Why did Prince build a world around the numbers 2 and 4, the letter U, and shades of pink and purple – and why did we never tire of it? How did such a specific mythology – of twinkling signs, jewels and pictograms – come to seem archetypal, even universal? In anyone else′s hands, the preoccupation with hot, carnal colours and magic numbers might suggest a dippy mysticism, but with Prince, each figure took on the force and charge of a love-symbol.

More than any other contemporary musician, Prince had the poet′s desire to retrain language, turning it into his own personal hieroglyphics: each phrase popping with eyes and signs, no line lying flat. Words had to be re-coded before they could enter his universe: customised with idiosyncratic spellings, abbreviations, and the maximum amount of innuendo. This is the nature of Prince′s ″alphabet street″ – a city flashing with letters, numbers and neon colours, the brightest signs reserved for female names and erotic passwords. It was a vision sketched out in impossible detail, inhabited so fully it had the power to seize the public imagination.

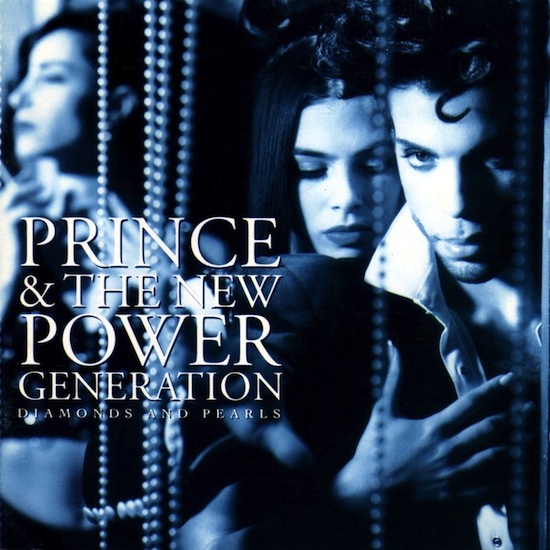

It′s in this context that we come to Diamonds And Pearls, Prince′s thirteenth studio album and his first with the New Power Generation. Released in 1991 to middling reviews (by Prince standards) and accusations of pandering for commercial success, it remains one of his most enigmatic works: anti-materialist yet strangely attracted to bling, decadent but with striking moments of purity, flirting with multiple sexualities while insisting that a ″woman be a woman and a man be a man″. It twists with contradictions, not least of them the signature Prince persona: the courtly horndog, by turns lewd and romantic. As a self-confessed mental tease (the following year, in ′Sexy MF′, he′d promise that the deepest fuck would involve ″not cha body your mind U fool″), Prince is adept at moving between spirituality and obscenity, often positioning the listener as the shameless source of his temptation.

For some critics, Diamonds and Pearls′ focus on love and sex verged on treacly – NME referred to the title track as ″pure pop shlock″, while David Browne mocked the use of double entendres as the ploys of an ″old uncle″. But, 25 years later, this album absolutely retains its mystique, complicating desire with the coy turns of a metaphysical poet, balancing intensity with a mischievous humour. Each song is elusive, shifting between levels of passion and irony. Even the album′s biggest romp, ′Gett Off′, is remarkable for its fastidious delicacy and politeness, alternated with menace. The irresistible ′Cream′ is almost a spoof of a hit, a rock song comically reduced to minimal components: the riff, the breakdown, the killer line. The title ballad remains a paradox – ostensibly a declaration of open-hearted love, yet weirdly cagey about gender and identity.

While promoting the record, Prince travelled with two lustrous girls he christened Pearl and Diamond: they were slinky black-clad attendants, their presence faintly ridiculous yet awe-inspiring. Remember that this was a time when a pop star′s sexual netherworld could seem wildly glamorous: we wanted glimpses of the carnivalesque life behind the curtains. Think of Madonna’s androgynous entourage, and the way they filled the corridors with power and eros in ′Justify My Love′ (1990). Today, Prince′s harem would be relentlessly parodied and exhausted of mystery, but in 1991, the idea of a sexual empire still carried a lot of currency.

′Gett Off′ is set in this type of dream-world: in the video, we descend into a realm of writhing bodies and sizzling guitar riffs. Musically, the entry to an underworld is signalled by a piercing shriek – one of Prince′s extraordinarily precise squeals and yelps, more expressive than any lyric. He moves over to address the newcomer, beginning with a gallant conceit: ″How can I put this in a way so as not to offend or unnerve?″ Pretending that unnerving isn′t the object of his game, he feigns a moral quandary: ″It′s hard 4 me 2 say what′s right / When all I wanna do is wrong″. This carefully worded preface has the effect of softening us up, appealing to the finer feelings as a prelude to outrageous sex. It′s typical of Prince to draw us into a silky comfort zone (offering to be our best girlfriend, whipping up a cashmere coat), so that any graphic statement comes across as an alarming jolt (″I clocked the jizz″, ″Now move your big ass ′round this way″). As with the most gifted singer-songwriters, Prince′s narration contains multiple voices – and we can never be sure who is speaking at any given moment. Is he the mindfuck you can′t take seriously? Is he the man of faith, capable of being genuinely wounded?

