My late grandmother used to tell me to "take people as I found them." Using her words as a life rule, Nick Cave is – in my experience – both a kind and well-mannered gent. I met him in 2010, along with his fellow Grindermen as they promoted their excellent Grinderman 2 album. As a boisterous interview ended, Cave congratulated me on "not being another fucking scumbag journalist," which I’m pretty sure my grandmother would have thought a mightily kind gesture. I received the compliment (which is in the running to be the title of my terminally-unwritten memoirs – ‘Not Another Fucking Scumbag Journalist’) for not enquiring as to whether Grinderman was Cave’s mid-life crisis band. I had scrubbed the question minutes before the interview.

However, this was only the beginning of Nick Cave’s grandparent-impressing performance. As we said our goodbyes, Nick took my hand and drew me in for a manly hug. At the same time he burped. Not a huge, room-silencing belch, but a burp nonetheless. And while I accept that may have not been a brilliant example of manners, it’s what he did next that sealed the deal. Cave quickly grabbed each side of my face and moved my head away from the burp area. Nick Cave – he of The Birthday Party, The Bad Seeds and Grinderman infamy – had saved me from having to smell his gastric gas. What a gentleman.

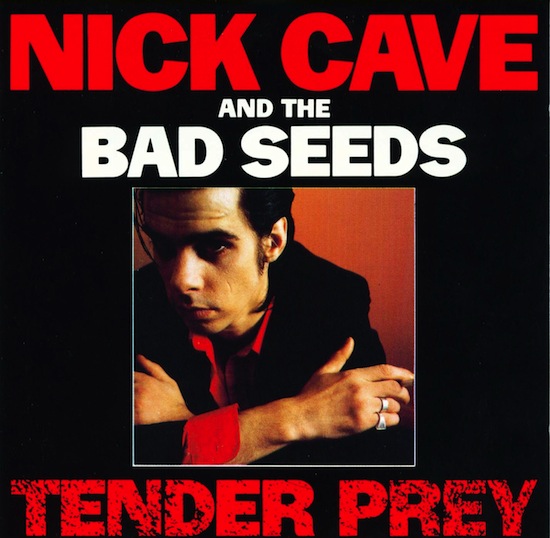

I may, of course, have met Mr Cave on a good day, but I’m willing to bet that if I’d interviewed him in 1988, he may have been less concerned about protecting my nasal passages. Twenty-five years ago, Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds released a fifth solo album, Tender Prey. It’s still, in many ways, my favourite album in Cave’s extraordinary canon of work. It was the point at which Cave seemed to really begin to trust his talent as a songwriter, as he moved The Bad Seeds further away from the gloriously savage goth-punk of The Birthday Party and his early solo work.

However, Tender Prey was made during a hugely unsettled time in Cave’s life. During its creation and recording, Cave lived is an apartment in Berlin’s Kreuzberg area and was using heroin regularly. Bad Seed guitarist Mick Harvey is quoted as describing 1987 as being "an utterly chaotic year" and that Cave’s drug use "was at its worst point and beginning to interfere with what was going on." Cave was also stretching himself to the limit creatively – he was composing snippets of songs for Tender Prey whilst also writing his debut novel And The Ass Saw The Angel and appearing in his first feature film, Ghosts… of The Civil Dead.

Somehow Tender Prey was recorded over snatches of sessions spread over a six-month period between August 1987 and January 1988 in Berlin, London and Australia. At the time, the Bad Seeds had grown to a six-piece, with keyboardist Roland Wolf and Cramps/Gun Club founder Kid Congo Powers joining Cave, Harvey, guitarist Blixa Bargeld and drummer Thomas Wydler. If the sessions were fractured and tense (Cave at one point punched engineer Tony Cohen for failing to overt a stab of feedback), alchemy was taking place – Tender Prey would prove to be a thrilling listen. "We knew we had some great things in there somewhere," Cave would later remark about the ragged recording process, "and it took a few shots at it to find them."

Tender Prey was released on September 19th 1988. The opening track is arguably one of Nick Cave’s finest moments and, from a personal perspective, would become one of my favourite songs of all time. ‘The Mercy Seat’ was, quite simply, a masterpiece. Over seven terrifying minutes, Cave told the story of a man about to be executed by electric chair. A simple piano coda, set amid piercing guitars and guttural drum samples, framed a track steeped in religious imagery, which wrestled with notions of injustice, redemption and salvation.

Lyrically, ‘The Mercy Seat’ displayed Cave’s obsessive focus and use of fabulous metaphor and alliteration. From the psychedelic death-row observation of "A ragged cup, a twisted mop / The face of Jesus in my soup" to the hellish final moments of "Into the mercy seat I climb / My head is shaved, my head is wired," ‘The Mercy Seat’ was compelling storytelling. In 2013, it still sounds magnificent. In 2000, Johnny Cash’s gentler version had already confirmed the majesty of Cave’s original composition.

