Saying something new about albums that have been loved and discussed over the moons can sometimes feel like gilding the lily, no matter what approach you can bring to it. Saying something new about Prince and the Revolution’s Purple Rain makes me feel like I should just visit you all individually, give you a gilded lily on top of a copy of said album and then be on my way.

The news in April was that Prince and Warner Bros. are talking again and that songs from the vaults may finally officially emerge. On top of that there’s some sort of remaster of Purple Rain due first, ahead of everything else. This in turn has sparked fever dreams of a combination with The Time’s Ice Cream Castles and Sheila E’s The Glamorous Life and… and… and… etc. This news pretty much dominated music talk among friends for a few days. Perhaps oddly, perhaps not, a parallel to Star Wars and George Lucas emerged too – Prince’s conversion to the Jehovah’s Witness faith has led him over the years to revise lyrics in concert, stop performing some songs entirely. Whether or not this means that a reissued Purple Rain will undergo a ‘special edition’ treatment is unknown to anyone bar the man himself, at least at this time of writing. However this has also led to some talk which can be summed up as, “Whatever happens I’m holding on to my CDs/vinyl/whatever until I hear the reissue.” This type of conclusion would make sense for anyone suspicious of how remasterings are often not all that, depending on the record company in question, but because it is Prince, this is almost more like early believers really hoping the First Council of Nicaea doesn’t rewrite a key gospel.

Of course, that makes sense given that the first thing on the album you hear is a church organ and a preacher’s call to the faithful. Purple Rain is the art created by someone who knows that they have a following, that there are people waiting to listen, and they will listen. Prince probably always felt this to some degree once the first album was off and running but 1999 had sealed the deal two years previously because after that and its singles he was impossible to miss, even among eleven year olds in upstate New York miles from anything. That’s when I finally first heard and saw him, watching the syndicated Solid Gold TV program – as close to an American equivalent of TOTP that existed, even in the early days of MTV – and seeing Marilyn McCoo try to introduce him and the Revolution performing ‘1999’. For the first and only time on the show that I ever saw, the audience was yelping, screaming from the get-go practically before she said anything. Live wire insanity audible but not visible, and then the band actually started performing and that was that.

It turned out that was prelude. The insane audacity of what Prince was able to do with ‘Purple Rain’ is one of those things that hovers in the young brain – equivalent audacities can occur later but they seem to be nothing but poor copies and knockoffs. The actual film still works as heavily stylised craft by cinematic journeymen and non-actors. It’s a white-heat moment where everything comes together, wears all the obvious influences on the sleeves, is a product of its time just so but is more than simply artefact. (If you needed proof it was a one-off moment all around even beyond later Prince films, watch director Albert Magnoli’s followup film American Anthem sometime. Nothing could scream “1986!” more loudly, and calling it cheesy is an insult even to Velveeta. And in comparison to ‘Purple Rain’ the song, this piece of tripe was the later film’s theme song – so, no comparison.) And the music, the MUSIC. The report of the tour, the videos, the TV appearances, the awards, the wall to wall radio playing, the way extended versions of songs started mysteriously appearing on my local Top 40 station instead of the single edits. “Hey, wait, I don’t remember ‘When Doves Cry’ having that ending…”

Which calls up a salient point – I didn’t actually purchase the album upon initial release (think I had it by the end of the year), nor did I see the film in the theatres at the time. As for the album, I almost didn’t need to get it immediately because again, he felt like he was everywhere, omnipresent. Not just him, of course – that summer of 1984 in America was a flashpoint moment where so much suddenly clicked, and even where I was I could hear Duran Duran remixed by Nile Rodgers, Bruce Springsteen remixed by Arthur Baker, Frankie Goes to Hollywood singing about ill-disguised lust and power politics, Madonna still scoring hits off her first album in the run up to Like A Virgin that fall, much more besides. Add in things like Ghostbusters and Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom and Gremlins and more in the theatres. There was the Los Angeles Olympics making all of us feel damn great about our wonderful selves and to heck with them commies who didn’t show up, and a certain Teflon president preparing to coast to a crushing reelection victory and little surprise that summer lingers in the mass memory among people of a certain age as a theoretically golden time. (Theoretically – if you didn’t have to actually struggle in life with a pre-dealt deck, of course it was golden. Those who didn’t have to struggle, never learned how lucky they were in retrospect, and probably just never grew up still light candles to the projections of Reaganism rather than the realities. Sadly this explains a lot about American politics these days.)

