The goal of psychoanalysis, argues Adam Phillips, is to become boring to yourself. It is “the therapy that frees people to lose interest in themselves; there’s nothing more self-preoccupying than a symptom, nothing finally less interesting than one’s self”. Becoming less self-interested may depend on forgetting, but repression isn’t forgetting – it only preserves detested memories for later. True forgetting – freedom from haunting memories – comes only through self-acceptance.

Our surveillance capitalist media landscape, however, hardly lends itself to such forgetting. Since Michael Haneke’s Caché (2005), made in a post-9/11 climate of rampant surveillance, scrutiny of public figures has only intensified, with their most insalubrious moments dominating Google’s top results. Caché centres on Georges Laurent (Daniel Auteuil), a French television talkshow host and the most incurious academic who ever drew breath. Many public figures have a creeping sense of being surveilled, but Georges’ predicament takes the biscuit.

His troubles begin when he receives a videotape: hours of static footage of the exterior of his Parisian house. This image is Caché’s opening establishing shot, but the fact that it’s being watched on TV by Georges and his wife, Anne (Juliet Binoche), is a reveal. Another tape follows, this time accompanied by a childlike drawing of a man bleeding from the head; then another equally disconcerting tape arrives. In the absence of help from the authorities, Georges finds himself led to a dingy apartment on the outskirts of Paris. Despite a growing suspicion he knows who the culprit is, Georges remains infuriatingly tight-lipped, sharing nothing with his increasingly disgruntled wife. For all of the learned books lining the walls of his spacious home, Georges doesn’t understand repression or how its disavowal is shaping his present. Freud believed that the greater the resistance to a memory, “the more extensively (its) repetition replaces remembering”.

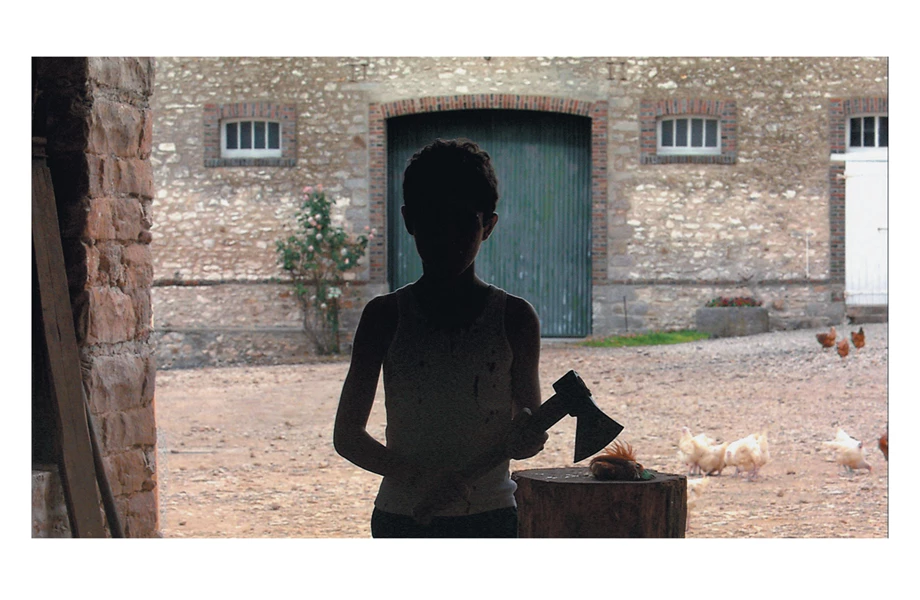

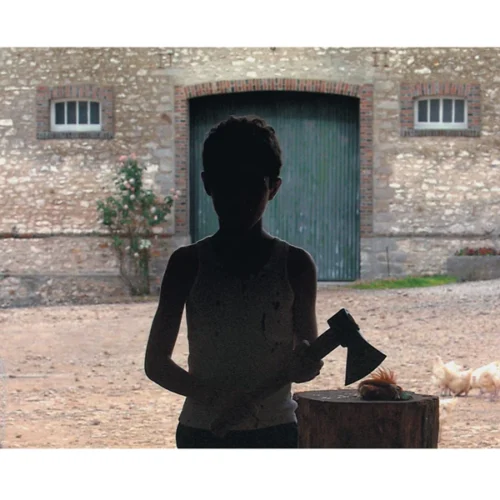

In the apartment, Georges finds Majid (Maurice Bénichou), an Algerian Arab he wronged as a child. Georges’ parents had been in the process of adopting Majid after his own were killed during the police massacre of Algerians on 17 October 1961. Resenting the intrusion, young Georges tricked him into killing a chicken, leading to Majid’s expulsion.

