Steven, Steven, down we go together. As a teenager my walk to school would take me past the childhood home of the lead singer of my favourite band at the time, The Smiths. Every morning, as I schlepped past the nondescript semi-detached house on Kings Road in the grey Manchester suburb of Stretford, I’d glance at the windows, hoping to catch a glimpse of a bequiffed silhouette. I never got lucky. In 1986, Steven Patrick Morrissey didn’t seem to spend any time gazing out of his parents’ abode at 8.30 on a weekday morning.

I loved The Smiths – when the best band in the world comes from your town it would’ve been daft not to – but stopped short of rabid fanaticism. I never chained myself to the railings of the ‘Cemetery Gates’ on Barlow Moor Road in Chorlton and my only pilgrimage to the Salford Lad’s Club was a recent trip to escort tourist friends. And while I cannot ever remember locking myself in my bedroom surrounded by the work of Oscar Wilde or Joe Orton, I was hugely moved by the tenderness of Morrissey’s words and became captivated by their scorchingly magnificent canon of three-minute pop songs. If I met someone who thought The Smiths were ‘miserable’ I immediately dismissed them as an idiot (and subconsciously still do, deep down in the most judgemental and obnoxious area of my soul).

And while Morrissey himself was an indirect life guru during my gangly teenage years, I knew people who really worshipped him. A close pal of mine formed a friendship with Mozzer to the extent that he would send her beautiful and thoughtful postcards while The Smiths were on tour – a level of connection that made me feel as if I was missing something, and therefore rendered me unable to make that last leap into super-fandom. This detachment meant that in 1987 I was (uncharacteristically) savvy enough to be not overly upset at the demise of The Smiths. I liked the idea of them stopping while they were still brilliant.

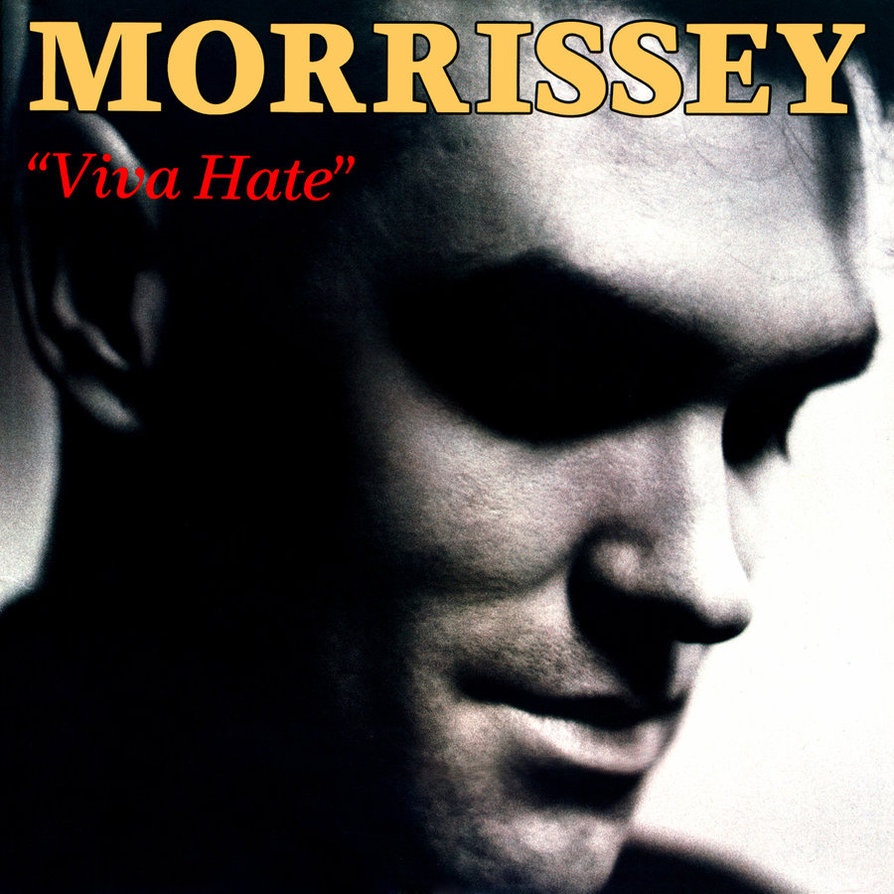

It also meant that in the spring of 1988 I approached Morrissey’s debut solo album, Viva Hate, with a relatively objective mind. I wanted it to be good, but wouldn’t have drowned myself in a sea of gladioli if it had been a steaming pile of cat sick. In fact Viva Hate turned out to be, in parts, a very decent album and was perhaps better than us Smiths fans could have hoped for. It contained four or five genuinely fabulous tracks and suggested a rosy future for the Stretty crooner.

