“The women came to see me. The men hated me. On Saturday morning when the men done stayed out all night Friday night, the women would be doing Saturday chores playing Millie Jackson….. You didn’t come in last night? Too damn bad, you’re gonna hear Millie Jackson!”

Millie Jackson, speaking to Soul America

Oh what a tangled web we weave,

When first we practice to deceive.’

Sir Walter Scott, ‘Marmion’

On 1 June 1974 the NME published their all-time top 100 albums, with The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band predictably sitting atop the chart. But the presence of female artists was pathetically scarce. Carole King’s Tapestry was the highest entry at 26, the incomparable Joni Mitchell came in at a lowly 67 with Blue (debut Song To A Seagull reached 84). Grace Slick’s Jefferson Airplane sat at 77 with Crown of Creation, while the Janis Joplin-fronted Big Brother scraped in at 91. Only one woman of colour appeared, Aretha Franklin at 65, lazily, with Hits, a compilation rather than one of her bona fide classic long-players. There were other glaring omissions: Nina Simone, Irma Thomas, and Billie Holliday’s Lady In Satin to name a few.

The same year this oversight hit newsstands, Millie Jackson’s Caught Up hit record shelves. It was a testament to black female mastery of 33rpm, a concept album that actually cohered, instantly surpassing much of the stodgy orthodoxy selected by the NME. Radical reinterpretations of pre-existing songs and new originals were woven together to create a clear, continuous narrative chronicling a stormy love triangle, the first side dedicated to the viewpoint of a married man’s lover, the other telling his wife’s story. Jackson’s fourth album, it refined themes running through her already august output, reflecting a soul music that had grown increasingly sophisticated and emotionally intense, neatly compressing much of where it had been, and where it was heading.

Born in Thomson, Georgia, Jackson had lost her mother early, been briefly raised by her grandparents, before moving in with her father, who remarried several times. Relocating to New York, her first foray into music had been impromptu, an open mic night one Thursday at Harlem’s Psalm’s Café. Following a stint touring with Sam Cooke’s brother LC, she issued 45s in 1969 on MGM via Suron Productions. On ‘My Heart Took A Licking’ (‘But It Kept On Ticking’) she’d arrived, baring love-wounds on a survivor’s thick skin

Feet remained firmly on the ground, for years she kept her day job in NYC’s garment district as assistant supervisor of shipping at Kimberly Knitwear, taking advantage of wholesale discounts for stage attire, joking in 1980 she was still on leave. By 1971 guitarist/songwriter Billy Nicholls had brought her to Spring Records, where she cut her self-titled 1972 debut. Producer Raeford Gerald largely called the shots, with Invictus-style confections (‘Ask Me What You Want’, ‘My Man, A Sweet Man’), catapulting her onto Soul Train. But Jackson’s DNA emerged on co-write ‘A Child Of God (It’s Hard To Believe)’, surveying a world far from redemption, in the year of Aretha Franklin ’s Amazing Grace, with a spoken intro. Hard-hitting realism entered the bedroom too on the scorching ‘Strange Things’ where a sexually dissatisfied female tears strips off her two-timing lover.

1973’s follow-up It Hurts So Good plunged fully into the deep 70s and deep, deep soul. Breakthrough title track, featured in blaxploitation flick Cleopatra Jones, revelled in the same kind of pain/pleasure filling disco dance floors circa 73-4 (Zulema’s ‘Giving Up’, Gloria Gaynor’s ‘Honey Bee’), setting it against a gritty, street-level backdrop elsewhere (‘I Cry’, ‘Hypocrisy’, ‘Two Faced World’). This was love in the real world, not the singer-songwriters’ Laurel Canyon idyll. Her approach already felt semi-conceptual, tackling love from multiple viewpoints. On the title track of 1974’s I Got To Try It One Time she’s the cheating lover, on opener ‘How Do You Feel The Morning After’, she’s the wronged wife. There were no easy judgements.

