Philip K Dick (1928-1982), was the author of over 40 novels and 121 short stories, many of which inspired innumerable influential science-fiction films both in name and unacknowledged debt. Most famously Blade Runner and Total Recall, but also indirectly, the likes of The Matrix and Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind.

Initially desirous of literary recognition, Dick penned nine mainstream realistic novels from the early to the late 50s, whilst simultaneously publishing a steady stream of science-fiction stories in pulp magazines. Though very much of their time, all of Dick’s mainstream novels are worthy of investigation, but it is for his wild speculative ideas, questing philosophical mind and essential humanity that Dick is best remembered.

Authentic adaptations of his novels have been few and far between, and it could be argued, as in the case of Richard Linklater’s A Scanner Darkly, less successful. Nonetheless, Dick’s main explorative notion – investigating what constitutes reality – combined with his prolific writing practice, spawned so many ideas that his presence is still felt, more than any other writer in the landscape of contemporary science-fiction.

Blade Runner might be a substantially different film from the novel that inspired it, but the principal philosophical notion driving Ridley Scott’s classic tale is pure PKD. The Voight-Kampff test seeks to assess whether an individual is a replicant or not, but for Dick, for whom the defining characteristic of humanity was empathy, the possibility exists that artificial lifeforms may retain the potential to be kinder than us damaged human beings.

Total Recall takes its inspiration from the short story, ‘We Can Remember It For You Wholesale’, and runs with it for almost two hours. If Dick’s novels appear almost too full of ideas to be successfully translated straight to film, his experimental attitude towards the notions that he cultivated, covering non-linearity in time travel, quantum inspired logic, and experimental drug therapy (to name but a few), proliferate so much in contemporary culture, that even those who haven’t read any of his books are likely to have been touched by ideas that he originated.

His influence was strongly felt among many musicians too. Sonic Youth’s Sister took inspiration from his work, as did Gary Numan. The Mr Bungle song ‘None Of Them Knew They Were Robots’ from their California album contains references to Dick’s philosophical exegesis, such as: ‘In the black iron prison of St. Augustine’s light’.

Dick was a prolific writer who often composed his books fuelled by amphetamines and on the fly. There are some who feel the quality of his prose is lacking and the sometimes non-linearity of his plot elements a step too far. There are those who believe that Dick’s oft discussed ‘mystical visions‘ were simply the product of his drug addictions and troubled psyche. There are also many who believe, as do I, that Dick was the closest thing we have to a genuine seer or shaman of his era, and that his life took an incremental series of steps towards that direction from its onset.

Whilst it may be the case that Dick was less concerned with being a prose stylist than many of his contemporaries, the consistently high quality of his inventiveness and imagination puts many of those contemporaries to shame. The impromptu nature of his compositional process may be at the root of the complaints some have about his prose style, but it is also the driving force behind his abundant creation of ideas and the almost Zen-like desire to transcend the either/or trap of language itself.

Quotes one could offer in support of such an argument are plentiful, but for starters consider how relevant this sounds today: “There will come a time when it isn’t ‘They’re spying on me through my phone’ anymore. Eventually it will be ‘My phone is spying on me.’” Consider also, the answer that Dick provided to the question, ‘Which side of the cold pack are we on?’, which recurs in several of his novels, including 1969s Ubik and in a slightly different form, in 1964s Three Stigmata Of Palmer Eldritch. In the interests of not spoiling those books for anyone who as yet hasn’t read them, I’ll not give that answer in any simple form here. Suffice to say, the endings of both those two books provide a jolting realisation that the either/or terms of Aristotelian logic may not be as absolute as we once thought.

Born alongside his ill-fated twin, Jane, in December of 1928, Philip Kindred (a ‘kindred’ spirit being one that shares a mutual meaningful connection) Dick’s profound sense of guilt at his having survived at her expense, combined with a naturally philosophical turn of mind, gave him a kind of connection to the ‘world of the dead’ that was not dissimilar to the spirit link shaman claim to experience. The pair were born prematurely, and with his mother not providing enough milk for them both, PKD later appeared to believe that he had taken sustenance that should have instead been given to his sister.

