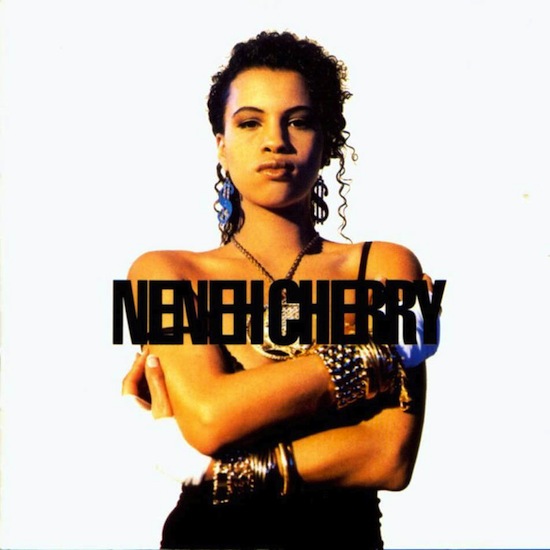

When the video for ‘Buffalo Stance’ first appeared in 1988, it seemed raw and almost ugly, with its harsh noise set against yellow and purple psychedelia. The artist herself, Neneh Cherry, was equally unaccountable. Here was a singer with a vaguely New York drawl and the odd Cockney riff, who seemed unplaceable in terms of character as well as nationality. She scowled as she rapped, her juicy foul mouth pressed close to the camera. According to the lyrics, the object of her scorn was a pimp who had tried to recruit her. Yet Cherry was just as dismissive of everyone else on the street: the "nasty" girls with permed hair, the weak-willed boys who came running when called. The cacophonous mix of samples and tribal beats suggested a portrait of street life, with an unforgiving narrator breaking the scene down to its tawdriest details.

Even today, Cherry remains one of the most disorientingly eclectic of artists. On her debut album, Raw Like Sushi (1989), most of the tracks are catchy yet confusingly dense, throwing us off with their mood changes and far-flung references. Her voice switches nationalities within a single breath; she can come across as a sage or a brat, sophisticated or cacklingly malicious. Her tough persona implies a straightforward approach to her craft, but what the music presents is harder to decipher.

On the first track, ‘Buffalo Stance’, Cherry already comes across as a fully formed artist: powerful and casually multicultural, as we might expect from an African-Swedish singer raised in Yorkshire and Long Island. But Cherry is no "minority" demanding to be empowered: this is a performer who originates a new sound without asking for permission. Her voice immediately assumes a central position; there’s no sense of her breaking through from the margins. Her first act as leader is to call out the members of her team: first, the hi-hat, then the tambourine, and finally the DJ and his records. It’s as if, before the track can begin, each circle has to be set spinning within the Cherry universe, and she is in a position to control all of them.

When we get to the critique of the pimp and the girls, Cherry’s voice is superior and strident; throughout the album, there tends to be a view of boys as dominated and unripe, while the girls are predatory, standing around "wearing padded bras, sucking beer through straws." Men may be limp, but these young women are even less sensual, with their lacquered lips pursed over a can. So this first part of the song is rather abject, with its hawking voice, and its allusions to gross female display.

But ‘Buffalo Stance’ is a song of many moods, as Cherry goes on to alternate between anger and softness, anti-materialism and a high fashion attitude. A rising synth figure bubbles us up to a heavenly chorus ("No money man can win my love/ It’s sweetness that I’m thinking of") which shows a rare tenderness in the narrator. Even though the track has been unrelenting up to now, the bubbling and the melody expose an underlying effervescence.

We don’t get to coast on this feeling for long; the second time the chorus appears, Cherry re-armours herself and reveals that she is not alone: instead, she is part of a hip fashion elite (Cherry and producer Cameron McVey met as models in London, after all). Despite the romantic message of the chorus, the Buffalo are a catwalk crew, for whom glamour comes first ("Looking good’s a state of mind"). To emphasise the point, Cherry seizes and recharges the end of the phrase, shouting fiercely, "State of mind, don’t look behind you!/State of mind or you’ll be dead!" This creates a feeling of whiplash, as if the line has been picked up and thrashed loose.

Abrasive effects like these define the song, as well as the album. Cherry and McVey’s style is not the warm, full-bodied sound of R&B: it has a much more inorganic feel, favouring fizzy noise over the deep tones of funk or soul. ‘Buffalo Stance’ has a coiled, compressed sound; beats form little eddies and bubbles which correspond to the blooming digital shapes of the video. The synth is thin and airy, evoking something crude and mass-produced: that’s what makes the track distinctive rather than generically tasteful. Audiences may expect great music to be rich and rootsy; Raw Like Sushi remains strange because its sound is exactly the opposite – bright, sharp and cold, a rejection of the past.

The album’s second track, ‘Manchild’, also seems curiously mechanical at first. The title character is a guy with a run-down car, a cheating girlfriend and no willpower, so it’s not surprising that we get a hypnotic sense of draining away. The strings have a repetitive, droning sound; they move gradually up or down a tone, so that the entire song seems to be slipping down a slope. A program of beats forms a continually revolving and reversing pattern, and the track feels as if it’s shuffling or rotating by degrees (the video ingeniously matched this idea of constant slippage by showing Cherry surrounded by tilting levels of water). However, what’s elating is the way that the song repeatedly threatens to lose its motor – and then regains it, by a whisker. All that downward movement should lead to a dead end, but just before momentum runs out, the vocal lifts to even out and stabilize the track. The lyrics are self-reflexive; the phrase "Turn around, ask yourself" is used as a pivot, a chance for the song to do a 180-degree turn.

