On January 23 1988, Michael Jackson climbed to the top of the Billboard Hot 100 for the ninth time with ‘The Way You Make Me Feel’. Meanwhile, an unnamed band from Aberdeen, a small lumber city about 100 miles to the west, arrived at Reciprocal Recording in Seattle to cut their first demo tape. Teaming up with in-demand producer Jack Endino, they blitzed ten tracks in just five hours. Though they harboured big hopes for the year ahead, those three musicians – who would adopt the name Ted Ed Fred for a show later that day – couldn’t have fit the mould of the typical act hogging the top-end of the charts any less.

Recorded and “rough-mixed” that stormy Saturday afternoon for a cut-rate $152.44, the “Dale Demo" – as it was dubbed by Endino due to Melvins’ Dale Crover temporarily filling on drums – would prove instrumental in the heady rise of the band that would finally settle on the name Nirvana two months later. Swiftly circulating the tape around a few influential heads in Seattle’s increasingly fertile scene (most crucially their future boss in Jonathan Ponemen, co-founder of the city’s indie imprint par excellence, Sub Pop) Endino would unwittingly alter the trajectory of modern music. Four years to the month and one dizzying, MTV-sanctioned, hip music rag-shagging, cognitive dissonance-inducing paroxysm later, Nirvana’s diamond-selling second album, Nevermind, knocked Michael Jackson’s Dangerous (a record produced for an unprecedented $10,000,000) off the top of the charts. The tables had turned.

Burnt-out after a gruelling seven-month world tour, Nirvana slumped down with Geffen Records in mid 1992 to discuss a proposed compilation comprising B-sides, outtakes, radio sessions and unreleased tracks from the Dale Demo. Though publicly peddled by Geffen’s head of marketing Robert Smith as an “artist development tool” to solidify the band’s credibility and give their new fans a glimpse into their roots, that was really only half the tale. Following the dazing rout of Nevermind, the release was also a ploy to “beat the bootleggers” and a means to quell rising demand for new material. Nirvana were, after all, the world’s biggest band. Despite recently having endorsed a reissue of the band’s Endino-produced, Sub Pop-released debut album Bleach, Cobain wasn’t fussed on the compilation idea initially. But when he successfully haggled with Geffen for the right to produce the release’s artwork himself – a head-to-head that he was never going to lose – Nirvana gave the green light.

With Filler and Throwaway being leaked as possible titles to the press as late as mid-November, Incesticide was compiled by Cobain whilst living in various addresses throughout the Autumn. It was released with little to no fanfare on 14 December, 1992. With the Kurt and Courtney tabloid machine edging into ever farcical territory, the frontman deliberately keep schtum about the release in the music press. Krist Novoselic, however, told Michael Azerrad of Rolling Stone that Incesticide felt like something of a way back to the source and a stepping stone to what was already in the process of becoming In Utero: "We thought it would be something nice for the fans just to see where we’re coming from. Some of the stuff is kind of wild. [It’s] maybe the step we’ll take, because the pendulum is swinging back in that direction and it won’t be that much of a shock."

Comprising 15 tracks from seven separate sessions, recorded across three years with five different producers, Incesticide was, in reality, much less a well-defined snapshot of the origins of Nirvana, and more a winding reel tracing the minor glories, growing pains, hero worship and remarkable multiplicity of a punk band who could veer between bubblegum-pop, sludge rock, sub-metallic grind and indie rock completely at whim. And unlike most compilations of its nature, it didn’t attempt to conceal any of Nirvana’s flagrant contradictions. In 1992 it was rare enough for a band to release what was essentially discarded material; with Incesticide, Cobain offered up a tactfully-presented antiphon to the staggering success of Nevermind. Luckily, just as the major league rot had begun to set in, Geffen were eager and on hand to facilitate the pre-approved “fuck you”.

Clocking in at 44 minutes in length, Incesticide blurs into view by way of a 1990 Sub Pop single and its B-side, initially released in the middle of Nirvana’s metamorphosis from Olympia contenders to global stars. Where the barrelling, bass-led strut of ‘Dive’ rumbles by via Novoselic and Chad Channing’s locked groove, ‘Sliver’ is an instant departure. Recorded with Mudhoney drummer Dan Peters, Cobain presents a masterful face-off between twee pop and fuzzed-out despair on the A-side. While Nirvana, the pop band, had previously reared their head on ‘About A Girl’ on Bleach and, in essence, at least half of Nevermind, ‘Sliver’ was an irresistible two-minute blitz of lingering childhood unease that proved that, beyond the surface drama of his life post-1991, Cobain married simplicity with punk heart and – most importantly – a hook like few others.

