It’s tempting for us old farts, as we dodder ever deeper into our dotage, to turn into the people we swore we’d never be when we were in our teens. You know: the ones who, when confronted with the musical cutting-edge of now, shake their heads in bewilderment and mutter something about how it’s not like it was in our day. This ‘day’ being in the dim and distant pre-history that took place before the internet. Thing is, whether that merely proves we’re out-of-touch and irrelevant, or whether we truly believe that we mean it after performing some kind of empirical comparison between then and now, the fact is that the observation itself, if taken at face value, is unarguable. It truly was a different time.

A quarter of a century ago, there was still a music industry, and record labels both big and small signed artists to long-term deals, expecting to release at least two or three albums before either side gave up on the other. Even modestly successful records sold in significant quantities, and while bootlegging was a problem – as we shall see – it was contained, manageable, and hardly an existential threat. The music news cycle was slow, because the real news cycle was slow: the internet existed but wasn’t widely used outside academia, and the mainstream news media covered music only in exceptional or highly unusual circumstances. You got your information about what was new from a limited number of sources you’d gradually learned to trust: specialist magazines and radio shows (rarely entire stations), the person behind the counter at the record shop you visited in search of new goodies at least a couple of times a week, and word-of-mouth from friends with similar tastes who you actually knew, and met, and had face-to-face conversations with about the music you loved on a pretty frequent basis. So it’s little wonder the music that this ecosystem revolved around sounded and felt very different from that which springs from today’s far more atomised virtual communities.

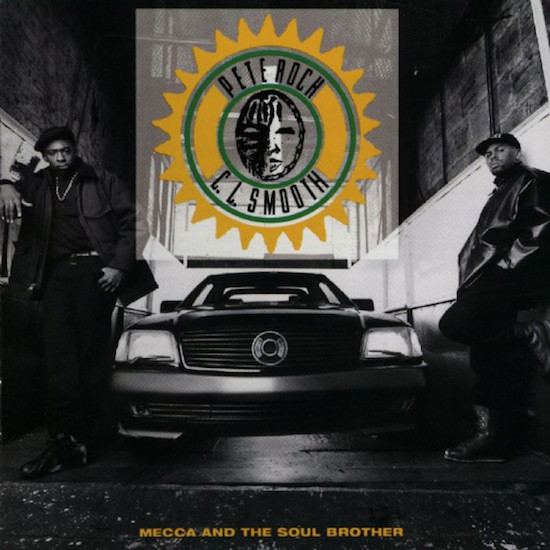

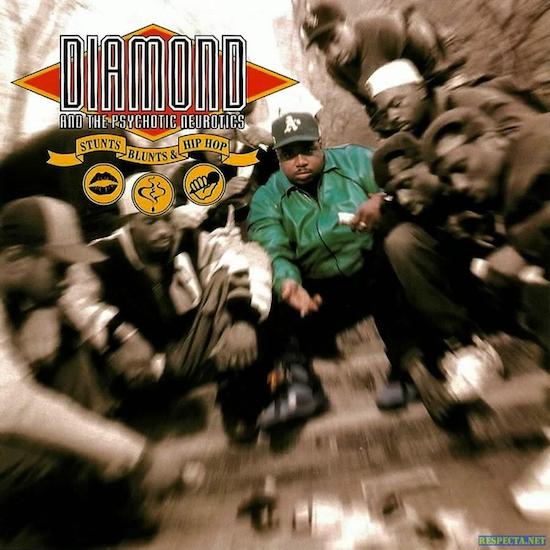

Nowhere are these differences more tangible than in what passes for the edges of the mainstream of hip hop. In 1992, there were – as today – a handful of truly big names who attracted the lion’s share of attention: around them clustered a secondary layer of artists, yet to attain that elevated commercial higher ground but blessed with talent, skill and creative vision sufficient to make listeners believe that their time at the top was surely coming. Among those still on the mezzanine level in 1992, two individuals more or less demand a head-to-head joint evaluation: between them, Diamond D and Pete Rock helped codify a new kind of hip hop artist.

