"It’s bollocks."

The time is a May Saturday night in Slough in 1985. The scene is the kind of house party that will force the host’s parents to question their decision to go away for the weekend. All around is evidence of the evening’s excess: crumpled beer cans, overflowing ashtrays, red wine leaving its damage on a carpet. Hapless lads are being rebuffed by girls who know they can do better, and the usual scuffles are occurring at the stereo as compilation tapes struggle to get played in their entirety.

Meanwhile, I’m enthusing about New Order’s recently released third album, Low-Life to my friend Henry and he’s having none of it.

"It’s bollocks," he repeats.

I first met Henry when I was about 15-years-old. Six years older than me, he proved to be a pivotal and influential figure in my teenage years. Another second-generation Pole, he was the kind of guy who’d seen the Rolling Stones at Knebworth in 1976 and arrived at the conclusion that rock was dying on its arse before being caught up in punk’s seismic blast. He saved my friend Chris and I from the gumby clutches of the NWOBHM and prog rock that gripped the all boys grammar school we attended by taking us to see The Birthday Party at the Hammersmith Clarendon Ballroom at the tail end of 1981, a gig so terrifying and thrilling that it radically altered our tastes and perceptions of what music could be. Chris and I ended up spending a lot of time at his place as he turned us onto bands including The Fall, Gang Of Four, Cabaret Voltaire as well The Velvet Underground and The Stooges, two bands that rightly survived that pre-1976 cull. And of course there was Joy Division, who Henry had seen in action on a number of occasions, most notably in High Wycombe and what was to be their last gig at Birmingham University.

Even as New Order were gearing up for a new phase in their career, the shadow cast by Joy Division still loomed large on the cultural landscape. Indeed, the bleakness of post-industrial Manchester that informed Joy Division’s music soon spread across the UK like a black, ominous cloud thanks to Margaret Thatcher’s administration. 1985 proved to be a watershed year. March 3rd saw the end of the year-long miners’ strike. The bitterest of British industrial disputes, the strike had seen communities torn apart and the increased levels of violence accompanying the dispute were broadcast with a sickening level of regularity on the TV news. Later in the year, both the Broadwater Farm estate in Tottenham and Toxteth in Liverpool were engulfed in terrifying riots. Sandwiched in between on May 29 was the Heysel Stadium disaster that saw 39 people crushed to death following crowd violence – an event that was broadcast live on national television and beamed into homes across the world. More than any other year, 1985 can be seen as the year that the lid was finally closed on the coffin of the optimism and liberalism that had been born in the 1960s. But not only that, the Conservative party jettisoned the idea of one-nation conservatism in favour of competition that led Thatcher to eventually declare that "…there is no such thing as society."

But if Britain was moving away from the notion of shared responsibility, so New Order were moving away from its original audience. For some people, like my friend Henry, New Order’s move to a digitised pop present was a step too far. Low-Life wasn’t a sudden manoeuvre but a cathartic conclusion that can be traced back to second single, ‘Everything’s Gone Green’, and one that saw them lose a sizeable number of the overcoat brigade. This was a gradual process as the self-produced ‘Temptation’ gave way to the game-changing dance monster that was ‘Blue Monday’. But despite the success of ‘Blue Monday’, New Order were still feeling their way. Listened to in the context of their back catalogue, their second album, ‘Power, Corruption And Lies’, was the sound of a band still striving to achieve a consistent flow over two sides of vinyl and one that can be seen as a bridging album between the under-rated Movement and Low-Life. ‘Ultaviolence’ is a technicolour sibling of ‘Senses’ while ‘Ecstasy’ and ‘Leave Me Alone’ aren’t that far removed from what preceded them.