Jackson had become renowned for onstage monologues; explicit ‘raps’ Spring had been wary of committing to vinyl. However, impressed with Brad Shapiro’s recording of Jackson live in Detroit, they green-lit spoken word segments on her forthcoming album, Caught Up. Shapiro (Wilson Pickett, James Brown, Betty Wright), on board since It Hurts So Good, would co-produce with Jackson. Self-managed, she was now in total control, selecting and composing Caught Up’s material. Decamping to Alabama’s Muscle Shoals Sound (additional recording was done at Miami’s Criteria), they first cut a near 11–minute suite already in her stage repertoire, retelling Luther Ingram’s 1972 tale of infidelity ‘If Loving You Is Wrong, I Don’t Want To Be Right’, from his extra-marital lover’s viewpoint, splitting it wide open with her jaw-dropping soliloquy ‘The Rap.’ Asked what followed this electrifying portmanteau, Jackson replied: “We finish the story.”

An entire album emerged covering the love triangle saga of the ‘other woman’ and Mr and Mrs Jody. Jody had been the name given to many a wrong-doing lover man, from Johnnie Taylor’s 1970 Stax ’45 ‘Jody’s Got Your Girl And Gone’ to Jackson’s Spring label mate Bobby Newsome on ‘73’s ‘Jody, Come Back And Get Your Shoes’ and beyond (Marvin Sease’s 1994 ‘I’m Mr. Jody’). In real life Jackson claimed she was more often ‘the other woman’ but told The Atlanta in 2014, she “felt the need to give the wife a say-so” on the flipside. “It was about equality. It wasn’t about taking sides… I did it out of fairness.” The two women hinted at a duality within Jackson. A Cancer with Leo rising, she told Detroit Black Journal in 1978 there were two Ms Jacksons, sensitive, sensible Mildred and fiery, shock-seeking Millie.

Caught Up was deep soul, the kind championed by UK critic Dave Godin and anthologised on his four volume Deep Soul Treasures, soul with a heightened emotional intensity, chiselled by tough times and heartache, its visceral lived experience offset by often lush musical settings. Here the R&B grit of Muscle Shoals’ house band, the Swampers was festooned with Mike Lewis’ sweeping arrangements, the sort of embellishments once considered ‘whiteners’ on Etta James’ Chess sides, now fully incorporated into soul’s ever-expanding palette. Lewis’ orchestrations wafted in and out of the songs, gluing them together, accompanying interludes, ‘skits’ dramatisng the action. To borrow a tag line from another disintegrating marriage song cycle, Lou Reed’s Berlin from 1973, Caught Up was ‘a film for the ear’, a musical soap opera sandwiched between Diana Ross’ cinematic peaks, Lady Sings The Blues (1972) and Mahogany (1975).

It was both iconoclastic and steeped in tradition, exploring well-worn tropes and subverting them. The ‘other woman’ had long been a character in popular culture, a misogynist concoction, her existence defined by men in a patriarchal power dynamic. In 1954’s film noir The Other Woman she’s a femme fatale, a malevolent ‘man-eating’ archetype reverberating into he 80s (Fatal Attraction) and beyond. On Jessie Mae Robinson’s song of the same name she was elegant and doomed, a well-preserved exile from domesticity’s supposedly loving lair, sung with increasing solemnity over the years by Sarah Vaughan, Nina Simone and Lana Del Rey, the lonely world that created her seeping in with each successive take. She barely existed on the title track of country singer Ray Price’s 1965 The Other Woman, soothing his ‘wounded pride’, as invisible as the wife in a tale of male self-pity, void of responsibility. Feared, pitied, a mere conduit for male needs.

Then she started speaking for herself.