Georges suspects Majid of sending the eerie tapes, but the Algerian man doesn’t seem hostile; he’s remarkably peaceable considering what a decisive role Georges has played in his life. But the next lot of surveillance footage arrives but this time it comes from inside Majid’s apartment, capturing Georges berating him, both unaware of the camera.

On these tapes, the camera’s gaze is unwavering but refuses to fully determine the recipient’s inferences. This unstinting gaze is also a Michael Haneke hallmark. His cinema, rather than cajoling the viewer into a certain emotional state, aspires to the aesthetics of surveillance. His camera, like dispassionate CCTV, tracks both banal and explosive scenes with the same unadorned flatness. With diegetic and non-diegetic music largely absent, this gaze bears witness to inhumanity, more disturbing for its matter-of-factness.

Haneke’s career got off to a typically bleak start with The Seventh Continent (1989), in which a family collectively commits suicide. Throughout his oeuvre, he’s explored the distancing effects of media consumption and how, he claims, this can breed apathy towards (and complicity in) violence. Fans of ultraviolent genre cinema may see this as the tutting of a moralist, but in response, Haneke might point to the recent uptick in live-streamed murder as vindication. He intends to resensitise us to violence. The rather didactic Funny Games (1997, 2007), made twice, impugns our gaze, making us tag along as two fourth-wall-breaking young men pointlessly brutalise a middle-class family. The Piano Teacher (1992) is a troubling portrait of sexual dysfunction and emotional disequilibrium. In Benny’s Video (1992), a boy films himself killing a girl.

The purpose of the tapes in Caché is more confounding. Primed by conventional thrillers, the viewer approaches Caché as if it were the kind of mystery that will have a conventional resolution, the most burning question of course being: who’s sending these tapes? But the answer remains elusive.

One video tape even shows Georges walking past the mysterious cameraperson who is supposedly menacing him; except he doesn’t notice anything – just like characters in most films don’t. The tapes use the same Super 35mm camera as Haneke’s own shots, resulting in diegetic/extra-diegetic collapse. Does this mean our world and the film’s are intermingled? Is Haneke the sender? Or is it us, the viewers, voyeuristically keeping sentinel outside Georges’ house – a reverse fourth-wall break, the opposite of Funny Games?

Or does indeterminacy just reign supreme? Is Caché about our insistence on interpretations, however misplaced? There’s truth in that, but the central mystery remains insoluble by design. Caché’s elisions are structuring absences meant for Georges to project onto.

As Thomas Y. Levin writes, Caché becomes less about the tapes’ sender than what they show. Though tonally realistic, Caché may unfold in psychological space: the videos are extrusions from Georges’ guilty, much-neglected conscience. When you’ve transgressed against the moral order, it can feel like the universe conspires to make you face the person you’ve wronged. Fear of others’ judgement forecloses confession, which also gives credence to the notion that we, the public, are behind the tapes: a silent jury conjured up by Georges’ addled psyche. We’re the internalised surveillant gaze his guilty conscience has wrought. What is the internal critic (the superego) but the imagined judgement of others.

In fact there’s ample evidence the tapes spring from Georges’s unconscious. One video shows a hallway in Majid’s apartment complex. In the following scene, an establishing exterior shot outside Majid’s apartment complex is revealed as Georges’ perspective from a cafe across the street. We then see the hallway outside Majid’s apartment, a shot identical to the one on the tape, until Georges himself walks into the frame. Georges assumes the surveillant perspective from the tapes. “‘The unknown ‘agency’ of the early tapes”, as Levin writes, “is now recast as the externalised workings of Georges’ bad conscience (think: return of the repressed).”

Georges’ paranoia, his sense of being surveilled, transforms him into a surveillant accuser. Later, he dreams of when Majid was forcibly removed from his family, and the POV resembles the film’s surreptitiously shot opening scene. The overlaid sound of chirping birds is the same. Aesthetically, the tapes, Georges’ dreams, and his POV in staking out Majid’s apartment are all of a piece. The greater the repression, the harder the unconscious presses to reveal what the conscious mind refuses. The unconscious seeks revelation not to punish but to heal.

