"They flutter behind you, your possible pasts".

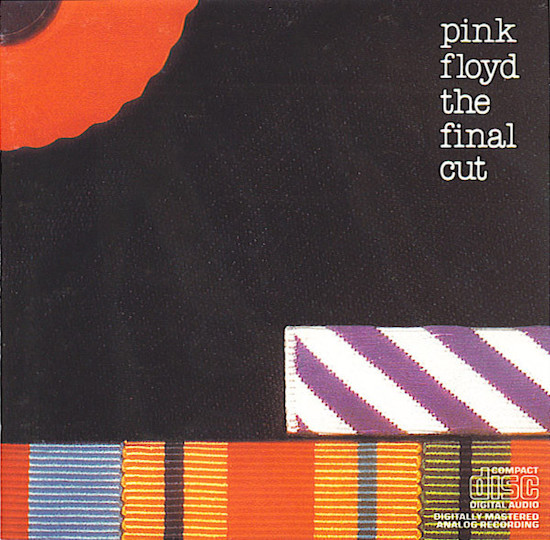

This seems the right place to start. 50 years out from The Dark Side Of The Moon, which milestone has been – justly – the subject of considerable hubbub, and 40 years on from The Final Cut, which, equally justly, has not.

A decade may bring little change in our present, glacial pop time. A mere two or three album cycles for a major global act, the last of which records will likely be at most cosmetically different from the first. Even in the 70s, ten pop years passed much more slowly than in the decade before, when pop culture come June could be all but unrecognisable from its manifestation in January. Still. From Dark Side to Final Cut is quite the shift. From one of the most perfectly balanced LPs ever created, to a torturous, lopsided salvo of musical pamphleteering. What happened? In short: Roger Waters did.

There are people who happen to you, sometimes like gifts from the universe, and sometimes like accidents, or afflictions, or disasters. These might even be the same person. When it comes to Pink Floyd and Roger Waters, that looks to be very much the case. Exactly the right man in the right place in 1973. Exactly the wrong one ten years later. The chief engineer of a schism – musical, philosophical, political – that reverberates to this day. It’s a faultline that over the last twelve months has cracked wider and more violently than ever as Waters has doubled down on his views about Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine (addressing the UN on behalf of Putin and saying that Ukraine is "not really a country at all". David Gilmour’s wife Polly Samson accused Waters of being, among a bouquet of withering denunciations, “antisemitic to [his] rotten core… a Putin apologist and a lying… hypocritical… misogynistic, sick-with-envy, megalomaniac"; Gilmour retweeted this, adding that “every word [is] demonstrably true”.) It’s a divide that matters far more than simply the division of a significant and beloved band, although that would be shame enough. Instead, it is one that exemplifies the profound chasm between worldviews that the war in Ukraine has brought into so sharp a focus.

It didn’t previously matter where you stood on the feud between Roger Waters and David Gilmour (which was, let’s face it, the most entertaining thing to happen in the last 40 years of Floydery; there isn’t that much shade on the dark side of the moon.) It does now, because of what each of them presently stands for in turn. You are either for defending democracy, sovereignty and self-determination against despotism, subjugation and revanchism, or you are against it. The idea of a peaceful middle way is a fantasy, because the despotic revanchists themselves have no interest in it. They will seize whatever they can get either by force, or by the threat of force; thus only force, or the threat of force, will stop them.

In 1942, at what nobody then knew to be the halfway point of the Second World War, George Orwell wrote that “Pacifism is objectively pro-Fascist. This is elementary common sense. If you hamper the war effort of one side you automatically help that of the other.” It is as true of today’s self-professed (and highly selective) pacifists as it was then. In a war of aggression, of imperial conquest, anything other than material support for the victim constitutes material support for the aggressor. That includes the fatuous proposition one go straight to the peace talks and leave out the war altogether. It is indeed, pace Harold Macmillan (paraphrasing Winston Churchill), better to jaw-jaw than to war-war. But not when it means hurling the innocent into the maw-maw of the belligerents, in the futile hope this will satisfy the latter’s appetite. There is a word for this. It’s called appeasement. It was most famously attempted by Neville Chamberlain at Munich in 1938, and what a resounding success that proved to be.

The odd thing, looking back, is how well those two records reflect each aspect of this divide. Dark Side was the first Pink Floyd album for which Waters wrote all the lyrics. Final Cut was the last. Dark Side is humane. It is compassionate. It is hurt, and distressed, by injustice. It is an album of open questions. Final Cut is an album didactically and furiously certain it knows every last one of the answers. It suggests the effect of ten years’ gradual immersion in a very particular school of politics that preys upon such hurt and distress – just as the unhinged pronouncements of which Waters lately delivers himself show what another four decades marinating in that toxic gumbo is liable to wreak.

