In response to the Jamaican government’s refusal to allow Black Power supporter Dr Walter Rodney permission to re-enter Jamaica after his trip to a black writers conference in Montreal, The Rodney Riots began on the 16th October 1968.

Concerned about the effect this Guyanese civil rights thinker would have in Jamaica, the government declared Rodney, a lecturer in African History at the University of the West Indies, to be an undesirable person.

But the very move the government made "to save the nation" (as The Gleaner, a Jamaican daily broadsheet, put it) was the very thing that sparked chaos.

Taking part that day in the demonstrations and looting was one Winston Hubert McIntosh, known to most as Peter Tosh. He placed himself behind the wheel of a coach, drove it towards a local shopping precinct and rammed it through a glass storefront. All around him people piled in to loot what they could before climbing on board the coach as Tosh backed out and ferried them all back to Trench Town.

Both the police and army were dispatched to quell the violence that was spewing out onto the streets of Kingston, causing millions of dollars in property damage. People were killed and many were injured.

These random acts of violence and destruction had the government spooked. But scarier still was that protesting alongside Tosh and the Trench Town activists were middle class students. This was unprecedented. Between them they had been heard to chant slogans pertaining to Black Power, a movement that was causing ripples not just in Kingston, but across the world.

On the very morning that the Rodney Riots began, 1,500 miles away, African American athletes and Olympic medal winners Tommie Smith and John Carlos were to be seen giving the Black Power Salute as the U.S. anthem played at Mexico City’s Olympic Stadium.

This silent gesture was one of the strongest political statements in the history of the Games. It was not, however, a welcome gesture. The athletes were booed as they stood down from the podium and subsequently ejected from the US Olympic team.

Peter Tosh may have been imprudent in his method of protest, but all around him, signs pointed towards something indisputable. Things were not equal. They were not right.

The anger inside of Peter Tosh had been building for many years; as a child he was asked to sing at his local church a hymn that included the lyrics; “Lord wash me and I shall be whiter than snow.” He was nine years old and it filled him with disgust.

Personal, national and international events had conspired together to create anger and frustration within Tosh about these iniquities.

"The truth has been branded, outlawed and [made] illegal. It is dangerous to have the truth in your possession. You can be found guilty and sentenced to death."

Peter Tosh.

In 1977 Peter Tosh released Equal Rights, a rallying cry against what he called the ‘shitstem’, his declaration of rage against the injustices he had seen all around him.

It was his finest studio album, cementing his position as one of the most outspoken artists of the 70s. And although he’d suffered at the hands of the ‘shitstem’ many times before, the album notably called not for revenge but for justice. Revenge is personal, justice is political.

Setting out his stall with a version of ‘Get Up, Stand Up’, Tosh makes it clear that equal rights will not come without a fight. He follows this call to arms with ‘Downpressor Man’, a warning to any and all oppressors of him and his brethren. “You can run but you can’t hide” Tosh sings, ominously.

At no point does this record relent from its militant message. “Don’t underestimate my ability,” he sings on ‘I Am That I Am’. And on ‘Stepping Razor’ (the Joe Higgs song Tosh claimed as his own before a legal battle forced him to credit Higgs) he lets it be known in no uncertain terms just how dangerous he is.

He sings on the title track of the album that he doesn’t want peace, but that he needs “equal rights and justice”. It’s here that he asserts his message most powerfully. By dismissing peace so easily, he maintains that what’s needed won’t come without a fight.