While a previously unreleased radio take of ‘Been A Son’, the scuzzy, overlooked punch of ‘Stain’ and a ‘New Wave’ version of ‘Polly’ hit home early on, Side A whooshes to a close via a brace of sublime deference appropriated from the band’s Australia/Japan-only EP Hormoaning. Featuring new member, the all but metronomic Dave Grohl on drums, a cover of Devo’s ‘Turnaround’ makes for a thwack of sneering wanderlust, while renditions of The Vaselines’ ‘Molly’s Lips’ and ‘Son Of A Gun’ capture the simple joy in straight-up, power-chorded, punk rock naiveté. More than anything else, those three Hormoaning covers – originally recorded for a John Peel session at Maida Vale in October 1990 – reveal a band who, even when honoring their indie heroes on the radio, seemed to stem from a place of unflinching authenticity.

But it’s Side B – particularly five tracks recorded for the “Dale Demo” – that showcases both the true, spontaneous spirit of Incesticide and Nirvana as a band pre-name, fanbase, permanent drummer or any semblance of label guidance. It reveals the first un-self-conscious lunge into the light from an act who obsessively identified with the 80s underground; a world overseen by the likes of Butthole Surfers, Scratch Acid, Flipper and their friends and gurus, the Melvins. From the sludge-metal riff fetish of ‘Aero Zeppelin’ (a title uniting two of Cobain’s favourite 70s bands) and ‘Beeswax’ to the sordid, psycho-funk of ‘Hairspray Queen’ and ‘Downer’ – a quintessential Nirvana peak that featured on versions of Bleach from 1992 – the Dale Demo hurtles from the past to offer a salvo of scuzzed-out abandons, anti-solos and larynx-shredding screams. The perennial murk of ‘Big Long Now’ and ‘Aneurysm’ only serve to seal the deal.

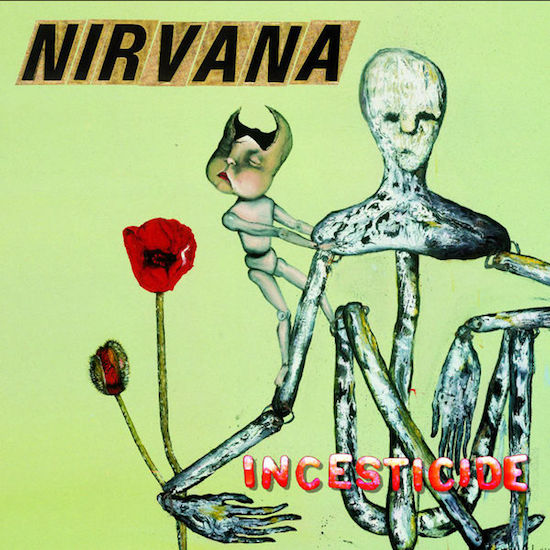

As well as carefully compiling the tracks and their order for the release, Cobain assumed the role of de facto art director and liner notes author. The contents of the latter tell its own story. In a winding, open-letter-like decree – a revised version of the original, which was essentially an open attack on Lynn Hirschberg of Vanity Fair – Cobain strenuously states his defence against being misinterpreted or subsumed by the corporate rock machine: “A big "fuck you" to those of you who have the audacity to claim that I’m so naive and stupid that I would allow myself to be taken advantage of and manipulated.” An artist addressing his audience in such a way was largely unheard of. Increasingly inaccessible due to an internal tug-o-war between ambition and validity, Cobain attempted to present the case that if Nevermind was what they were capable of, Incesticide was who they truly were.

Like its draftsman in Cobain, Incesticide is endlessly compelling in it all its shapeshifting, cobbled-together discrepancy. Reaching 31 in the Billboard 200, it would sell only a fraction of what Nevermind shifted, but for what is essentially a re-assembled punk rock record, it remains one of modern music’s success stories; an effective – whilst ultimately corporate – infiltration of the underground straight into the overground. Revealing the very DNA of a band who would never play the polished rock record game again, it shone a searchlight on the quality and depth of Nirvana as a band who navigated the full gamut of blown-out riffs, full-on eccentricity and pure pop sensibility. Better still, as a spur for what they would master on In Utero, Incesticide captured the truest sense of Nirvana as an act who were, at their very best, a great punk rock band.

As Geffen’s Robert Smith commented upon its release, “You become an overnight fan of a true punk band and you better be prepared for what comes with it." A bit antsy, sure, but he wasn’t wrong. While Cobain would paint himself as a martyr of the underground to varying degrees of success, Incesticide comprehensively lacked the shit that Nevermind gave, and therein resided its lure. A quarter of a century on, it remains a punchy, messy, giddy reminder that sometimes the growing pains and first-takes are something to cherish.