Amazingly, the song’s genesis took place over several months. At the time, Cave was deep into writing And The Ass Saw The Angel, was barely sleeping and would infrequently jot down the odd idea for a song in a notebook. He would later reveal that ‘The Mercy Seat’ grew from "a little plant into something monstrous and many-headed" over a protracted period. This was typical of the disjointed way much of Tender Prey was created, with Cave initially presenting a number of tracks as minimal piano-based compositions. According to Mick Harvey "it took us a while to develop these [new songs] into something but, bit, by bit, we cobbled the album together."

And if the Flood-produced Tender Prey was "cobbled together" by a band collectively hammering all manner of narcotics, led by a heroin-addicted singer trying to juggle three major artistic projects at once, the end result was miraculously good. Over ten stubbornly virile tracks, Tender Prey re-presented Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds as masters of garage punk, gothic country and ragged blues, with lyrics laced in malevolent bombast and Catholic guilt. To my 18-year-old ears, the album sounded menacingly sexy.

In truth, ‘The Mercy Seat’ was not only the standout track on Tender Prey but also an outlier. A number of songs on the album remained piano-led and contained a burgeoning musicality. The seeds – if you will excuse the pun – for future classic albums such as 1996’s exquisite Murder Ballads and 2004’s epic double Abattoir Blues/The Lyre Of Orpheus were sown on Tender Prey. Be it on the nocturnal melodrama of ‘Mercy’ (a song about John the Baptist), on ‘Watching Alice’ (Cave’s self-confessed paean to his fascination with voyeurism) or the gentle country gospel of the closing ‘New Morning’, The Bad Seeds had rarely sounded as tender or vulnerable.

In the aftermath of Tender Prey I lapped up everything Nick Cave-related. In August 1989 I saw him give a reading from And The Ass Saw The Angel at Manchester University. It was a darkly hilarious evening. Set against the gothic splendour of the university’s Whitworth Building, Cave bounced between being genuinely funny and demonically bleak. A few weeks later I attended a matinee showing of Ghosts… of The Civil Dead at Manchester’s Cornerhouse. Cave’s performance was pretty staggering, and without wanting to offer any spoilers, his role in the film’s utterly harrowing final scene ensured a stunned silence in the cinema as the credits rolled. I remember stumbling out into the Saturday afternoon shopping crowd feeling totally unnerved. I headed to the nearest pub and drank several pints of industrial-strength continental lager in an attempt to dull the stomach-churning shock.

Cave had flown to Melbourne in October 1987 to film his role as a prisoner at a ‘super-maximum’ security facility. His interest in the film had been, in part, fuelled by his contempt for the penal system and "people deciding on other people’s fate, which irritates and upsets me." Unfortunately for Cave, he was about to have a first-hand experience of such a system. In January 1988 he was arrested for possession of 884 milligrams of heroin. Previous convictions meant he faced the real possibility of a stint in prison unless he sought medical help for his drug addiction.

Cave subsequently undertook a two-month ‘residential detoxification programme’. A short promo-tour followed during the summer of 1988, which was notable for an infamous altercation with NME journalist Jack Barron. Barron was writing a cover feature on The Bad Seeds but asked one too many question about Cave’s drug use. The singer threw a glass at him, called him – quite marvelously – a "shit eater," before punching the journalist to the ground. I remember reading about this incident in the days before my Grinderman interview. It didn’t help with my levels of apprehension and undoubtedly contributed to me scrubbing the mid-life crisis question.

But, aside from (or may be because of) Cave’s personal roller-coaster, Tender Prey was a ragtag triumph. The rousing garage pop of ‘Deanna’ would quickly become one of Cave’s best-known songs (it was almost ‘radio friendly’) and a live favourite. The track was based on a version of Edwin Hawkins’ ‘O Happy Day’ and inspired by a teenage relationship Cave had with a girl in Melbourne and the song would allow Cave to "time-travel" to happier days. Again, the lyrics were particularly memorable – "Murder takes the wheel of your Cadillac / And death climbs in the back" depicted the real-life Deanna’s zest for cruising around Melbourne in search of semi-legal mischief, while the "Ku Klux furniture" referenced the white-sheeted sofas in her parents’ house.

Elsewhere, the growling ‘City Of Refuge’ was a homage to Berlin and a track inspired by a Blind Willie Johnson song of the same name, ‘Up Jumped The Devil’ shimmied with an almost vaudevillian Delta blues vibe and ‘Sugar Sugar Sugar’ oozed primal menace. Tender Prey was released to widespread critical acclaim. Chris Roberts – my favourite music journalist of that era – described the album in his Melody Maker review as "a circumstantial classic."

Twenty-five years on, Tender Prey remains a visceral, compelling listen. Amid the chaotic whirlwind that almost subsumed Nick Cave during its creation, it was album that defined the future direction of The Bad Seeds. After completing his time at the addiction clinic, Cave gave an interview to The Face magazine during which he described Tender Prey as "one long cry for help," before revealing that he didn’t he’d been "honest about the way I feel because I’ve been totally numb – maybe all along I’ve been articulating how I should feel without feeling it." Against such an emotional backdrop, Tender Prey was a formidable achievement and the makings of an unlikely gentleman.