The producer-rapper wasn’t an unknown breed in 1992, but they didn’t do a lot to draw attention to their unusual status. Chuck D was part of the Bomb Squad but disguised his involvement in that part of Public Enemy’s work – he appeared in production credits as Carl Ryder, a corruption of his government name. Both Erick and Parrish carried their share of the production burden on EPMD’s barnstorming records, but one tended to think of them less as a pair of rapper-producers than an uncommonly gifted self-contained group – like De La Soul, who didn’t rely solely on Mase (or Prince Paul) for their beats. There was, of course, Dr Dre – the one towering exception to all other rules, and the only name on any generally acknowledged 92 hip-hop A-list who fans, critics and accountants would likely keep on the 2017 version of the same roll call. He had either produced or claimed credit for a slew of million-selling LPs and had appeared as a vocalist on dozens of records, but his emergence as a bona fide star in his own right was still ongoing in the summer of 1992. The Chronic would eventually, belatedly appear at year’s end: 1993 would be his time. It took a while, but the Kanyes and Pharrells would eventually follow in his slipstream: yet it was Diamond and Pete Rock who set that ship sailing.

The similarities between the two men didn’t end with their decision to work both inside and out of the vocal booth. The New Yorkers sat on the edges of each others’ extended artistic communities, and shared plenty of friends and collaborators. Both were early exponents of the art/science of crate-digging – using record shops as an archaeologist used a field trip, as an opportunity to dig into the past and return with a piece of buried treasure that they could study, learn from, and place in a modern setting, allowing contemporary society to consider it in a new light. As such, both guarded their finds zealously, and while neither man cites competition with the other as a factor in their work, there is some evidence to suggest that the kudos that accrued to the producer who found and used a sample first was an ingredient in the fuel that powered their debut LPs. Both preferred a muscular musicality to just looping breaks: their productions considered key and melody to be as important as beats and impact, setting them apart from many of their peers. Both knew that a cracking solo album would be a far better advertisement of their production capabilities than could be bought in Billboard, and both would enjoy lucrative work off the back of their 1992 releases. And both records, arriving in the early phase of the CD revolution, were released as double albums in single sleeves, but appear to have been sequenced and conceived as single-disc CDs.

Yet there’s plenty to distinguish one record – and one artist – from the other, too. Pete’s album can’t really be considered a solo record – throughout he was partnered with rapper CL Smooth, and while the duo would produce a relatively slim discography together, theirs was a group just as much as Erick and Parrish were EPMD or Premier and Guru were Gang Starr. Diamond’s LP is credited to him and The Psychotic Neurotics, though that became less a working group than a flag of convenience to enable him to work with the circle of friends that would become known as the Diggin’ In The Crates crew – Fat Joe, Big L and Showbiz all guest on the record. Diamond also raps a lot more than Pete: and wrote his own lyrics. Despite the lengthy cast list, his album is more definably a solo record.

Their careers were also subtly out of step with one another: by the summer of 1992, Pete was ahead, despite Diamond having started out earlier. The latter’s first production to surface – ‘I’m The King’, a track for the rapper Raheem that appeared on Jazzy Jay’s Cold Chillin’ In The Studio Live compilation album – had been recorded in 1988, and is a fair reflection of the age it was made. Pete’s first work had been for his cousin, Heavy D, on the swingbeat-heavy Big Tyme LP, and sounds similarly dated. In 1990, Diamond recorded a full album with Master Rob under the name Ultimate Force, but only one track – the Albert King-sampling ‘I’m Not Playing’ – would see the light of day for some time (the entire LP was finally released in 2007). He had also contributed to Lord Finesse and DJ Mike Smooth’s Funky Technician, a record that, while it did get released, suffered from the patchy distribution and promotion that characterised the Wild Pitch label, so remains somewhat neglected. Pete’s 1990 was comparatively quiet – two tracks on Groove B Chill’s largely forgotten attempt to refashion swingbeat for the D.A.I.S.Y. Age, Starting From Zero, was the sum total – but 1991 was his breakthrough. As well as more tracks with Heavy D – including the influential posse cut ‘Don’t Curse’, which saw CL Smooth joining an all-star rap cast (Big Daddy Kane, Grand Puba, Kool G Rap and Q-Tip) – there was a co-production with Large Professor on Main Source’s highly regarded debut, and two A-list remixes: EPMD’s ‘Rampage’ and, right at the close of the year, Public Enemy’s ‘Shut ‘Em Down’.