The trauma of her death remained at the heart of Dick’s inner life, providing many resonances within his fiction, including Edie Keller’s conjoined twin brother in 1965s Dr. Bloodmoney, Or How We Got Along After The Bomb, which in turn undoubtedly influenced the character of the mutant Kuato in Paul Verhoeven’s film, Total Recall. As a young boy, the writer was beset by fears such as agoraphobia, problems with eating in public, and intermittent asthma attacks, for which he was prescribed aphedrine, a type of amphetamine. An early incident from his third-grade year provided a sense of enlightenment that shaped the empathic intelligence Dick later utilised so successfully in his writing. The young Phil was tormenting a beetle that had hidden in a snail shell. As Lawrence Sutin relates in his PKD biography, Divine Invasions:

"He came out, and all of a sudden I realized – it was total satori, just infinite, that this beetle was like I was. He wanted to live just like I was, and I was hurting him. For a moment I was that beetle. Immediately I was different. I was never the same again."

There has also been speculation that Dick was sexually abused by a family member, perhaps his grandfather, a theory touched upon in Sutin’s book and further extrapolated by biographer Gregg Rickman. Whatever the truth to that claim, it is clear that Dick’s life was lived under persistent psychological pressure and that his writing enabled him to articulate and in some cases, spiritually transcend, those difficulties.

Before sitting down to write this piece, I re-watched most of Philip K Dick: A Day In The Afterlife. As is often the case with such posthumous documentaries, the effort to evoke a deceased artist’s essence via an ongoing sequence of talking heads vignettes is less than satisfactory. If we were to judge what it was like to be Philip K Dick from the recollections of individuals such as his third wife, Anne, it would be a depressing affair largely devoid of inspirational moments. Of course, individuals are comprised of many multifaceted elements, and it is often said that a writer’s work is the ‘best of’ that person. Thankfully we have Dick’s wonderful writing to also remember him by.

Fast forwarding to February and March of 1974, Dick found himself living as though he were a character in one of his own science-fiction books. Undergoing a series of visions and revelations of an apparently reality altering nature, which he himself referred to as ‘2-3-74’, Dick fictionalised these experiences in his 1981 novel, Valis. He also attempted to provide a philosophical basis for them in his ongoing journal, extracts of which were eventually published as The Exegesis Of Philip K Dick.

According to the legend, whilst supposedly under the lingering influence of sodium pentothal following dental surgery, Dick answered his door and saw a dark haired girl wearing a Christian fish symbol around her neck. The symbol triggered a series of intense visions initiated by a flash of pink light. In the months that followed, Dick believed he was having information beamed into his head from some external source. He entertained various notions of who the sender of that information might have been – from the Russian secret service, to the extraterrestrial entity he theorised as the ‘Vast Active Living Intelligence System’ of Valis.

Whatever their source, the visions continued for a time, sometimes manifesting as philosophical ideas, sometimes forming images like abstract paintings or sophisticated engineering schematics. Dick believed that the tyrannical Roman Empire persisted in the guise of Nixon’s administration. So far, so crazy, you might say, but the visions weren’t completely comprised of paranoid, delusional material. Dick felt guided by their influence, and when a voice told him to seek medical attention for his infant son, he did so, allegedly discovering in the process that the boy had a potentially fatal inguinal hernia which was not observable by the naked eye, and for which he received life-saving surgical treatment.

There has been much speculation and disagreement surrounding the circumstances and nature of those experiences. There are many articles about Dick speculating on whether he was a mystic or a madman. A defining characteristic of schizophrenia is that the afflicted individual has a diminished capacity for abstract thought. A 1998 report by RW Heinrichs and KK Zakanis, Neurocognitive Deficit In Schizophrenia: A Quantitive Review Of The Evidence, states that: ‘Dysfunctions in working memory, attention, processing speed, visual and verbal learning with substantial deficit in reasoning, planning, abstract thinking and problem solving have been extensively documented in schizophrenia.’ To characterise Dick in such a fashion, at any point in his career, is clearly incorrect.

The fact that Dick never accepted one final psychological or ontological framework for his experiences, and would constantly be trying possible alternatives and reasonings aligns him more with ‘model agnostic’ thinkers such as Robert Anton Wilson. When Dick’s apartment was broken into on 17 November 1971, he speculated that perhaps he had hit upon some ‘hidden truth’ accidentally in one of his novels and the government was attempting to seize such material from his safe. He also refused to rule out the possibility that perhaps he had done it himself.

