I remember buying The Tenement Year on cassette in Canterbury city centre in 1988, along with Loaded by the Velvet Underground and a bottle of red label Thunderbird. I was 18 and had visited the city to attend an interview for a course at the university. I had been reading a music paper on the train on my way there. As was my habit then, I would always take note whenever an artist I liked mentioned bands who inspired them. It was in an interview with Frank Black of the Pixies, in either Sounds or Melody Maker, where I saw them mentioned that morning.

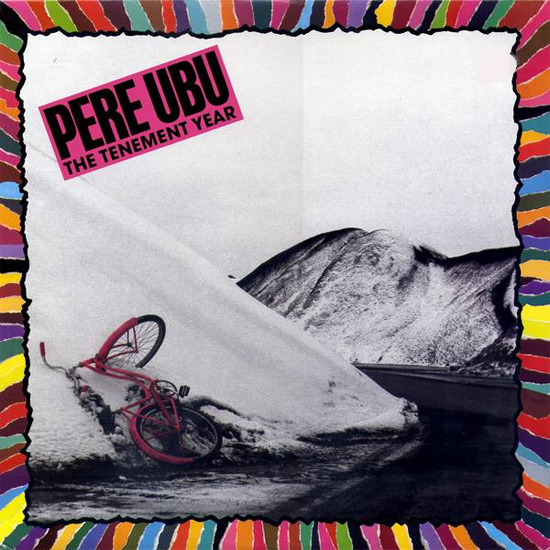

This was how I came to Pere Ubu, and more specifically, The Tenement Year – the first album that I bought by them. The bizarre yet striking cover kind of put me in mind of that Smiths lyric, "punctured bicycle on a hillside desolate", although I came to realise later that the garishness of the crayon-scrawled border against the grainy black and white backdrop and the queasy shade of blancmange pink in the logo was very much in keeping with the band’s aesthetic. A better explanation of the album’s cover is hinted at on the Ubu Projex website, where it is stated that the album "was designed to be a clattery heap".

Certainly, when I retired to my guesthouse bedroom, cracked open the Thunderbird and put the album on my Walkman, I hadn’t heard anything remotely like it. I think it was that voice and that synthesiser sound that did it, and the bizarre lyrics also, printed inside – not normally something David Thomas is keen on. Although it is considered the beginning of the pop-era Ubu, which a lot of fans of the earlier material don’t always appreciate, it is an album which retains its appeal to this day, without losing any of its sense of otherness.

Pere Ubu’s historical period consists of a number of classic early singles on their own Hearthen label, followed by three albums: The Modern Dance, Dub Housing and New Picnic Time. The fractious recording sessions for the third album led to the band briefly splitting in 1979 and reforming, months later, with Red Krayola main man Mayo Thompson replacing Tom Herman on guitar. After that formation of the band had recorded The Art of Walking, Scott Krauss was replaced by Anton Fier (who plays on the excellent first Feelies’ album and who later went on to form the Golden Palominos) on drums for the recording of Song of the Bailing Man.

Although the first two albums were widely regarded as masterpieces, each successive recording tended towards being increasingly abstract and markedly less visceral, to the point where it eventually seemed as though the band had painted themselves into a corner. Scott Krauss and bass player Tony Maimone went on to form Home And Garden. Frontman David Thomas continued with his own material, abetted by a varying roster of underground-music luminaries, including Richard Thompson and members of Henry Cow. By the time Blame The Messenger was recorded in 1987, the band’s line-up already featured a number of Ubu members and had also begun performing some old songs as part of their live set.

A full reactivation of Pere Ubu began in 1988, with the recording of The Tenement Year. The band consisted of core members David Thomas, on vocals, trombone and melodeon; Allen Ravenstine on EML synthesisers and sax; Tony Maimone on bass and Scott Krauss on drums. They were joined by Ohio scenester Jim Jones, who had previously been in the Mirrors and the Styrenes, on guitar, and the always astounding Henry Cow drummer Chris ‘Cutlery’ Cutler on second drum kit.

In many ways, I just don’t get certain fans’ refusal to accept the validity of the pop albums. Pere Ubu are a band that have released a diverse range of material, all of which adds a great deal to their appeal. The pop element has always been there anyway. Surely no one would try to argue that David Thomas became such a staunch Brian Wilson and Van Dyke Parks fan (as evidenced in Thomas’ cover of ‘Surfer Girl’ and the Ubu song ‘Wine Dark Sparks’) only later in life? A quick glance at the words of ‘On the Surface’ from Dub Housing is a perfect example the kind of pop lyric (albeit in an unusual context), that has always interested Thomas: "I heard the radio sun / made the day like a beach / Lost & in love / I was sand in the surf / I heard talk / It was a day like a beach."

I have even heard it said, as on NYC-based music blogger Mark Prindle’s archive, that The Tenement Year sounded ‘just like all the other alternative rock albums that came out that year’ but with "weird keyboard noises over the top". In retrospect, I think it’s safe to say that no other album released in that year, or any other, sounded anything like The Tenement Year. Critical response, on the other hand, was generally very positive, with Edwin Pouncey at the NME calling it "this year’s manna from heaven", and Adam Sweeting in The Guardian writing: "As if a mountainside had learned to play Mendelssohn… Even when they make no literal sense, Ubu have the alluring and deceptive plasticity of a foreign language."

