealer self and the cop who’s pulled him over is leavened with a twist of True Mathematics’ Sgt Hawkes from ‘…Dodge’. Years later, DJ Premier was still sampling Chuck’s lines from Apocalypse… when producing for Biggie (and causing Chuck to go legal, resenting how his voice appearing in a song about crack dealing could appear to be lending his approval; that this album, of them all, should provoke such a spat seems beyond apt).

Apocalypse… worked then and still works now for all the reasons Public Enemy records always work. The sound may have changed, but it’s still unique. The one-liners and couplets Chuck delivers here are up there with his best – "I like Nike, but wait a minute/The neighbourhood supports, so put some money in it"; "Neither party is mine, not the jackass or the elephant"; "Why pop the rhyme on the rhymer when he kick it?/I’d rather spend my time spittin’ on a bigot". There’s Flavor, shining more brightly here than at any other time in the PE discography, and his interplay with Chuck – intuitive and accidental though it may be – gives not only the sense of drama, tension and release Shocklee noted, but a breadth of characterisation and range of voice that helps the record ascend.

But best of all, and notwithstanding the harrowing themes and relentless sense of direction and purpose of the album, Apocalypse ’91… stands revealed as a moment of triumph. Here was a band completing the first stage of a long-planned journey, bloodied but unbowed, confident in their ability to communicate and to invigorate. The Anthrax team-up may be

the least fulfilling part of the record in some ways, but it’s a great grandstand finish – a cover version of a three-year-old song that saw Chuck convinced that PE would "never be accepted" by the rock establishment, but with those lines being rapped by members of a rock band, who end up humming and doo-dah-ing what was, in the original, a scratch solo. Job done.