Doris Duke’s 1970 southern soul classic I’m A Loser, found her unashamed but trapped on ‘To The Other Woman’, closing an album of gutsy determination and tragic resignation. Oscillating between lost love (‘He’s Gone’, ‘Ghost Of Myself)’, marital strife (‘Congratulations Baby’, ‘Divorce Decree’) and addiction (‘I Can’t Do Without You’), Duke’s characters face circumstance with defiant gusto. But they’re stuck inside them, caught up, exploited, duped and sliding into sex work on ‘I Don’t Care Anymore’. This was female protest echoing the mighty Marlena Shaw’s ’69 ‘Woman Of The Ghetto.’ A real precursor to Caught Up, I’m A Loser told a stark, uncompromising truth about women living at the intersection of class, race and sex, apparently unsettling males too. “It was woman’s album. Men found it depressing,” said writer/producer Jerry ‘Swamp Dogg’ Williams Jr.

Irma Thomas, 1973’s In Between Tears, was another Swamp Dogg-produced stepping stone towards Jackson’s masterpiece. The Queen of New Orleans Soul also played spouse (‘She’ll Never Be Your Wife’) and ‘other woman’ (‘These Four Walls’), her total immersion humanising them equally. She revisited her 1964 classic, ‘I Wish Someone Would Care’, a dramatic remake prefaced by a ferocious monologue, ‘Coming From Behind’. Feminist spoken word followed sung despair, striking at a complex tension. The necessity of freedom and equality couldn’t erase the inevitability of human loneliness, complicated emotions Jackson would further explore (see also Joni Mitchell’s 1974 Court And Spark).

Old certainties crumbled in the 70s. Popular song pushed boundaries, chronicling relationships in raw, unflinching detail, from Freda Payne’s 1970 ‘Band Of Gold ‘to The Persuaders’ ‘Thin Line Between Love And Hate’ in 1971. Infidelity became romanticised not demonised in 1972, not just by Luther Ingram but Billy Paul with ‘Me And Mrs Jones’, 45s from an era when marriage and monogamy were decaying pillars of an unravelling status quo.

In this new landscape, the other woman was now just another woman navigating life and loneliness, requiring a better road map than man-made conventional morality. When Black American music was raising consciousness, tackling big issues from Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On to The O’Jay’s ‘Ship Ahoy’ Millie Jackson’s Caught Up knew part of the struggle was happening at home, in the bedroom.

It opened with ‘If Loving You Is Wrong’ and ‘The Rap’, plunging listeners straight into the drama, turning up the heat on Ingram’s original, replacing unapologetic world-weariness with ‘mad love’, something grander and rawer; full throttle orchestration and Jackson’s impassioned delivery (an underrated vocalist, she elicits comparisons with Gladys Knight, Candi Staton, even Teddy Pendergrass). The lyric accepts the other woman’s circumstances, the vocal tears into it, a torrent of devotion, loneliness and frustration, unleashing wild, James Brown-style exclamations. This was female desire a world from Donna Summer’s orgasms on ‘Love To Love You Baby’ a year later. An additional, climactic lyric, “I’ve been loving you too a little bit long”, compresses the regret and defiance into an Otis Redding reference.

‘The Rap’ travels deep inside the woman’s head, assessing the ‘two sides’ good and bad, of being with a married man.’ Midnight hour solitude is offset by sexual satisfaction, liberation from the drudgery of married life, depicted here as an erotic dead zone of chores, washing your husband’s “funky drawers”. But resentment lingers as she takes pot shots at the wife. “These were conversations women were having with each other down the laundromat. You didn’t hear it on record. You especially didn’t hear them on the radio,” Jackson told The Atlanta. Moving through comedy, cruelty, pleasure and desperation, Jackson was telling you not how it should be, but ‘like it was.’

There’s shrewd awareness too, flickering through the intensity, that she’s playing a role, rehearsing “sweet things” to tell her lover when he returns on “J-1” after family time. It’s a subtler echo of the performative femininity aggressively parodied on Betty Davis’ ‘He Was A Big Freak’ that year. Unsurprisingly, Jackson became a drag favourite, revered by RuPaul and performers like Atlanta’s late, legendary Charlie Brown.