The frequency with which his visions and epiphanies intersected with his everyday life recalls Carl Jung, who in his autobiography, describes asking a friend for photographs of the vivid frescoes he had seen whilst visiting a church in rural Italy. His friend wrote back confirming that there were no frescoes, that he had in fact been ‘hallucinating.’ There are parallels too with the visions that John Lilly (whose fascinating life was the inspiration for Ken Russell’s Altered States) experienced under the influence of ketamine whilst in an isolation tank. Lilly prophesied a dramatic conflict between organic life and Solid State Intelligence – a developing computer network, way back in the late 70s.

Rather than viewing the events of ‘2-3-74’ as an anomaly in Dick’s life, it may be more useful to see them as a development of a process that had begun much earlier. There are many high points amongst Dick’s bibliography, but even relatively early entries, like 1955s Eye In The Sky, toy with weighty ideas, in this case alternative universes in the form of solipsistic worlds built out of an individual’s internal fears and prejudices, set against a McCarthy-like era of authoritarianism. 1963 Hugo Award winner, The Man In The HIgh Castle, which again is considerably different from the television series it inspired, depicts an alternative history in which the Nazis won WWII and rule over the former United States. The novel contains some of Dick’s most ‘literary’ writing and also adds a meta dimension in the form of novelist Hawthorne Abendsen, a Dick-like figure whose banned novel within the novel, The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, postulates the ‘truth’ that the Axis powers in fact won WWII.

Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep is a considerably more involved work than the film it inspired – Blade Runner. Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said, The Three Stigmata Of Palmer Eldritch, A Scanner Darkly, the Valis trilogy and even Radio Free Albemuth also have much to offer.

