It’s a quarter of a century since rock last held unquestioned sway over mainstream popular music. Not coincidentally, it’s a quarter of a century since straight white guys from Britain and America did the same. In a further lack of coincidence, it’s a quarter of a century since the peak of seemingly disparate movements in those places – Britpop and grunge, respectively – which had a great deal more in common than was apparent at the time.

Both were fundamentally retrogressive. Each was, depending on how you prefer to see it, a last hurrah or a dead cat bounce for the musical form it represented – as a force of invention, if not a commercial one. In the case of Britpop, this manifested in the fetishisation of the mid-1960s less as a glorious and effervescent creative swirl always grasping at the new (which they were, for a while), and more as a Swinging London theme park in which make-believe came true through faith and fanboy mimicry. While grunge, for all its out-with-the-old posturing, harked back to the kind of trad rock whose year zero is 1968, and whose definitive constituents are the singer as howling priest of hypermasculinity and the guitarist as an axe-wielding demigod; or maybe, by that point, a hemidemisemigod, this being the twilight of such deities.

What lives on of these movements? What from that time has lasted and, it appears, will last in the collective memory? In both cases, for the most part, the things that didn’t quite fit in. With Britpop, the queerer and artier acts that snuck through the door it kicked open, the likes of Suede and Pulp (granted, nobody’s forgotten Oasis, but that meteorite of a first album aside, they were instant dinosaurs – functionally extinct, but still stomping around, too big to avoid.) With grunge, curiously, it’s the band that did the door-kicking in the first place who didn’t quite fit in; the standard-bearers who never belonged to the actual army. Nirvana stand alongside other, more cultish figures, such as thunderous, doomy backwoods neo-pysch group Screaming Trees (more of them anon), soul-by-other-means rockers Afghan Whigs, and sinister liquid-metal act Alice In Chains, as a grunge band who weren’t; who had far more intriguing and expansive and exotic ideas.

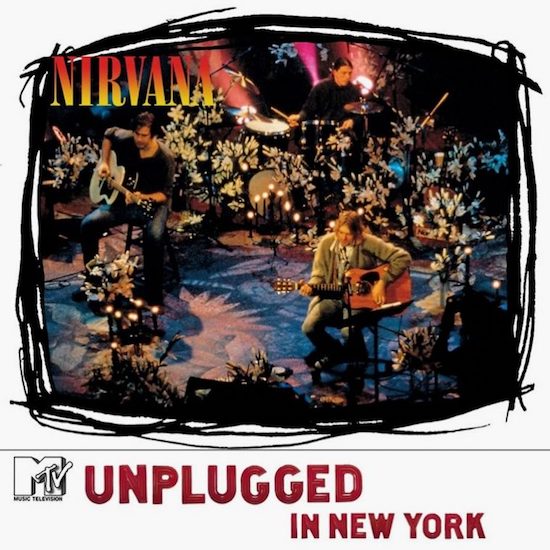

And the artefact, the document, that shows this most clearly is also a quarter of a century old. It was the first album released by Nirvana after the death of Kurt Cobain, and it was a huge commercial and critical success (although one suspects almost anything bearing the band’s name would have been at that juncture.) It’s also – and while this would certainly have been a provocative claim at the time, the passage of those 25 years seems to bear it out – the best thing they ever did. It’s their masterpiece. You might not be able to invoke MTV Unplugged In New York to explain why Nirvana were popular, but today it is exhibit A in the case for their greatness.

At the time it was recorded – November 1993, a year before its eventual release – Nirvana had issued five singles that could be described as hits (and only two earlier ones that couldn’t.) Just one of these, ‘Come As You Are’, made the setlist for the MTV session. This was a collection of deep cuts and covers, the latter (six) outnumbering the original songs from any one Nirvana album (Nevermind supplied most, with four). Not only would MTV Unplugged In New York prove entirely different to any other Nirvana album, it was intended to be entirely different to any other Unplugged recording – and tellingly, no other entry in the series has attained its classic status, or anything close to it.

The implicit idea behind the Unplugged setup was that, by converting their songs to an acoustic format, acts would not only uncover those songs’ true qualities – Behold! Here they stand, unadorned and naked! Judge them now, without gaudy fripperies to conceal or enhance! – but somehow strip themselves down to their core, reveal their essence. Which would, crucially, render their music more authentic. Because we all know that acoustic = authentic and electronic = artificial, right? We’ve known it at least since Dylan went electric. It’s pop music’s own #nofilter hashtag, its equivalent of the pompous bores who blather on about how they think women are just more beautiful, more natural, without make-up, as if it’s any of their damn business. Which ties into why, so often, an Unplugged session would come over as little more than somebody making a virtue of busking their own hits.

Nirvana were having none of it.

Perhaps Cobain understood that the essence of any given piece of music might just as easily lie in its supposed artificiality, that this artificiality is no more or less authentic than a strummed-and-hummed version. Whether he would have thought about it or put it that way, who knows; he was an artist, a great one, and he may have been operating on instinct rather than theory. But instinct should not be confused with accident. And none of the things that make MTV Unplugged In New York so marvellous were accidental.

For a start, there is the performance he turned in; a performance of such wrenching emotional tension and commitment and – let’s not pretend otherwise – craft (he was a showbiz pro by this point; he knew exactly what he was doing) that it would have graced any format, any arrangement. This is not to suggest the other members of the band, and the wider ensemble on the night, were dispensible. Just that Cobain was, as ever, the glowing centre of the thing, and it was always going to stand or fall on what he did.