So The Tenement Year is the beginning of the pop Ubu era and undoubtedly the best of that era. There are some great tunes and also some amazing sounds – Ravenstine’s inspired synth work, Jones’ angular guitars, Chris Cutler’s clattering yet spacious percussion and David Thomas’s soaring, tremulous warble are all essential parts of the mix. It is the most experimental of their pop albums and yet contains a very high number of classic tracks.

Opener ‘Something’s Gotta Give’ kicks it all off with oscillating sine waves and a reggae-like skank against which David Thomas’s high wavering vocal proclaims sinister, surrealistic non sequiturs: "Welcome to our town / people swept along! / People swept along & how? / With goats, cats, dogs and hats / oozing down the chimney fast." ‘George Had A Hat’ – a fast-paced avant-garage number with trombone that sounds like a wounded elephant and Silver Apples-like sci-fi overloaded keyboard – is the closest on the album to the Ubu of old, along with ‘Universal Vibration.’

‘Talk To Me’ begins with a bubblegum bass line which briefly threatens to turn into something from the musical Grease, before transforming into a pop hit from a parallel world, where guitar strings are made of elastic, robot cicadas’ tymbals thrum and the former Crocus Behemoth’s vocal swoops and pirouettes like an outsized alien songbird.

‘Busman’s Honeymoon’ comes on like a sea shanty recorded by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and Can. ‘Say Goodbye’ could have been a potential new-wave pop success, with a strong hook to the chorus and a great line in "How can I leave you when you won’t go away / to be caught in the middle / neither night neither day."

‘Miss You’ is perhaps the album’s best track, almost folky with the melodeon, but with an intense vocal and ludicrous keyboard noises. It has a certain amount of swank to it also, as though it’s walking its warped walk with simultaneous awkward grace and arrogance. It’s the incredible beats that propel the song that cause that: the way they surge towards the end, to combine with its final sustained guitar note. A beautiful, romantic sounding, yet warped as if underwater song with a crazy but incredibly assured vocal. ‘Dream the Moon’ is almost as good, a sci-fi racket, reminiscent of an otherworldly jungle, strange alien animals bellowing in the distance, crazy bass line, impossible to dance to without danger of succumbing to seizure.

‘The Hollow Earth’ is yet another highlight, stratospherically upbeat with persistent bubbling sounds from Ravenstine’s synth and Jim Jones’s trebly guitar staking out its own territory in the higher end of the mix, like the theme tune to a really bizarre TV sci-fi show. It also has a really great lyric: "I dropped down a hole / I found the hollow earth / I woke up in a land of extremes / To find the worst that could be / That everything would be / Just what it seems."

The album ends with ‘We Have The Technology’, the track they played on the Roland Rat show, as David Thomas recalled in a recent Quietus interview. I remember sneaking out of sixth form early that day, still not really believing what my friend had told me about them appearing on the show. To my astonishment Roland Rat introduced them as "my dear friends, Pere Ubu".

I remember it looked as though they were very obviously miming, some of the band were rolling up bits of paper and chucking them into nearby waste paper baskets while others were fiddling with old-fashioned radio dials. To begin with, I thought the tune itself could be considered fairly normal if it weren’t for the vocal delivery and Ravenstine’s woozy keyboard noises, but then I got sucked into its askew ambience – and wasn’t sure what normality was anymore.

The song’s words read like a paean to modern technology, although as with a lot of Thomas’s lines, there’s a hint of something darker underneath. "We have the technology / But thinkers and the poets of the past / Oh, no / They had to leap into the dark so blindly / Whereas we’ll stand free & upright like men / The day’s golden light! / Linked with our machines our eyes are beaming / It won’t matter at all / How weird things are seeming."

After The Tenement Year, Pere Ubu would go on to release three more increasingly (by their own standards) straight pop records: Cloudland, Worlds in Collision and Story of My Life. While Cloudland is an excellent album, the law of diminishing returns began to take effect for the two that followed in its wake. There are, however, still some great songs on both of those albums, and as a good indication of the quality of the material from across the Ubu pop period, recordings of some great (and fairly different) live versions exist. London Texas features both Chris Cutler and Scott Krauss on drums, with additional keyboards from Eric Drew Feldman, who had worked with Captain Beefheart and whom David Thomas allegedly poached from Snakefinger’s Vestal Virgins.

Apocalypse Now was recorded while the band were on tour with the Pixies in 1991, and was performed with ‘acoustic guitars and an out-of-tune honky-tonk piano’. By 1995, the band had returned to a harder, more avant-garage inflected sound with the excellent Raygun Suitcase. Whilst I personally have a great affection for almost all of the band’s albums, The Tenement Year stands as a very special document of a band in between phases, moving away from the abstract and musique concrete influences of earlier material and towards an intrinsically American pop identity that was still very much their own. As David Thomas said in an interview from Rocking In The UK circa 1989, whilst illustratively turning a plastic cup in his hands: "You have to see if from all the different angles, one album we do is going to be like this [lifting the cup so you can only see the bottom]… if you only know a cup this way [holding it so the side is visible], you don’t know the cup."