The latter proved to be arguably the most important release of Pete Rock’s life. PE were the biggest rap band in the world, so the remix for the second single from their Apocalypse 91 album was bound to attract attention simply by its existence. Daringly – and brilliantly – Pete crafted a completely new piece of music to underpin Chuck D’s call to boycott multinationals benefitting from black consumers but putting nothing back into black communities. He didn’t stop at turning the original, harsh, mechanical beat into something funkier: he also did the unthinkable, adding a four-line rap of his own to the middle-eight. The track became one of the most admired releases in PE’s career, and the remix clearly got the band’s seal of approval: it was this version they chose to perform when appearing on British TV during 1992. Not only did this release ensure Pete’s production and remix skills were in high demand for the next 18 months: the record pretty much drew up the sonic template he would cleave to, and gave hip hop a new sound and style that others felt duty bound to either square up against or to attempt to outdo.

The other key release for Pete in 1991 was his and CL’s first record, the All Souled Out EP. At the time, its introduction of the duo wasn’t quite as apparent as the way it shored up the idea of Pete as a double-threat rap star. The decision to release ‘The Creator’ as a single made this inevitable: the only track of the six on which CL didn’t appear, the song was also the most easy-to-grasp piece of music on the record. The uptempo beat is built around a subtly but significantly tweaked loop from Eddie Bo’s Mariachi-tinged soul curio ‘From This Day On’, and just about the only other element is a riff from King Curtis’s ‘Instant Groove’ that appears as a hook. The rest of the track is just Pete letting off on the mic: and if his style sounded somewhat familiar, it might not have needed an assiduous credits reader to work out that Brand Nubian leader Grand Puba had written the lyrics for him. (Somewhere, deep in the back of a bottom drawer somewhere, there surely must be a cassette of ‘The Creator’ with Grand Puba reciting the rhymes for Pete to use as a guide: the flow is too closely patterned to imagine the producer working out his own metre.) Not only is the delivery a giveaway, so is the lyric’s preoccupation with the vocalist’s irresistible attraction to the opposite sex: yet even this tiresome lack of imagination can’t prevent the track from remaining durably infectious.

The release of the Pete and CL debut, then, was rather more keenly anticipated than Diamond’s LP, and Mecca And The Soul Brother came out first – in June, while Stunts, Blunts, & Hip Hop arrived at the end of September. It also benefitted from one of those accidental effects of the "business" part of the music business. It was released by Elektra, part of the Warners stable, and home to a roster of forward-looking hip hop artists mentored by A&R man Dante Ross – the first hip hop A&R appointed by a major – and label head Sylvia Rhone, both of whom keenly understood and obviously very greatly liked the music that they were putting out. Not all of the groups Ross and Rhone signed cracked the big time, but there was a shared aesthetic binding Brand Nubian to Leaders of the New School, KMD to Pete and CL; and Elektra worked hard to ensure each artist they worked with got a fair shake in terms of marketing and promotion. Diamond, by contrast, had signed with Chemistry, a new name for the hip hop imprint established by – and it still sounds bizarre to say this 25 years later – British chart-pop producer, songwriter and DJ Pete Waterman. There was logic to this seemingly odd decision, too: with the resources of a major distributor (Mercury/Polygram) allied to the hit-making prowess of Waterman’s company, and their evident awareness that hip hop was becoming a major strand of the pop marketplace they would be daft not to try hard to make money from, Diamond would have had every reason to believe that he’d not only get the kind of push Elektra were giving their artists, but that there may be less opportunity for a loss of focus when you were – the cult success of Ed O.G. & Da Bulldogs notwithstanding – going to be your label’s number one priority for the year. Truth be told, neither record, in the end, got what could be considered its just dues in the marketplace: both remain connoisseurs’ classics, highly regarded and much loved but without ever having acquired the status of a bona fide hit.