Also: he cheated. This performance wasn’t “unplugged” at all, in the customary sense that the only amplification was via microphone. Cobain ran his acoustic guitar through pedals and an amp, this rig being disguised as a monitor. And because pop music is not a sporting contest, nor a feat of spectacle like chainsaw juggling, but an art form, he was right to cheat. Cheating is, frequently, how you make the good things happen. Everybody should cheat in pop music whenever possible, as long as it makes the results more enthralling. Which this did.

Then there’s the way he turned the foremost alternative rock band of the day into an Americana group. Grunge was widely considered a direct offshoot of punk rock, which seems fanciful in hindsight, but should be remembered in the context of an American understanding of the term very different to the British one. Punk had never “broken” as a short-lived national phenomenon in America the way it did in the UK, instead becoming a catch-all term for a continuously active, evolving and diverse underground scene. The perception of grunge as a variation on punk owed a great deal to Nirvana having been signed to DGC records on the recommendation of Sonic Youth; but then, to reiterate, whatever a grunge band was, Nirvana weren’t it. They were closer to punk than they were to most of their contemporaries, in their concision, their sharpness, their explosive energy. And when it came to doing an acoustic show, they still managed to showcase a form of punk – cowpunk, the countrified punk sound represented by Meat Puppets, three of whose songs they played in the company of that band’s Kirkwood brothers. They also strongly echoed, deliberately or not, the folk punk of Violent Femmes. In covering (and renaming) The Vaselines’ ‘Jesus Wants Me For A Sunbeam’, they killed two birds with one stone – indulging Cobain’s fondness for promoting obscure bands who had influenced him (he was among the last of that school of generous and genuinely knowledgeable hipsters, since made obsolete by the Internet, who delighted in championing cult music for its own sake), while incorporating what he described as “a rendition of an old Christian song”, referring to the hymn the Scottish group had spoofed.

Cobain was always a terrific singer, and on MTV Unplugged In New York he compressed his voice into a haunted rasp. This, alongside the sensitive playing of his fellow musicians, made his own songs, the earliest of which had been released four years prior to the session, sound steeped in folk, blues and bluegrass and as old as the hills. Or at least as old as the tour-de-force of a closing number, a version of Lead Belly’s 1944 arrangement of the traditional song ‘In The Pines’, which that greatest of folk-blues musicians had retitled ‘Where Did You Sleep Last Night’. Cobain knew of Lead Belly, and the song, thanks to Mark Lanegan, the Screaming Trees singer. He had played guitar on Lanegan’s own version on the latter’s first solo record, The Winding Sheet (1990) – which album was the most specific and immediate inspiration for the Unplugged recording. If Lanegan’s (superb) solo output since has at times resembled Nirvana’s record in mood and tone, that’s not him imitating them; it’s him carrying on with the idiom they borrowed from him.

When you’re reinventing yourself as the epitome of gritty, rootsy, “authentic” Americana, perhaps the least apt thing you can do is throw in an emphatic acknowledgement of all that stands in seeming opposition to that: something glam and queer and synthetic and altogether European. Which is exactly what Nirvana did; and again, this was no accident. Not only did they cover David Bowie, they covered one of his (then) more obscure songs, and certainly one of the strangest, ‘The Man Who Sold The World’.

It may be hard to conceive of today, but in the mid-1990s, David Bowie was not revered, as he is now, as the most significant single figure in late-20th-century pop. His stock was at its lowest point (not just a turn of phrase; in 1997 he would issue Bowie Bonds, effectively floating himself on the market). He was taken entirely for granted, and seen by many who had idolised him in his pomp and in their own youth as just one more old-and-in-the-way duffer, while Nirvana’s younger audience often didn’t know him at all. There are plenty of people, including some of this parish, for whom MTV Unplugged In New York was their first, teenage encounter with Bowie’s work. Always good at telling a story on himself, Bowie would later say that, although he was “blown away” to discover Cobain liked his music, and he regretted never having the chance to ask Cobain about the latter’s choice of song, he wasn’t best pleased by “kids that come up [after seeing Bowie play ‘The Man Who Sold The World’] and say, ‘It’s cool you’re doing a Nirvana song.’ And I think, ‘Fuck you, you little tosser!’”

In deliberately positioning themselves between the Bowie of 1970 and the Lead Belly of 1944, Nirvana found the link between the two: their common eerieness. There’s a certain irony in that, while British acts were slavishly retreading the sound of bygone Britain, Cobain, who sincerely adored The Beatles, would never have thought of directly copying them. He understood the difference between inspiration and imitation; that all pop music is stolen from somewhere, and what matters is not that you steal it but whether you make something new from it once you’ve got it. (This was an insight he shared with Bowie, who was perhaps the greatest shameless thieving genius of them all.)

MTV Unplugged In New York is the sound of Nirvana taking all the ground they want, and not giving an inch of it away. It’s the sound of them wrong-footing both their fans and their critics. It’s a magnificent set of songs, magnificently rendered. It didn’t make their previous albums redundant, or irrelevant: those remain formidable rock records, and the hits will be played as long as there are student discos. But nothing else they did has such breadth, or depth, or texture. Nothing else gives so full a picture of Cobain’s talent and sensibilities. Nothing else shows how artfully he could weave together pop’s contrasting strands. It almost didn’t happen. A day before the taping, Cobain was refusing to play. He made a lot of poor decisions in his all too brief time here; changing his mind on that was surely one of the best.