The vinyl spins and the needle drops. There’s a brief crackle, like fat spitting in a frying pan, and then there’s a voice. "All that we see or seem," it says, its vowels clipped, "is but a dream within a dream". A lone horn calls out a melancholic fanfare before the curtain rises and a rhythm track begins, sparse and rigid, layers of cocooning synth slowly proliferating around it, that horn repeating its call to arms. "Take this kiss upon the brow," the voice continues, its accent frigid yet inviting, "And, in parting from you now / This much let me avow: / You are not wrong, who deem / That my days have been a dream." The sound continues to intensify, its insistent bassline occasionally growling fiercely, piling on synthetic brass, church organs, wave after wave, layer after layer, the voice back again intoning words about a "surf-tormented shore" and "pitiless waves", then gone once more amidst a maelstrom of thundering drums and squealing guitars. The tempest settles in, ferocious, merciless, seemingly eternal until at last the storm clears, the keyboards placid once more, the horn forlorn but still bold, those synthetic strings now shimmering in the sun, the propulsive rhythm of the drums and bass moving us forward. Finally, amidst the same dramatic landscape in which we began, the song reaches its gentle conclusion.

The vinyl pops again. I lift the tone arm and return it to the start once more. This is how I want to remember Propaganda.

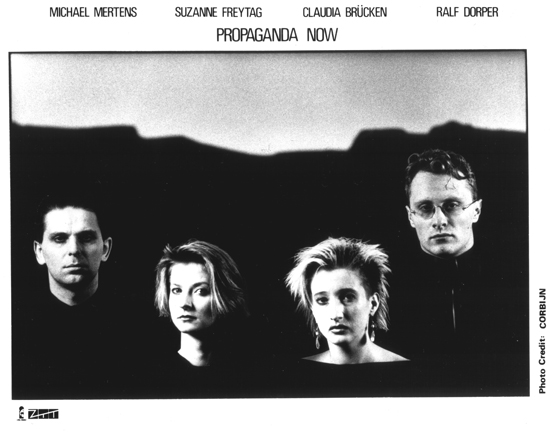

The words are by Edgar Allen Poe. The song is ‘Dream Within A Dream’, the unapologetically colossal, grandiose opening to Propaganda’s A Secret Wish, a debut album so deliciously ambitious that to this day it remains one of my most played records. The first band that journalist Paul Morley wanted to sign to the nascent ZTT Records that he’d set up with Trevor Horn and Horn’s partner, Jill Sinclair, Propaganda were German, from the same city – Düsseldorf – that had given us Kraftwerk. But they couldn’t have been more different, despite their festishisation of industrial machinery and technology: Kraftwerk were all about repetition, about minimalism, whereas Propaganda were almost their polar opposite, bombastic and theatrical, Shostakovich to Kraftwerk’s Stockhausen. They fitted the ZTT vision perfectly, however. Founded with vocalist Susanne Freytag and artist Andreas Thein, by Ralf Dörper, a member of industrial act Die Krupps, they combined limited traditional musical abilities with a love of the avant-garde and art, the perfect playthings for a conceptualist like Morley and a studio virtuoso like Horn. Signed on the back of ‘Disziplin’, a track inspired by Throbbing Gristle’s ‘Discipline’, they immediately regrouped, bringing in Freytag’s friend Claudia Brücken to sing – something that led Dörper to admit recently that "too much of Susanne (Freytag) somehow got lost in production" – and Michael Mertens, a classically trained percussionist for the Düsseldorf Symphony Orchestra. Thein, meanwhile, made a quiet exit after their first recording sessions in the UK at Horn’s Sarm Studios.

There were three acts on ZTT at that time: Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Art Of Noise – Morley and Horn’s innovative collaboration with arranger Anne Dudley and studio engineers Gary Langan and J. J. Jeczalik – and Propaganda. If Frankie were the garish cartoon gang and Art of Noise the bespectacled nerds in the science lab, then Propaganda were their fearsome, gothic nemesis. And if Frankie’s Pleasuredome was the twin-towered palace that ZTT built and Art of Noise’s Who’s Afraid Of The Art Of Noise was the air in which they built it, then Propaganda’s A Secret Wish was its velvet-lined dungeon, dangerous and erotic. In fact one publication – Morley credits Time Out – christened Propaganda ‘Abba-In-Hell’, a soubriquet that Andrew Harrison’s short but sharply observed sleevenotes clearly endorse: "two girls and two boys, two sides to the music, light and darkness…" But this observation was actually too old-fashioned and simplistic for a label with such a futuristic agenda. There are surely more complex states than Christian visions of heaven and hell, and it was one of these that Propaganda inhabited: largely monochromatic, punctuated by brief bursts of saturated colour; sleek and shiny, but oozing an alien life of its own. If this was an incarnation of Abba then it was in a universe where emotion was largely communicated through its absence, language was constantly mutating, movement was stiff but elegant, glamour and intelligence were weapons to be feared, drama the ultimate goal.

