My induction into the Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark-obsessive fan club came later in life than I’d like to admit. Reading Richard Houghton’s oral history of the band, Pretending To See The Future, I realise that the stories of people on the ground – that begin with the release of the single ‘Electricity’ a month before I was even born – are the types of authenticity that my own discovery can’t touch. Sure, I’d heard a hit single here and there on the radio, but it was such a passive appreciation I might as well have been listening to Muzak.

I first properly "heard" OMD in 2011. The simple story is that I was attempting to cope with sun-bleached life in San Diego, California, where I’d just moved from Detroit to begin my PhD. While many would jump at the chance to live in a "perfect climate" that was predictably sunny, smooth wavy vibes all the time and whatnot, my reaction was less positive. This is where the narrative takes a complicated turn. The sun felt relentless. The lack of extreme seasons was uncanny in how it seemed to neutralise the passage of time. And despite having a full-ride scholarship, I was utterly destitute – surrounded by discomforting "YOLO" privilege and the horror vacui of hyper capitalism everywhere.

The weekend before classes began, I was observing the "International Conclave Of Light" event, hosted by a metaphysical religious group called the Unarians. I felt the first tickle of something being "not quite right" while watching live doves being released from a tiny UFO perched on top of the Unarian’s vintage Cadillac airbrushed with the slogan "Welcome, Space Brothers". It was a vague sensation that had nothing to do with the interdimensional spectacle I was witnessing.

I pushed it out of mind, but a week later it was impossible to focus my eyes. My joints began to ache and stiffen, my skin burned like it was on fire. A gentle touch made me recoil like I’d received an electric shock. Hot red buzzing imprints would remain afterward. My words began to slur, and I had difficulty stringing sentences together, which sent my usually even-keeled personality into rages of frustration. I was suddenly having difficulty understanding simple terms that had defined my academic career like "the media" and "society." I was typing like a third grader and my handwriting wasn’t my own. I had splitting migraines that turned the California sun into a nuclear after-flash. I was pushing through a world made of painful water, and desperately trying to keep ahold of it as it was streaming through my hands. There is a notebook somewhere, full of repetitive black scribbles that I made while sitting in class, trying to root myself in place. I’ve tried to find that book a few times in my basement, but it seems to be lost – or perhaps it never existed.

Everything became thoroughly scrambled. I realise it might seem unfair to pin my plight on the state of California – really, this could have happened anywhere – but I think in part, it was alienation with my new landscape that helped send my already janky immune system into shock. With symptoms spinning out of control, my partner and I walked into an appointment at the campus doctor, who sent us to the main hospital, believing I might have had a stroke. I was in a state of silent terror as I was ushered into the emergency room, where blood was drawn, limb response tested, and penlights shone into my eyes. The ER doctor refused to go any further until I underwent a spinal tap, believing I might have encephalitis.

What followed was the most excruciating hour of my life, as four to five hospital staff fussed around, jabbing a needle in my spine over and over again, failing to get a sample each time. I threw up from the pain and the world went black for a bit before I agreed to be admitted overnight. I slept, unaware, through MRIs and CT scans, and a second successful spinal tap was done under an X-Ray machine sometime in the middle of the night. That, I was aware of. I surfaced the next day, seeing quadruple as a technician scrubbed electrodes into place on my scalp for an EEG.

The symptoms didn’t fully mesh with any one thing. Lyme disease? Lupus? Epstein-Barr? A few days later, throwing up their hands, the doctors sent me home. My back had fused like a solid plank of wood and a baseball-sized spasm formed right above where the spinal tap had been taken. I slept for 14 hours a day for about a month straight, wading through some grey ethereal limbo as I followed orders to give in to the fatigue and rest. I guess I went to classes here and there, with my partner acting as medically appointed notetaker as I sat silently, not understanding much. One day, I woke up with half of my face gone slack and buzzing like a sea of ants – I’d developed Bell’s Palsy on top of everything else. The fatigue remained profound, no matter how much I slept.

ELECTRICITY

Those first few months, I watched a lot of skateboarding videos, dreaming of bodily flight, shucking and carving around on a deck like a skater boy. My thoughts and words were fragmented into telegraph-like pulses. It was during this time that OMD and these synapses clicked together. Cooking meals might as well have been running a marathon, so my partner and I would often frequent the anarchist taco shop across the street from our apartment. It was there that I had my first "nearly drop-your-soda, the world has fallen away except for this song" kind of moment as their jukebox began to play ‘Electricity’. I felt the first jolt of serotonin in forever – I swear my vision went white with the wash of euphoria.