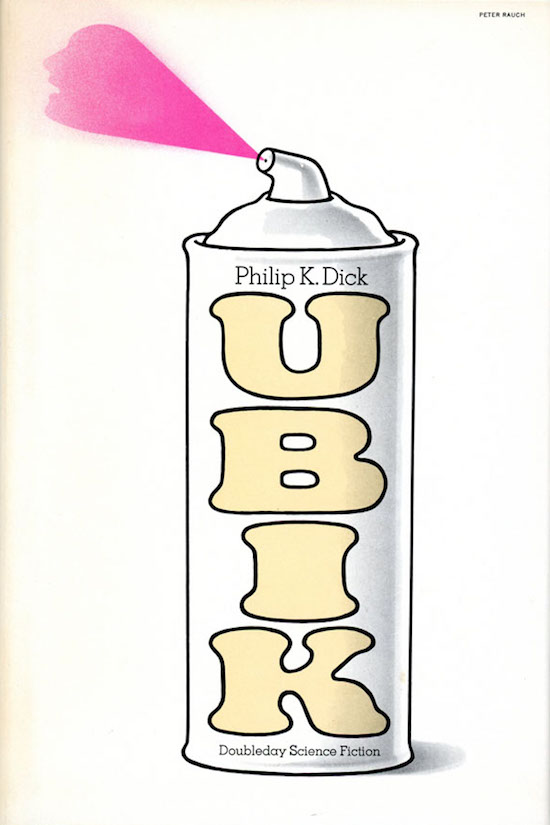

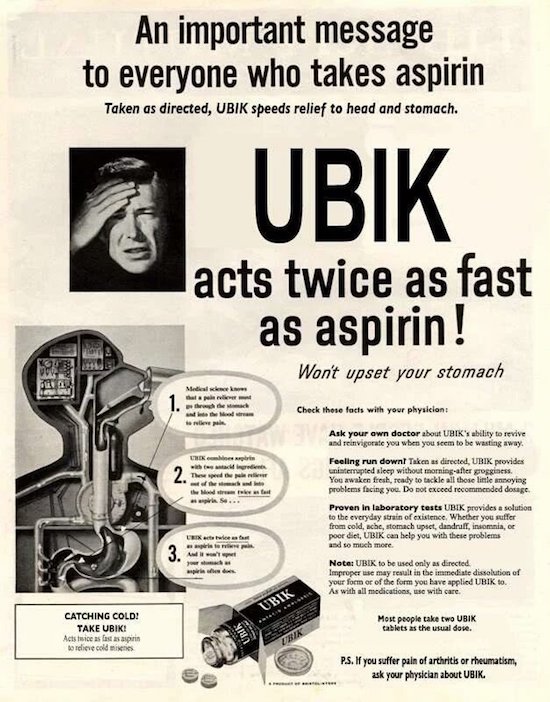

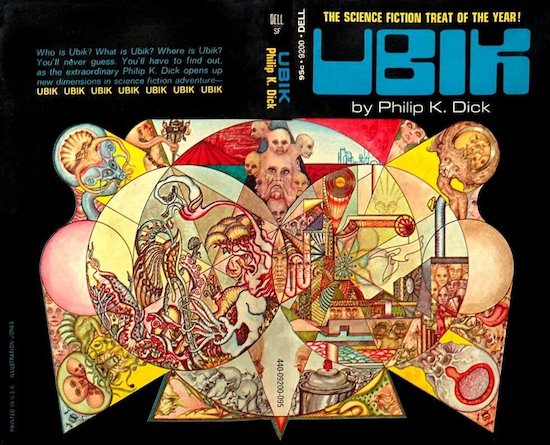

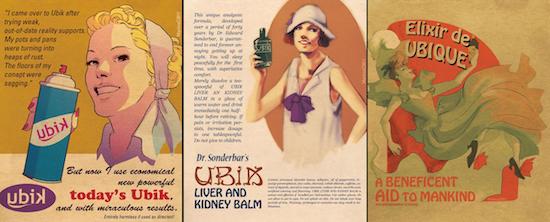

In 2005, Time magazine named Ubik, published in 1969, as one of the 100 best English-language novels published since 1923. Set in a future where psychic powers are commonplace, Joe Chip works for an anti-psychic agency who experiences disturbing changes to reality that can only be temporarily averted by the application of a enigmatic substance called Ubik. Dick places advertisements for Ubik at the start of each chapter, amusing asides at odds with the transcendental nature of the substance when we eventually discover its true nature:

"Pop tasty Ubik into your toaster, made only from fresh fruit and healthful all-vegetable shortening. Ubik makes breakfast a feast, puts zing into your thing! Safe when handled as directed."

Ubik, as it is later revealed, is nothing less than ‘god in a spray can’ – the only force capable of halting the onset of entropy in a universe that is really a kind of shared hallucination between individuals near to death, kept refrigerated so that they can interact with their still living loved ones, perhaps once a year. This being Philip K Dick of course, even this dire situation is not quite what it seems, and the question of ‘which side of the cold pack’ we are on, is driven home with the kind wild final twist worthy of a Zen master’s koan. The notion that reality is ‘holographic in nature’ – that we are all in a sense ‘brains in a tank’ experiencing some form of consensus hallucination – is something that Dick returned to again and again. It is an idea that is no longer a fringe theory and one whose currency has only increased amongst the scientific community in recent years.

Undoubtedly, the years since Philip K Dick’s death have been kinder to his legacy than the admittedly paranoid writer likely could have imagined. When considering the kind of man he was, it’s perhaps worth comparing him to another science-fiction writer from the time, one who actually saw himself as a mystic and who, despite his alleged negativity towards organised religion and psychotherapy, created a hugely successful pseudo-religion using the tools of psychotherapy for huge monetary gain – L Ron Hubbard. Both Hubbard’s writing ability and his powers of empathy, are severely impoverished when compared to those qualities Philip K Dick had in abundance. A lot of Scientologists may profess a sincere love for ‘LRH’, but one suspects that going against such sentiment would be extremely difficult, given the high level of financial investment anyone who spends any length of time in that organisation must make. Those who remember Philip K Dick fondly have no such financial interest spurring their emotional attachment to his writing.

Given the dark times we are currently living through, it’s difficult not to wonder what Dick would think if he were alive now. As he was a seer of such profound ability, it’s not hard to find possible answers to that question. Take for example, this quote from Radio Free Albemuth, which seems uncannily pertinent:

"There is no point in dwelling on the ethics of Ferris Fremont, time has already rendered its verdict, the verdict of the world. Except for the Soviet Union, which still holds him in great respect. That Fremont was in fact closely tied to Soviet intrigue in the United States, backed in fact by Soviet interests and his strategy framed by Soviet planners, is in dispute, but is nonetheless a fact. The soviets backed him, the right-wingers backed him, and finally just about everyone, in the absence of any other candidate, backed him."