Never meet your heroes – they’ll only be a disappointment. That the advice from sages through the ages. Well, two years ago I met one of my heroes and it was fucking brilliant.

The encounter took place on a crisp winter’s morning. I sat nervously at a bar on the eleventh floor of a London hotel waiting for Charles Thompson IV, or Black Francis as I knew him, who was promoting a new solo album. On arrival, the Pixies frontman grabbed me by the hand and planted a double-kiss on my cheeks – there was a lot of stubble-on-stubble contact. He then apologised for being late (he was ten minutes early) but said he’d nipped out to find a decaffeinated double espresso. In a moment of bold stupidity I enquired as to why anyone would want such a pointless drink; he noted my grin and said that he "liked the taste of bitterness in the morning".

What then unfolded was a perfectly blissful hour in my mundane existence. Charles chatted about vaginas (in hushed tones so as to not offend the breakfasting business-types) as his new album was dedicated to his "love" of them (the subsequent article I wrote for an Irish magazine was predictably entitled ‘The Vagina Monologue’) and he told me the Pixies were "not a band anymore, more of a big, long encore performance".

I watch him as he talked and desperately tried to suppress my inner fan-boy. He was interesting – and seemed interested in me – and I was mesmerized by his huge forearms. As he spoke, I realised that this unassuming man had written several of my favourite ever songs, created my very favourite album (Surfer Rosa) and given me one of my greatest gig experiences (on the Doolittle tour in 1989 at Leeds Polytechnic). Charles Thompson IV and his band had changed the way I thought about music and art. When I was 18, Pixies changed my life. And it was the song ‘Levitate Me’ that cemented the transformation.