By this point, Horn’s involvement with Frankie had become all-consuming, making him unavailable to follow up his production work on Propaganda’s ZTT debut single, ‘Dr. Mabuse’. David Sylvian was apparently considered, as were Stock, Aitken and Waterman – allowing Morley the opportunity to refer to Propaganda as ‘Deutschmark’ to SAW’s ‘Dollar’ in Harrison’s sleevenotes – but the producer’s job eventually fell to Horn’s engineer, Steve Lipson. It was an inspired choice: so successful was Lipson at embracing Horn’s techniques that it’s a shock to remember Horn wasn’t behind the console.

Thirty-five years later, A Secret Wish is no longer so secret, and the 2010 reissue no doubt further boosted its reputation. Curator Ian Peel’s exhaustive research, exhibited in his own contribution to the accompanying booklet, match the care and attention he has lavished on other ZTT re-releases, and the wealth of material he has accumulated – 152 minutes in total – shed fascinating light on the working methods of both the band and the label. Just like Frankie, Propaganda were martyrs to studio boffinery, and the album is here presented in both its original form and that of the digital release that followed some months later, a version that saw Lipson elaborate on a number of tracks. A second disc presents further mixes and rarities, including extended ten minute versions of ‘p:Machinery’ and ‘Sorry For Laughing’.

It’s the digital version that leads Disc One and, as someone who grew up with the LP, it’s slightly disconcerting to get screwed by ZTT’s remixology right off the bat. After 25 years with the original analogue mixes, Lipson’s subsequent tweaks seem distracting: it’s easy to feel cheated by the loss of certain mini-dramas and frustrated by the unnecessary extensions included on ‘Dream Within A Dream’, for instance. But this was the ZTT aesthetic, as though these fiercely mechanical sounds, bigger than the people who gave birth to them, had a life of their own and a shape that could alter at will. To belittle these variations is to miss the point, especially given how we encourage artists to adapt songs for the live arena, and the six out of nine tracks that were in some way altered are included at the end of Disc One anyway. Furthermore, the bonus tracks show you just how far they were prepared to go in their pursuit of imperfect perfection: the deranged shrieks at the start of the coruscating ‘Jewel (Cut Rough)’ – taken from ‘Do Well’, a twenty minute cassingle pieced together by Morley and engineer Bob Kraushaar before album recordings were even complete – are almost worthy of Diamanda Galás, and ‘Thought’, an instrumental re-recording of the Throbbing Gristle track that got them signed, is a relentlessly cantering assault that understandably set Morley’s ambitious mind racing.

These alternative mixes are an admission that much of Propaganda’s work is studio trickery, what Andrew Harrison calls "a self-magnifying hall of mirrors", though their success or failure is less important than their existence as experiments in the first place. But does rare tune ‘Wonder’ – a merger of ‘Jewel’s percussion track with what sounds like a keyboard audition for Mike Oldfield – add anything to the Propaganda myth? You’d think not, since it’s taken from that ‘Do Well’ cassingle, the sound of Morley faffing around as he fulfils every music journalist’s dream by actually being involved in music-making. Since this was the era in which ZTT was arguably as exciting as any band it signed, however, it’s at least worth investigating such material on a historical or cultural level once you’ve immersed yourself in the very heart and soul of A Secret Wish itself. A track like ‘Testament One’ – obviously simply another element of what made up ‘Jewel’ – hints at treasure buried within the so-called ‘originals’, and the joy of ‘Die Tausend Augen Des Mabuse’, Horn’s ten minute take on ‘Dr. Mabuse’, is not in the version itself so much as the way it peels layers back off the song, shedding new light on the original, opening ears – just as stoners always hope a joint will – to new sounds and phrases never noticed before.

So what of A Secret Wish itself, the reason we’re all here? Its heart of darkness is ‘Dr. Mabuse’, of course, a vast canvas across which they throw dark, sinister shadows. Its theatre and spectacle are heightened by the triumph of Mertens’s vision, the merging of his orchestral training with the pop demanded of the band by ZTT, and bear a similar weight of trepidation to the movies of Fritz Lang that inspired it, from Brücken’s opening words – "Why does it hurt when my heart misses the beat?" – to her anguished parting shot, "Never look back…" It’s synthpop at its finest, a simple bass riff industriously stamped out while a keyboard line that John Carpenter might have created flits deftly in the background. Then there’s ‘p:Machinery’, its initial Atari effects obliterated by a jackhammer beat and Satanic voices booming out the chant, "Power! Force! Motion! Drive!" until the band are officially introduced – "Propaganda!" – and another of those simple but thundering Synclavier basslines kicks in. A simple keyboard melody chimes above – contributed by David Sylvian, and not unlike one of Japan’s – ushering in the verse, Brücken’s voice intoning lines about a post-human society in which "on joyless lanes we walk in lines / a calm but steady flow". Its bleak outlook is somewhat offset by outbreaks of brass that perhaps only really sounded authentic when we were all blinded by science, but it’s still a tour de force, massive, intimidating, especially in the belligerent bridge and the almighty drop that precedes the outro, a moment of almost intolerable tension.