′Gett Off′ showcases Prince′s ability to slide in and out of personalities: the chorus alone contains several switches of perspective. After the repetition of ″gett off″, we hear four proclamations. First is a direct come-on (″23 positions in a 1 night stand″), characteristically tied to a lucky number: 23 acts, just short of one per hour. The second (″I′ll only call you after if you say I can″) is a return to the exaggerated chivalry of the start, asking for permission in minor matters while seizing control elsewhere. The third (″Let a woman be a woman and a man be a man″) seems oddly didactic, since virility and androgyny have never been in opposition for Prince. However, since gender roles are a form of cosplay for this artist, perhaps the instruction applies only to tonight: ″let a man be a man″, just this once. The fourth seems to reverse the previous wish, putting the woman in the driver′s seat (″If U want 2, baby here I am″).

The fact that the chorus offers four contrasting points of view while maintaining a singular erotic focus shows the complexity of the Prince persona: his tendency to shuck off his stated opinions, quickly moving to a new framing. The lyrics here insist on a separation between genders, but proceed to confuse that distinction. The artist plays shape-shifting genie, transforming himself to tantalise each stranger. ′Gett Off′ juggles a number of moods: leering innuendo, refined courtship, dream-like repetitions. Introducing a woman to the comforts of his home, he then taunts her for the tightness of her dress (″I heard the rip when U sat down″), triggering the same shriek which opens the track.

The tone becomes even stranger when Prince suggests that the listener is the one responsible for his visions. According to ″a friend of yours named Vanessa″, you invented a fantasy ″about a little box with a mirror and a tongue inside″ which got him excited: therefore, it′s your dirty mind which is driving the narrative. There are many layers of voyeurism here: the tale passed from a friend of a friend, the mirror as a multiplier of perspective, the box′s ability to arouse someone from a distance. This box of secrets will pop up again, David Lynch-style, in subsequent tracks; in ′Insatiable′, the singer offers himself to a camera-toting lady (″And I belong to 2 U and your little video box″), and hilariously attributes all his actions to her (″U say U want my hips up in the air?″). Prince often assigns bizarrely specific scenarios to the listener – not just the 23 positions of ′Gett Off″, but stories, images, and the ″nasty″ imagination which infects his own.

If contradiction is the hallmark of this album, then one of its central dilemmas revolves around wealth. Both ′Diamonds and Pearls′ and ′Money Don′t Matter 2 Night′ claim that riches are meaningless, then go on to assert the value of both. The former is peculiarly unresolved when it comes to both money and gender: the singer dangles the offer of jewels, admiring their beauty and sheen, before admitting that he doesn′t own them (″If I gave U diamonds and pearls / Would you be a happy boy or a girl″). A gold-digger won′t get anywhere with him, since he doesn′t have any money – but if he did, would it please her? For a song about disinterested love, the lyrics spend a lot of time praising all that glitters, including an entire section which spells out the word ″diamond″, as if studding gems into a bracelet. The singer is above materialism, yet the entire album seems to luxuriate in glossy, high-end production, from recording to marketing. It is these paradoxes which make the song memorable, complicating imagery which might otherwise seem hackneyed (the flawless jewel, the perfect lover).

That contrast between sincerity and impersonality is heard in the other notable line of the chorus: ″Would you be a happy boy or a girl″. Why the vagueness surrounding gender, the need to stipulate that there are at least two options available? A wordsmith like Prince doesn′t need to delay ″girl″ to rhyme with ″pearl″, so we wonder why a fervent declaration of love should be made to no-one in particular. The song advocates pure emotion, but is indifferent about where it might be directed. Although ′Gett Off′ was very clearly sung to a woman; this track seems determined to leave the door open. It is an odd, almost generic, way of expressing inclusivity, reflecting the combination of passion and distraction often found in Prince. Even with a song that seems to deal in traditional melodies and themes, he adds just enough ambiguity to avoid cliché.

The title track, like most of the record, is sung by a man who disdains greed yet can′t resist the sparkling signs of wealth (diamonds and pearls also refer to the trophy girls on his arm). Prince has always been enchanted by colour and luminosity – as evidenced by the album′s holographic cover, which shows a rainbow blur of movement. Colour is such a significant part of the Prince legacy: an expression of his maximalism and his disinterest in conventional notions of class. One can hardly imagine him dedicating a song to tasteful shades of green or grey: his music is filled with tacky paintbox colours (scarlet, pink, raspberry red), the kind associated with new money. Western culture tends to laud the subtle, tone-controlled masterpiece, but what Prince generally prefers is a ″hot mess″ of a song – simmering with changing moods and affects.