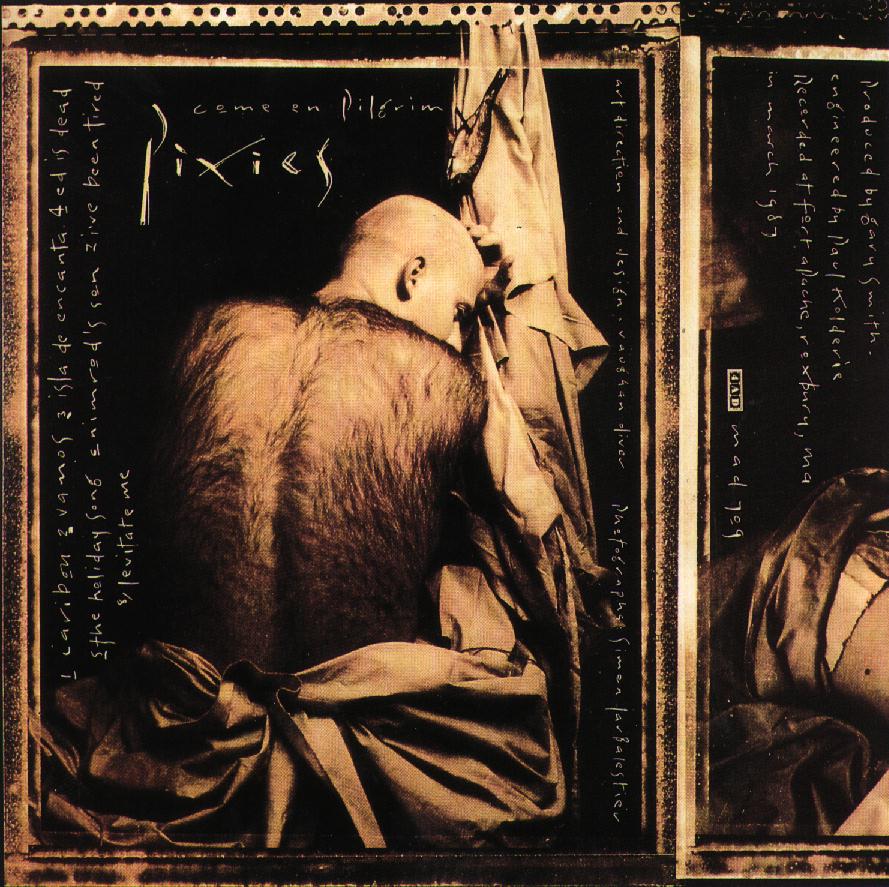

I first heard a version of ‘Levitate Me’ in Cheshire’s Dunham Massey Park in the spring of 1988. A loose acquaintance called Brian, who was a heroin addict (which was slightly frightening to me) and a vegetarian who’d eat chicken (which was highly confusing), sat below a huge oak tree strumming the song on an acoustic guitar. He actually sang the complex chorus rather beautifully, and a few days later I’d sourced a copy of Come On Pilgrim and instantly realised I’d found my new favourite band when I saw them astound an audience while supporting Throwing Muses in Manchester the following month.

It’s worth remembering just how astonishing it was to hear a Pixies record for the very first time. Come On Pilgrim contained pop songs, although the sublime melodies were concealed in gleefully visceral noise. It was beautiful and violent; there were songs sung in Spanish and others about whores, Lou Reed and levitation. One track spoke menacingly about the "son of incestuous union". The guitar playing was extraordinary and the lead singer possessed a guttural scream that seemed to be the actual sound of a man venting his spleen. With its eight songs covering barely 20 minutes, that first listen of Come On Pilgrim was utterly thrilling and encapsulated everything I wanted from music.

The sense of exhilaration was contagious. "When we started out there were all these young boys who were coming to see us and they really ‘owned’ us," Charles said to me during our interview, as I coaxed him into a bout of reminiscing. "We belonged to them and nobody else knew about us. The atmosphere was so charged. It was nuts. We couldn’t get into our van because people would be grabbing our clothing, not because we were pop idols, it was more of an [it which point he grabbed me by both arms, pulled his face close to mine and quietly let out one of his trademark screams] aaaarrrgh!"

However, the back story to all this excitement was reassuringly plain. The music heroes of my teenage years – Prince, Morrissey, Robert Smith and Adam Ant – had seemingly been beamed in from another planet. However, the four Pixies appeared like very regular folk. Ahead of the Leeds Polytechnic gig I spotted Black Francis in city’s Jumbo Records shop. He looked like any other student and certainly not like the lead singer in the world’s most thrilling rock band. And the creation of Come On Pilgrim was pretty straightforward – four people form a band, write some brilliant songs, record 17 of them in three days at a local studio. Wait for the world to notice. Job done.

Maybe it was a tad more complicated – the sonic shape of Come On Pilgrim was hugely influenced by Thompson’s initiation to music. Constantly moving between New England and California as a child, he would borrow albums from libraries – a process that reaped a penchant for Emerson, Lake and Palmer and religious artists such as Larry Norman (the title of Come On Pilgrim is taken from the lyric of a Norman song – "Come on, pilgrim, you know He love you") and ensured he only became familiar with "Hüsker Dü, Captain Beefheart, The Cars and Talking Heads" during his late teenage years. At college he met Joey Santiago who had begun to play guitar. The pair would jam together before Thompson spent some time in Puerto Rico as part of an exchange program where he became disillusioned with education. He decided to quit his schooling and would either travel to New Zealand to await the passing of Halley’s Comet or form a rock band. He wrote a letter to Santiago suggesting the latter.

The pair moved to Boston in 1985 and began writing songs. They placed an infamous advert in the Boston Phoenix newspaper seeking a bassist who liked "Hüsker Dü, Peter, Paul and Mary" while requesting "Please, no chops." Only one person replied – Kim Deal. Deal was from the smalltown America – Dayton in Ohio – and had been making music with her twin sister Kelley since their early teens. She met up with Thompson and Santiago and decided to join the band after hearing them play ‘The Holiday Song’. Deal’s ex-husband suggested a mutual friend, David Lovering, as a potential drummer. The line-up was complete – alchemy was about to unfold.