Comparing and contrasting the two releases is inevitable, but it can be the points of divergence between them that prove more revealing. Mecca And The Soul Brother is an album, in the original sense: a collection of snapshots arranged into a sequence; pieces that hang together because they were created around the same time, not necessarily to a concerted or clearly defined design. Stunts, Blunts, & Hip Hop, by contrast – and both for better and for worse – is a concept album, where each song seems to add to a cumulative experience. As such, the bits that don’t work about the former seem less excusable, while the parts of the latter that don’t work so well individually do at least appear to have a purpose and a role to play beyond their own durations. As a result, it is Stunts, Blunts & Hip Hop that probably works better as a cohesive listen, but Mecca that became the more storied release – perhaps in part because of its epochal first single.

Billed as a tribute to Trouble T Roy, a member of Heavy D’s group and a friend of both Pete and CL, who died in 1990 after an accident during a tour stop in Indianapolis, ‘They Reminisce Over You (T.R.O.Y.)’ is actually a meditation on family, friendship and community in which T-Roy is mentioned only briefly, in the final verse. Hip hop still doesn’t tend to deal with introspection terribly well as a lyrical theme, so the track continues to feel like an outlier in subject-matter terms. More remarkably, CL’s writing matches his fluid flow, easing the listener from one vignette to another, rising and falling over a family history told through vivid flashbacks without ever making the experience feel disjointed or jarring – he works in lyrical pans and fades, not jump-cuts or discontinuities. And there is real tenderness here, which adds to the emotional heft. In verse two CL recalls the grandfather who raised him ("took me from a boy to a man so I always had a father/when my biological didn’t bother" – a line so resonant of so personal yet widely shared an experience it became the basis for a track on the debut album by basketball star-turned-rapper Shaquille O’Neal), and discusses his reliance on alcohol: difficult stuff for anyone to put out there, never mind in a pop song. But then there’s this, perhaps one of the gentlest yet strongest and most affecting images to be found in hip hop’s recorded history:

"Never been senile – that’s where you’re wrong

But give the man a taste and he’s gone

Noddin’ off to sleep to a jazz tune

I can hear his head bangin’ on the wall in the next room

I get the pillow and hope I don’t wake him"

If ‘They Reminisce…’ had only been about CL’s lyrics and delivery, it would still make many fans’ all-time top 20s. What elevates it to the high single-digit places is that the words exist inside a fine, empathetic piece of production. The track kicks off – as do many of the songs on the LP – with a disconnected fragment of an unrelated piece of found music – in this case, ‘When She Made Me Promise’ by The Beginning Of The End. (Throughout the record you get the sense that Pete Rock has included these as taunts to his crate-digging peers, as if he’s saying: "See? You thought you were the only one who’s found that, but not only did I get there before you – I’m just going to throw it away in between songs, because I’ve got more and better where that came from.") Then the track proper launches with a loop taken from saxophonist Tom Scott’s version of the Jefferson Airplane song ‘Today’ – a record that ‘They Reminisce…’ made totemic, which features in Diamond D’s discography too (he used different parts of it for a 1993 single by the obscure trio Raazda Ruckus, called ‘Da Chronic Asthmatics’), and comes from an album Pete had already mined for the horns he used to make his ‘Shut ‘Em Down’ remix. As the sax figures dot about across the stereo mix behind CL’s lyrics, and the flute and choir from the same record merge to form the perfect setting for the vocal, drums propel the piece along without ever overwhelming. It is masterful work from both of them.