Waters was, of course, the ideal candidate for such a weltanschauung: a seething cluster of issues in search of a valorising framework. Gilmour once described him as “one of the luckiest people in the world issuing a catalogue of abuse and bile against people who’d never done anything to him.” Gilmour was referring specifically to the concept and lyrics of The Wall (1979), and he wasn’t wrong there. But it also usefully describes one of those personality types that are magnetically drawn to, and thrive in, the politics of crankery. They include grandstanding would-be saviours fuelled by white-hot narcissistic rage. Relentless cry-bullies projecting their interior hellscape onto the world at large. Useful idiots who cannot encounter two evils without siding with the greater, and for whom no crime is more unspeakable than declining to take them at their own estimation. If you want to understand politics in general, and crank politics (of any stripe, it should be noted) in particular, don’t start by reading up on politics. Start by reading up on psychology.

By their causes shall ye know them, for these tend to come as a job lot. They are, by and large, people who loathe the West and attribute to it all evil, yet who rely entirely upon its freedoms and could not for one moment stand to live without privileges anywhere else. People who find reasons to indulge in apologism for Vladimir Putin, or Bashar Assad, or Joseph Stalin – and who would have you believe that our (deeply flawed, endlessly improvable) democracies are ethically and functionally no better than these. People who believe that nobody should ever take up arms to defend themselves – unless, of course, it is against the West. People whose emblematic organisation could be more accurately renamed Stop Some Wars; their guiding creed, Anti-Imperialism (No, Not That One, Nor That One, Either.) People who have now, as Waters has done, shown the world exactly who they are over Ukraine. A real Naked Lunch moment, when everyone sees what’s on the end of every fork – except for Waters and company, who can no more perceive it than a budgie can recognise its reflection. Or perhaps, if you are of a left-wing inclination, it serves as a Kronstadt Moment: one to stop and ask yourself just what kind of leftist you wish to be.

Because, above all, what we might call the Crank Left is characterised by a kind of religiosity: a conviction that it is the One True Left, that there is no other leftism. A Left viewpoint that is essentially unromantic, rational and pragmatic has zero appeal to the Waters of the world: how can you be the Main Character in it? In order to achieve your professed aims, or at least some of them, you might need to sacrifice the identity you have forged, and that would never do. It’s here that the interaction of politics and pop becomes markedly fraught, because Main Characters tend to be vital in pop and – as the last few years of British national life, across the board, demonstrate only too vividly – calamitous in politics. Yet the curious thing about Waters is that when he wrote the lyrics for Dark Side, there was no such solipsism entailed. By his own account, he was writing for the first time about other people. Dark Side was, he said in 2003, motivated by empathy. We should believe him. It rings true, just as the album itself does. He added, “It always amazes me that I got away with it because it was so sort of Lower Sixth.” Which is one those occasions when somebody sounds both a hair’s breadth, and a million miles, from self-knowledge. There were callow moments on Dark Side, true, but also resonant and succinct bits of lyric-writing, most famously:

"Hanging on in quiet desperation is the English way"

which is as eloquent a summary of the immediate post-war years as anyone has managed in as many words. Or this faultless turn of phrase :

"The lunatics are in my hall

The paper holds their folded faces to the floor

And every day the paperboy brings more"

nailing in three graceful lines what Waters would ten years later devote an entire crashingly awful song, ‘The Fletcher Memorial Home’, to flailing at hopelessly. Waters could not understand that his first noteworthy foray into lyric writing was much his best. The truly dreadful sixth-form stuff was to follow, and he was evidently proud of it.

Yet there are moments on The Final Cut with similar potential. They occur almost entirely within two songs. That line on ‘Your Posssible Pasts’, fluttering like the banners and ribbons of war commemorations – how much better an opening that would have been to the album than the clumsy, histrionic ‘The Post War Dream’. And how much better the song itself would be if it allowed its fragility, and Waters’ genuine sensitivity towards his subject, to carry the day, rather than punctuating it (as is the pattern throughout the record) with agonised, tooth-grinding crescendos. Some of the greatest artists have no filter, no self-editing mode, no way of discerning what is good and bad about their own work (Neil Young comes to mind), and if they did, they wouldn’t be half the artist they are. But none of them routinely sabotage their own best songs that way. Waters does, and that failing has kept him from individual greatness. The Final Cut shows what happens when nobody’s there to stop him, either because they’ve left, or because they just can’t be fucking bothered to fight him any longer.