However, two other people would be pivotal in the creation of Come On Pilgrim – Gary Smith and Ivo Watts-Russell. Smith had started working as an engineer at Boston’s recently-opened Fort Apache studios. When the Pixies opened for his band, Lifeboat, a smitten Smith asked them to record at the Fort. The sessions would become the stuff of legend. Fuelled by (the highly-caffeinated) Jolt Cola, Pixies recorded 17 songs in three days in the freezing studio. Another three days of mixing would create The Purple Tape (christened because of the tape’s background tint) and would contain the eight songs that would eventually become Come On Pilgrim, while several of the remaining tracks would feature on each of the Pixies future studio albums. Smith remembered the sessions fondly, "There were so many songs and the band worked so fast – Charles was this clean, blonde-haired kid screaming at the top of his lungs," while Santiago recalled the experience as being "very primal".

While the Pixies had a set of songs, they stilled needed a record label. After a number of rebuffs (Deal kept all their rejection letters), Smith asked Throwing Muses manager Ken Goes to contact their British record label 4AD. The Muses were good friends with the Pixies and a hook-up with 4AD seemed logical. The label had been co-founded by Ivo Watts-Russell, who, on receiving The Purple Tape claims to have "adored it from day one" even if his first inclination was to not sign the band on account of them sounding "too rock & roll". He was quickly persuaded otherwise by his girlfriend.

However, Watts-Russell wouldn’t commit to releasing The Purple Tape in its entirety and suggested the list of eight songs that would feature on a mini-album (or maxi-EP depending on exact definitions). The choice lay solely with Watts-Russell; the rationale for the track-listing being that he felt "those eight songs were a bang in the face and left you wanting more."

And, by jiminy, he was right. Opener ‘Caribou’ descended from pop crooner into the carnage of a screeching finale, ‘Vamos’ showcased extraordinary guitar improvisation from the prodigious Santiago, while ‘Isla De Encanta – sung in Spanish, was 90 seconds of punk-pop perfection. ‘Ed Is Dead’ and ‘The Holiday Song’ perfectly epitomised the ‘pop-song-in-wolf’s-clothing’ concept at the core of the Pixies allure. Lyrically, Come On Pilgrim was spiced with darkness, death and illicit sex – ‘Nimrod’s Son’ spoke of "the son of a motherfucker," while the thrash of ‘I’ve Been Tired’ strained with sexual frustration. The album ended with the magnificent ‘Levitate Me’, a song rammed with drama that spiralled upwards and out of the sonic stratosphere.

Post Come On Pilgrim, the Pixies holed up with Steve Albini to record the mighty and, for me, peerless Surfer Rosa, their genius seemingly prepped and ready for lift-off.

Of the songs Watts-Russell discarded from ‘The Purple Tape’, three tracks (‘Break My Body’, ‘Broken Face’ and ‘I’m Amazed’) would be reworked for Surfer Rosa, while perhaps most tellingly, a revised version of the carnal ‘Subbacultcha’ would eventually see the light of day four years later on the Pixies’ final album, Trompe Le Monde. Arguably, ‘Subbacultcha’ was the best song on that record and its inclusion a transparent sign of waning powers.

A quarter of a century after their first release, there are aspects of the way Pixies are historically portrayed that royally piss me off. I hate the reductionist theory about them being the ‘quiet-loud’ band, as if that was the only song structure they had – it smacks of people who didn’t get past ‘Tame’ and ‘Gigantic’. And I really loathe how the anecdote about Kurt Cobain writing ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ in an attempt to sound like ‘Debaser’ became morphed into a ‘MTV-lite’ revisionist theory that somehow the Pixies’ biggest achievement was to act as a proto-band for Nirvana.

And, yes, I know I’m being hypersensitive, but when I spoke to him, the latter point was also a source of irritation to Thompson. "What I don’t appreciate, or give a shit about, is the whole ‘Kurt Cobain said that ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ was a homage [to us]," he told me, holding my gaze and making me feel somewhat uneasy. "That’s not a diss of Kurt Cobain, it’s just that it’s not what’s important – that some other rock musician liked us. No shit – we’re all a bunch of music geeks. What’s important is that for some 15-year-old kid, you changed his life. That’s the phenomenon."

Personally, I was nearer 18, but, on hearing Come On Pilgrim, I was one of those kids.