But in the intervening quarter of a century since the hope proffered by Viva Hate, being a card-carrying Morrissey fan has become an increasingly arduous task. Musically, I don’t think he’s produced anything since Viva Hate that could quite touch the heights of ‘Everyday Is Like Sunday’ or ‘Late Night, Maudlin Street’. That in itself is not a cataclysmic crime – I’ve never expected a musician to be constantly brilliant over a 30-year period. However, set against a number of well-documented controversies that (at worst) raised the spectre of xenophobia, coupled with an almost over-bearing cantankerousness, it’s hard not to conclude that Morrissey is less relevant in 2013 than he was when embarking on his solo career. And, with hindsight as a tunnel-visioned tool, the problems were already apparent on the much loved Viva Hate.

It was Stephen Street, the co-producer of a number of The Smiths’ records, who played a central role in kick-starting Morrissey’s solo career. As the split played out, Street sent the singer a tape of demo recordings intended as potential B-sides for the band’s last singles. In August 1987, Morrissey wrote a letter to Street (a copy of which can still be viewed at the producer’s official website) in which the Mozfather concluded that The Smiths should be "laid to rest" while expressing a desire to record under his own name.

Thereafter, the project moved quickly. Viva Hate was recorded during the final months of 1987 at the same Wool Hall studios in Bath that, only six months earlier, The Smiths had recorded their last studio album Strangeways, Here We Come. Street played bass and also had the nous to recruit The Durutti Column’s guitar virtuoso, Vini Reilly. A session drummer, Andrew Paresi, completed the line-up.

The recording sessions were an odd mix of artistic tension (Morrissey was under considerable pressure to deliver a batch of songs to his new record label EMI, while Reilly and Street would constantly squabble over technical aspects) and puritanical pursuits. The stereotypical take on rock star debauchery was replaced with regular gym and sauna sessions and healthy eating courtesy of Mozzer’s vegetarianism.

However, as the title suggests, Morrissey’s debut album was fuelled by negative emotion as he grieved for the loss of his beloved band. At the time he would describe hate as being "omnipresent", and suggested in one interview that "hate makes the world go round". It must have been an exhausting way to live – viva hate indeed.

If Morrissey would subsequently conclude that Viva Hate felt "rushed", it still managed to harbour several of his greatest ever solo songs. Lead single ‘Suedehead’ was a gem – an instant dose of salvation for distraught fans of The Smiths. Featuring a classic Mozzer vocal delivery, Reilly’s iridescent guitar (however, an obstinate Vini would refuse to play the middle section solo, citing it to be "too easy") and Street’s libidinous bassline, ‘Suedehead’ was a joyride of simmering sexual tension. The song may also have been in part about Johnny Marr. A ‘suedehead’ was a grown-out skinhead favoured by bovver boys in Richard Allen’s 1971 novel Suedehead, and for a period during The Smiths’ latter years, Marr apparently pined for a "motorbike and a suedehead" coiffure.

In fact it was easy – and slightly over-romantic – to pick apart much of the words on Viva Hate as being inspired by the spilt of The Smiths, with ‘I Don’t Mind If You Forget Me’ and ‘Break Up The Family’ being the easiest to (mis)interpret. I quite liked the notion of Morrissey bouncing between love and hate for his former bandmates, as he carved out the album’s lyrics through an almost overwhelming anger. However, on 25 years of reflection, there is also a large wedge of compassion and nostalgia on Viva Hate – I still swoon at the utterly beautiful 100 seconds of chamber pop perfection that is ‘Angel, Angel, Down We Go Together’ and love the sepia-tinted ‘Little Man, What Now?’