The music captured the conflict, skulking in the shadows with her, locked into a snaky, nocturnal, groove, supplied by Jimmy Johnson’s wah-wah, David Hood’s bass, Barry Beckett’s organ, keys tinkling like quietly jangling nerves. Sporadic blasts of brass accompanied testifying passion (“you are my sunshine!”). Caught between shadow and light, the chiaroscuro evoked a secret love’s barely contained tensions. At the climax she hears the clock ticking, evoked by rim-clicks and stuttering horns, counting down not just to her lover’s departure but her own ability to remain the ‘other woman’ (she ignores it).

Less X-rated than its live incarnation, ‘The Rap’ was nonetheless a taboo-busting revelation, showing how the spoken word could deepen a song’s intimacy, both lover and listener are directly addressed, the fourth wall’s broken, dragging it into real life, exploring the messy emotions pop poetry usually neatly contained.

The spoken word had a unique significance in African American life, from the oral tradition preserving an enslaved people’s culture via story telling to the rousing political speeches that galvanised the civil rights movement in the 1960s, to the sermon in the pulpit. Soul had taken talking into mainstream pop, with romantic confessionals like The Supremes’ ‘Love Is Here, And Now You’re Gone’, Aretha Franklin’s 1973 ‘Angel’, or Barry White’s voice-over to his seduction soundtracks. But it became crucial for serious themes; from Marvin Gaye’s ecological prayer ‘Save The Children’ to Gil Scott Heron or The Last Poets’ proto-hip hop street poetry.

Jackson’s lodestar was Isaac Hayes, whose landmark 1969 Hot Buttered Soul had mixed songs and monologues to devastating effect, reworking Jimmy Webb’s ‘By The Time I Get To Phoenix’ into an epic 18-minute melodrama of adultery, break-ups and heartache. She described herself as ‘the female Isaac Hayes’ eventually collaborating with him on 1979’s Royal Rappin’s.

Jackson wasn’t speaking in rhymes but ‘The Rap’ earned her the reputation as ‘the godmother of hip hop’ (Questlove simply dubbed her its creator), its unvarnished, frank reportage predating ‘The Message’ by nearly a decade. She simultaneously articulated female experience and pioneered musical forms, like 1974’s proto-punk ‘Hey Joe’ / ‘Piss Factory’ by Patti Smith, both daring to ‘say the unsayable’. Such provocations were doubly subversive when coming from a black female artist. Named the ‘female Richard Pryor’ for her similarly wicked humour, Jackson claimed the stand-up comic treated her like ‘Satan’ when they shared a stage, indicative of sexist double standards.

On ‘All I Want Is a Fighting Chance’ lover confronted wife to stampeding funky R&B, horns blaring, guns blazing as she declared love for her husband. Ostensibly it pits two women against each other ‘cat fight’-style but subtlety undercuts the soap-operatic. In the introductory skit she describes them as “wives-in-law”, two sides of the same patriarchal coin, later calling herself “the daughter of a son of a gun”, suggesting the relationship dysfunction’s inherited.

After carnage comes reflection, the ‘other woman’ reporting on the day’s messy events to Mr Jody over sweeping strings, leading into Leroy Phillip Mitchell’s ‘I’m Tired Of Hiding’, closing her story and side one. Deep soul introspection finds her refusing to stay in soul music’s former corners of forbidden love, The Corsairs’ 1961 ‘Smoky Places’, James Carr’s ‘The Dark End Of The Street’. Tenderness comes with a hard core, issuing an ultimatum to her married lover. She demands more (“there’s gotta be some changes”), just like Patti Jo’s tough, assertive sensuality on 1973’s ‘Make Me Believe In You’ filling gay disco floors. Neither villain nor victim, it leaves her acknowledging an affair’s emotional toll; soul-searching epiphany rather than moral judgment.