The big hit, of course, was ‘Duel’, an unexpectedly jaunty number (later covered by Sophie Ellis-Bextor and, oddly, Mandy Smith) which, even though it’s introduced with typical ZTT pomp by a grand piano, nonetheless conveys a sense of film noir melancholy off the bat, largely thanks to Brücken’s voice, which often sounds like it’s squeezing its way past her tonsils. The lyrics she delivers don’t hurt either, the chorus enigmatically, perhaps disturbingly, announcing that "The first cut won’t hurt at all / The second only makes you wonder / The third will have you on your knees / You start bleeding / I start screaming". But the unexpected return of the piano, and a virtuoso performance that somehow recalls Jools Holland’s appearance on The The’s ‘Uncertain Smile’ add some fun – a quality one doesn’t often equate with Propaganda. ‘Duel’ has a dark side, however: ‘Jewel’, an alternative version of the same tune was – according to Harrison’s sleevenotes – provoked by Morley’s loan of a selection of punk records to Lipson. So inspired was the producer that ‘Jewel’ was born the next day, Brücken in the vocal booth "absolutely screaming the vocal’" while Lipson made "wild stabbing movements with his hands" outside. Percussion slams like a factory at peak hours, there are terrifying, futuristic stabs of Phantom Of The Opera keyboard, and then Brücken arrives, her delivery jerky, maniacal yet dispassionate, an impression that, much to its benefit, the record never quite manages to shake off. Her ‘Denglisch’ adds to the confusion, hinting at times that she’s not entirely sure of the meaning of her lyrics, like some automated replicant, something further underlined when her vocal is sped up as though she’s malfunctioning. But when that massive keyboard line arrives towards the song’s end, and the donner und blitzen rumble in the background, there’s no doubt that this is a purely human drama, even if it is inspired by fears for our increasingly industrialised society.

In addition, there’s ‘Frozen Faces’, whose second half could twinkle on a million chillout compilations, and ‘The Chase’, which, after an unsettling start, shifts into the kind of pop that Talk Talk might have come up with before they decided it was more fun in the studio than on the stage. This still refuses to let us off entirely, however, closing with another sinister marshalling of jackhammer beats. And of course there’s the cover of Josef K’s awkward ‘Sorry For Laughing’, an idea so warped as to be inspired (though the bonus ‘Unapologetic 12"’ mix, all ten minutes of it, reveal the song’s Scottish roots a little more clearly with a jangling guitar upfront). Propaganda turn the song into a monolithic tombstone of a tune: Brücken’s oddly glottal delivery, swathed in swaddling synths, lends it the air of a Weiman Republic disco, the disciplined rhythm at its core soothed by the promise of imminent, intimate contact, however lonely it might be. Finally there’s ‘The Last Word’, whose keys – Daft Punk as much as Georgio Moroder – eventually give way to another round of stormy sound effects (later, one suspects, employed by Lipson and Horn on Grace Jones’ ‘Slave To The Rhythm’), a last round of orchestral flourishes and Freytag’s poignant parting query: "Is all that we see or seem but a dream within a dream?"

You’ll need to skip to the end of Disc One to hear ‘The Last Dance’ in its purest form: Lipson’s CD mix chooses instead to force the listener to endure the majestic conclusion to ‘Dr. Mabuse’ segued into a Stars On 45 album megamix before finally giving way to the album’s closer. In fact, if there is a criticism that could perhaps be leveled at this reissue, it’s that by the ‘p:Polish’ version of ‘p:Machinery’ at the end of Disc Two, with its guitar showroom acrobatics, it’s hard not to long for the concise, perfect vision of these songs familiar from the vinyl and cassette releases. There’s a limit to the amount of indulgence one can take, after all, and to have four interpretations of what was pretty much immaculate on the album is perhaps overkill. But these bonuses are mere gravy: the meat is in A Secret Wish‘s analogue mix, and that’s pretty much beyond criticism. Even accusations of pretentiousness are easily countered by the hints of camp cabaret dropped throughout: the deadpan Hollywood voice in ‘Dr. Mabuse’ ("Don’t be afraid!") or, to be frank, Freytag’s entire recitation of Poe’s ‘Dream Within A Dream’.

The vision of A Secret Wish was the apex of ZTT’s musical achievement – possibly even more so than Frankie’s Welcome To The Pleasuredome. Quite apart from its influence on other musicians like Depeche Mode’s Martin Gore and producer / DJ Ewan Pearson, it never underestimated its audience’s intelligence, exploited and overcame German stereotypes and even left its mark on the charts. Furthermore, it was almost perfectly conceived, with Lipson’s production as palatial as anything Horn ever achieved, and the band’s image cultivated by Anton Corbijn in perfect synchronicity with Morley’s vision. The band broke up soon afterwards, caught up – like Frankie Goes To Hollywood and Art Of Noise – in a wrangle of lawsuits, some of them regrouping with members of Simple Minds for 1990’s flaccid 1, 2, 3, 4. Rumours of a reunion of the original line up continue to gather pace following their performance at Wembley Arena for Trevor Horn’s Prince’s Trust concert in 2004. But none of that is important. It’s A Secret Wish that’s important. The power of Propaganda endures…