And aside from ‘Suedehead’, greatness was close at hand. ‘Everyday Is Like Sunday’ was a wonderfully evocative classic pop song, on which Morrissey picked through the bones of a "silent and grey" "seaside town / they forgot to bomb," which must have gone down like horse DNA in a veggie burger with the English Tourist Board.

Even better was the expansive grandeur of ‘Late Night, Maudlin Street’, the album’s astonishing centrepiece and a track that mourned a lost and desperate youth over seven gorgeous minutes. I also loved the horny opener ‘Alsatian Cousin’, on which our spurned hero asked "Were you and he lovers?/ And if you were, then say that you were/ On a groundsheet under canvas / With your tent-flaps open wide," thus sexing up any experience I had of camping, which always seem to include a leaking tent and a dead-of-night stagger across a field to find a toilet. The song contained a bassline modelled on 23 Skidoo’s ‘Coup’ (possibly via ‘White Lines (Don’t Do It)’) and the instrumentally diverse album painted a notably different sonic picture to much of The Smiths’ work.

Frustratingly, but perhaps understandably given the circumstances in which it was created, Viva Hate was notable for huge swings in quality. Much of the second side was instantly forgettable. While I liked the weary contempt on the closing ‘Margaret On The Guillotine’ with its "When will you die?" refrain focusing Morrissey’s anti-Thatcher venom, the spite-soaked song only worked because of a general contempt for its tyrannical subject matter.

However, the lowest moment on Viva Hate was the risible ‘Bengali In Platforms’. First up, it was a truly terrible song from a musical standpoint. On first listen it almost produced a cattle prod of shock for those who had become used to The Smiths’ relentless brilliance. But it was the controversial lyric – the song is about the said Bengali’s attempt to integrate into a new culture – that centred around the line "life is hard enough when you belong here" that caused such a stir.

Personally, I believe ‘Bengali In Platforms’ to be more about the struggle of the outsider (a recurrent theme in Morrissey’s lyric writing) rather than an explicit comment about race. However, by choosing to use that particular line Morrissey invited the possibility for misinterpretation. This did him no favours – I felt the same about the 1990 single ‘November Spawned A Monster’ and the use of the word ‘monster’ on a song that sought to articulate the plight of people living with disabilities. I get that Morrissey wants to challenge his audience, and cherish and respect him for that, but ‘Bengali In Platforms’ spectacularly missed the mark. And, unfortunately, it is now virtually impossible to judge the song in isolation in light of Morrissey’s later – and very well documented – xenophobic statements.

Twenty-five years on, my take on Viva Hate is that while it contained some fantastic songs, they were undoubtedly the cream of the initial batch of demos that Stephen Street first presented to Morrissey, and that a mixture of the singer’s desire to throw himself into the project and Vini Reilly’s stellar musicianship created several nuggets of greatness. I often wonder what might have happened if the Morrissey-Street-Reilly axis had continued to make music (sadly, Morrissey and Street quickly became embroiled in a legal dispute about production fees).

After Viva Hate Morrissey stumbled and fumbled his way towards 1991’s poor Kill Uncle. He’s since released a number of good albums – I’d pick 1992’s Your Arsenal and 2006’s Ringleader Of The Tormentors as high points – but the truly great songs of his solo career require a degree of forensic excavation. Compared to The Smiths – and I was 12 when their first single was released – Morrissey’s solo career is as disappointing as it is perplexing.

There is still part of me that still loves Stephen Morrissey. Even as a non-vegetarian I was enthralled by his recent refusal to appear on an American TV show because his fellow guests were self-confessed duck killers. I admire his passion and honesty and his disdain for many aspects of the modern world. But, a lifetime of world-weary bitterness has soured the soul of Morrissey. This makes me sad, especially when one of his songs genuinely shook my self-centred 16-year-old self. In 1986 I was deeply affected by ‘I Know It’s Over’ from The Queen Is Dead and the lines "It’s so easy to laugh/ It’s so easy to hate/ It takes guts to be gentle and kind."

It would appear that, for Stephen Morrissey, hate will always be very much alive.