I soon realised multiple versions of the song existed. I would drift off trying to analyse the differences between the album version and the Factory Records single version, produced by Martin Hannett (overproduced, according the band). To my ears, the DinDisc version produced by Mike Howlett during the Organisation sessions was the best, with its catch-and-crick hesitation, slightly slowed, struggling to push sounds through the raw vacuum of tape space. The tension in the track seemed to mimic my exasperation, hitting an invisible barrier as I tried to push words and sentences out of my mouth. Sure, the song was about literal energy, but to me, lyrics about "wasted energy" and "all we need to live today" were metaphors for my own frustration and day-by-day reactive living.

In their early years, while strapped for cash, Paul Humphreys leveraged knowledge gleaned by poking and prodding at the guts of old radios into the ad hoc creation of some of the band’s first rudimentary electronic equipment. Percussion boxes built from the bottom up create those ‘pew-pew’ drum snaps on the first recordings of Electricity. Toying with possible sonic worlds from the inside of a garage.

The video for ‘Electricity’ sums up the truly delightful dorkiness that I love about the band: a custom-built set filled with flashing vertical fluorescent bulbs, cardigans on synth players, staccato dancing and earnest eye contact next to stock footage of popping toasters, hair dryers, electrical towers and computer control systems – and one rotating rotisserie chicken, because why not? OMD wasn’t alone in turning their attention to technology. On the August 1979 Sounds chart, ‘Electricity’ comes in second to ‘Xerox’ by Adam & the Ants, with further charting by ‘Electric Heat’ by the Visitors, and ‘Get Off The Phone’ by The Heartbreakers.

Diversifying from single-track obsession, I eased into ‘Messages’ with its arpeggiated radar skip weaving around persistent organ drones. That bass groove around the 3:12 mark – just as Andy McCluskey’s vocals rise to new caterwauling heights – served as a sonic life force to get me up off the couch. While listening to OMD’s self-titled LP on a loop, it felt like there was hope that my brain could begin to mend itself back together. Looking back, several years on, I can see that exact moment of hearing ‘Electricity’ in a taco shop as being the catalyst for the beginning of my recovery, ridiculous as that may seem.

Running in the background, I was at a different doctor several times a week. I had become a medical mystery. There were infectious disease doctors, pain management specialists, and rheumatologists. Perhaps it was my desperation for concrete answers that made me agree to strip naked in front of a group of curious dermatologists in training. There was also physical therapy three times a week to coax my muscles out of spasm – the TENS machine sending electrical impulses through my muscles and a colourful network of Peter Saville-like PT tape applied to my body each visit.

VOIDS

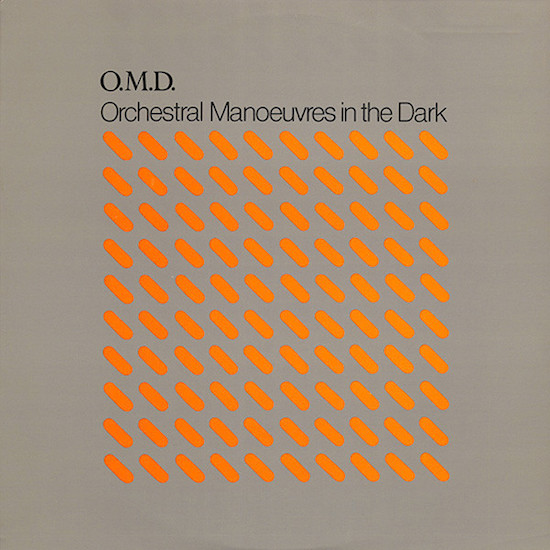

Close to a year in, I was undergoing a reaction test where you’re expected to hit a button if you see a red square flash on a computer screen. I fell asleep upright in my chair, lulled by the promise of a flickering light appearing at random in a black void. Voids seemed to rule that time, for a while. Already a huge fan of Peter Saville’s design follies, I respected his tactile flip-flops between visual planes for OMD’s first releases. There were the shades of black on black for the original ‘Electricity’ single, and the die-cut pill forms of orange-thru-blue of the self-titled album. Blank spaces were produced by sliding the record out, echoing micro-movements in my own life between states of potential clarity and despondent stasis. My partner was looped into this whole mess, ferrying me around to doctors and stressing out while watching me shuffle around like a shell of a human. He made a series of digital collages that paired photographs of everyday life dominated by a floating, gradient void. There’s one of me, completely blown out on the couch a few days after being in hospital, with a green and pink tesseract obscuring my head.

The fall of 2011 until the spring of 2013 is a stretch of time that is its own kind of void, filled with random memory gaps, like a computer in need of defragmenting. There were some good moments in the mix, but in general those two years of life in California are a miasma. Sorting through notebooks from that time, I found a set of snapshots I’d apparently purchased at a swap meet in Los Angeles, tucked in between pages. A man in Detroit Lions pyjamas juggling bananas with a box over his head. Metaphysically, these photos seem to sum up the whole debacle.