Thinking of my claim of audacities, looking back on Purple Rain with a critical eye means overcoming a barrier in one’s head for me, that of teenage imprinting. This is one of those albums – actually, maybe the album above all else – that for me approaches the level of one of those sixties albums which people even then deemed to be a life-changer, man. But that stuff happened already and I didn’t care, really; this I cared about. Now that I’m well away from that time I can sympathise more with those older people going on about albums from their youth that rewired their heads – hey, here I am now, aren’t I? Trying to pick out a song I don’t like or a problem with this album would be a forced exercise so I’m not going to attempt it. Also while trying to imagine how I think about pop without this album as an early framework is impossible.

So what do I get from the album even after all else? Possibilities. Sure, in the grand scheme of things, looking back over the whole musical story of that time now – Prince in the eighties let’s call it – it doesn’t have everything he ever tried or attempted on it. It’s actually a partial reduction – from a double album in the form of 1999 to a single one. It’s just nine songs, anchored and concluded by a theme song for the album and for the film, designed as a huge from-the-heartland anthem. It had one of the most beautifully surreal/sad images in its title, purple as royalty, rain as sorrow, the bomb lurking behind it all, not so much bringing people together as leaving everything flattened in its wake. Except it is the band performance, not the bomb that does the job here instead; as if nukes could actually send you to heaven with musical sublimity. (Like I said, hard to overcome the barriers in my head when talking about this album, or attempting to talk about it coolly. Realistically, I CAN’T.)