In terms of rhythmic structure and surprises, ‘Manchild’ may be even more of a feat than ‘Buffalo Stance’; it is astonishing in its intricate raps which upend themselves midway. Cherry plays with syncopation, sometimes teasing out words or topping a dense phrase with light notes. The track ends unexpectedly when all instrumentation vanishes, leaving a single phrase in the foreground; the final words we hear are, "’Cause I believe in miracles and words in steady doses." That last line really is a concentrated dose, as a continuously chugging rap suddenly stops, revealing that the whole song is a closed circuit.

The next two tracks are more conventionally melodic, yet both contain sublime moments in which sonic effects absolutely coincide with the subject of the lyrics. ‘Kisses On The Wind’ is a paean to a girl whose breeziness enchants the young neighbourhood boys. Her presence is reflected in the salsa rhythm, Spanish dialogue and the flowing feel of the whole song. The melody keeps billowing upwards ("More like a woman, she walks like one") and is thus subtly suggestive of the female shape. ‘Inna City Mamma’ is unusual for Cherry in that it sticks to one city and one genre: NYC blues. What makes this particular take compelling is the way that the instrumentation works with the theme of masochism: the bassline keeps coming back for an extra note, while the drums return to give one last tap. It is as if the narrator is attempting to close the book on a subject, but she can’t leave well enough alone, and the song trails into a smoky finish.

As the fog from the last track clears, what emerges is the beginnings of ‘The Next Generation’: perhaps the most puzzling and original Cherry song, full of spite, vigour and low-life humour. This is a bawd’s song, in which Cherry performs multiple characters: a bully who comes with her own cheer squad, a sarcastic girl who calls you "honey", and a mother whose lap is open to all children. As the sounds of birds flutter past, there is the sensation of a vibrant, open market, but it soon becomes ominously clear that this is actually a black market, a baby market. Fertility has turned to rampant breeding – of the rank, putrid kind. A couple of Japanese and German phrases open the song, and although there are no ethnic slurs, a kind of leering potential for racism is present. The "sensible" Cherry persona is sickened by the thought of a baby wrangler, but her voice then takes on the personality of the peddler, salivating over provocative racial combos ("Black babies, white babies/Quarter Puerto Rican, two sixths Chinese.") In this new world, she envisions babies and their ethnicities being divvied up according to value. Cherry’s maternal character is disapproving, but the bawd can’t resist a dig at this epidemic; she reacts with gasps of shock and faux-delight. She has a coarse, derisive laugh which the song then turns into a sample, unsettling us further.

Overall, ‘The Next Generation’ is a celebration of birth, creativity and fecundity, but as Cherry knows, a song about the miracle of life would make for a pretty boring cut. So she goes into the most squalid aspects of procreation: the filth of reproduction, a world of diapers and diseases. "Push-push-push" shows that the whole impetus of the song is the birth movement: the pressure of the sex act and the mother’s motion in expelling new life. The song builds a joyous cycle out of all these noises and gestures, backed by a panorama of free jazz and zoological sounds. We can picture the song’s setting as an arena, in which vivid characters whirl around while Cherry sits as the earth mother, bouncing a baby on her lap. Still, this loosely connected jig requires some sort of ending. Will the song finish on a humanist note, or will it trail off to imply endless procreation? Nothing so predictable. Towards the end, a drumline has the effect of lifting Cherry to the podium, where she asks us, "Ain’t that right?" At that, the sound immediately reduces to one beat, skating off and skipping back before Cherry laughs and says confidently, "Right." The rhythm doesn’t resolve or repeat; all sounds bounce back to the singular voice at the mic.

And that’s the substance of the album: five extraordinary tracks, several intriguing numbers (‘Heart’, ‘So Here I Come’), and a couple of middling ones (‘Love Ghetto’, ‘Outré Risqué Locomotive’) which prefigure Cherry’s next two albums, Homebrew (1992) and Man (1996), in that they are much more homogenous, rooted in a single mood and identity. Cherry is at her best when her persona seems conflicted, dividing into multiple voices and moving through different tones with exhilarating speed.

Although she clearly draws from a wealth of cultural influences, Neneh Cherry has never been anything so wholesome as a "world" artist. Released at a time when both hip-hop and sushi were considered alternative, this album still stuns with its unique take on rawness: not the fuzzy lo-fi kind, but a sound which is actually grating and alarming to the ear. Raw Like Sushi is proof that great albums don’t have to take on heroic structures; the record’s most distinguishing feature is its exploration of superficiality and tackiness on both sonic and verbal levels. Instead of a sense of grandeur or orchestration, transcendence is achieved through an accumulation of small detail: a sampled screech, the odd tinny note, an image of tiny-mouthed women sucking through straws. Soulful phrases are combined with synthetic textures, so that each sound retains its own idiosyncrasy, rather than being refined into a whole.

‘The Next Generation’ might be the ultimate Cherry creation in that it manages to fire up so many contradictions: the life process and decaying sexuality, inclusiveness and bigotry, a huge song cycle made up of chaotic, individual sounds. In this track, above all others, she proves herself an artist with the courage to bypass notions of taste and cohesion. Balanced with an epic vision of the future is an appreciation for the cheap, the sordid and the perverse: these are the kinds of contrasts only Cherry can keep in play.

Neneh Cherry plays Field Day on June 7th 2014. For tickets and information, please go here