DAZZLE SHIPS

In the summer of 2013, I found a battered copy of Dazzle Ships in a record shop, which unequivocally became my favourite OMD release. I encountered Dazzle Ships without the knowledge that it had been a failure when it was first released. How could a record filled with these pure pop jams and sound collages – the drawling ghostly guts of speech synthesiser chips in children’s toys, hauntological trumpet calls, transmissions and tape loops signal hopping their way straight into some secret numbers station – not be successful? Listening to it now, it is hard to imagine people being so affronted by this nerdy gleaming record of synth-pop and history, all tangled up together.

If my ability to speak and think in the fall of 2011 had been demoted into the stuttering pulse of Morse code dots, the longer sweeps of dashes had begun to fill back in. Everything was becoming more cohesive as my ability to think, move, and communicate improved. After a year of visiting doctors, a diagnosis was finally determined to be a chronic central nervous system disorder. It might never go away, but at least the door opened to a treatment plan. Physical therapy released me into the wilds with a Yoga For The Elderly DVD in hand and soon, I could pick up a pencil off the floor without wincing.

That summer, I took a trip to Paolo Soleri’s Arcosanti complex in Arizona – a special kind of void, all its own. I listened to ‘Genetic Engineering’ while walking around a quasi-techno-utopian complex in the Sonoran Desert and the song seemed to fill every grain of sand with triumphant possibility. There was giddiness in the suite of heraldic submarine blasts on ‘Dazzle Ships (Parts II, III and VII)’, the collage of speaking clocks on ‘Time Zones’, and the sound of a short wave radio scanning for a frequency at the beginning of ‘Radio Waves’.

While driven to insomnia one night by the clicks of unfamiliar nocturnal desert insects, I negotiated a weak internet connection into letting me watch the video for ‘Telegraph’. The action unfolds in a nowhere place: a black background and a fog-filled foreground. Television sets blink out the title of the song, clips of the band seemingly shot straight through a CRT-tube filter, women waving wands of light, and an oversized telegraph key round it all out. The Manor version of ‘Telegraph’ is more aggressive in its delivery, with McCluskey outraged as he sings: "God in his mercy looked down on me / said you’re the sinner / that you ought to be," and snidely, "God’s got a telegraph on his side / it makes him powerful / gives him pride." In the end, it "doesn’t mean a damn thing" and the gross growling croak of a synth that isn’t audible on the album version tends to agree.

EMBODIED

How my OMD-appreciation was so delayed is a mystery, especially given my profound love of Kraftwerk. The two bands are quite different, it turns out. I was attracted to OMD’s lack of pretence – that underlying sense of melancholy with soft edges. The machines and industry they sang about were humanised and filled with emotion. Somehow, they managed to turn broad technologies into singular characters. The confidence of the LPC speech synthesiser chip of the Speak n’ Spell used on ‘Genetic Engineering’ is slightly unsettling, especially when paired in a corrective exchange with humans. They encoded the voices of machines in their music, but it wasn’t always from a state of celebration. They seemed to be saying there is beauty in the bleakness of industry, intrigue in the imprints of wartime technology. But we should also be cognisant of automation and scientific processes to which we cede too much control.

Now back in Detroit for close to seven years, I’ve been working as a curator of technology at a large museum. In my day to day, I am often amused to be the keeper of the physical origin points of the types of technology that OMD would come to sing about or owe credit to. In a door just behind my office, lined up on archive shelves are Thomas Edison’s experiments with telegraphy and lighting, John Hays Hammond Jr.’s radio control systems for torpedoes, a radio that was once installed on the SS Leviathan (which was painted with dazzle camouflage during WWI), signal flags, fledgling computers, a radio designed by science fiction publisher Hugo Gernsback, a group of the first transistors from Bell Labs – and the prototype for the Moog synthesiser.

I believe that OMD’s output has created a mirror world for the history of embodied, social technology. Case in point: who names their tape recorder Winston and puts it on stage as a performer? The means the band used to produce their iconic sound wouldn’t have been possible without the technology they were singing about. No synthesisers without electricity. OMD gave full credit, and they weren’t embarrassed to get down into the grains.

Likewise, this is the first time I’ve allowed myself to sink into the quicksand of the bizarre conditions surrounding my 2011-13, to re-examine them in such close detail. I assure you, no sense of catharsis occurred in the process – except perhaps overcoming my discomfort of talking openly about my experiences with chronic illness. I certainly don’t expect a slap on the back or pity. I suppose it’s all just an acknowledgement of how I came to understand OMD, and how, through some fortuitous encounter with their music, I started to scrabble my way back from the strange edge of nowhere and reassemble a sense of myself again.