Yet, it’s not uncommon for the unreflective to feel hostility towards those that they have wronged. Georges finds it easier to believe that someone is out to get him than to admit there’s incongruity between his conscious life and his unconscious. This evokes the meme: Men will literally [insert activity] instead of going to therapy.

Though the viewer may be tempted to judge Georges harshly, he was only a child when he committed his fateful sin. Still, working on yourself reveals an uneasy truth: you’re not responsible for what happened to you as a child, but you are for how you face the repercussions in adulthood.

Zooming out from the micro to the macro, such avoidance can be compared to that of the citizen who dehistoricises their place in a nation’s blood-soaked legacy – these were our forefathers’ sins, nothing to do with me. Comparisons with such disavowals are apposite, as Majid is an Algerian Arab. Eventually, after so long spent clamming up, Georges finally unclams, admitting to Anne how he hurt Majid, and in doing so mentions the Paris Massacre of 17 October 1961, when scores of peaceful Algerian anti-war protesters were murdered in cold blood by the French National Police. Just like Georges’ transgression, these crimes remain undigested – ignored yet quietly unsettling, a whisper on the wind.

Unprocessed guilt isn’t the only thing that can potentially curdle the mind; parenthood can also make people reactionary. The idea that the brood must be protected can override everything else. Ironically, the parental urge to protect children – often regarded as one of the main planks of adult responsibility – can, in some, engender a xenophobic mindset that is itself infantile. It’s fitting then that Georges’ enmity for Majid, even though it is an allegory of wider political realities, began with a child’s refusal to share. As T. Jefferson Kline notes in an essay, “Georges has used the appearance of the set of ‘terrorist’ videos to get back at an enemy from his childhood, whose sole crime was to have encroached on Georges’s personal sense of his home(land).”

Such knee-jerk othering of Arabs is still alive and well. Breaking news video footage of atrocities attract comments on social media such as “the religion of peace strikes again”, often before any exact culprit has been identified.

Georges’ othering of Majid is more subtle though. Initially at least, there’s enough to suggest his suspicions are worthy of corroboration. However, as soon as there’s a perceived threat against his family, he becomes atavistic.

Cinema can be an empathy enhancer, but it also makes highhanded judges of us. Like Georges, viewers grow cocksure in their assumptions, blind to their projections. We’re initially complicit in Georges’ belief that Majid is the perpetrator of his harassment; when we realise he’s mistaken, we judge Georges instead. Viewers aren’t so different from Georges staking out Majid’s home: this mediocre man embodies our complacent passivity, the averted eye sustaining society’s inequities.

Freud believed the past events are bound to repeat when repression keeps them from coming to light. So after Pierrot (Lester Makedonsky), Georges’ son, goes missing, Georges has Majid carted off all over again – while also echoing the hundreds of Algerians detained on 17 October 1961 (and foreshadowing ICE’s current detentions American citizens).

Georges is starved of the truth about his own psyche. Unsympathetic though he is, the chronically repressed deserve pity – a repressed person is an organism out of whack with its reality. After all, it’s likely that we’ve all been there. Buddhism teaches that resisting reality causes misery (dukkha). Psychological health hinges on accepting past failings: by accepting the feared object, the mind stops wasting energy on evasion. Perhaps the “terrorist” tapes even serve a positive purpose.

Georges’ eventual confession to Anne is progress of a sort, but in Haneke’s films catharsis is a luxury reserved for the bourgeoisie. Majid’s suffering will never be recognised. His shocking suicide before Georges typifies the despair of the oppressed when society refuses to acknowledge their plight. Just as repression destabilises the psyche, the suppression of the oppressed renders society dysfunctional.

Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind (2004, Michel Gondry) explores the emancipatory potential of forgetting, only to caution against obliterating the past. The protagonist Joel undergoes a procedure to forget his relationship with ex Clementine, but when they ultimately meet again, they fall for each other anew, destined to repeat their tortured romance. Clementine warns they’ll annoy each other. As Todd McGowan writes, Joel poignantly accepts this inevitable struggle, surrendering to the inescapable antagonism relationships demand. Long-term intimacy is hard-won, requiring endurance of irreconcilabilities – a generosity often reserved for lovers or friends but withheld from outsiders, as the relationship between Georges and Majid shows.