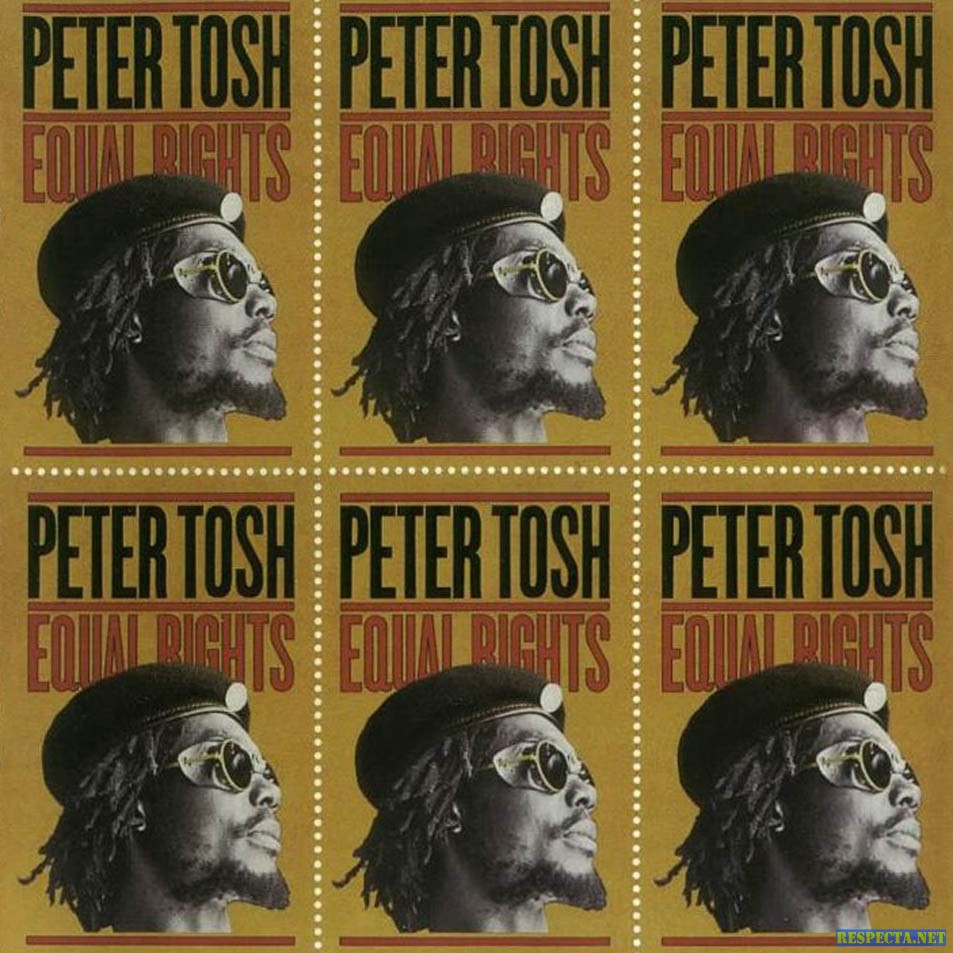

What Tosh hopes to achieve is made clear in the album artwork. Six identical images of Tosh’s face, head turned and wearing a beret and his trademark goggles, are repeated on the cover of the record, calling to mind both propaganda posters during wartime and those of political leaders fighting for office. Look closer and you see that the edges of each image are perforated like a sheet of stamps; the idea of CBS designer Andy Engel.

Those whose images grace postal stamps generally are not singers, they are typically the leaders of countries. It would appear that this is where Tosh saw himself; as a leader of people, leading the fight for equal rights.

But as much as the album is informed by Tosh’s struggle for justice, it is influenced equally by his faith. Tosh had been exposed to the teachings and way of life of the Rastafari as far back as 1963, and by the time he released Equal Rights he was a convert. Both ‘African’ and ‘Jah Guide’ make music of his beliefs. Dealing with identity in the former track, Tosh makes clear that to be black is be African; one of Marcus Garvey’s key teachings. In ‘Jah Guide’ Tosh delivers a rousing justification for the upcoming fight for equal rights: “Jah guide I through this valley.” His path was righteous.

“Every form of victimisation is universal, not only in Jamaica.”

Peter Tosh

Herbie Miller, Tosh’s then-manager and production coordinator has said that the struggle to liberate southern Africa (Zimbabwe, Namibia, South Africa) was a key influence on the album: “The theme of this whole record is to do with that particular struggle, of the Africans in Africa, and the Africans outside Africa.” He said that Tosh had wanted to document this particular struggle with “machine-gun lyrics in a suite tying together songs that all related to those both within and without Africa.”

The final track of Equal Rights, ‘Apartheid’, opens with the sound of gunshots. Eight years before the Artists United Against Apartheid were put together by Steven Van Zandt, Peter Tosh was singing that there were "certain place in Africa, black man get no recognition. You got to fight against apartheid”.

Peter Tosh was murdered in 1987. He didn’t live to see the ending of enforced racial segregation in South Africa, nor Nelson Mandela’s election as the country’s first ever black president in 1994.

Thirty-five years have passed since Tosh called for equal rights and justice. During that time an African American has become President of the United States, Desmond Tutu has won the Nobel Peace Prize for his outspoken criticism of the apartheid regime, and closer to Tosh’s home, an organization called Jamaicans For Justice (JFJ) has been established. Since 1999 JFJ have fought for respect, freedom and the right to a peaceful existence for citizens of Jamaica.

However, just last month in Florida, USA, an unarmed black teenager named Trayvon Martin was shot dead by George Zimmerman, a non-black vigilante, because he “looked suspicious”. Trayvon was walking home to his family carrying a bag of sweets. The case is reminiscent of the 1993 murder of Stephen Lawrence whose death sparked an inquiry that exposed institutional racism in the UK.

Equal Rights is passionate and critical of the world Tosh saw around him, with observations that resonate to this day. Self-produced and recorded with a team of musicians including the rhythm-section powerhouse of Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare who credit their international career to their work on Equal Rights and the subsequent tour to support the album. It is Tosh’s masterpiece.

When recording his Red X tapes, which were intended to form the basis of a never completed autobiography, Peter Tosh said: “I am here to play the music and to communicate with the Father spiritually so I can be inspired to make music to awaken the slumbering mentality of people.”

Equal Rights does just that.