Side two thrust the listener into Mrs Jody’s world. On ‘It’s All Over But The Shouting’, she sends her two-timing husband packing. This tornado of female resistance matches side one’s closer, as well as Irma Thomas’ ‘We Won’t Be In Your Way Anymore’ and Thelma Houston’s ‘You’ve Been Doing Wrong For So Long’, a Grammy-nominee from 1974 that could have come straight from Mrs Jody’s lips. Impervious to her husband appeals, she falters on the subsequent skit where Mr Jody makes his sole appearance, their exchange being scene-setting for another Mitchell composition, ‘It’s Easy Going’. Lyrics catalogue his wrong-doing with clear-eyed sobriety, but the feeling is deep soul regret, a vocal that rises to anguish over an immersive, filmic soundtrack; woodwinds, strings, swirling keys, acoustic guitar. It’s redolent of the era’s romantic cinema where happy endings weren’t guaranteed, oddly anticipating the theme to 1976’s UK adultery melodrama, Bouquet Of Barbed Wire. Pitched somewhere between the future farewell of Gloria Gaynor’s ‘I Will Survive’ and the cri de coeur of Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes’ ‘I Miss You’, it showed Jackson’s knack of conjuring conflicted, complicated adult emotions.

There’s more hard-won emotional wisdom with a reading of Bobby Womack’s ‘I’m Through Trying To Prove My Love To You’, prefaced by a string-soaked interlude and Mrs Jody’s balanced monologue’s, accepting her responsibility, establishing boundaries. Both mature break-up ballad and tear-stained showstopper, it’s full of shattered illusions and sad acceptance. The arrangement’s stunning, Stax horns, grand strings, a synth sobbing lonely teardrops, like the electronics rippling through Ann Peebles’ ‘I Can’t Stand The Rain’ that year. But the breath-taking vocal is centre-stage, displaying Jackson’s ability to fully explore a song’s emotional potential, rivalled only by Gladys Knight, whose 1975 ‘The Way We Were / Try To Remember’ was another master class of gut-wrenching loss, another performance where theatrical flair and pure emotion converge.

For the finale, Bobby Goldsboro’s 1973 hit, ‘Summer (The First Time)’ is transformed from a hazy erotic fantasy of a young man being deflowered by an older woman into a Mrs Jody flashback to being seduced by her much older, future husband as a young virgin. Recalling innocence lost, sung with experience painfully gained, Jackson makes the song flesh and bone, bringing the lyric’s sensual poetry to life (the demon sun, the steaming pavement, the sweat dripping on her gown, almost melting her). This is not the gorgeous, soft-focus 70s nostalgia of Diana Ross’ ‘Touch Me In The Morning’ or Michael Jackson’s ‘One Day In Your Life’, but the bittersweet memories that haunt real life, wistful for lost love, the yearning complicated by unsettling, uneven power dynamics. That rasp in her voice contains more than heartache, there’s real rage there. The arrangement is both suitably hard-edged, hammered ivories and percussion, and reflective, strings swaying lie trees in the breeze of some lost, golden summer.

Some merely sang songs. Millie Jackson lived them.

Caught Up closes with Mrs Jody’s final farewell to her (ex-) husband, a mantra of confidence, clarity and closure: “Now is the time to say goodbye”. Both of Caught Up’s female protagonists break have broken free from the ‘other woman’s constraints, the man who defined the genre is merely an illusory presence here. Each respective side really documented not a woman’s relationship to a man but her journey towards self-determination.

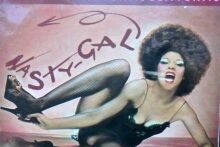

David Wiseltier’s cover art visualised the love triangle in striking, lurid detail, depicting a spider web with the bewildered husband at the centre, flanked by the two female characters. All three are stuck not just in their romantic entanglements, the havoc woven by the human frailty of desire, but the wider world’s trap, of pressure and inequality. Reminiscent of The Seeds’ 1966 sleeve, A Web Of Sound, it also seemed plucked straight from Blaxploitation, filling cinemas, dividing opinion. Pam Grier springs to mind, heroically fighting her way though the creaky plots of a white man, Jack Hill, transcending their confines, radiating a black female power that peaked in 1974 with Foxy Brown.