‘They Reminisce’ became part of one of contemporary hip hop’s perennially tedious online wars-of-words in 2012 when Lupe Fiasco released a song that was a kind of cover version of it. Taking the ‘T.R.O.Y.’ soundbed as its starting point, ‘Around My Way (Freedom Ain’t Free)’ is angry and political, but its power and ability to affect relies – to a considerable extent – on the listener making the emotional and empathetic link back to Pete and CL’s track. Lupe raps about the ills bedevilling American society and the way they are being spread like a virus around the planet: it’s a song written from a place of caring passionately about the issues it raises, but if the listener isn’t on some level thinking of CL’s themes of family and friendship, all you’ll hear in Lupe’s song is its raised-fist protest. As if ignorant of the concept of irony, the Wikipedia entry on a track whose hook bemoans "a bunch of nonsense" that obscures the fact that "freedom ain’t free, ‘specially round my way" uses ten times as many words explaining the two-day misunderstanding over the sample (Lupe got musicians in to re-play it after Pete’s people hadn’t responded to his requests to clear a sample from ‘…Reminisce…’) as it does suggesting what Lupe’s song might have actually been about: there is no discussion whatsoever of its merits – or otherwise – as a piece of art.

Stunts, Blunts & Hip Hop didn’t have a comparable stand-out moment to ‘Reminisce’, but Diamond’s album did inspire possibly the greatest cover version in rap history. ‘Freestyle (Dat Shit) 2006’ appears on De La Soul’s excellent but obscure The Impossible: Mission TV Series Pt. 1 CD, and seems to have escaped the attention of the handful of reviewers at the time, or the online annotators behind otherwise thorough and exhaustive resources such as Rap Genius and Who Sampled. It is a glorious two-and-a-half minutes of affectionate homage, gentle self-parody and heartwarming hip hop trainspottery – a line-by-line reconstruction of Diamond D’s ‘Freestyle (Yo, That’s That Shit)’, based on the same light-hearted skip-along George Benson sample. Diamond’s song shows his nimbleness as an emcee, and – just like Pete and CL did on ‘Reminisce’ – how a skilled emcee and producer can make music and lyrics mean more than they do on their own by ensuring one mirrors and amplifies the inherent qualities of the other, and vice versa. It also gives more of a sense of the jocular but confident character who created Stunts, Blunts & Hip Hop than many of the other tracks on the record: "Always got a buck ‘cos I don’t make wack shit"; "On, on and on just like the Mississippi"; "I write rhymes so much that my hands ache"; "Know a lot of beats but I say no names". There’s even a shout-out to Pete and CL.

Shout-outs and reference points are hardly in short supply on Stunts, Blunts & Hip Hop – surely the only album in rap history to reference both the novels of Agatha Christie (‘Red Light, Green Light’) and the signature Posturepedic product of Cumbrian mattress manufacturer Sealy (‘Step To Me’). And ‘Freestyle’ isn’t the only track that exults in its maker’s likeable sense of humour: the dizzying ‘What You Seek’ opens with him shouting "Holy mackerel!" while the ensuing series of daft metaphors are pitched an inch or two the right side of groan-inspiring. Yet the record probably earns its time in today’s listeners’ headspace due to Diamond’s range of sample source material, and the unique ways he finds to blend the sounds he knew and intuitively understood. There are co-producers credited on some of the album’s tracks, but as Diamond explained in an interview with Robbie Ettelson in 2014, a lot of those folks did little more than lend him a record he later sampled from: certainly this appears to be how Large Professor, Q-Tip and 45 King got their co-producer credits (on ‘Freestyle’, ‘K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple Stupid)’ and ‘Check One, Two’ respectively). It’s tempting to see sample diversity as a key point of differentiation between his album and Mecca And The Soul Brother: yet, despite the overall sonic patina, the idea that Diamond’s palette was broader may miss the mark somewhat.