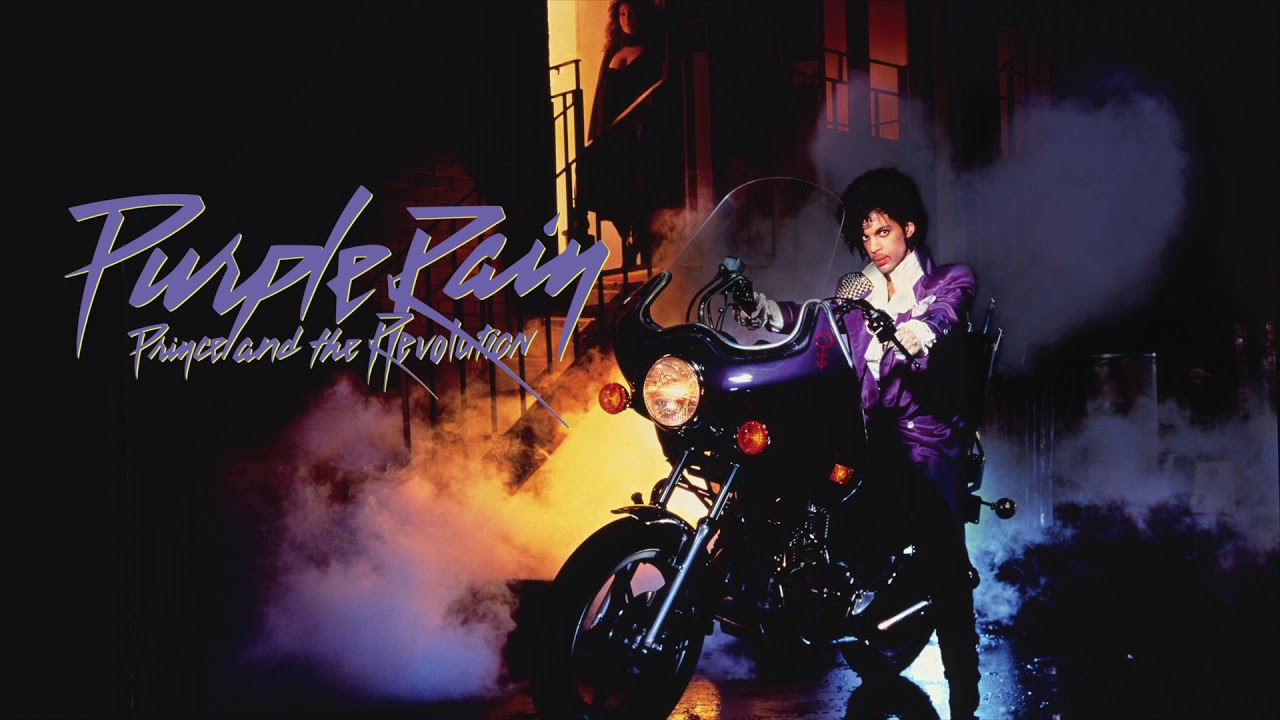

When I think of this album, I think of the poster it came with. I was already used to the early 80s variety of glam-as-such that had filtered through to America – Boy George, obviously, but Duran Duran and the Human League too. And then this poster, what I assume is a posed still from the ‘When Doves Cry’ video set, Prince in hyperfinery, the rest of the band not so far behind, Wendy and Lisa seeming to be extremely comfortable with each other… I’m still kinda surprised my parents let me put it up in my room. (Also how weirdly/strangely amazing it is to me still that besides bringing their own compositional and arranging skills throughout the album, Wendy and Lisa would have actually been the first lesbian couple I ever knew about, heck the first lesbians I think I would have been aware of, period? Hiding in plain sight, but not really hiding at all, and yet I remember plenty of discussions – not exactly of the most elevated sort – among classmates about whether it was all a pose or not, whether or not that opening dialogue on ‘Computer Blue’ was just that, dialogue rather than reality. Prince had them accompany him to the Oscars and when he won the award for Best Original Song for ‘Purple Rain’ itself they came on stage with him and he introduced them both and obviously the implication was that they were ‘with’ him but they weren’t of course and THE SWIRL OF FEELINGS AND HORMONES IN MY HEAD. This is again exactly why this album is kinda hard to talk about as well, but while I won’t exactly embrace my inner young teen dumbass I won’t handwave him either. And thirty years on Wendy and Lisa are even more heroic to me than I would have guessed then.)

So… possibilities. Image informing film, involving video, feeding back into the music. But not just the overripeness at work, which was less that than perfection in luxuriation. ‘When Doves Cry’, after all, isn’t about being overstuffed, it’s about absence. When I first heard it on the radio, mind-blowingly great, when I heard it again and again, still so. When I realised years upon years later, and only because it was pointed out to me by someone else, that there wasn’t any bass on that song at all, I think I seized up a bit. Something so essential, theoretically, to music, something I’d been trained to listen for by socialisation, there was always bass in there somewhere in pop, wasn’t there? It might not be much but it was there – but not here. Prince did that a few more times throughout the eighties on some of his biggest songs and I still didn’t quite pick up on that, it became so much of his sound that I just accepted it as is without thinking or realising why, and that’s how to have an impact just as profound as something immediate, something crushing.

Looking back on a song like that you hear so much of what was to come in future years, one of the cornerstones of the Neptunes and Timbaland empires, where space and silence, the not-playing of notes, would be as much a hook as a hook. But silence and spare approaches can work in other ways and thus ‘The Beautiful Ones’. Oh that’s a song, baby, baby, baaaaa…BY! (I wouldn’t even try to actually sing this. Prince is one of the few people who make me want to sing the impossible, though.) Just the way it starts, barely there, how it slowly builds, how Prince turns from the quiet contemplations and wondering to the shrieking obsession and rampage to…that ending. I love that ending, how everything winds down suddenly, not on a dime, but like it’s all eased back, and while I’m sure the man himself and the surrounding atmosphere suggests something biological taking place across the whole song, say, it’s more weirdly and beautifully mechanistic by the end. Numanish, even, how the final drum hits appear and then it softly, slowly burbles away. Of course it’s the following song that’s called ‘Computer Blue’ rather than this one, but it could have applied.

Some moments were just hard to imagine or get for me, sure. Again, I’m thirteen, I’ve hardly figured myself out and an opening line for ‘Darling Nikki’ is about masturbating with a magazine? I’d learned some things via sex ed but not… that. It didn’t help that the biggest Prince fan I knew then was also seated right next to me in science class, that she was ridiculously attractive and sweetly friendly and that she saw Prince on that tour that year. (What universe was I in that I missed that?) She wore her tour shirt when she could and generally left me stupidly distracted and feeling even more dorky than I already did, and I was a supremely dorky thirteen-year-old. If Prince hadn’t directly sung about sex even once then maybe feelings would have been different but good lord, compared to what I’d already heard over the previous years, this was a door being kicked open by someone who made it seem like it was all pretty easy. Just like his guitar playing on ‘Let’s Go Crazy’’s solo or his swooning duet vamp on ‘Take Me With U’ or his “AAAOWAH!” bursts on ‘Baby I’m a Star’, it all seemed so easy and immediate, so instant – for him. Not for anyone else.