Spring Records were impressed, but unsure of how to market a ‘concept’ album, turning to WBLS Radio DJ Frankie Crocker for advice. He left with an acetate, began playing ‘If Loving You’ immediately. Caught Up rose to number 21 on the Billboard Hot 100 and made number four in the R&B charts. It resonated with people, striking a deep chord within the lives it dramatised, with Jackson’s fan mail resembling letters to an agony aunt. “I was the poor people’s queen,” she told The Atlanta. “I didn’t sell records to bougies… people in the projects understood me.” Nominated for a Grammy the following year in the Best Female R&B performance category, Aretha took the trophy home, presented by a coked-out Bowie.

But Caught Up was part of female soul explosion. Top tier long players proliferated throughout 1974. Ann Peebles’ luxurious, gritty, modern I Can’t Stand The Rain easily matched Hi label mate Al Green’s efforts. Shirley Brown was ploughing similar terrain to Jackson on Woman To Woman, its title track, one of Stax’s later hits, featuring a spoken word intro, staging a phone call between a wife and her husband’s lover, Barbara (Barbara Mason responded immediately with ‘From His Woman To You’). There was also Gloria Scott’s exquisitely crafted What Am I Gonna Do, produced by Barry White during his purple patch, Scott spinning in reverb-drenched, hazardous ecstasy on the title track’s climax, head wearily in hands on the cover, caught up.

Like Jackson, Betty Davis chafed at respectability politics with They Say I’m Different’sferocious funk, her liberated self-expression incurring the NAACP’s wrath, garnering bomb threats, the transgressive wallop of a female ‘doing what the guys do.’ Closer to the mainstream, Labelle eroded genre boundaries with Nightbirds, featuring ‘Lady Marmalade’ and a rousing call for unity, ‘What Can I Do For You?’, less ‘girl group’, more full female ensemble. Others were speaking a new, bold truth to male power; The Three Degrees (1973’s ‘Dirty Ol’ Man’) and The Pointer Sisters (1975’s ‘How Long’)

It continued into 1975 as disco coalesced (Gloria Gaynor’s Tom Moulton-mixed Never Can Say Goodbye) and Yvonne Fair’s The Bitch Is Black, exuding the same strength and vulnerability as Jackson, heartbroken yet irrepressible on ‘It Should Have Been Me’. By 3 July Labelle would be the first black group to grace Rolling Stone’s cover, the same summer Jackson released her love triangle’s sequel Still Caught Up. Knowing that life is messier than art and the struggle is never over, it’s a sadder record than its predecessor, ignoring all its warnings, the ‘other woman’ committed to a psychiatric ward by the end. She wasn’t there for long though, being Free And In Love by 1976, Feelin’ Bitchy in 1977.

Jackson became known for her mischievous wit and shock value. “Erotic! Explosive! Explicit! Sizzling!” was Mavis Nicholson’s intro for an ITV interview in 1985. The Washington Post dubbed her the “veteran virtuoso of vulgarity”. It was this side of her that blazed a trail for Prince’s porno narratives on Dirty Mind or Madonna’s Erotica. While the latter was undoubtedly a pop innovator, her failure to recently recognise her forebears, specifically woman of colour like Jackson reeks of superstar solipsism. Hip hop divas, from Lil’ Kim to Nicki Minaj, owe her a serious debt too.

But Caught Up derives much of its power not from raw sex, but sensuality and emotional truth. Breaking ground with ‘The Rap’, her singing remains an overlooked asset, like Caught Up’s sophistication. Jackson was concaving concepts before Donna Summer’s Moroder-assisted albums, ones from a real world not a feverish imagination (1974 was the year of Diamond Dogs and The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway), stylishly reinterpreting years before Grace Jones. In an atomised decade where break-ups came thick and fast in popular culture, this was multi-focal soul-baring years before Rumours. Funnier, smarter and more moving than much of the music on that 1974 NME list, Caught Up remains a masterpiece, and Jackson, to quote RuPaul, remains ‘the originator.’