‘I’m Outta Here’ – three tales of desperate escapes from street beefs, told in a conversational, observational style – certainly doesn’t sound like something Pete Rock might have had a crack at. More or less the entire track comes from blue-eyed soul band Flaming Ember’s 1971 album track ‘Gotta Get Away’. Diamond’s LP intro took drums from a James Taylor outtakes LP while ‘Step To Me’ included a lift from the Delfonics’ ‘Ready Or Not Here I Come (Can’t Hide From Love)’ – accidentally prescient, as one of Diamond’s biggest production paydays (if not a record he seems to have particularly cared for) would come four years later when he produced the title track to the Fugees’ second album, The Score. And when Diamond did use jazz records, he often found things that were exceptions to the expected – witness, for example, the flanger-laden guitar figure he found on a Billy Cobham and George Duke live album that gives ‘Stunts, Blunts, & Hip Hop’ its weird new-wave riff, or the burbling bass line from a 1977 John Handy LP that bounces like a rubber ball throughout ‘"!!" What You Heard’.

All that said, Pete Rock often matched Diamond, sometimes sample for sample. Diamond’s ‘Check One, Two’ relied a snagging guitar hook from Mike Bloomfield, Al Kooper and Stephen Stills’ Super Session album, but there’s part of another track from the same record inside Pete and CL’s ‘The Basement’. Diamond steered clear of the brittle, atmospheric drum sound from Mountain’s live recording of ‘Long Red’, but Pete used it on three different tracks on Mecca – perhaps his way of doffing his cap to early mentor Marley Marl, who had been the first to use those drums in hip hop when he built ‘Eric B Is President’ for Eric and Rakim in 1985. ‘It’s Like That’ took the drums from ‘Mongoose’ by Elephant’s Memory, the one-time live backing band for John Lennon and Yoko Ono. ‘If It Ain’t Rough It Ain’t Right’ somehow incorporates the bass line of Talking Heads’ ‘Once In A Lifetime’. As if his name held wider significance, rock was far from foreign territory for Pete.

But it’s clear that Pete’s finest work was done when working with samples found in the blurred margins between soul and jazz – and when he was on fire, so was CL. ‘Straighten It Out’ is, in all but its emotional resonance, as exquisite a single as ‘Reminisce’: Pete found the forgotten belter ‘Our Generation’ by Ernie Hines and recognised its potential for a foundational loop, adding drums from Simtec & Wylie’s head-snapping ‘Bootleggin” as not just aural but conceptual underpinning for a lyric in which CL muses, in part, on how street-corner counterfeit tape-sellers were doing New York rappers out of their royalties. Verse two finds him broadening his remit to discuss the problems producers were finding as the sample-clearance sub-industry emerged, while the final stanza finds him addressing racism in the music business. In each verse, he ends with a call for unity among artists as the only way of making positive progress. In 2010 the implied circle was finally closed, when CL guested with The Roots and John Legend to rap a verse on a cover of Hines’ original – enshrining both ‘Our Generation’ and ‘Straighten It Out’ in the canon of black-power-inspired protest anthems.

A typical burst of inspiration occurs mid-album with the utterly berserk ‘Wig Out’, where a lovely vibraphone loop (from the 1967 bossa nova-styled track ‘Jungle Child’ by Johnny Lytle) is laid on top of arguably the heaviest drum break to be found on either album: that it comes not from some metal band’s live LP nor from a bootleg recording of The JB’s in rehearsal, but a swaggering bit of swinging 60s London courtesy of Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames (the track is a cover of Stevie Wonder’s ‘Music Talk’, which Fame probably came across first in a version by Liverpudlian singer Beryl Marsden; the drum stool in Fame’s band, the Blue Flames, was occuped at that time by Mitch Mitchell, who left in October of 1966 to join the Jimi Hendrix Experience), merely underlines the conceptual thoroughness with which the track was put together. CL gets in on the act too, his melange of non-sequitur imagery all adding up to a kind of sense-out-of-nonsense, reaching a magnificent culmination in the final stanza where he lays bare the process of the song’s construction and the duo’s interlocking working method even as he’s performing it ("Pete knowledge me, flip it over and it’s sweet/Entwined when I mentally design verse three"). At the end of most lines, Pete arrives with an ad-libbed "Uh", "Yeah" or "Whoo!", confirming the unprecedented integration of music and lyrics, producer and rapper – perhaps as only one who had done a bit of both could ever properly manage.