Part of learning more about music is, I suppose, seeing what came before and figuring out where something you like might have come from. If Purple Rain is no different in that regard it’s also really, really hard to see as anything other than sui generis, something that came out of the sky. That’s both patently silly in its own right, given the slew of albums he’d already released on his own or working with others, and in light of his own manifold inspirations, whether it was Joni, Jimi or Sly, to name only three of many. (I’d also say Kate except it was Hounds Of Love that blew his mind and that appeared a year later, when he probably thought she was the only person on his level as a result – not a bad judgment.) Yet the net effect on Purple Rain seen from within its own sphere is almost to reduce a lot of things which had already happened down to being John the Baptist flashes waiting for a messiah. (You can’t exactly avoid that comparison point given ‘I Would Die 4 U’. I didn’t even realise this track was outrageous when it came out as a single. But it made an excellent fourth single, after ‘When Doves Cry’, ‘Let’s Go Crazy’ and ‘Purple Rain’ had stomped all before it. This meant that a song in which Prince claimed to be an omnisexual divine being was received with the thought, “Well yeah, why wouldn’t he be?”)

Everything was just so PRINCE on the album, no matter the band co-credits and the songwriting, arranging and engineering help (and a big hand here for Susan Rogers, engineer of engineers and just beginning her association with him which would last for nearly the rest of the decade). It was more like whatever had come before was heading in an accelerating speed towards his event horizon, song for song. Soul bent towards him, new wave angled again his direction, electronics existed to be programmed for and by him, confessional moments in song were his to clone, funk acted as his engine, hard rock and metal and more, sorry, the feedback was all his to use as needed. Hell, even backward masking to warp children’s minds served him here, except it was a spiritual call that the Lord was en route once again, beating even Bloom County’s joke about Deathtöngue going “Goooo to church…saaaaay your prayers” to the punch by three years. There was a time a couple of years before Purple Rain when it seemed like he and Rick James were challenging each other but the net effect of history was that by the time Dave Chappelle made fun of both only one was the truly sad punchline, and Rick had Street Songs but he never had this.

So, how to conclude. Well, do some looking around online – one version is here for now, it might not be later – for a particular clip, a performance of ‘Baby I’m a Star’ from the 1985 Grammys. (And just like that Solid Gold performance there’s another host trying to do some introducing over the screams – the host in this case being Wendy’s father. It doubtless helped a little in both directions that he ran the organisation who awards the Grammys.) It’s not technically perfect on the one hand – the clip itself, depending on the source, may be a little pixelated, and on the original broadcast Prince has a little mic trouble here and there. But this is a coronation moment of moments, before anything and everything changes as it must, before Around The World In A Day was both simultaneously brilliant and clearly not Purple Rain Pt. 2. Less than ten years after being the random wunderkind signed out of Minneapolis, king of the world; I was enthralled upon original broadcast and I’d rank it still as one of the top performances of all time. And what’s clear, too, is that he incorporates the past to a T – the way he and the band rework the song, synchronise their moves, his sliding mic catches, how dancers appear and he’s right there with them, it’s a James Brown tribute, it’s a Motown revue, all that just to start with and a whole lot more – and it’s all, again, him and only him as the guy who can pull it off and put all the pieces together, the lace and flowers and chiffon and frills. After the song is ‘supposed’ to have ended vis-a-vis the album version, everything just keeps going, call and response with the crowd about ‘wanting more’ and more is what happens. “Sheila E!” he calls as the dancers start grabbing people from the audience and the percussion fires up some more, the saxophone is exultant, the stage is packed, and so of course he disappears into his own band setup to play keyboards and sing for a bit, even as his none-more-ruffled/New Romantic-than-thou shirt almost fully falls off. He stands in front of everyone directing the whole thing like he was Leonard Bernstein and Bob Fosse, he spins and kisses, he points and shakes, then he just finally strips off his shirt as he almost – almost – casually walks up the centre aisle as everything is still going, bodyguard and some entourage members following, fists in the air, Muhammad Ali winning it ALL.

Yeah, I was wrong at the start. Not just one gilded lily for each of you. A whole damn bouquet.