But the signs leading up to Low-Life were firmly in evidence. Though ‘Confusion’ – co-produced by Arthur Baker as New Order fell in love with New York’s dance demi-monde – was an exercise in off-roading, then 1984’s ‘Thieves Like Us’ was New Order back on track. Perhaps not their strongest cut, and the one that sounds most anchored to the time in which it was made, it nonetheless fuses rock and dance convincingly enough to show where they were headed. But more hints were to be dropped. In August 1984, New Order appeared live in session as part of BBC2’s 15-hour Rock Around The Clock day, an extravaganza that included films, music videos, a live performance by The Cure from Glasgow’s Barrowlands and, umm… a rockalikes contest. New Order’s session from the BBC studios was simultaneously broadcast on Radio One and it’s hard not break into a nostalgic smile when reading the Beeb’s helpful and informative blurb on the event: "A rare chance to see this celebrated cult band… For the best effect, viewers with stereo R1 should turn off TV sound and position their speakers on either side of the screen, but a few feet away. Stereo headphones provide a suitable alternative." Auntie’s charm aside, the session, which included performances of ‘Age Of Consent’ (complete with some howling off-key guitar from Barney), ‘Blue Monday’ and ‘In A Lonely Place’ among others, acted as the broadcast debut for the as-yet-unreleased ‘Sooner Than You Think’.

What was also striking about the performance was the change in New Order’s image. As The Cure played Glasgow later that night in all their goth finery, Robert Smith’s hair resembling the after effects of a comedy bomb a la Wily E Coyote, there was New Order looking as if they were on a Club 18-30 holiday: Barney in shorts and tank top, Hooky in a vest and tracky bottoms, Gillian’s white dress and Stephen Morris dressed for the Ivy League. Of course, their change in image had already been seen in interview photos where the band had been shot lounging in the sun by an outdoor swimming pool – a truly exotic concept in mid-80s Britain where the closest you’d get to this were municipal lidos, hardly the height of glamour. In the then-rarely seen video for ‘Confusion’ (remember: these were the days when you’d sit in front of your television to press ‘record’ on the video recorder so you could watch these things again – and video tapes weren’t cheap). Broadcast live in national TV, this was the first time many New Order fans saw where the band was at and it drew a firm line between their colourful present and the monochrome past.

With the benefit of hindsight from the vantage point of 31 years, one senses some tension between Barney and Hooky (they barely look at each other) and it’s tempting to read more meaning than there probably is when Barney sings, "Well we had a party in our hotel last night / It ended up in an awful fight / My friend left me and my heart too / I hope I don’t end up like you"

But there were to be other pointers that New Order were putting the past behind them. ‘The Perfect Kiss’, itself played live as early as May 1984 at the Royal Festival Hall in London, was the first time that New Order lifted a single from an album. To contemporary mores this may appear to be no big deal, but 35 years ago it provoked some to throw arms up in horror. Up until this point, both New Order and Joy Division had released stand-alone singles while the albums remained separate entities. Was this an indicator that New Order, and by extension Factory Records, were now playing the pop game? Certainly for fans of a particular vintage, the move smacked of commercialism and cries of "Sell out!" were raised. But then again, it made perfect sense; New Order always were a contrary beast at the best of times and what could be more perverse then seemingly playing the game? There may also have been more practical concerns at play. Many casual pop buyers felt cheated with their copy of Power, Corruption And Lies, an album that not only had no song titles – or any information for that matter – on the cover, it also didn’t contain ‘Blue Monday’. Then again, Factory Records rarely took out adverts in the music press, largely due to budgetary constraints rather than for aesthetic reasons, and so it was that much of their output was either discovered by accident in record stores or specifically asked for after a play on John Peel’s late night Radio One show.

Sell-out or not, what was being overlooked was that New Order had mastered the art of the 12" vinyl format. So many 12" singles of the early to mid-80s consisted of little more than the original version of the track with a whacking great drumbeat breakdown around halfway through that went on for far too long before kicking back in to the original piece. All well and good if you were a DJ but not so good for pop kicks. As became apparent when Low-Life finally hit the shelves was that the album version had been reconstructed and not the other way around. Here was an extended piece that took advantage of the format and allowed the band to really stretch out into new territories. Slap bass intro? Check. Juddering synths? You got it. A frog chorus? Move over, Macca! Yet despite their best efforts, ‘The Perfect Kiss’ only reached the heights of 46 in the UK singles charts. Even though ‘Blue Monday’ had become the biggest selling 12" of all time, New Order were still regarded as a cult concern and so radio exposure was largely restricted to evening play.