Take by far the strongest song on the album, ‘The Gunner’s Dream’, which underlines just what a poignant and persuasive thing this might have been throughout had Waters any artistic judgment, or any faith in that of his bandmates. It describes what we take to be a memorial service that includes his father, killed in the war, the defining event and trauma in Waters’ life. He links this compellingly to a Thatcherite betrayal of the social compact – the titular “dream” of a better life for ordinary people – for which he believes his father was sacrificed. We should remember that Waters’ father was a conscientious objector who changed his mind and signed up, dying in the Battle Of Anzio in 1944. Even if one thinks Waters mistaken about pacifism, it is no abstract matter to him. But you don’t need to know that to shiver at these lines, and his delivery of them. They are close to heartbreaking.

"Goodbye, Max

Goodbye, Ma

After the service, when you’re walking slowly to the car

And the silver in her hair shines in the cold November air

You hear the tolling bell

And touch the silk in your lapel

And as the tear drops rise to meet the comfort of the band

You take her frail hand

And hold on to the dream"

Again, how much better this song would be without its keening, gurning climactic passages. The Final Cut has the bones of a fine album with the sagging flesh of a poor one pressed onto them like clabber. It gave us the clearest sign yet of Waters’ assimilation into Dave Spart-ism, never more so than on ‘Not Now John’, a quasi-reprise of the leaden disco-rock of ‘Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2’. This is a lumbering, de haut en bas, wake-up-sheeple polemic about the false consciousness of The Workers.

One shouldn’t expect artists to share one’s politics or worldview. Nor is that my grievance here – or at least, not so far as the art goes. Plenty of artists with terrible opinions have made great art, and some have made great art out of terrible opinions. Moreover, artists who do share my worldview often make art that is amiaby dull. An album is not an essay, nor should it be. The trouble with Waters is, the worse his ideas became, the worse the art became too. The Final Cut is often described as a de facto solo Waters album, but that is to do it a disservice; for all its faults, it’s nowhere near as bad as that. Waters’ actual solo catalogue is nigh-on unlistenable in every regard. What matters most about Waters is his deployment of his fame, not his art, to promote his rotten ideas. As for separating the artist from the art, well, the question is less whether one should – that is entirely the individual listener’s own business – and more whether one can.

In a display of Main Character Syndrome so outlandish I originally took reports of it to be a spoof, Waters recently announced he has re-recorded The Dark Side of the Moon as a solo project – perhaps the least necessary and eagerly anticipated venture not only of his own career, which has included a few, but of anybody’s. “They can’t write songs,” he says of his ex-bandmates, “they’ve nothing to say. They are not artists! They have no ideas, not a single one between them. They never have had, and that drives them crazy.”

As is standard practice for conspiracist crackpots and blithering egomaniacs, Waters is deploying a half-truth in the service of a grotesque falsehood. The other Floyd members have consistently acknowledged the importance of Waters’ lyrics and vision. The output of the Gilmour-led Floyd is indeed glossy and hollow, the form of the thing without the soul of the thing. But, not artists? Waters’ songwriting is celebrated solely because of what Pink Floyd made of it. Nothing he has done without them possesses the remotest merit. Having “something to say” does not necessarily make it worth saying; nor does it make the way you say it worth hearing. Projection is a familiar defensive mechanism among grandiose narcissists. Just who is being driven crazy here: his relatively even-tempered bandmates, or the man who knows that only the most rabid fans have the slightest interest in his post-Floyd work? That his only true and immaculate masterpiece is also David Gilmour’s masterpiece, and Nick Mason’s, and engineer Alan Parsons’, and – especially, with his jazz chords, exquisite atmospherics and tempered touch – the late Richard Wright’s, the understated keyboard master whom Waters manoeuvered out of the band. Dark Side was a collective triumph, never to be matched or repeated, and Final Cut makes it painfully obvious as to the principal reason why. Dark Side’s famous prism cover comes to seem a symbol of what happened thereafter: the whole light refracting into its component parts, each on a different wavelength. You wonder at a counterfactual band history in which Waters were able to distinguish between leadership and control-freakery.

Imagine knowing, on some deeply buried level, what a tour-de-force The Final Cut might have been had the band you’re in kept playing the same tune. Imagine knowing how far it falls short. Imagine knowing that nobody, yourself included, ever sang or ever will sing your words as thrillingly as the former comrades you despise. Imagine the psychic noise you have to make to blot out such thoughts from ever consciously entering your own head. It must resemble the Pink Floyd scream, a sonic motif that recurs from the late Sixities onwards. Roger Waters makes it very, very difficult indeed to feel sorry for him – and anyway, he makes up for it on his own account – but there are moments, flickers, when you look at this squalid mess of a man and of an artist, at the abyss between what he could have been and what he is, and the impulse you register, overcoming even mockery and revulsion, is pity. Roger, you’re nearly a laugh, but you’re really a cry.