By these standards, ′Cream′ is an immense work of restraint – it′s Prince doing classic rock in quotes, opting for a neutral instead of his usual palette of electric hues. Like its later counterpart ′Peach′ (1993), ′Cream′ is a little slip of a song: a monochrome sketch compared to the rest of his oeuvre. It is breathtakingly clean and concise, introducing each element with cut-out precision, as if to say: here′s your basic beat, here′s the classic riff, here′s where you boogie down. There is lush imagery but it is lyrically sparse (″Cream / Get on top / Cream / You will cop″). The throwaway rhymes act as placeholders, their clipped endings (″cop″, ″stop″) making each line sound even shorter. ′Cream′ delivers voluptuousness in small, exact doses: as Prince has said, ″my bassist, Sonny T, can really play a girl′s measurements on his instrument and make you see them. I love the idea of visual sounds.″ T′s bass could give oozing emphasis to the most vanilla lyrics: here, it adds curve and contour to the pared-down words. This is Prince offering up supreme simplicity on a plate: the deconstructed rock tropes, the minimal lyrics spliced with layers of cream.

While ′Cream′ is a streamlined workout, the album′s most emotionally invested track is another atypical number for Prince: the beautiful, bleak ′Money Don′t Matter 2 Night′. Its opening chords and Rosie Gaines′ harmonies immediately steep us in the blues, preparing us for a tale of the city: a washed-up gambler embarks on scheme after scheme, ruining his family in the process. The title is more than a simplistic rejection of materialism, since it′s also the refrain used by the deadbeat husband; in the end, having no ″respect 4 money″ is as bad as an obsession with it. However, despite the lyrics, the song musically expresses both sympathy and ambivalence: the bass maintains the feeling of pressure while a caressing guitar offers moments of relief. Pre-chorus we hit a pause before pulling up for another iteration of ″money don′t matter 2 night″, a reflection of the gambler′s resignation and the slow drain of willpower. What′s remarkable is the way that Prince can convey inertia in his vocals and guitar-playing: the struggle to pick up a new line tells us that this is an old story with an inevitable finish. His final, gentle ″2 night″ is less a peaceful ending than a premature dimming of the lights.

The album′s closer, ′Live 4 Love′, envisions the singer as a fighter pilot under siege: performing countdowns, dropping bombs, navigating a firestorm. As he prepares to crash and burn, he reflects on his life and the city beneath him, accompanied by a soundtrack of robotic voices and references to ″Alpha 7″. Only Prince could make this blend of campy sci-fi and social realism so compelling – as always, his mixed metaphors show a desire to wiggle out of his own statements. The song title turns out to be ambiguous, an easy platitude as well as a heartfelt conviction. He serenely intones ″live 4 love″ while Tony M performs a muscular rap (there is room for every variation in Prince′s spectrum of male sexuality). Facing death, the pilot concludes that love is all-important – even though he makes sure to drop every last bomb! This is a very clouded epiphany: ″live 4 love″ is a mantra which loses meaning through repetition in the chorus. Most of the song′s energy is in the verses, which are busily populated with characters, codes and figures – those talismanic numbers which offer handholds on the way down.

These are two aspects of Prince: the single-minded believer versus the man who can′t resist throwing out red herrings, digressions, fantastic images. His sleeve art for the 12″ promo of ′Gett Off′ is a mass of signs, messages and impish scrawls: the work of a clowning, Picasso-like genius. A dedication appears in mirror-writing (apt for a mind which naturally thinks in reverse associations), inviting those who share a birthdate, a female acquaintance and a certain sensibility to join him. He salutes ″the power & the glory, forever″, but ″amen″ is replaced with a monumental ″GETT OFF″, its O turned into a peace sign: the emblem of a holy fuck. The entire record is said to be ″produced and mixed in your mind″, which is clearly the most fertile place for Prince to play, with his penchant for spicing seduction with real love, interrupting a prayer with a quip.

Although its deluxe sound made it critically unpopular at the time, Diamonds And Pearls has a blend of austere and over-the-top which truly characterises Prince. Flash and fanciness were integral to his work: the impulse to decorate classical structures with puns, curlicues, showstoppers. As we can hear in ′Cream′ and the title track, Prince′s version of conventional is madly inventive by anyone else′s standards, at once glitzy and restrained. Ultimately, the love for jewels and beauty was about that fantasy: of spiritual perfection which happens to come in a dazzling package.