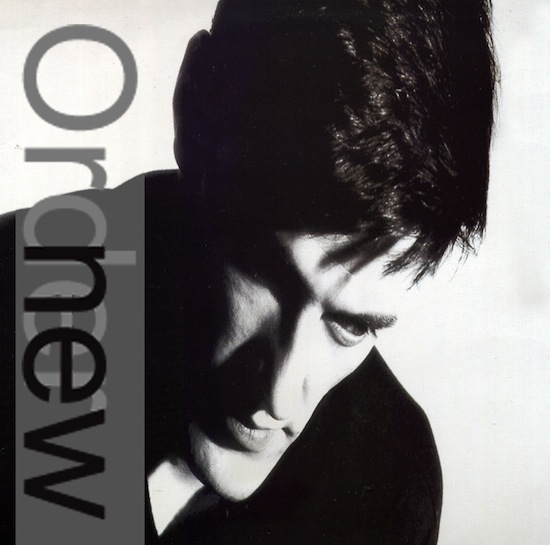

When Low-Life finally appeared in May 1985, New Order’s break with its past was firmly in evidence before the needle hit the record. The cover art stunned on more than one level. One of designer Peter Saville’s most ambitious and celebrated creations, the elaborate sleeve was swathed in tracing paper, an artistic execution that at once separated both New Order and Factory Records from its peers and rivals. But what also proved staggering was that the images of Stephen Morris and Gillian Gilbert adorned the front and back covers respectively. Superimposed over both were the band name and the song titles. Having been used to a series of album and single covers that did little to give anything away, here was another first for New Order: specific surface level information. That it was wrapped in such an inventive and original fashion proved that whatever their game plan was, it was still to be executed on their own terms. Moreover, the artwork was an artifact in its own right that would stand proudly against and with the music that it housed. At the heart of the package is the vinyl and the treasure contained within its grooves, and enveloping that is the inner sleeve which, in an almost comically prescient execution – or is it simply the benefit of hindsight? – finds Barney and Hooky on opposite sides of the cover. To encounter Low-Life for the very first time was a thing of true wonder; this bold cover would almost taunt you all the way back from the record shop as you rushed back home as quick as you could to see if the sound matched the ambition of the vision.

That it did. Those four snare whacks that usher in ‘Love Vigilantes’ serve notice on something entirely fresh from New Order. This is a tight sound buffed with a touch of reverb and the music that follows is new ground for the band. Gorgeously lush, the headlong rush of melodica, synthesised low end, Hooky’s twanging bass and acoustic guitar are unlike anything that New Order has attempted before. It’s appeal is immediate, at once familiar yet something demanding your acquaintance. This is the point where Barney finally finds the right pitch for his voice; previous records had found him delving into a lower register while others saw him straining to reach higher notes but here he’s clear and confident. As exemplified by the instrumental coda, the band simultaneously embraces and transcends its influences. Those clipped and chopping guitars make more than a passing nod to the rhythmic and funkier playing of The Velvet Underground, a band whose influence was reinforced by the release of their VU album just a few months earlier, but for sheer goose bumps Hooky’s gloriously swooping bass break is hard to beat. This is a superb inversion of the rock idiom in that the low-end instrument takes the lead while being underpinned by the guitar, keyboards and drums.

The truncated version of ‘The Perfect Kiss’ stands in stark contrast to what had preceded it yet despite its overt pop and dance overtones it still fits like a glove. There’s comfort to be had in Hooky’s bass as all around sequencers and programmed drums leap into life and urge feet on to the dance floor. ‘This Time Of Night’ follows in similar fashion albeit more maudlin and languid and what’s evident is New Order’s ability to stretch out and explore the technology at their fingertips as well as their song writing chops. It’s an exercise that’s repeated later with ‘Sooner Than You Think’ and in both instances New Order fuse their modus operandi to date while reaching to a future that’s brought convincingly into the present.

But it’s the mix of styles that makes Low-Life such a joy. ‘Sunrise’ finds New Order rocking out once more, driven along by some of Hooky’s most compelling and memorable bass work and Barney’s almost franticly ascending guitar licks. And yet Low-Life‘s most idiosyncratic moment makes nods to the most unlikely of sources. The instrumental ‘Elegia’, which opens the second side of the album, has more than faint echoes of the influence of Ennio Morricone, specifically ‘La Resa Dei Conti’ from For A Few Dollars More and The Good The Bad And The Ugly’s climactic ‘The Trio’. The scene is transposed from Almeria to Manchester but the epic sweep and grandeur of New Order’s efforts effortlessly match Morricone’s elegiac pieces. The music grows in stature as the track progresses, first from gentle tinkles to Hooky’s mournful and yearning bass playing that gives way to reversed cymbals and ever present arpeggios and some filthy guitar playing towards the climax. From the vantage point of 2015, ‘Elegia’ can be viewed as antecedent of New Order’s limited edition 2003 release, The Peter Saville Show Soundtrack. It wasn’t until much later that ‘Elegia”s full length – 17 minutes – became apparent via bootleg recordings and it was finally given am official release as part of the 2002 boxset, Retro. Titled as perfectly as it was executed, ‘Elegia’ is a fitting tribute to the late Ian Curtis.