Both records have flaws, and both of them share one depressingly common failing: an attitude towards women that makes parts of each difficult to listen to and impossible to like. To be fair to Diamond, ‘Sally Got A One-Track Mind’ appears to have been less a case of unreconstructed sexism than a misguided attempt at positivity: he told Robbie Ettelson that the intention of the song was to act as a cautionary tale to his kid sister, an exhortation to ignore vacuity and mendacity and to stay true to herself. That it lacks anything other than negative stereotypes for her to learn from might not have seemed important to him at the time, but leaves an otherwise well-intentioned track – in which the melancholy melody certainly lends some tragic gravitas to the lyric’s low-key dramas – being distinctly uncomfortable listening. Misgivings are not exactly eased by the first verse of the title track, which – echoing the sex-drugs-rock & roll concept – looks at women solely as sex objects. The women who appear in the narrative in ‘Red Light, Green Light’ may be slightly more fully drawn – if not quite characters, they’re at least a little bit more than caricatures – but again, the reductive, limited view of male-female relations is as inescapable as it is indefensible. On Mecca And The Soul Brother, where the thoughtful CL is kept to the forefront, the overall level of banality is lower – but the closing ‘Skinz’, where Pete’s ghostwriter Grand Puba gets a verse of his own, is a pretty dismal way to end what had been, to that point, an almost flawless record.

What happened to the principals in the immediate aftermath of these records’ releases is instructive. Both Pete Rock and Diamond D helped shape the sound of east-coast hip hop for the next 18 months, as the records they had made and the interlocking circles of friendship and influence they belonged to continued to have resonance for anyone interested by or active in New York-style rap. It would be that other producer-rapper, the one on the opposite side of America, who would go on to dominate, though: suggesting not just that the musical styles Pete and Diamond pioneered were too complicated or perhaps too sample-heavy for the post-golden-age era, but that perhaps rappers blessed with the mellifluous dexterity and syntax-busting complexity of CL Smooth were unsuited to the coming period of dominance by lowest-common-denominator bullshit. For all that these records lacked class and wit when they discussed women, both read like Germaine Greer when set next to some of what would soon follow out of Los Angeles and beyond. Rap music was about to become a commodity, and people who approached it with integrity and a determination to expand its potential would find the years it spent at the commercial zenith to be profoundly challenging.

Pete and CL followed up Mecca And The Soul Brother with The Main Ingredient in 1994: it’s a better record even than their debut, but struggled to find an audience in a changed hip hop landscape, where thug fictions and misogyny were all the new mass market seemed primed to accept. It took Diamond five years to create another solo LP, and even calling it Hatred, Passions & Infidelity failed to help it chime loudly enough with the changing times. Pete and CL broke up and, despite a superb, notionally "solo" 1998 LP called Soul Survivor where Pete recorded with an all-star cast of rappers of the last years of the 20th century, the production style pioneered by the crate-diggers went from the cutting edge of rap to the preserve of a new breed of retro hipster, to be appreciated more for what it said about the consumer than for its considerable intrinsic merits.

So, no: these are not records that can very readily or usefully be compared to anything going on today. Yet both either began or amplified different vibrations that continue to sound through the ether. Revisiting them does not feel like unearthing a time capsule, nor does it seem to suggest that clues to the future might have been left buried in the past. Both remain vibrant, occasionally exasperating, frequently exciting, and roundly, superbly entertaining examples of music made by people who knew how good they were, knew why they were as good as they were, and weren’t ready to stop trying to move themselves and their music forward.