While the impulse to forget is understandable, it can be a godless affront when it eradicates the lived experience of those wronged. The erasure of memory also strips someone of their personhood, as shown in Haneke’s Amour (2012),which concerns the deterioration of a woman with dementia. His previous film, The White Ribbon (2009), traces the roots of authoritarianism in Germany, where justice for the mistreated at the local level is eclipsed by the wider exigencies of World War I – repression that will see the village’s abused children grow into Nazis.

But forgetting is one thing; screening out what’s before your eyes is another. Critics noticed that Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone Of Interest was reminiscent of Haneke – with its surveillance camera-like setup and demurrals from depicting outright violence or overdetermining the viewer’s experience. The film follows the idyllic, quotidian life of Nazi commandant Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel) and his family, who live next door to Auschwitz. With the cries of Jewish prisoners audible, unconscious defences are no longer sturdy enough. Rather than repression (involuntary), their proximity demands suppression (voluntary), which is more of a struggle – as demonstrated by the harried sleeplessness of Hedwig Höss’s (Sandra Hüller) mother, who, after a visit, slips away without saying goodbye.

In the climactic scene, newly tasked with transporting 700,000 Hungarian Jews to their deaths, Rudolf Höss retches – a moment indebted to The Act Of Killing – before a flash forward to the present time, and a scene which shows janitors cleaning the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. This bold move, as A.A. Dowd writes, points to how this compartmentalisation is as much a problem for us now as it is historical.

How apt that while accepting the Oscar for Best International Feature, Glazer stated, “We stand here as men who refute their Jewishness and the Holocaust being hijacked by an occupation which has led to conflict for so many innocent people.” This took immense bravery amid the shameful hush over the ongoing decimation and displacement of Palestinians.

It was ever thus. In Caché, while Anne and Georges discuss Pierrot’s disappearance, their television shows Palestinians carrying bloodied bodies through the streets. To them, the Palestinians are ignorable sufferers, an ambient background presence, just like the Algerians had been to most French. Except, nowadays, ignoring the starving and the displaced on our newsfeeds requires a concerted suppression not unlike that summoned by the Höss family.

Can alliances form across such gulfs? Perhaps Caché’s final lingering shot outside Pierrot’s school hints at cautious hope. Among the kids milling around, Pierrot and Majid’s son talk amicably, as if willing to accept the antagonisms their parents could not. As Carl Jung wrote, “The greatest burden a child must bear is the unlived life of its parents.” Could these youths be breaking the curse of obfuscation, both personal and political?

But this is Haneke. Isn’t a bleaker outcome more likely? Maybe Majid’s son is exacting revenge through Pierrot. Such a leap, drawn from wholly inconclusive footage, only implicates the viewer further, proving perhaps that those who have this thought have learnt nothing from Georges’s accusatory floundering. Haneke has lured viewers into reflexive prejudice again. Majid’s son just stated earlier that he wasn’t motivated by bloodlust. This surveillant perspective is at an open-ended remove, so the viewer rushes to interpret it like hasty commentators underneath a decontextualised video on social media. In such circumstances, the viewer reveals more about themself than the film. Haneke, modest about what he – or his viewers – can truly know, withholds solutions, preserving the unknowability at the heart of reality. His surveillant filmmaking doesn’t editorialise, reminding how often media dictates to its users.

As Kevin Stoehr writes, Haneke’s ultimate vision is one of perspectivism: the notion that truth is bound to myriad, often conflicting perspectives and can’t transcend it. So viewers snatch at their own takeaways as if presented with a Rorschach ink blot test; Haneke likely has his; Pierrot and Majid’s son hash out something that will remain unknown. Access to their reality is circumscribed by the mindset of the viewer. Haneke’s filmmaking looks at people empirically, honouring their irreducible dissimilarities. The artist can hold the antagonisms when people cannot. Grim though his vision is, there’s something salutary in his faithful rendering of the humans behind these failures of communication.

Haneke’s clinical bleakness is not in service of chilly nihilism but a wounded humanism: rather than looking away, he holds conflicting perspectives in suspension. Encounters with hate and violence tend to shrink a person’s perspective; with Haneke, both his and the viewers are expanded.