‘Sub-Culture’ is the album’s most overt disco moment and probably the cause of the overcoat brigade’s decision to part ways with the band. A subsequent remix of the track by electro producer John Robie was released later in the year and was met with howls of derision from long standing fans who felt that it strayed too far from what was expected of the band. Designer Peter Saville reportedly hated the mix so much that he couldn’t be bothered to create a sleeve for it, hence the plain black packaging. Given such resistance, it’s hardly surprising that ‘Sub-Culture’ limped to number 63 in the UK singles chart.

Low-Life ends as joyously as it starts. ‘Face Up’ bears more than a passing resemblance to ‘Temptation’ but the galloping force with which it’s delivered gives it it’s own identity. Stephen Morris’ drums are huge and the snare hovers over the threshold of distortion as it drives and marshals the instrumentation around it. The perfect fusion of New Order’s rock and dance sensibilities, that fact that this wasn’t released as a single instead of ‘Sub-Culture’ remains as mystifying now as it did 35 years ago.

Even with the passing of 35 years, the question of Barney’s lyrics still loom large and the answers remain divisive. They certainly lack the mystery of their earlier efforts and, as in the case of ‘Love Vigilantes’, follow a straightforward linear narrative. Whether a lyric like, "With our soldiers so brave/Your freedom we will save/With our rifles and grenades/And some help from God" is intentionally hilarious or not is still a moot point but their sense of wide-eyed humanity is undisputed. Similarly, ‘The Perfect Kiss’ veers from a kind of naivety to something quite touching. But what is certain is that once again New Order were making a firm break from their past.

Or were they? By the end of the year, New Order seemed to have come full circle. On December 7, 1985, New Order played the Slough Fulcrum, an entertainment centre on the brink of closure. That it was ready to close its doors came as no big surprise to Slough’s residents, such was is its constantly poor programme of entertainment. Yet the moment its imminent demise was announced, a series of gigs were announced that saw the venue more packed than it had ever been. The Cult filmed the live sections of their ‘Revolution’ video there (the memory of goths being knocked off shoulders by swinging boom cameras still raises a chuckle) and Siouxsie And The Banshees paid a surprise visit. But the biggest raiser of eyebrows and cause of much excitement was the appearance of New Order.

The gig was memorable for a number of reasons: previews of the yet-to-be released ‘State Of The Nation’ and ‘Weirdo’ and a pony-tailed Peter Hook lashing out with his bass guitar at some wag who’d called him a "hippy" spring to mind but what truly lingers is the encore. Not only was an encore something of a rarity in those days for the band, it was the choice of material. A sizeable number of the crowd had left after set closer ‘Temptation’ but there remained a large enough throng baying for more. Amazingly, New Order returned but what caused jaws to drop was the instantly recognisable drum intro to Joy Division’s ‘She’s Lost Control’. The sense of disbelief throughout the venue was palpable and to cast a glance at the back of the place was to see excited fans pushing past the bouncers and running in from the foyer with a barely contained sense of delirium. And here they were – the technicolour New Order dipping into their black and white past as they acknowledged their history and heritage.

This was a typically perverse move by New Order but for the overcoat brigade it was too little, too late. Not that it really mattered. Even as Joy Division the band refused to play the game and they weren’t about to start now by living up to other people’s expectations. Low-Life was the point that the past and the future blended into something new, a demarcation point that saw the start of an ascension that until then had only been fleetingly hinted at. This was pop, rock, dance, disco and so much more colliding in a glorious explosion of colour and thrills, a feeling of unrestrained ecstasy that proved that the only rule is that there are no rules. New Order would never be the same again and, by extension, neither were we.

Bollocks? Bollocks to that.